Trump is bling, and bling is fossil fuels: The Boeing 757-200. The limo’s. The helicopters.

And also, evidently, the buildings. Not just the marble, but the lights, the escalators, and the machinery: motors, fans, compressors to (over) cool and heat.

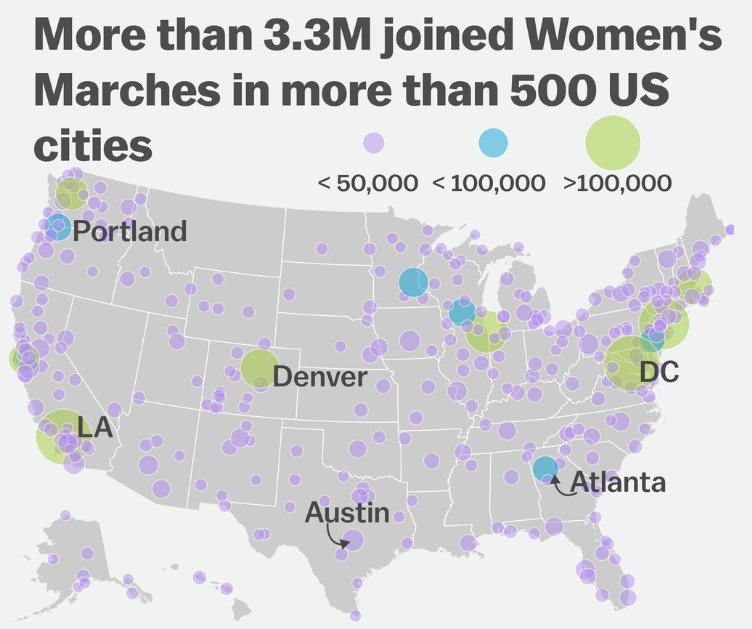

The spa in Trump SoHo, a hotel ranked in the highest 1% in carbon emissions in its class. Photo from Luxury Travelers Guide.

We awoke this morning to find the Trump brand’s conspicuous energy consumption confirmed in spades, in EnergyWire. Thanks to their lead story, At blinged-out Trump hotels, ‘green’ isn’t part of the brand, we now know that out of nine Trump-branded properties in Manhattan that submitted energy use data under New York City’s energy benchmarking law, six were in the bottom 20 percent for energy efficiency, based on consumption per square foot.

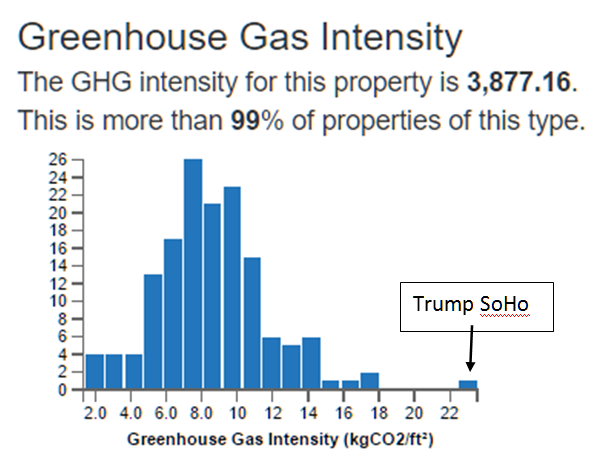

Since those buildings are, ahem, huge, their outsize per-area energy usage puts their total fuel use and carbon emissions off the charts. To grasp how much, we zeroed in on one building, the Trump SoHo. According to the EnergyWire story, the combined hotel-condominium was in “the bottom [worst] 1 percent of properties of its type and size for energy intensity.”

We logged into NYC’s excellent Energy and Water Benchmarking Web site, navigated to Hotels and typed in the Trump SoHo address, 246 Spring Street. A bunch of graphs popped up, including the one at right, below, denoting CO2 emissions per square feet. From it, we were able to calculate that in 2014, the most recent year with available data, the fossil fuels burned to run the Trump SoHo emitted around 10,000 metric tons of CO2. (Calculations are at bottom.)

That’s a tough figure to put in perspective (okay, it’s within hailing distance of total carbon emissions for the entire country of Liechtenstein, which clocked in at 14,000 metric tons in 2013). So we converted it to dollars, using the carbon tax level that Trump’s Secretary of State-designate, Rex Tillerson, appeared to endorse on a handful of occasions during his tenure as ExxonMobil CEO: $25 per metric ton of CO2.

Histogram from City of New York energy benchmarking for hotels. We used x-axis reading for Trump SoHo.

Ten thousand times 25 is 250,000, so at the (admittedly hypothetical) Tillerson rate, the Trump SoHo would be dunned around a quarter of a million dollars a year for its carbon emissions. (More precisely, the hotel’s electricity and energy providers would pay the tax and attempt to pass it through in higher charges.)

At the higher carbon tax levels that would make truly monumental dents in emissions, say, $100/ton, the annual charge would be a million bucks a year. That might get someone’s attention (and provoke an intervention by the energy managers from the Trump-branded 40 Wall Street skyscraper in Lower Manhattan, which improbably had an excellent (91) Energy Star score, according to EnergyWire).

But beyond poking fun — and it’s important to keep poking the new administration — the Trump properties’ energy profligacy matters a great deal for our planet. That’s because energy efficiency is critically important for reducing climate-damaging emissions.

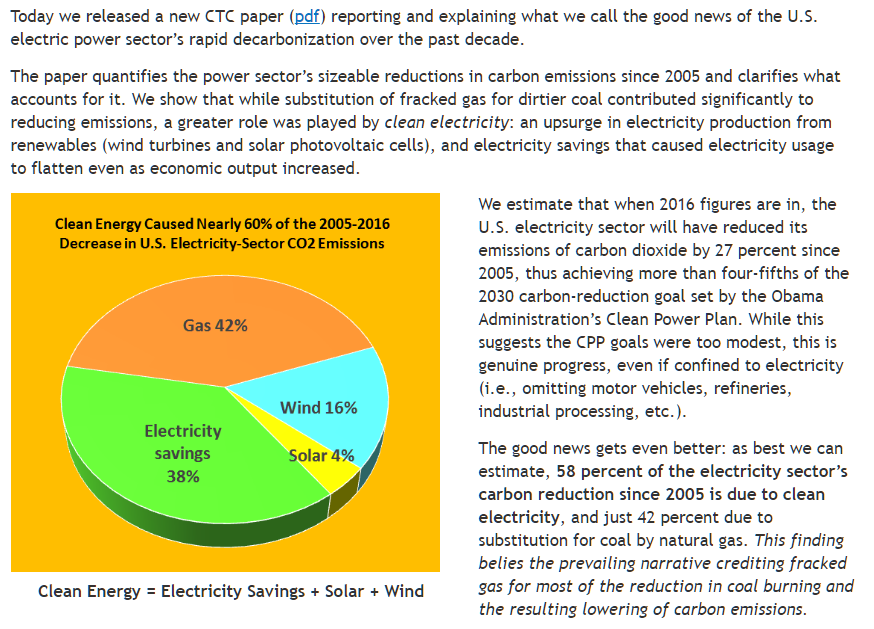

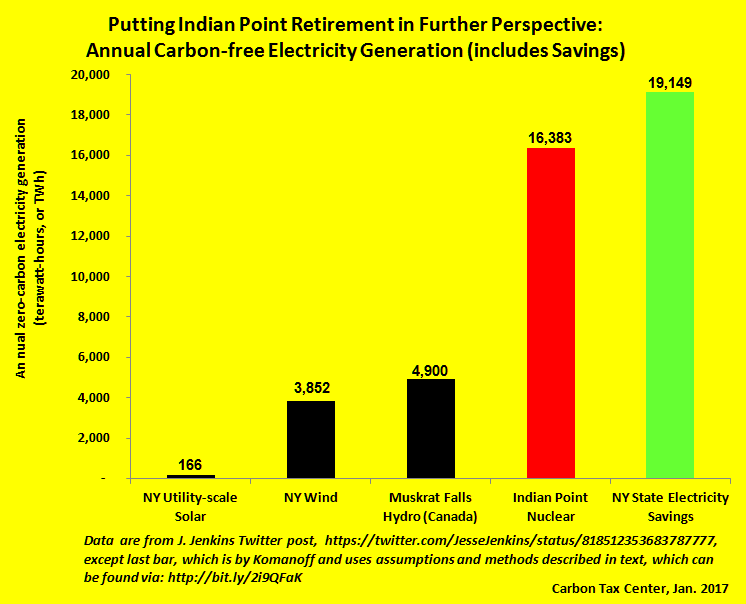

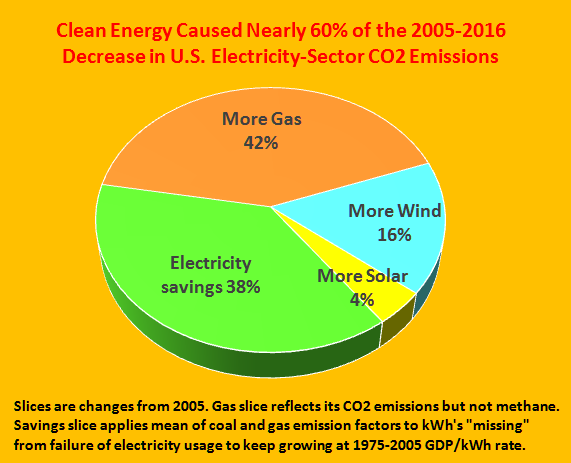

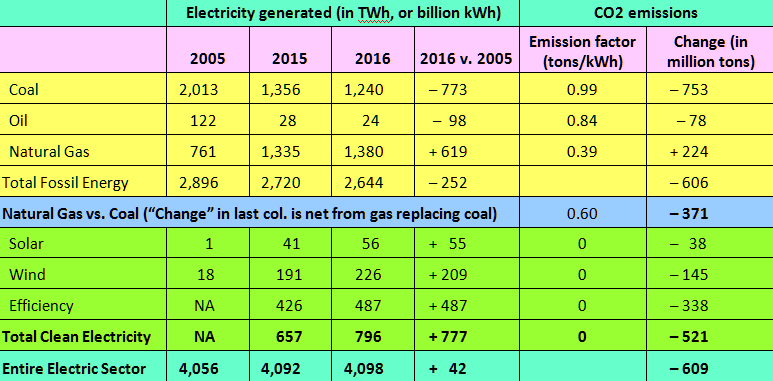

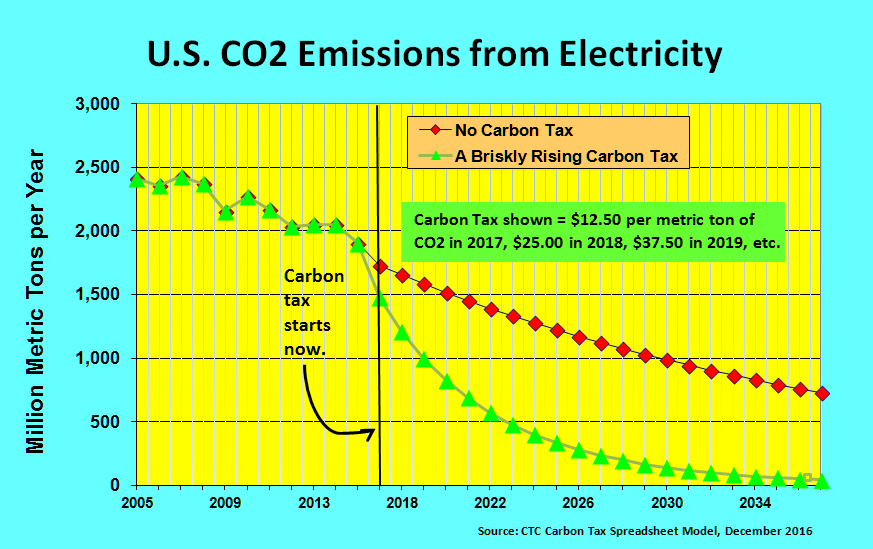

For four decades and counting, visionaries like Amory Lovins and practitioners like the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy have documented (and fought to win supportive policies for) the capacity to provide more energy services (warmth, light) with fewer energy inputs. Last month, we published a Carbon Tax Center report identifying electricity savings that have caused electricity usage to flatten even as economic output increased, as the unheralded but key factor in the 25 percent cut in CO2 emissions from the U.S. electricity sector since 2005. (Shorter blog version here.)

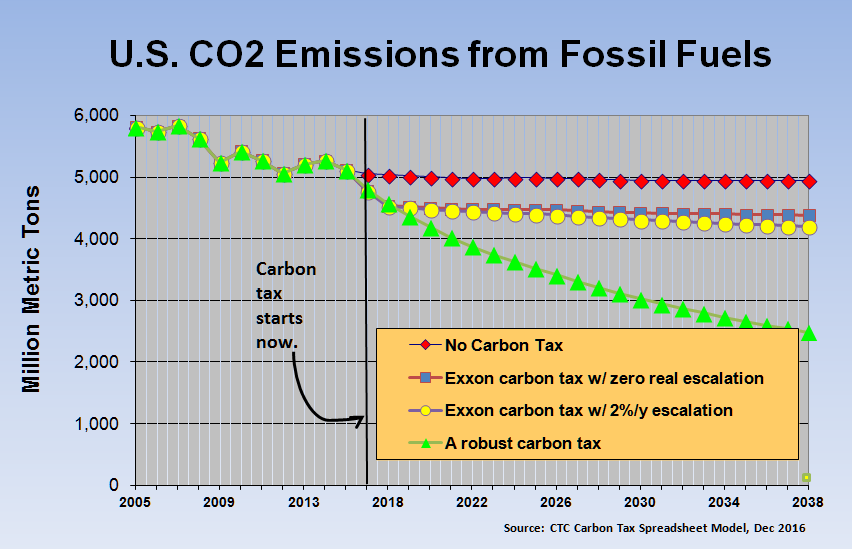

There’s been a lot of debate about whether our 45th president can bring back coal. One way to stop that — and avert more fracking too — is to maintain and accelerate progress in U.S. energy efficiency, especially in buildings. In that endeavor, as in virtually every other, the right direction is full speed away from anything spelled T-R-U-M-P.

Note: As we were posting this article, we saw a post by the Energy and Policy Institute presenting strong evidence that ExxonMobil lobbied the Massachusetts state legislature to oppose two carbon tax bills, one of them revenue-neutral, during the 2016 session, i.e., when Tillerson was still CEO.