The trope shown at left, about Trump “holding the planet hostage,” isn’t entirely new. But it came into sharper relief for me over the weekend as I read Robert Jay Lifton’s insightful new book, The Climate Swerve. And it gave added weight to the apostasy of a ranking Republican senator who earlier this month told the New York Times that Trump’s bluster toward North Korea may be setting the United States “on the path to World War III.”

The trope shown at left, about Trump “holding the planet hostage,” isn’t entirely new. But it came into sharper relief for me over the weekend as I read Robert Jay Lifton’s insightful new book, The Climate Swerve. And it gave added weight to the apostasy of a ranking Republican senator who earlier this month told the New York Times that Trump’s bluster toward North Korea may be setting the United States “on the path to World War III.”

The senator issuing the warning was Bob Corker (R-TN), chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. His words capped a 10-day raging argument in which Trump ridiculed Corker’s decision not to seek a third term next year, and Corker tweeted that “the White House has become an adult day care center” struggling to keep its main occupant in check. “He concerns me,” the senator said of the president. “He would have to concern anyone who cares about our nation.”

Corker’s blunt talk about Trump brought to mind his independent stance on climate in the months following the 2008 election of Barack Obama. The defeated GOP candidate, Senator John McCain, had been a backer of carbon cap-and-trade, as were many Congressional Democrats and nearly all of the major environmental organizations. Corker took a minority view, speaking out in favor of carbon taxing in a January 2009 hearing before the Foreign Relations Committee:

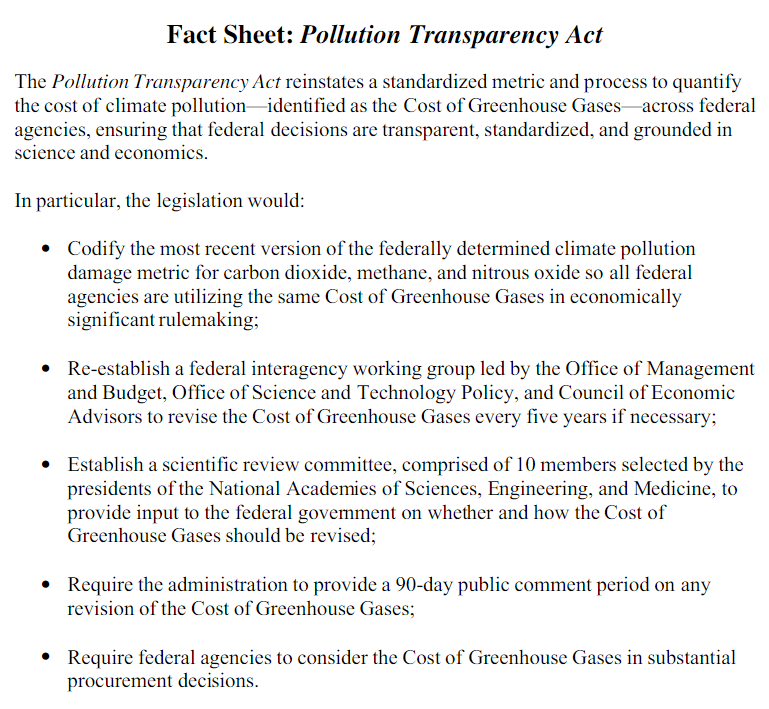

I wish we would just talk about a carbon tax, 100 percent of which would be returned to the American people. So there’s no net dollars that would come out of the American people’s pockets.

Not everyone back then viewed Corker as a straight shooter. Grist blogger David Roberts lambasted him for “talk[ing] his way inside the carbon policy tent and now … trying to burn it down” by diverting support from cap-and-trade. But the New Republic’s Brad Plumer insisted that “Bob Corker [is] making sense … for a fruitful conservative position” that’s revenue-neutral and transparent. (Roberts now blogs for Vox while Plumer writes for The New York Times.) Indeed, it’s not much of a stretch to credit Corker’s 2009 words as the launch pad for the Citizens’ Climate Lobby’s fee-and-dividend idea and its recent offshoot, the Climate Leadership Council’s carbon dividends approach.

Unfortunately, carbon taxing didn’t advance beyond the fringe in either political party, and climate rejection soon became an element of Republican tribal identity, leading Corker to give up on carbon taxes and on climate generally. And for more than a decade few public figures had much to say about nuclear weapons and the specter of nuclear war. That began to change this year with the launch of nuclear-capable missiles by North Korea and Trump’s vow that if “North Korea … make[s] any more threats to the United States, they will be met with fire and fury like the world has never seen.”

Trump has also repudiated the Paris climate agreement and taken steps to annul the Obama Clean Power Plan and to greenlight fossil fuel development across North America. Humankind now is staring at not one but two “apocalyptic twins,” in Lifton’s words: a nuclear threat and a climate threat. Both the parallels and differences between the two are the subject of Lifton’s new book, Climate Swerve, which appears in the immediate wake of climate furies that have devastated Houston, Puerto Rico and Northern California.

Lifton, a psychiatrist who turned 90 last year, has long observed, lived among and written about the perpetrators and victims of some of the 20th Century’s most profound atrocities — the atomic bombings of Japan, the Vietnam War and, of course, the Nazi Holocaust. His writing humanizing the hibakusha (literally, “explosion-affected people”) of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and his explorations of the “malignant normality” embodied in the Cold War policy of “mutually assured destruction” galvanized public and political support for both the Kennedy-Khrushchev 1963 ban on atmospheric nuclear weapons testing and the Reagan-Gorbachev 1987 agreement eliminating short- and intermediate-range nuclear missiles.

Lifton, a psychiatrist who turned 90 last year, has long observed, lived among and written about the perpetrators and victims of some of the 20th Century’s most profound atrocities — the atomic bombings of Japan, the Vietnam War and, of course, the Nazi Holocaust. His writing humanizing the hibakusha (literally, “explosion-affected people”) of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and his explorations of the “malignant normality” embodied in the Cold War policy of “mutually assured destruction” galvanized public and political support for both the Kennedy-Khrushchev 1963 ban on atmospheric nuclear weapons testing and the Reagan-Gorbachev 1987 agreement eliminating short- and intermediate-range nuclear missiles.

It was only recently, however, that Lifton turned his attention to climate change. His brand-new book, eloquent and spare, has two tracks. In one he encourages what he calls the climate swerve — humanity’s “evolving awareness of our predicament” as we collectively cause, and face, climate ruin. In the other he seeks to bring to climate consciousness his perspective on what was, at least until this year, mankind’s turn from the brink of nuclear ruin.

This passage (slightly edited for readability, emphasis added in bold) is emblematic:

Nuclear and climate threats are separate and different from each other. With nuclear weapons, the mind must contemplate specific things — bombs that bring about revolutionary dimensions of blast, heat, and radiation. The imagined catastrophe is immediate and decisive, and the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki provides a model of unprecedented slaughter and suffering. With climate threat, the mind encounters no new physical entities or things, but rather an incremental sequence of an increasingly inhospitable habitat, a progression rather than an explosion, and a series of projections of what can be expected, as opposed to a clear display of ultimate destruction.

Nevertheless, an irony — and a strangely hopeful one — of Lifton’s book is that Hurricanes Harvey and Irma have produced, for all who care to see, painfully “clear displays of ultimate destruction.” Lush Puerto Rican farmlands and woodlands flattened and laid barren are now literally concrete, as are obliterated California vineyards. Lifton himself put these facts front and center in an op-ed for The New York Times earlier this month (emphasis added):

Climate images have never been able to convey our full planetary danger until now. The extraordinary recent four-punch sequence of hurricanes … threatened the lives of millions of people, obliterated their homes and has raised doubts that some places will ever recover … The hurricanes … provided imagery equivalent to the danger, imagery equivalent to nuclear disaster. When we viewed photographs and film of the annihilated cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, we sensed that the world could be ended by nuclear weapons. Now these hurricanes have conveyed a similar feeling of world-ending, having left whole islands, once alive in their beauty and commerce, in ruin.

I imagine I’m not the only one brought to tears but also galvanized by those words. They appeared in print on the same Sunday morning, October 8, that Bob Corker called the New York Times to warn about Trump putting us “on the path to World War III.”

While there may not be a direct line from Lifton’s op-ed to Corker’s speaking out, both of their testimonies are proof that we’re not hostages. We still have voices, and both the advance of climate ruin and the renewed chances of nuclear ruin require that we raise them. Republican voices like Corker’s are especially critical, but anyone with power and a pulpit shouldn’t hesitate to use them. And for the rest of us, a letter to our local paper, a Facebook post, or plain old face-to-face sharing can help others grasp the gravity of the risks we are living with and how we can overcome them.

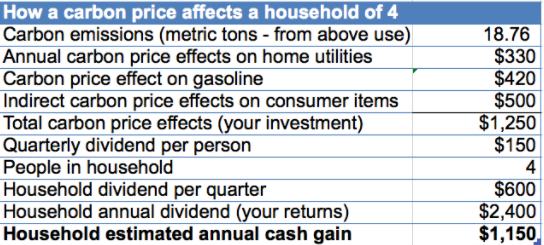

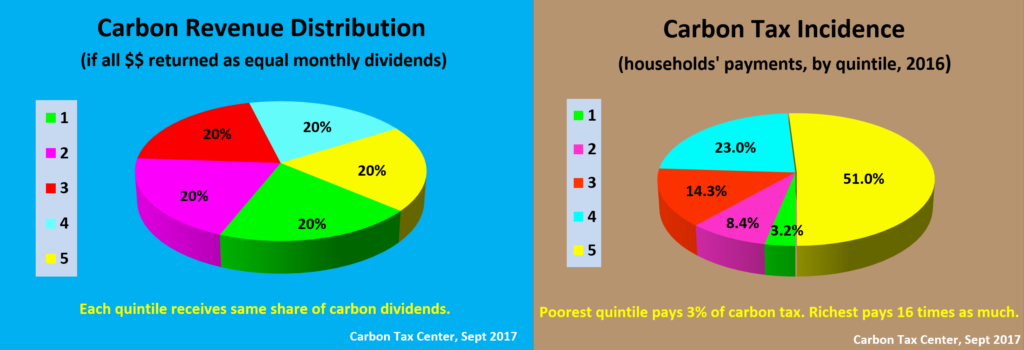

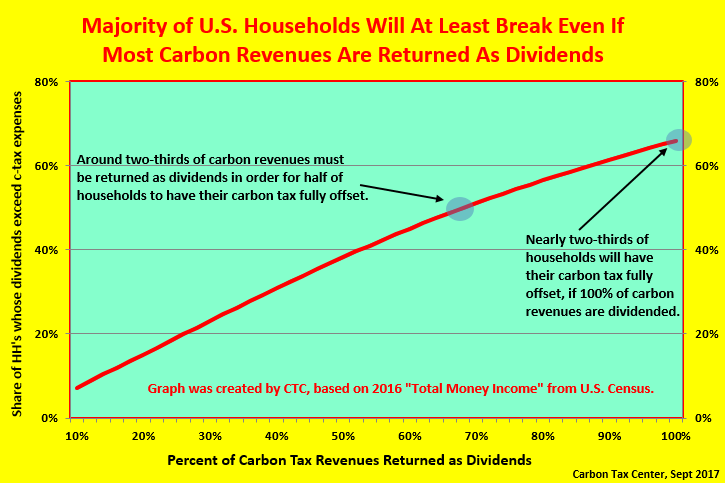

These disparities underlay Bernie Sanders’ “political revolution” campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination last year. And they added fuel to the sense of white grievance that energized Donald Trump’s successful run for the presidency. They also bolster the case for “carbon dividends” — the idea of distributing all or nearly all carbon tax revenues equally to U.S. households popularized as carbon fee and dividend by the non-partisan

These disparities underlay Bernie Sanders’ “political revolution” campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination last year. And they added fuel to the sense of white grievance that energized Donald Trump’s successful run for the presidency. They also bolster the case for “carbon dividends” — the idea of distributing all or nearly all carbon tax revenues equally to U.S. households popularized as carbon fee and dividend by the non-partisan  The progenitors of CLC’s carbon dividend plan, James Baker and George Shultz, are “exemplars of the outcast center-right GOP establishment,” as I described them recently in the

The progenitors of CLC’s carbon dividend plan, James Baker and George Shultz, are “exemplars of the outcast center-right GOP establishment,” as I described them recently in the