We’re finally catching up with last week’s two big climate-policy stories: the new IPCC report on the dire consequences if global temperatures rise more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, and the awarding of the Nobel Prize in economic science to climate-policy pioneer William Nordhaus of Yale.

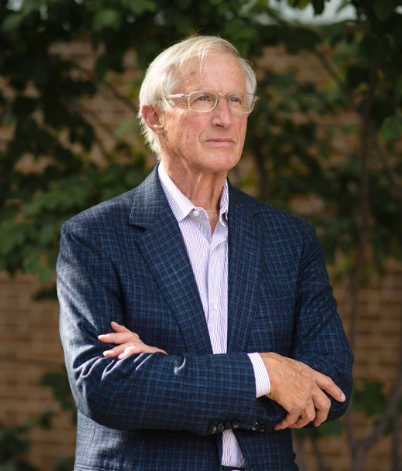

Nobel Laureate Nordhaus, in New Haven last week. Photo by Monica Jorge, courtesy NY Times.

A clear thread links the two stories: earth’s climate — and literally human society — faces repeated, widespread, unmanageable disruption unless the world’s nations and peoples begin a sharp and complete U-turn from fossil fuels to carbon-free energy; and this requires not just a “price on carbon” but a high one, as the New York Times spelled out in the headline of perhaps the paper’s key story last week.

Not only that, the price must be considerably higher than Prof. Nordhaus, the dean of climate-damage modeling, has called for throughout his illustrious careeer.

The story, by Times climate-economics reporter Brad Plumer, warrants quoting at length:

More than 40 governments around the world, including the European Union and California, have now put a price on carbon, either through direct taxes on fossil fuels or through cap-and-trade programs. But many of them have found it politically difficult to set a price high enough to spur truly deep reductions in carbon emissions.

The concept of carbon pricing received another implicit endorsement on Monday from the Nobel Prize committee, which awarded Yale’s William D. Nordhaus a share of the 2018 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Science for, among other things, making a case that “the most efficient remedy for the problems caused by greenhouse gas emissions would be a global scheme of carbon taxes that are uniformly imposed on all countries.” (emphasis added)

Plumer noted that since the 1970s, Prof. Nordhaus has “argued that companies that burn fossil fuels should be taxed at a rate that reflected the harms they were imposing on the rest of the world.” Needless to say, the companies would pass on most if not all of these carbon taxes in the form of higher prices for fossil-fuel derived electricity, gasoline and diesel fuel prices, etc. — a feature rather than a bug since these price incentives would do more than any other competing policy measures to motivate the companies themselves, along with millions of other decision-makers to change behavior, make investments and pursue innovations to minimize their tax exposure and, thus, shrink national and global use of fossil fuels and resultant carbon emitting.

“Economists have long been enthusiastic about carbon pricing because of the policy’s efficiency,” Plumer wrote in The Times. “Give companies a financial incentive to reduce their fossil-fuel use, and they will find creative and cost-effective ways to do so without the need for heavy-handed government regulations.”

That’s essentially our view at the Carbon Tax Center, except that we don’t necessarily view direct regulations like car-mileage standards as heavy-handed — just less productive than advertised, due to their scattershot, reactive nature; overrated, you might say.

How steep must a carbon tax (or carbon price “delivered” under a cap-and-trade permit system) be to enable the climate catastrophe of 1.5°C or greater temperature rises? As Plumer notes, the IPCC report estimated that the global-average price to emit a ton of CO2 pollution must be at least $135 by 2030, and perhaps as great as — are you ready? — $5,500.

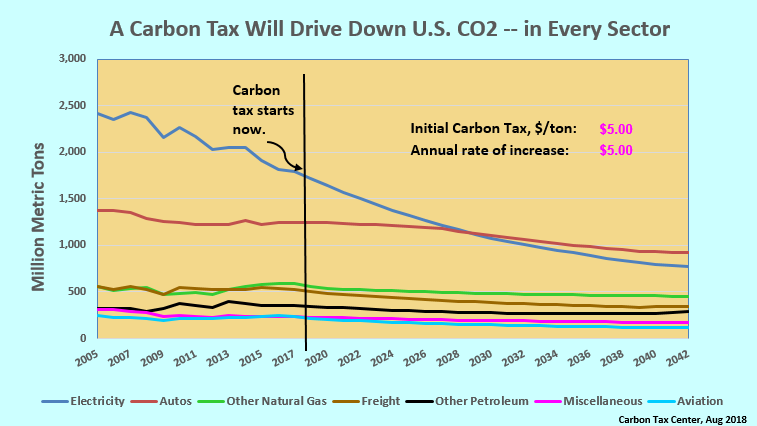

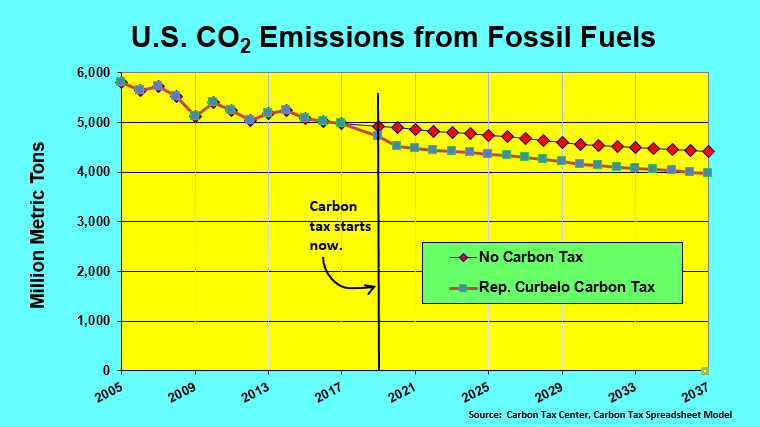

The bottom end of the range, at least, is right in line with what CTC has been advocating since roughly 2010, with a carbon tax starting at $12.50 per ton of CO2 and rising by $10/ton each year. As we never fail to point out, within a decade the tax, passing $100/ton and still rising, would cut U.S. emissions by roughly one-third from today’s levels. While stronger medicine is almost certainly needed, we’ve tended to stick to that trajectory to stay within the lines of political feasibility — a convention we would gladly bend if the carbon tax, once implemented, proved more acceptable to the public and elected officials.

Plumer’s wonderfully informative article hints at that possibility:

Policies that are widely popular with voters, such as mandates for renewable energy, can help reshape the political landscape to make more ambitious climate action feasible. And policies that spur innovation and drive down the cost of cleaner alternatives to fossil fuels, such as electric vehicles, could potentially make higher carbon prices more palatable.

In other words, as the perceptive Vox journalist David Roberts pointed out several years ago, continued advances in (and broadening uptake of) wind power, solar PV, electric cars, etc. could help carbon taxes be seen as a helpful bridge rather than a punishing hand. And, politically, that could make all the difference.

As for Nobel laureate Nordhaus, we haven’t been alone in criticizing him over the years for settling on an adamantly conservative formulation of carbon damages and the resulting “social cost of carbon” — one that arises from both his insistence on a high “discount rate” that shrinks future costs in present terms, and his exclusion from his modeling of the prospect that climate change will erode societies’ ability to generate new wealth by inhibiting the accumulation of technological and intellectual capital, among other losses.

Today, however, we applaud Prof. Nordhaus’s Nobel and share the hope he expressed in an interview this past weekend with The Times’ Coral Davenport, that “if we continue to work on this, the public will get there on the science, and make an exception to the toxicity of taxes.”

“It will help if [the carbon tax is] tied to something popular — if, as a result of the revenue from a carbon tax, you get a check in the mail, or it funds health care,” Prof. Nordhaus added in his interview. We’re all still searching for the right political formula. “I’m hopeful that grown-ups will take over and we will do what is necessary,” he said. “If we don’t, then things will just get worse and worse.”

CTC policy associate Bob Narus contributed information and ideas to this post.