The rifts over carbon pricing that have engulfed the climate movement in recent years and helped sink the 2016 Washington state carbon tax referendum softened noticeably at a public forum in New York’s Westchester County on Monday evening. Lines of convergence outweighed points of contention, perhaps signaling that proponents of transparent and robust carbon pricing can surmount our ideological differences and move forward together.

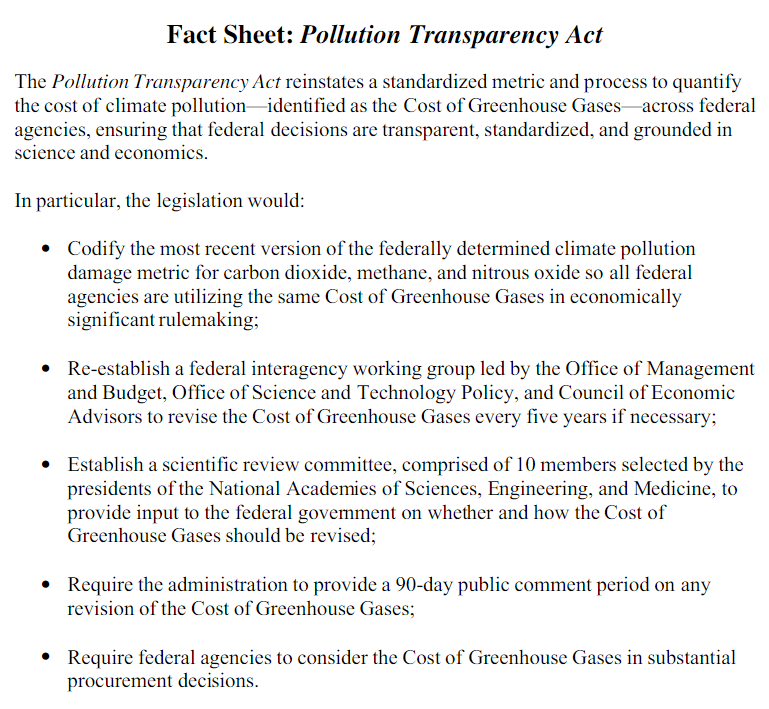

The forum, Carbon Tax: Solution to the Climate Crisis, was organized by local climate activist Andrew Ratzkin and held at Pace Law School, whose affiliate, the Pace Energy and Climate Center, has for decades been a bulwark of policy and legal analysis for energy efficiency, renewable energy and environmental taxation. While the four panelists — I was one — hale from different disciplines and generations, we were conversant with climate science, economics and organizing and respectful of each other’s endeavors.

The younger panelists, Dan Sherrell and Shiva Prakash, outlined the ambitious New York State carbon tax proposal developed by NY Renews that has attracted wide support — with sign-on from 143 organizations — through its pledges to apply the carbon revenues to protect low-income families, invest in sustainable energy technology, help workers transit out of fossil-fuel jobs, and remediate “front-line” communities disproportionately damaged by fossil fuel processing and combustion.

While there’s room to question whether spreading the revenues so broadly can achieve all four objectives, NY Renews rests its optimistic projections — which include, by 2030, a halving of New York CO2 emissions and creation of 150,000 net new jobs — on a detailed study by the U-Mass Political Economy Research Institute. The group also formulated its carbon-tax proposal through extensive consultation with advocates from labor, environment, low-income and environmental-justice communities — a far more holistic process than Carbon Washington followed in fashioning its doomed I-732 referendum, and one that should augur well for the eventual legislative effort.

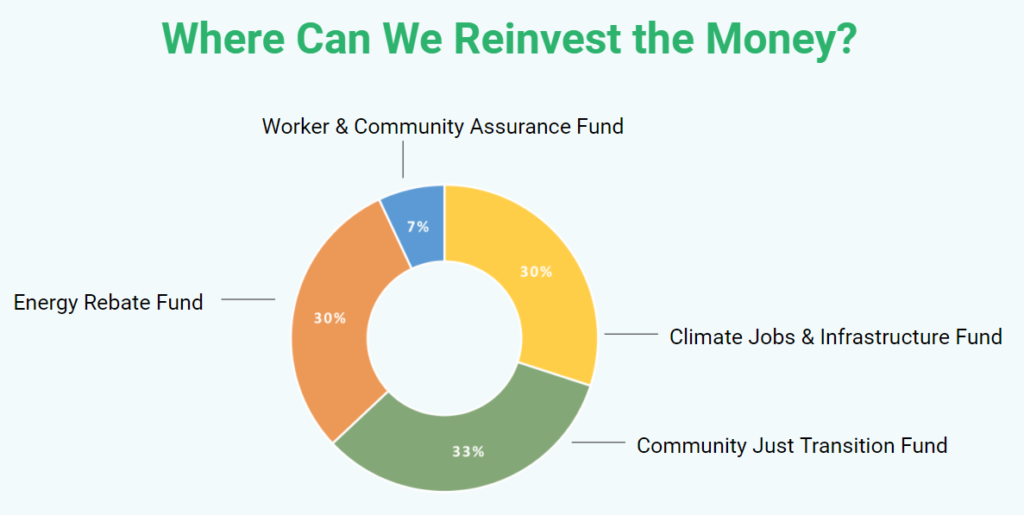

You may have noticed that my description led with the proposed use of the revenues, not the level of the tax. One reason is that the carbon tax amount in any state proposal tends to be constrained by “leakage” concerns over cross-border business flight as well as the political difficulty of getting too far out front of neighboring states; for the record, the NY Renews carbon tax would start at $35 per ton of CO2 and increase indefinitely at 5 percent a year.

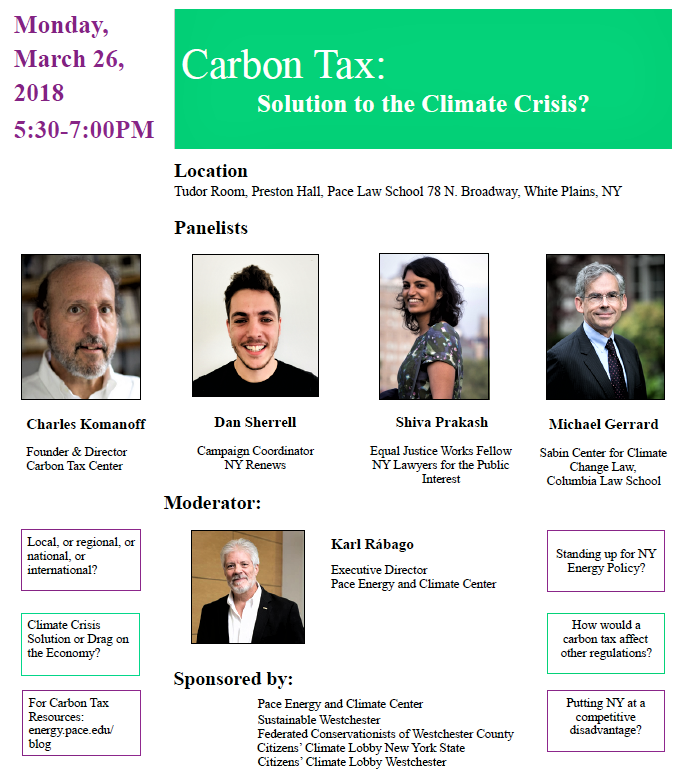

The other, weightier reason for emphasizing revenue use is that it has become the boulder on which carbon tax advocacy has splintered. Revenue-investment proponents like NY Renews, who tend toward the political left, want the carbon revenues applied to the “Green New Deal” elements outlined above (and shown in the graphic below) which collectively constitute what they call “the just transition” from coal, oil and gas to renewables.

An opposing revenue-neutral camp tends to be less overtly political, as exemplified by Citizens Climate Lobby, whose 60,000 national members insist on equal return of carbon “dividends” to households as a way of skirting left vs. right fights and building constituencies of support for raising the carbon tax or fee level (since the dividend checks rise at the same rate). The revenue-neutral camp also places greater trust in the ability of the carbon-price signal to motivate pervasive changes in investment, behavior, technology and societal values that will effectuate the flight from fossil fuels, whereas revenue-investors tend to disdain “market forces” and to eye carbon taxes primarily as a revenue source to pay for socially driven and governed wind, solar, weatherization, public transit and electrification.

While these categories are a gross simplification, a synthesis of sorts appeared to come into view on Pace at Monday, along these lines:

- Taxing carbon emissions is so essential AND politically difficult that establishing a U.S. beachhead is more important than demanding a perfect version.

- The impossibility of enacting a carbon tax at the federal level till at least 2021 leaves states as the locus for that beachhead for several years or more.

- Several factors render revenue-neutrality less imperative in state than federal carbon-taxing:

- The lower tax rates in most state proposals imply lesser need to dedicate revenues to dividends or other income-support;

- Greater political and cultural cohesion within states allows tailoring carbon-revenue investment to be more politically palatable;

- Greater role of coalition politics makes some revenue investment necessary to pass state legislation.

While it’s possible or even likely that initial state carbon taxes that are heavy on revenue investment might repel red-state members of Congress as “Christmas-tree” packages, that specter seems less salient than the need to get some carbon-tax boots on the ground — not to mention the need to overturn the G.O.P. majorities and shrink climate-denialist representation in Congress, period.

NY Renews’ proposed state carbon tax allocations.

These bullet points sharpen somewhat the long-established position of the Carbon Tax Center to support virtually any carbon tax formulation that doesn’t demonstrably worsen economic inequality. Still problematic for CTC, however, is the insistence of many revenue-investment adherents that their Just Transition include substantial allocations — as much as one-third, in the NY Renews proposal — to offset and remediate disproportionate fossil-fuel impacts on front-line communities.

Our position, which co-panelist Michael Gerrard also voiced, is that the fastest and surest way to reduce and eliminate those environmental injustices is to enact and ramp up the highest carbon tax that’s politically imaginable. Both Michael and CTC premise this on our conviction that the price signal itself is the salient policy tool within the carbon tax, and that a robust carbon charge will create powerful and ultimately irresistible incentives to reduce and eliminate fossil fuel use — and, thus, emissions and other impacts — across-the-board, not just in selected (wealthy and white) communities. It follows, then, that all communities, including but not limited to environmental-justice communities, will be better protected from both climate damage and “traditional” environmental insults if carbon tax proposals are free from what some lawmakers may consider special dispensations and can be legislated as high as possible.

We at CTC took a first stab at articulating this position in a 2016 blog post. We hope to elaborate on it soon and to elicit responses from NY Renews and other climate activists who carry the environmental-justice carbon-tax banner.

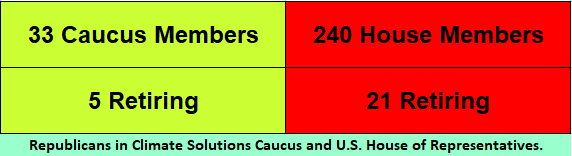

None of the Republican members have uttered a word in favor of carbon taxing, even the intendedly Republican-friendly “fee and dividend” espoused by the caucus’s catalyst,

None of the Republican members have uttered a word in favor of carbon taxing, even the intendedly Republican-friendly “fee and dividend” espoused by the caucus’s catalyst,  Nevertheless, Issa and the caucus’s other lame-duck Republican members have a rare opportunity: a full year still in office to speak their minds on climate (or other issues) without fear of being primaried by unabashedly denialist insurgents. They could push back against Trump’s climate lies and call on their party to assume its Rooseveltian mantle of environmental stewardship. In doing so, they could set a standard for their 28 Republican colleagues who hope to keep their seats and, by their caucus membership, have ostensibly committed themselves to pursuing climate solutions.

Nevertheless, Issa and the caucus’s other lame-duck Republican members have a rare opportunity: a full year still in office to speak their minds on climate (or other issues) without fear of being primaried by unabashedly denialist insurgents. They could push back against Trump’s climate lies and call on their party to assume its Rooseveltian mantle of environmental stewardship. In doing so, they could set a standard for their 28 Republican colleagues who hope to keep their seats and, by their caucus membership, have ostensibly committed themselves to pursuing climate solutions. Congestion pricing levies fees on vehicle travel into or within the core of a city. Singapore,

Congestion pricing levies fees on vehicle travel into or within the core of a city. Singapore,

The trope

The trope  Lifton, a psychiatrist who turned 90 last year, has long observed, lived among and written about the perpetrators and victims of some of the 20th Century’s most profound atrocities — the atomic bombings of Japan, the Vietnam War and, of course, the Nazi Holocaust. His writing humanizing the

Lifton, a psychiatrist who turned 90 last year, has long observed, lived among and written about the perpetrators and victims of some of the 20th Century’s most profound atrocities — the atomic bombings of Japan, the Vietnam War and, of course, the Nazi Holocaust. His writing humanizing the