Tweet by Anthony Ryan (@printtemps), Dec. 9.

From Thomas Piketty: A Project to Save Europe . . . and the Climate

The following statement was published today in The Guardian under the headline, Our Manifesto to Save Europe from Itself, under the signature of Thomas Piketty, the French economist who rose to global renown with the 2013 publication of his scholarly work, Capital in the Twenty-First Century.

The statement, co-signed by over one hundred European economists, outlines a plan to revitalize the European Union with with a “new, sovereign European assembly capable of producing a set of fundamental public goods and services in the framework of a lasting and solidarity-based economy,” paid for by a suite of “four major [new] European taxes” including a carbon tax set at a minimum of 30 euros per metric ton (equivalent to around $31 per U.S. short ton).

While the proposal presumably was provoked by the ongoing “Gilets Jaunes” protests rocking France, its ambitions are far greater than simply responding to the current unrest. We are of course encouraged that the proposed program includes a carbon tax.

We are grateful to the editors of The Guardian for publishing the manifesto in full. The original version on The Guardian’s site includes a complete list of signatories. We have changed European syntax in some places to American style and have bolded passages deserving emphasis.

— Carbon Tax Center

Since the election of anti-European governments across the EU, and with Brexit looming, it is no longer possible to continue as before. We cannot simply wait for the next departures, or further dismantling without making fundamental changes to present-day Europe.

Our continent is caught between political movements whose program is confined to hunting down foreigners and refugees, on one hand, and on the other those who claim to be European but in reality continue to consider that hardcore liberalism and the spread of competition are enough to define a political project. They don’t recognize that this lack of social ambition is what leads to feelings of abandonment.

French “Gilets Jaunes” protesters in Paris Saturday, Dec 8.

There are some movements attempting to end this fatal dialogue and address the structural problems that have arisen after a decade of economic crisis. There is no lack of these specifically European-critical situations: structural under-investment in the public sector, particularly in training and research, a rise in social inequality, acceleration of global warming and a crisis in the reception of migrants and refugees. But these movements often have difficulty in formulating a coherent alternative project, and in describing precisely how they would like to organize the Europe of the future.

This is why we, European citizens from different backgrounds and countries, are today launching this appeal for the in-depth transformation of the European institutions and policies.

Our manifesto contains concrete proposals, in particular a project for a democratization treaty and a budget project – and we have made it all publicly available. Our ideas may not be perfect, but they do have the merit of existing. The public can access them and improve them.

They are based on a simple conviction: Europe must build a new model to ensure the fair and lasting social development of its citizens. The only way to persuade them is to abandon vague and theoretical promises.

If Europe wants to restore solidarity with its citizens it can only do so by providing concrete evidence that it is capable of establishing cooperation and by making those who have gained from globalization contribute to the financing of public-sector good. That will mean making large firms contribute more than small and medium businesses, and the richest taxpayers paying more than poorer taxpayers. This is not the case today.

Our proposals are based on the creation of a budget for democratization that would be debated and voted on by a new, sovereign European assembly. This will at last enable Europe to equip itself with a public institution capable of dealing with crises in Europe immediately and of producing a set of fundamental public goods and services in the framework of a lasting and solidarity-based economy. The promise made at the treaty of Rome of “harmonization of living and working conditions” will finally become meaningful.

This budget, if the European assembly so desires, will be financed by four major European taxes, the tangible markers of this European solidarity. These will apply to the profits of major firms, the top incomes (over €200,000 a year), the highest wealth owners (over €1m ) and carbon emissions (with a minimum price of €30 a tonne).

If it is fixed at 4% of GDP, as we propose, this budget could finance research, training and the European universities, an ambitious investment program to transform our model of economic growth, the financing of the reception and integration of migrants, and the support of those involved in carrying out this transformation. It could also give some budgetary leeway to member states to reduce the regressive taxation that weighs on salaries or consumption.

The issue here is not one of creating a transfer of payments across Europe – taking money from the “virtuous” countries to give it to those that are less so. The project limits the gap between expenditure deducted and income paid by a country to a threshold of 0.1% of its GDP – this could only be increased should there be consensus to do so.

This threshold can be raised in case there is a consensus to do so, but the issue is primarily of reducing the inequality within countries, not between them, and of investing in the future of all Europeans. But those calculations would exclude spending that benefits all countries equally, such as action on climate change. Because it will finance European public goods benefiting all countries, the budget for democratization will de facto also foster convergence between countries.

Because we must act quickly but we must also get Europe out of the present technocratic impasse, we propose the creation of a European assembly. This will enable these new European taxes to be debated and voted as also the budget for democratization. This European assembly can be created without changing existing European treaties.

The assembly would, of course, have to communicate with the present decision-making institutions (in particular the Eurogroup in which the ministers for finance in the eurozone meet informally every month). But, in cases of disagreement, the assembly would have the final word. If not, its capacity to be a locus for a new transnational political space where parties, social movements and NGOs would finally be able to express themselves would be compromised.

Equally its actual effectiveness, since the issue is one of finally extricating Europe from the eternal inertia of intergovernmental negotiations, would be at stake. We should bear in mind that the rule of fiscal unanimity in force in the European Union has for years blocked the adoption of any European tax and sustains the eternal evasion into fiscal dumping by the rich and most mobile, a practice which continues to this day despite all the speeches. This will go on if other decision-making rules are not set up.

Given that a newly created European assembly would have the ability to adopt taxes and to affect the very core of the democratic, fiscal and social compacts of states, national and European parliamentarians must be central. This is why we propose, in the democratization treaty available online, that 80% of the members of the European assembly should be from national parliaments, with 20% from the present European parliament.

This choice merits further discussion. In particular, our project could also function with a lower proportion of national parliamentarians (for instance, 50%). But in our opinion an excessive reduction of this proportion might detract from the legitimacy of the European assembly in involving all European citizens in the direction of a new social and fiscal pact, and conflicts of democratic legitimacy between national and European elections could rapidly undermine the project.

Thus national elections will de facto be transformed into European elections. National elected members will no longer be able to simply shift responsibility on to Brussels and will have no other option than to explain to voters the projects and budgets they intend to defend in the European assembly. By bringing together the national and European parliamentarians in one single assembly, habits of co-governance will be created which at the moment only exist between heads of state and ministers of finance.

We now have to act quickly. While it would be preferable for all EU countries to join the project without delay – especially the four largest countries in the eurozone (which represent more than 70% of the GNP and population) – it is designed so that it can be adopted and implemented by any set of countries that wish to do so. It enables those who wish to make immediate progress by adopting this project to do so right now.

We must all assume our responsibilities to participate in a detailed and constructive discussion on the future of Europe, lest our continent is left to sink further into damaging division.

Thomas Piketty is professor of economics at the Paris School of Economics.

Other signatories: Sébastien Adalid, Michel Aglietta, Nacho Alvarez, Julie Bailleux, Marija Bartl, Marie-Layre Basilien-Gainche, Myriam Benlolo Carabot, Loïc Blondiaux, Karolina Borońska, Andreas Botsch, Patrick Boucheron, Emmanuel Bouju, Begnina Boza-Kiss, Hauke Brunkhorst, Bojan Bugarič, Klaus Busch, Julia Cagé, Lucas Chancel, Christophe Charle, Christian Chavagneux, Amandine Crespy, Fabio De Masi, Anne-Laure Delatte, Donatella Della Porta, Yves Deloye, Paul Dermine, Brigitte Dormont, Guillaume Duval, Susanne Elsen, Emanuele Ferragina, Bastien François, Philippe Frémeaux, Diane Fromage, Miguel Gotor, Julien Grenet, Ulrike Guérot, Gabor Halmai, Pierre-Cyrille Hautcoeur, Stéphanie Hennette, Rudolf Hickel, Mario Hübler, Élise Huillery, Simon Ilse, Liora Israel, Michael Jacobs, Yannick Jadot, Luis Jimena Quesada, Christian Joerges, Kädtler Jürgen, Iphigénie Kamtsidou, Jakob Kapeller, Pascale Laborier, Justine Lacroix, Sylvie Lambert, Camille Landais, Sandra Laugier, Rémi Lefebvre, Steffen Lehndorff, Nicolas Leron, Ulrike Liebert, Pascal Lokiec, Philippe Maddalon, Mikael Madsen, Paul Magnette, Maria Malatesta, Francesco Martucci, Frédérique Matonti, Dominique Meda, Robert Menasse, Sophie Meunier, Zoltan Miklosi, Eric Millard, Robert Misik, Éric Monnet, Alberto Montero, Daniel Mouchard, Ulrich Mückenberger, Jan-Wener Muller, Olivier Nay, Sighard Neckel, Fernanda Nicola, Silke Ötsch, Walter Ötsch, Bruno Palier, Mazarine Pingeot, Martin Pigeon, Sébastien Platon, Thomas Porcher, Christophe Prochasson, Thomas Ribemont, Julie Ringelheim, Daniel Roche, Pierre Rosanvallon, Ruth Rubio Marin, Guillaume Sacriste, Emmanuel Saez, Gisele Sapiro, Francesco Saraceno, Thomas Sauer, Patrick Savidan, Frédéric Sawicki, Axel Schäffer, Alan Scott, Thomas Sterner,Julien Talpin, Stéphane Troussel, Laurence Tubiana, Boris Vallaud, Fernando Vasquez, Antoine Vauchez, Brigitte Young, and Gabriel Zucman

I would have been tickled to see success in Washington state, but I never believed an idea this nuanced would survive the last three weeks of the ad wars.”

Massachusetts state Sen. Michael Barrett (D), author of legislation that would establish a state carbon tax, commenting on the defeat of I-1631 in Washington state, in

Carbon advocates won’t quit after a string of defeats, by Ben Storrow, E&E News, Nov. 13.

What killed Washington state’s latest carbon-tax try?

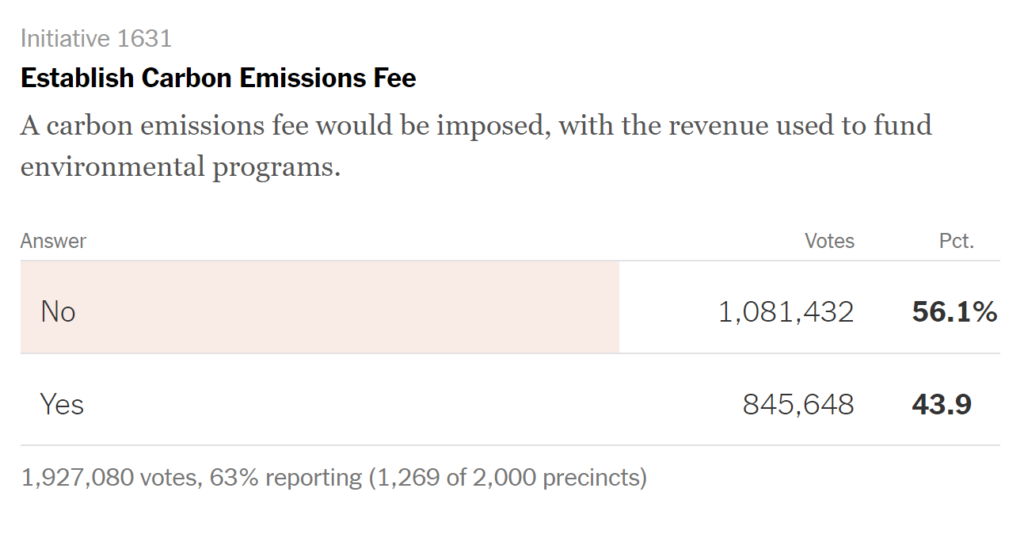

Washington state’s second shot at a carbon tax referendum, I-1631, went down to defeat on Tuesday. The 13-point margin was smaller than the 19-point loss for the 2016 carbon tax referendum, but not much.

That initiative, I-732, was mounted by a ragtag group of carbon tax acolytes from across the political spectrum, led by charismatic but, to some, polarizing economist Yoram Bauman. I-1631, in contrast, enjoyed active support from elements of organized labor as well as the state’s popular governor, Jay Inslee, whose effort earlier this year to push his own carbon tax bill through the legislature fell one or two votes short. I-1631 was also backed by climate-justice organizations and other “left greens” who two years ago opposed I-732, claiming it was insufficiently inclusive and progressive.

Screenshot from The New York Times, Nov. 10.

What happened? How come the supposedly broader base of support for this year’s initiative didn’t translate into a close contest, if not a win?

Of course, fossil-fuel money played a role. The latest figures we saw had the anti’s spending $25 million, much of it from British Petroleum, which operates a large oil refinery at Cherry Point in the state’s northwest corner. But the pro forces weren’t completely outgunned, with $12.5 million raised from the likes of Michael Bloomberg, Bill Gates and The Nature Conservancy.

Those figures don’t include the campaign’s final two weeks, when another wave of Big Oil money almost certainly washed ashore. But it feels simplistic to pin I-1631’s poor outcome entirely on the spending gap.

We don’t yet have a good feel for what happened. But maybe assigning the lion’s share of the carbon revenues to unspecified programs to help deliver clean energy and power savings to low-income households, communities of color and indigenous peoples, as I-1631 would have done, was less appealing to voters than to the constituencies who wrote that language into the initiative.

Maybe some voters figured out that, good intentions aside, I-1631’s revenue allocation might not have sheltered them from the higher energy prices resulting from the carbon tax. After all, the weatherization, better transit and community solar that the revenues were intended to pay for, while eminently worthwhile policies in other contexts, wouldn’t necessarily have offset farmers’ and long-distance commuters’ higher gasoline and diesel costs.

And maybe, just maybe, if leading left greens hadn’t savaged I-732 in 2016 and slandered its sales-tax cuts — which were expressly designed to offset the carbon tax burden on poor and middle-class households — as “tax cuts for corporations” (Heather McGhee, president, Demos) and a burden “on the backs of the poor” (Mary Kay Henry, president, Service Employees International Union), that referendum might have had a fighting chance.

(And let’s not forget Left Green shero Naomi Klein, who slammed I-732 at the last minute with gems like, “[If I-732] is approved by voters, it would be a disastrous precedent that could set back the climate justice movement for a decade — time that we simply can’t afford to lose.”)

Note Klein’s reference to the “climate justice movement” rather than the “climate movement.” Any analysis of the fate of I-1631 needs to look back at the internecine warfare two years ago over I-732 that pitted one against the other.

Meanwhile, economist Tyler Cowen has a thoughtful piece in Bloomberg, The Carbon Tax Is Dead, Long Live the Carbon Tax, with the intriguing sub-head: Maybe its failure on the ballot in Washington state will inspire economists to come up with better arguments. Here’s his gist:

I don’t view the unpopularity of the carbon tax as merely reflecting the influence of special interests. The American people apparently feel that government ought to be able to solve this problem without imposing a new tax burden on them. For all the talk about disillusionment and cynicism in American politics, this view represents a strange kind of optimism. If this issue really is so important, some voters must be thinking, surely you politicians can find a way to solve it without making us pay for everything. Don’t we give you enough money already? There is something admirable about this attitude, even if it doesn’t apply best to this particular case. (emphasis added)

Other reading: David Roberts’ post-election quickie, Fossil fuel money crushed clean energy ballot initiatives across the country, lacks his usual nuance, but is worth reading nonetheless. For local content, there’s this anodyne statement from Carbon Washington, who organized I-732 and campaigned strongly for I-1631, Despite I-1631 vote, Washingtonians still demand action on climate.

Check back here in the next few days. We put this post up quickly and may add to it.

Goodbye to the Climate Solutions Caucus?

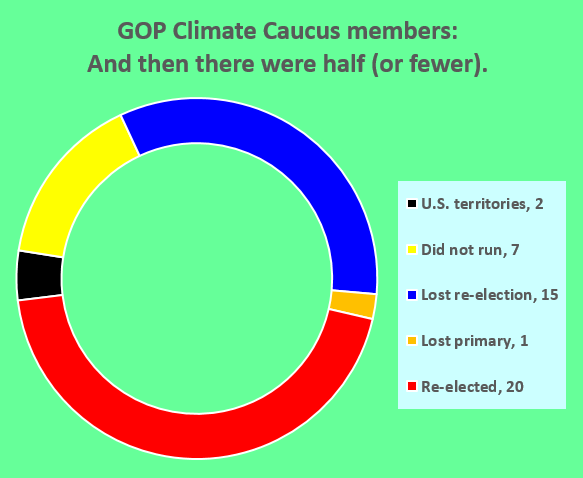

Did any group of incumbent politicians fare as badly in yesterday’s midterms as the Republican members of the Climate Solutions Caucus? That seems unlikely, given the staggering dimensions of the electoral debacle inflicted on them (all figures apply only to the Congressional group’s Republican members):

- 15 members lost their re-election bids (includes cliffhanger defeats of GOP incumbents Mia Love (UT-04) and Tom MacArthur (NJ-3)).

- That’s out of 35 members who were seeking re-election (another 7 stood down, 1 lost his GOP primary, and we exclude 2 members from U.S. territories).

- The loss rate for caucus members — 43 percent — wildly exceeds the roughly 10-15 percent loss rate for Republican House incumbents overall.*

- Caucus members accounted for around half of GOP incumbents’ House losses. (That total, still hard to pin down, appears to be around thirty.)

- With the 15 losses and 8 retirements, the 43-member Republican half of the caucus will dwindle in January to well under half, 20.

[* = Calculating the overall GOP incumbent loss rate isn’t simple, since it requires separating Republicans who stood down from those who ran and lost on Nov 6. District-specific results posted by the Cook Political Report by David Wasserman and Ally Flinn may help. Ditto, Ballotpedia.]

One of the defeated Congressmembers was caucus co-founder and spearhead Carlos Curbelo (FL-26), who was edged out by Democrat Debbie Mucarsel-Powell, a political newcomer.

Meanwhile, “No Democratic members of the climate caucus lost their reelection bids,” ThinkProgress reported, “although two Democratic members are retiring and one is running for a higher office.”

It is true that Republican caucus members on the whole were more vulnerable than other Republican incumbents, for two separate if complementary reasons. One, deep-red districts where climate concern is relatively low tend to be harder for Democrats to wrest from Republicans. Two, some Republicans whose electoral standing was shaky to begin with saw the caucus as a way to bolster their campaigns. For an effective price of zero, these members could signal their independence from Republican denialism and thus burnish their appeal to Democrats and so-called Independents.

It is true that Republican caucus members on the whole were more vulnerable than other Republican incumbents, for two separate if complementary reasons. One, deep-red districts where climate concern is relatively low tend to be harder for Democrats to wrest from Republicans. Two, some Republicans whose electoral standing was shaky to begin with saw the caucus as a way to bolster their campaigns. For an effective price of zero, these members could signal their independence from Republican denialism and thus burnish their appeal to Democrats and so-called Independents.

These points aren’t new to readers of this blog. We first conveyed our skepticism of caucus sincerity in June, with a post, Another Carbon-Dividend Group. Will It Matter?, and followed that a month later with Last Chance to Believe In a Republican-Assisted Carbon Tax? As the midterms approached and GOP incumbents lashed themselves ever tighter to the White House denialist-in-chief, we let loose with the more cynical, “Climate Caucus” greenwashing in full force as midterms approach, in September.

In between, we gave caucus co-founder Curbelo his props with Unicorn or Harbinger? A Republican Carbon Tax Is Readied for Debut. We concluded by remarking that with Curbelo’s introduction in July of a carbon tax bill, a GOP first:

A “long national nightmare” of Republican silence and inaction on climate may be starting to end. Whether other G.O.P. lawmakers will stand with Curbelo remains to be seen. He is at least blazing a path, and for that he deserves our thanks.

Alas, Curbelo’s path was never more than a faint trail. The current Republican Party — which a year-and-a-half ago we labeled “a racket to restore patriarchy, extractionism and white supremacy” — wasn’t about to forsake Trump and the Koch Brothers and coal barons for a “unicorn” Republican Congressmember.

Whither the Climate Solutions Caucus, leaderless and downsized by half? (The disappearance of 22 caucus R’s means that 22 D’s will have to leave as well, to conform to its “Noah’s Ark” makeup whereby each Democrat requires a Republican counterpart, lest the caucus’s vaunted “bipartisan” brand be diluted.)

We expect the caucus will disappear. Not just because its membership is being cut in half but because its uselessness has been fully laid bare. In today’s tribal politics, national-level Republicans can’t evince climate concern except as a token gesture, if that. They certainly can’t act on it by, say, renouncing Trump’s renunciation of the Paris climate agreement, or calling for a national carbon tax or fee. Heresy of that sort guarantees being cast out of the party’s belly and into the political wilderness.

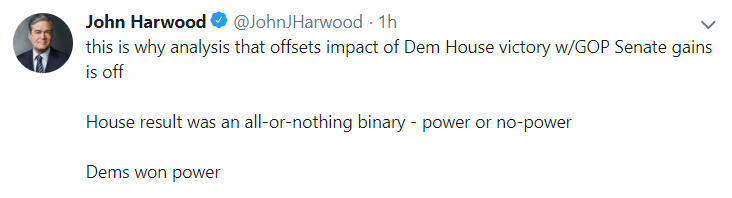

Shed a tear, then, for Carlos Curbelo, but only briefly. The Democratic takeover of the House is worth an eternity of Republican caucus members’ feints, signalings or even token bills. As CNN’s John Harwood tweeted today, the House vote “was an all-or-nothing binary — power or no power. [The] Dem[ocrat]s won power.”

Shed a tear, then, for Carlos Curbelo, but only briefly. The Democratic takeover of the House is worth an eternity of Republican caucus members’ feints, signalings or even token bills. As CNN’s John Harwood tweeted today, the House vote “was an all-or-nothing binary — power or no power. [The] Dem[ocrat]s won power.”

One result: There will be fact-finding congressional hearings, on issues from Russia to climate. If we push hard enough, these will include examination of carbon taxing. Climate activists everywhere — in the U.S. and around the world — will be heartened and emboldened to demand and win real climate action, not lip service.

May 2020 addendum: Click here for Citizens Climate Lobby’s current list of Climate Solutions Caucus members. The same list but with photos is available on the Web site of CSC Democratic member Rep. Ted Deutch.

Canada Unveils Carbon Dividend Plan to Cut Emissions 10% by 2022

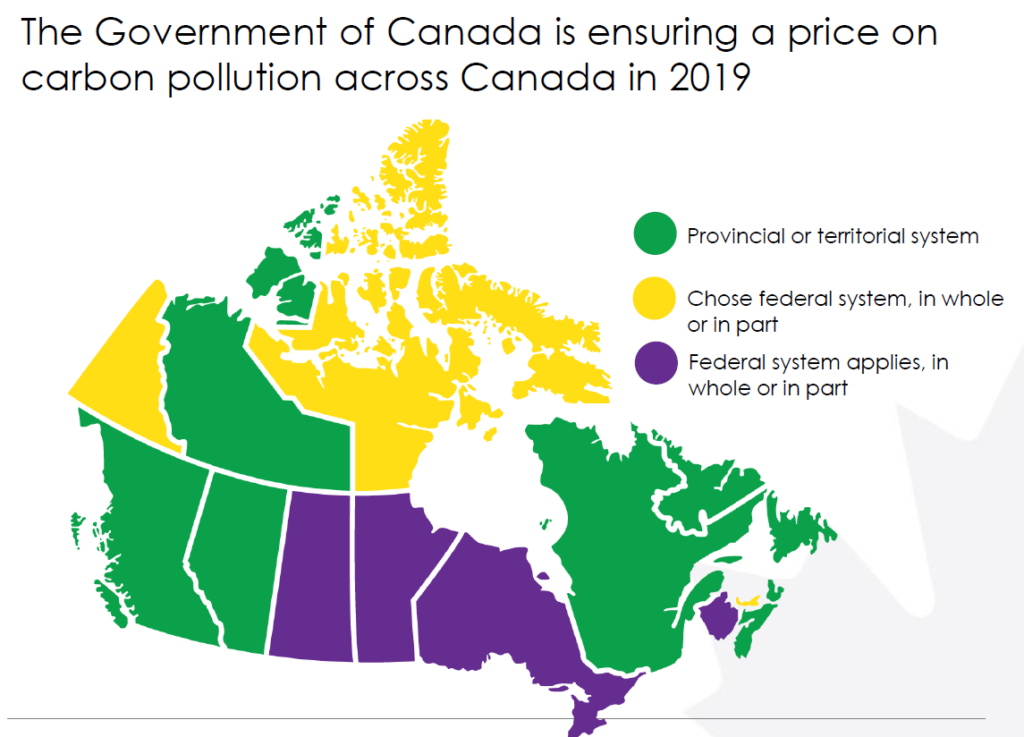

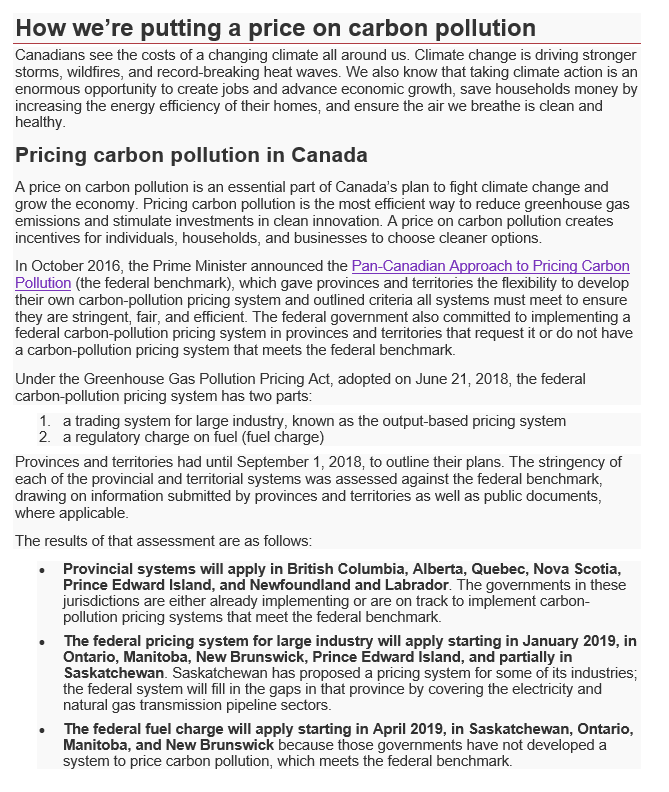

This post from Oct. 24 was amended on Oct. 25 to add the map and reference to David Roberts’ Vox post on the Trudeau carbon pricing plan.

The government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau yesterday announced a national carbon pricing plan that it hopes will yield annual CO2 emissions cuts of 50 to 60 million metric tons by 2022, around a 10 percent drop from Canada’s current emissions.

The plan employs a national carbon price benchmark of $20 (Canadian) per metric ton beginning next year, rising by $10/tonne per year to reach $50 in 2022, according to tables published by the Canadian Department of Finance. Factoring in the 9.3 percent lesser weight of a short ton vis-a-vis a metric ton and the 23 percent lesser value of a Canadian dollar vs. a U.S. dollar, the price trajectory in U.S. terms is $14 per (short) ton, rising by $7/ton per year to reach $35 in 2022.

Map from Canada’s Ministry of Environment & Climate Change outlines Ottawa’s three-prong approach to bring all provinces within a common carbon price.

Perhaps the most innovative element of the plan is the “return” of virtually all of the carbon revenues as dividends to households rather than using the monies to pay for tax swaps or green investments. The plan thus embodies the fee-and-dividend idea long espoused by Citizens Climate Lobby and more recently re-branded as carbon dividends by the Climate Leadership Council, the group fronted by retired Republican officials James A. Baker III and George Shultz.

Ottawa’s dividends proposal includes these provisions:

- The dividends, called “climate action incentive payments,” will be provided annually to federal-taxpaying households by the Canada Revenue Agency.

- Residents of small communities and rural areas get a 10 per cent revenue supplement “in recognition of their specific needs” — presumably, higher fuel needs for heating and driving.

- The dividend amounts will vary by province, presumably with individuals and families of high-carbon provinces receiving larger payments.

“Canada needs to cut its greenhouse gas emissions, and the best way to do that is to put a price on carbon pollution,” declared the country’s Department of Finance in a statement yesterday. “Experts, including Nobel Prize winning economists, have made it clear that pollution pricing is the most effective and efficient way to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions that are giving rise to climate change,” said the statement, which added:

Carbon pollution is not free. Canadians see its effects when extreme weather threatens their safety, their health, their communities, and their livelihoods. They pay for it in the form of structural repairs and higher insurance premiums, food prices, health care costs and emergency services. Climate change is expected to cost Canada’s economy $5 billion annually by 2020.

Several Canadian provinces have already implemented carbon pollution pricing, via a tax (British Columbia) or permit systems via cap-and-trade (Quebec, Ontario, most of the Maritime provinces). The fuel levies published this week by the Trudeau government will now undergo a consultation process expected to last at least several months.

Yesterday’s Finance Dept release includes these three “quick facts”:

- Carbon pollution pricing is the most effective and efficient way to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions associated with climate change.

- Carbon pollution pricing delivers economic benefits because it encourages Canadians and businesses to innovate, and to invest in clean technologies and long-term growth opportunities that will position Canada for success in a cleaner and greener global economy.

- Once in place, carbon pollution pricing could cut Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions by 50 to 60 million tonnes [metric tons] in 2022.

Screenshot from Dept of Finance materials released yesterday as part of Canada’s carbon price policy rollout. Link is at bottom of post.

Total Canadian CO2 emissions from burning fossil fuels were estimated at 549 million tonnes in 2015, according to an international listing compiled by the Union of Concerned Scientists. Assuming the targeted reductions in the last bullet point above are all CO2, the 50-60 million tonne reduction would amount to 10 percent of those emissions. (U.S. 2015 emissions were estimated at 4,998 million tonnes in the UCS listing, though our figure for that year was 2 percent greater.)

By 2022, annual carbon revenues under the plan could be as much as $27 billion (Canadian) or $21 billion (U.S.), although exemptions for trade-exposed energy-intensive sectors and for aviation fuel used in indigenous communities might reduce those figures.

The plan is a daring gambit for PM Trudeau, as David Roberts of Vox explained in a post today, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is betting his reelection on a carbon tax.

The Canadian government’s embrace of household dividends could also provide a shot in the arm for dividends advocates in the U.S., whose credibility has faltered as Congressional Republicans have disdained the supposedly GOP-friendly dividends approach. This morning, Thomas Friedman, a leading champion of bipartisan climate action among U.S. pundits, called on readers of his New York Times column to “vote for a Democrat, canvass for a Democrat, raise money for a Democrat, drive someone else to a voting station to vote for a Democrat” in the midterm elections.

Echoing Friedman’s call, a constituent of Rep. Carlos Curbelo, the Republican Congressmember who broke ranks with his party in July by introducing a carbon-fee-and-dividend bill, told a Times reporter that Curbelo’s climate concern wasn’t enough to win his vote on Nov. 6: “He is unable to overcome the extreme wing of his party. We need to change the team.”

For more information on Canada’s carbon-pricing plan:

- Document from which we drew our screenshot, “How we’re putting a price on carbon pollution.”

- Press release from office of Prime Minister Trudeau (with links to details).

- Carbon price fuel-charge rates.

- Materials on carbon pricing from Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission.

To Punish the Saudi Regime, Tax Carbon

It’s often said that a carbon tax is first and foremost a tax on coal. I’ve probably said it myself, and David Roberts wrote as much the other day in his useful post for Vox, The 5 most important questions about carbon taxes, answered, pointing out that “A carbon tax hits coal first, hardest, and, at least early on, almost exclusively.”

Coal is first up in carbon taxing’s crosshairs for two reasons: its energy value comes almost exclusively from oxidizing carbon, whereas oil and gas burning also derives considerable heat from oxidizing hydrogen into harmless water vapor; and in the U.S. coal is used almost exclusively to generate electricity, a commodity that many other sources can make as well.

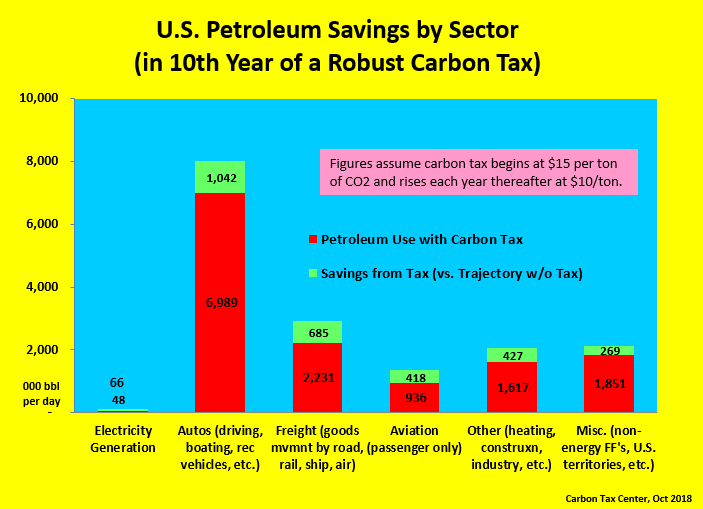

A decade after startup, a robust U.S. carbon tax would eliminate one-fifth of petroleum usage.

But oil would hardly be immune. A U.S. carbon tax — not a token, Exxon-style one but a robust fee on fossil fuels’ carbon content that ramped up steadily — would, before long, put a sizable dent in petroleum use. Ditto, natural gas, as the carbon tax level rises still higher.

A vigorous U.S. carbon tax would squeeze every owner of oil wells, petroleum infrastructure and hydrocarbon reserves: shareholders of Exxon, Shell, BP et al.; the Koch Brothers; and, most of all, Saudi Arabia’s national petroleum and natural gas company, Aramco — the world’s #1 oil extractor and largest holder of oil reserves.

The list of ways that a carbon tax would lessen oil use is nearly limitless. Driving, costing more, would begin to shrink. Fuel-efficient cars that stretch each gallon — higher-mpg vehicles and electrics — would gain market share. Freight movement by truck would start to be switched to rail and water, while supply chains became more local. Air travel would get pricier even as new aircraft engines were designed for greater fuel efficiency. In millions of economic decisions, proximity would be favored over distance and sprawl. Transit, cycling and higher-density development would gain.

These changes wouldn’t happen everywhere or immediately, of course, but they would gather strength as the carbon tax ramped up and society’s defaults got reset. And while we can’t micro-model every behavioral and structural change from carbon taxes (there are literally billions), the rich academic literature of price-elasticity makes it possible to rough-estimate the aggregate impacts of raising the prices of petroleum products for households and businesses.

In our modeling at the Carbon Tax Center, we estimate that a U.S. carbon tax that started modestly at $15 per ton of CO2 but increased each year thereafter by $10 per ton would, by its tenth year, shrink U.S. oil usage by 3.3 million barrels a day, cutting usage by one-fifth.

The NY Times caption of this Hani Mohammed / Associated Press photo it ran on Oct 17 read: “The Saudi-led war in Yemen has become one of the worst humanitarian disasters in years.”

That shrinkage amounts to more than 3 percent of current world oil consumption. A drop of that magnitude — even ignoring that many other countries would follow suit — would deliver a powerful one-two punch to Saudi pockets: lesser sales and a lower price.

With less money to throw around Washington and the Middle East, the corruptive power of the Saudi regime would begin to diminish. Its wherewithal to bomb Yemen back to the Stone Age, silence dissident journalists like Jamal Khashoggi, punish Canada simply for expressing “grave concern” about arrests of activists in Saudi Arabia, and so on — and immunize itself by spreading cash around U.S. universities, think tanks, artistic institutions — would be diminished as well.

All of which makes another reminder that the benefits of taxing fossil fuels according to their carbon content go beyond even helping arrest climate damage. Human rights activists — indeed, everyone who wishes to see justice done for the brutal murder of Mr. Khashoggi — should join the movement to tax carbon emissions.

Issue that will affect my vote? Climate change. Because anything else that we get wrong, we can revise in 10 years. But not this one.”

Susan Donaldson of Cambridge, Mass., with the final word in The New York Times’ “What Motivates Your [Midterms] Vote” letters section, Sunday, Oct. 21.

Five Key Sentences from New York magazine’s IPCC Blockbuster

David Wallace-Wells, the writer for New York magazine who jolted us last year with his searing climate-change story, The Uninhabitable Earth, has posted a follow-up, UN Says Climate Genocide Is Coming. It’s Actually Worse Than That.

You guessed right, the sequel is about the new IPCC report. We began the week covering the report’s first-time recommendation of a high carbon price to drive emission reductions. We can’t fully do justice to Wallace-Wells’ latest with a summary — it’s too layered for that. To convey a sense of his argument and his urgency, we’re excerpting five key passages (disclosure: some are longer than mere sentences), with comments.

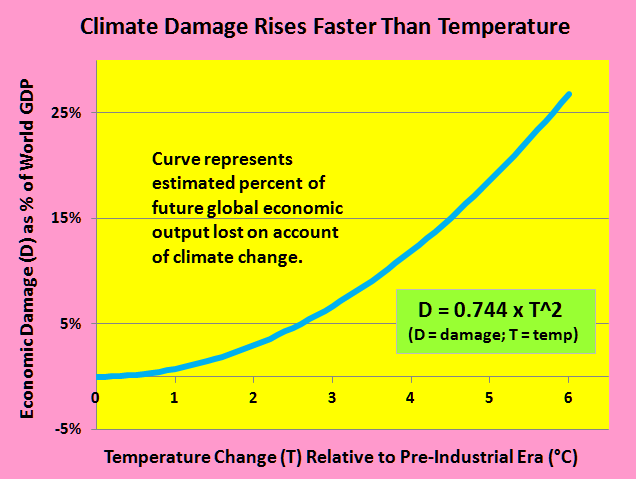

David Wallace-Wells: Barring the arrival of dramatic new carbon-sucking technologies, which are so far from scalability at present that they are best described as fantasies of industrial absolution, it will not be possible to keep warming below two degrees Celsius — the level the new report describes as a climate catastrophe. As a planet, we are coursing along a trajectory that brings us north of four degrees by the end of the century. The IPCC is right that two degrees marks a world of climate catastrophe. Four degrees is twice as bad as that. And that is where we are headed, at present — a climate hell twice as hellish as the one the IPCC says, rightly, we must avoid at all costs. (emphasis added)

Doubling the rise in temperature quadruples the anticipated damage. We drew up this curve to illustrate our June 2017 post, “Showing the Cost Side of the Climate Equation in a New Light.”

Carbon Tax Center: It’s worse than that. The most likely “shape” of the planetary climate-damage curve (or function) is a quadratic. (See graphic, from our June 2017 post, Showing the Cost Side of the Damage Equation in a New Light.) Doubling the temperature rise doesn’t double the damage, it quadruples it. Tripling the rise magnifies the damage nine-fold. The silver lining, if there is one, is that each increment of temperature rise we can prevent through societal action pays back more than proportionately in damage avoidance.

DW-W [this sentence is from his previous passage]: New carbon-sucking technologies … are so far from scalability at present that they are best described as fantasies of industrial absolution.

CTC: We agree.

DW-W: Because the numbers are so small, we tend to trivialize the differences between one degree and two, two degrees and four. Human experience and memory offers no good analogy for how we should think about those thresholds, but with degrees of warming, as with world wars or recurrences of cancer, you don’t want to see even one.

CTC: Goodness, yet another way in which human cognition militates against fully grasping and grappling with climate change. We thought Dale Jamieson’s magnificent 2014 book, Reason in a Dark Time: Why the Struggle Against Climate Change Failed, and What It Means for Our Future, covered all the obstacles to understanding and action: It’s hard to attribute the myriad consequences we see in the world to climate change… Evolution built us to respond to “rapid movements of middle-sized objects,” not to the slow buildup of insensible gases in the atmosphere. And of course, climate change is the world’s largest and most complex “collective action problem,” in which each of us, acting on our own desires, contributes to outcomes we neither desire nor intend. And many more, to which Wallace-Wells has added the new one, above.

DW-W: Nothing in the IPCC report is news … not to the scientific community or to climate activists or even to anyone who’s been a close reader of new research about warming over the last few years. That is what the IPCC does: It does not introduce new findings or even new perspectives, but rather corrals the messy mass of existing, pedigreed scientific research into consensus assessments designed to deliver to the policymakers of the world an absolutely unquestionable account of the state of knowledge.

CTC: That’s helpful to those of us in the trenches. It aids us in seeing why the release of old news — include the lede that limiting the earth’s average temperature rise to 1.5°C is pretty much off the table — was served up by important media as news, period.

DW-W: The IPCC has also, thankfully, offered a practical suggestion, proposing the imposition of a carbon tax many, many times higher than those currently in use or being considered — they propose raising the cost of a ton of carbon possibly as high $5,000 by 2030, a price they suggest may have to grow to $27,000 per ton by 2100. Today, the average price of carbon across 42 major economies is just $8 per ton. The new Nobel laureate in economics, William Nordhaus, made his name by almost inventing the economic study of climate change, and his preferred carbon tax is $40 per ton — which would probably land us at about 3.5 degrees of warming. He considers that grotesque level “optimal.”

CTC: Yesterday we posted the comment by our colleague Thomas Sterner, declaring that Nordhaus’s “choice to label the 3.5°C [temperature rise] as optimal is … unfortunate.” Today we would rather dwell on the brighter side, that the IPCC for the first time called not just for a carbon price but for a high one, as we reported on Monday.

DW-W: A carbon tax is only a spark to action, not action itself.

CTC: Yes … and no. No, because a robust carbon tax will be far more than a mere spark — it will stimulate enormous changes in behavior, investment, decision-making and innovation, all of it toward vastly lessened use of carbon fuels. Yes, because the tax itself doesn’t reduce emissions, rather it instills incentives that will provoke the reductions.

We think the article is well worth reading. Let us hear your take.

From Sweden, A Deeper Dive Into Last Weeks’ Economics Nobels

As a companion piece to our post earlier this week, IPCC: Not just a carbon price, but a really high one, we reprint a post last week from the University of Gothenburg (Sweden), on the award of the 2018 Economics Nobel Prize to William D Nordhaus, Yale University, New Haven and Paul M Romer, NYU Stern School of Business, New York, USA. We’ve edited it slightly for readability.

These are two very well-deserving winners, according to Thomas Sterner and Ola Olsson, professors at the School of Business, Economics and Law at the University of Gothenburg.

Nordhaus and Romer have developed methods for answering some of the currently most critical and challenging questions of how to create long-term economic growth and global welfare. Thomas Sterner, professor of environmental economics at the School of Business, Economics and Law at the University of Gothenburg described both Nobel Prize winners as pioneers in their fields and likes the combination of them:

Their research generates knowledge about what type of policies should be pursued in order to solve the global climate problem and at the same time give people a decent standard of living. Nordhaus was a pioneer and defined the climate issue as an important research field that he focused on in many fundamental articles in leading journals. In a way, he should have won the Nobel Prize a long time ago.

Thomas Sterner, photographed by the author in NYC in 2014, says William Nordhaus’s Nobel was overdue despite concerns about his work.

“Both winners really deserve the prize,” said Ola Olsson, professor of economics at the University of Gothenburg. “They were strong candidates individually, but I suppose the decision to have them split the prize is a bit surprising.”

William D. Nordhaus was one of the first economists to include the climate in economic growth models. His so-called DICE model has become somewhat of an industry standard among both supporters and critics. The model (or the family of models it has led to) has been the centrepiece of intense discussion regarding assumptions, results and recommendations.

And the criticism has not been unfounded. Nordhaus has, despite being a pioneer, downplayed the need for climate measures or has promoted policy that today would appear to pose a great risk to many people, according to Sterner. He does indeed support the idea of climate measures and policy intervention, yet at a mild level with low climate taxes.

Says Sterner:

In his articles, Nordhaus arrives at scenarios with a rise in temperatures of 3.5°C by the year 2100 (and a continued increase thereafter) as being optimal. Admittedly he discusses several scenarios and as a good scientist has several caveats about unexpected non-linearities etc. The choice to label the 3.5°C as optimal is still unfortunate. This is in stark contrast to the IPCC report that was published today, which advocates attempts to stick to the Paris agenda’s lower goal of 1.5°C rather than 2 °C. So, Nordhaus is not even close to these goals and considers 1.5 degrees totally impossible. About the 2-degree goal, he writes that it will not be possible to achieve “without negative emissions by the middle of this century,” something Nordhaus probably considers to be out of the question.

Paul M. Romer’s model of endogenous economic growth has been central in research ever since his most important article was published in 1990. Romer shows how technological progress can be integrated into the analysis of long-term economic growth. The issues analyzed include how private companies can produce technological ideas despite the fact that these ideas often can be described as so-called public goods that anyone can use.

“Romer’s research complements Nordhaus’s in a very interesting way,” Sterner said, “since he has studied the mechanisms that drive economic growth and that are utilized to improve macroeconomic models like DICE, in which Nordhaus has integrated a climate economics module. Romer emphasizes the importance of endogenous growth that is based on ideas and research. This is precisely the type of research that will be needed to make the technological development more sustainability oriented,” said Sterner.

Olsson added: “Romer’s analysis has had a strong impact on how we view long-term economic growth in developed countries that is driven by technological innovations.”

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- …

- 170

- Next Page »