Erik Solheim, head of the United Nations Environment Program, quoted in “At U.N. Meeting, Diplomats Worry Trump Could Cripple Climate Pact”, by Coral Davenport, New York Times, Nov. 15.

No Free Ride for New Climate Outlaw

Jan. 24, 2017 update: French presidential candidate (and former prime minister) Manuel Valls yesterday renewed Nicolas Sarkozy’s Nov. 2016 call for a carbon border tax on imports from the United States, saying “When Donald Trump declares some kind of economic war on Europe, we must be ready.” More in this Fox News (!) story.

This post is by Chris Hope, a prominent U.K. climate change policy researcher who served as a lead author and review editor for the Third and Fourth Assessment Reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. It is lifted more or less intact from Chris’s Nov. 15 post, A proportionate response to Trump’s climate plans. We have edited slightly for grammar and added several notes. — CTC.

During the U.S. election campaign, Donald Trump said he would dismantle the country’s domestic climate change policies and withdraw the U.S. from international climate agreements, most notably the Paris agreement which came into force earlier this month. In the week since he became President-Elect, he has given every indication that he is serious in his intentions.

A British economist has a policy response to the world’s #1 climate denier.

So how should the rest of the world respond? It is tempting to indulge in wailing and gnashing of teeth, but in the real world of a Trump Presidency, this is unlikely to be effective. What is needed is a proportionate response. In France, former president (2007-2012) Nicolas Sarkozy has proposed what may well be the most efficient and effective measure, a climate change tax levied upon all US goods imported into Europe.

[CTC: Chris is referring to “border tax adjustments” — import fees levied by carbon-taxing countries on goods manufactured in non-carbon-taxing countries. World Trade Organization rules permit countries with carbon taxes to adopt “non-discriminatory harmonizing tariffs” to protect energy-intensive trade-exposed industries by eliminating the competitive advantage enjoyed by exports from countries that don’t tax carbon emissions. These tariffs also create incentives for non-carbon taxing countries to adopt carbon taxes, since harmonizing tariffs represent revenue that the exporting country could garner by imposing its own carbon tax. Our Border Adjustments Web page has more information.]

How large should such a tax be? If it is to be proportionate, it should cover the harm caused to the Earth from the production of the goods, a harm that will not be reflected in their price if the U.S. presses ahead with the unfettered use of fossil fuels. Let’s consider some ballpark numbers. The Gross Domestic Product of the US in 2015 was about $18 trillion. U.S. emissions of greenhouse gases in the same year were about 7 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent. Dividing one quantity by the other, we find that every thousand dollars of U.S. production involves the emission of about 0.4 tonnes of CO2 equivalent.

[CTC: Chris’s 7 billion tonne CO2-equivalent figure is sourced to definitive USEPA data and comprises somewhat more than 5 billion tonnes of CO2, one billion tonnes of CO2-equivalent from methane, and perhaps 0.6 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent from nitrous oxides, hydrofluorocarbons (HFC’s) and other heat-trapping gases.]

The best estimate we have of the global harm caused by these emissions comes from integrated assessment models, like my PAGE09 model which gives a mean value of about $150 per tonne of CO2 if valued by an average citizen in Europe, or $250 per tonne of CO2 if valued by an average U.S. citizen (U.S. citizens are on average about 50% richer than European ones, so they should value an equivalent physical harm more highly).

Applying these mean values as an ad valorem tax on imports of USA goods to Europe results in a tax of about 6%, if the European valuation of harm is used, or 10% with the U.S. valuation. These are higher, but not dramatically so, than Sarkozy’s proposal of a 1–3% tax on US imports.

How much might such a climate tax on U.S. imports raise? The EU presently imports about 400 billion Euros of US goods and services per year. So a 6% tax rate would raise about 25 billion Euros per year, and a 10% rate would raise about 40 billion Euros. If imports of U.S. goods and services have a price elasticity of -1, these revenues would be about 6% or 10% lower respectively.

[CTC: The implied revenue reduction of 25-40 billion euros, or $27-$43 billion in U.S. currency, represents potential U.S. trade losses. They equate to around $100 per capita, or roughly $400 per U.S. family of four.]

If adopted, this idea could be refined further by levying higher rates on U.S. goods that released a great deal of greenhouse gases during their production, and lower rates on others. And of course, in order not to be hypocrites, we in Europe would introduce a strong, comprehensive climate change of about $150 per tonne of CO2 equivalent on our own activities too. But that is only common sense.

After The Trump Win

Was it really just a month ago that the “Access Hollywood” tape was sending the Trump candidacy into its death throes, the Republican Party was melting down, and the first-ever Congressional debate over carbon taxing seemed in store for 2017?

It sure looked like it, as I wrote in this space on October 9:

Democratic control of both the White House and Congress clears a path for a federal carbon tax without having to somehow vault over GOP denialists. Which could make next month’s ballot referendum in Washington state, Initiative 732, even more momentous. Enacting the country’s first carbon tax wouldn’t just produce a template for other states; it could spark national legislation establishing a U.S. tax on carbon emissions, perhaps as early as 2017.

Sad to say, I-732 went down to defeat Tuesday, resoundingly, 59% to 41% (those figures, updated Nov 11, supersede the 58-42 Election Night result). But that loss is but a charred matchstick in the burnt landscape we awoke to Wednesday morning: a Trump presidency, a continued GOP lock on Congress, and a hard-right Supreme Court.

Where do climate campaigners, and carbon tax proponents in particular, go from here? As I search for answers, I’m bearing these points in mind:

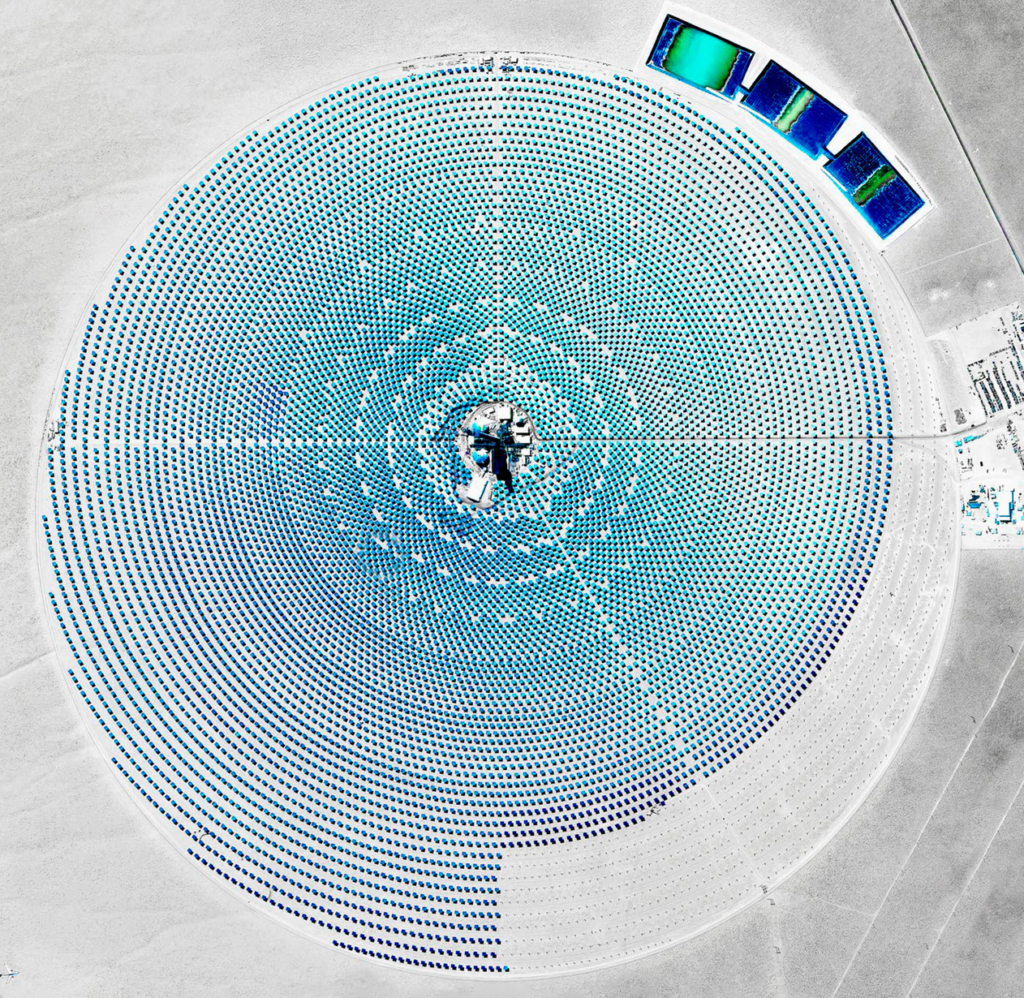

1. Solar, efficiency and wind will keep advancing — Yes, R&D will be cut, maybe also tax credits for wind turbines and solar PV. And some states’ rules and regulations affecting siting and financial treatment for renewables and efficiency could turn for the worse. But clean energy’s rapid growth isn’t going to stop. Tech progress, plummeting costs, and the advent of business models to handle logistics and financing remain powerful forces. As clean energy spreads, so will the constituency for aggressive climate policy — perhaps even carbon taxes, a possible scenario laid out last year by David Roberts of Vox (he called it “strategic sequencing of climate policies”) that is especially pertinent today.

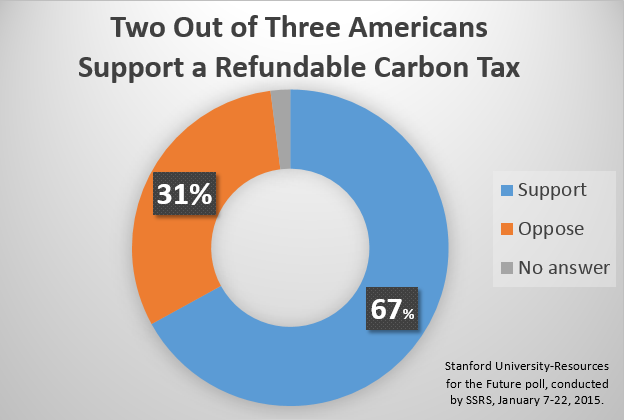

Polling stumbled this week, but these results are still striking.

2. Americans may be less averse to carbon taxes than you think — It’s a shame I-732 didn’t win, not least because the heroic activists at Carbon Washington worked their butts off for it. But let’s not write off carbon taxing. The defeat of the Washington referendum owes a lot to the unfortunate split within the green movement. Carbon taxes that prioritize equity and protect low and moderate-income families can be politically popular, as suggested by a 2015 poll by Stanford and Resources for the Future — the only national polling to date of explicitly revenue-neutral carbon taxing.

3. The Clean Power Plan is in the rear-view mirror — Don’t fret too long over the likely dismantling of the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan. Events have largely overtaken it, with U.S. coal-fired power generation cut in half in just a decade. Calculations we’re finalizing at the Carbon Tax Center will show that by year’s end the U.S. electricity sector will have already made nearly all of the carbon reductions the CPP demanded for it by 2030. And while much of that progress was sparked by EPA’s Mercury and Air Toxics rule that helped precipitate coal plant shutdowns, Americans’ long-standing support for clean air will make it hard for even a President Trump to dial back those standards.

Crescent Dunes Solar Energy Project, Nevada, aerial photo by Benjamin Grant, courtesy NY Times. Solar farms and rooftops will keep sprouting despite Trump.

4. The Law of Reaction (“Pride Goeth Before a Fall”) — We’ve seen it time and again: over-reaching that precedes a disastrous stumble: A nuclear industry spokesman publicly inviting a prominent TV news anchor to “come see the safety features at our new flagship reactor at Three Mile Island,” just before the infamous meltdown in 1979. The bombshell that seismic attenuators were installed backwards at one of the Diablo Canyon reactors just as the new Reagan administration was rushing to water down atomic safety regs in 1981. This syndrome isn’t mere coincidence; the media crave counter-narratives. With the Republican Party now “owning” climate change, extreme weather will give us many opportunities to put them on the defensive.

5. Uniting Our Movement — The split in the green movement over I-732 laid bare genuine divisions among climate activists, over leadership and inclusion as well as policy. We can use the new enforced policy hiatus to get better at listening to each other. Carbon tax advocates, myself included, need to commit to sharing and even ceding leadership to more diverse voices. We can also do better at conveying why we place carbon taxes at the center of climate policy, and why we believe they are the best policy complement to divestment and keep-it-in-the-ground campaigns.

Am I “whistling past the graveyard” here? I don’t know, frankly. Trump’s victory is traumatic, and it’s really hard to face the future. But face it we must and will. There’s too much at stake. Fighting for a livable planet and a humane society is what I’ve done my whole life. I’m not stopping now, and I know neither are you.

Naomi Klein Is Wrong On The Policy That Could Change Everything

On this last day before the elections, the afternoon light was waning in my Manhattan office and I thought I could be done fending off attacks on I-732, the Washington state carbon tax initiative.

Not so fast. A CTC supporter wrote me, cryptically, “Naomi Klein should know better by now, no?” I checked Klein’s Twitter feed, @NaomiAKlein, and, uh oh, there it was: a piece by Klein in The Nation, The Carbon Tax on the Ballot in Washington State Is Not the Right Way to Deal With Global Warming.

The policy that could do the most to start changing everything is on the ballot in Washington state.

I read her piece. It’s mercifully brief, just ten paragraphs, so I thought I would let it go. But Klein, author most recently of This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate, is charismatic, fluent and highly visible in the climate movement. And just about everything she said in her Nation piece is so misinformed or short-sighted that it feels important to respond. So here goes, in point-counterpoint.

Klein Paragraph 1: The imperatives of the climate crisis and the logic of economic austerity are at war—and Washington State is on the front lines.

CTC: Powerful lede, but is Klein actually tagging I-732 with the dreaded “austerity” label? What exactly does she mean? (Spoiler alert: she never says.)

Klein Paragraph 2: So-called “revenue-neutral” carbon pricing — whereby the proceeds are used to fund tax cuts — has long been a cherished hobbyhorse of free-market economists and the odd Republican who favors climate action. It’s also the policy of choice for big polluters like ExxonMobil. And now this right-wing friendly model is being pushed in Washington State, thanks to Initiative 732.

CTC: “Tax cuts.” A percentage point cut in Washington’s state sales tax — the principal means by which I-732 ensures that raising energy prices through a carbon tax won’t injure low- and middle-income families — is dismissed as a mere “tax cut,” a phrase that of course conjures giveaways to the hedge-fund class. What Klein labels right-wing is actually friendly to and designed for the very groups she purports to care about: families below or near the poverty line; undocumented immigrants; over-leveraged folks struggling to stay middle-class.

Klein Paragraph 3, abridged: [If I-732] is approved by voters, it would be a disastrous precedent that could set back the climate justice movement for a decade — time that we simply can’t afford to lose.

CTC: Klein turns logic on its head. Following a decade of nearly total legislative silence on carbon taxes — a silence imposed not just by Republican denialists but by a myopic U.S. green movement — Klein frets that enacting an actual carbon tax in the USA and blowing open the door to a possible national carbon tax will set back climate action for another ten years?

Klein Paragraph 4: Some have accepted the logic that something is better than nothing, even arguing that a “tax swap” could substitute for a just transition to a low-carbon economy. The evidence proves otherwise. In British Columbia, two-thirds of the tax cuts have ended up in corporate pockets, while carbon emissions have been rising in recent years and the fracking industry has boomed.

CTC: By design, most of the BC carbon tax revenues end up in taxpayers’ pockets through personal income tax cuts as well as a low-income tax credit. A 2015 study by University of Ottawa graduate students found BC’s carbon tax “highly progressive” distributionally. In any case, I-732 is explicitly and intentionally structured differently, to apply 75 percent of carbon tax revenues to cut the Washington sales tax.

Yes, CO2 emissions in British Columbia are up slightly since 2012, but that’s because the BC tax level has stayed fixed. In contrast, the Washington carbon tax would rise 3.5% a year faster than the general inflation rate. And If fracking has boomed in BC, don’t blame the province’s carbon tax for its lack of a keep-it-in-the-ground movement.

Klein Paragraph 5: By some estimates, I-732 would raise gasoline and electricity prices less than 15 percent by 2040 in Washington State—hardly enough to jumpstart an urgent, sweeping phase-out of fossil fuels. Meanwhile, it would offset carbon revenues by cutting taxes for big corporations, including major polluters. (According to the Seattle Times, Boeing could see windfalls of tens of millions annually.)

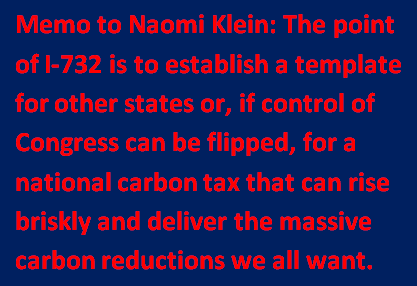

CTC: Klein’s math is off; by 2040, the tax-caused rise in gasoline prices would be 25 percent. But the bigger point she ignores is that a carbon tax in any one state like Washington (or a lone province like British Columbia) can’t be set high because of interstate competitive pressures — which is also why I-732 sets aside 10-15 percent of its revenues for tax reductions for businesses like Boeing. The whole point of the Washington state initiative is to establish a template for other states or, if control of Congress can be flipped, for a national carbon tax that can rise briskly and deliver massive carbon reductions, as we noted in a blog post last month.

CTC: Klein’s math is off; by 2040, the tax-caused rise in gasoline prices would be 25 percent. But the bigger point she ignores is that a carbon tax in any one state like Washington (or a lone province like British Columbia) can’t be set high because of interstate competitive pressures — which is also why I-732 sets aside 10-15 percent of its revenues for tax reductions for businesses like Boeing. The whole point of the Washington state initiative is to establish a template for other states or, if control of Congress can be flipped, for a national carbon tax that can rise briskly and deliver massive carbon reductions, as we noted in a blog post last month.

Klein has five more paragraphs, but in the interest of time let’s cut to the chase:

Klein Paragraph 9: A paltry, revenue-neutral carbon tax simply cannot deliver the massive green energy investments and community-driven solutions we all need. Science-based climate action means an unprecedented, rapid, and decisive shift to renewables; a truly equitable carbon tax can play an important role in spurring the transition, but it won’t work unless we make the polluters pay, and put their immoral profits to work repairing the damage they have knowingly created. The way to do that is to mobilize the broadest possible coalition—led by the front-line communities who stand to benefit most from building a cleaner and fairer economy.

CTC: Talk about “making polluters pay” is great rhetoric, but in our society as currently configured that includes all of us who flip on switches, turn on ignitions and buy stuff. And since the society we live in (to echo another post of mine last month) doesn’t appear to favor massive green energy investments and community-driven solutions, we have to rely even more heavily on robust carbon taxes; and these need to be largely revenue-neutral if they’re going to (i) not drive low-income families further into poverty and push middle-income families deeper into debt, and (ii) be politically acceptable.

Klein’s call to put fossil fuel company profits to work repairing damages is more of the same empty rhetoric. The task before us is to shrink, shame and strangle the fossil fuel companies. If Klein can offer a way to do that more quickly and effectively than a briskly rising U.S. carbon tax — one that I-732 can start paving the way for — I’m all ears.

Until then, could she please turn down the volume?

Addendum: CTC contributor Dan Lazare presciently dissected Klein’s limited comprehension of the power of carbon taxing almost two years ago, in this space, with Why Is Naomi Klein So Cool on a Carbon Tax? It’s a great read.

Washington State’s coming vote on carbon taxes exemplifies the power of people to attack climate change meaningfully. It started with the efforts of one person, Yoram Bauman, who led the charge. Then more than 300,000 people signed a petition to put the issue on the ballot. And now the 4.2 million registered voters of Washington State will have a chance to register their position by checking yes or no on Nov. 8. That’s climate action, and leadership.”

Letter published in Nov. 1 New York Times from Janet E. Milne, professor and director of the Environmental Tax Policy Institute at Vermont Law School.

To The Left-Green Opponents of I-732: How Does It Feel?

The Friday-afternoon tweet from Greenwire nailed it: @Koch_Industries & @VanJones68 united in $$ battling Wash. state #carbontax measure.*

Though they could also have tweeted: Fossil-Fuel Right & Doctrinaire Left team up to battle Wash. state #carbontax measure.

“Green jobs” champion Van Jones is flanked by fellow I-732 opponents Charles & David Koch in this Nov 4 tweet. Digitally available via @EENewsUpdates.

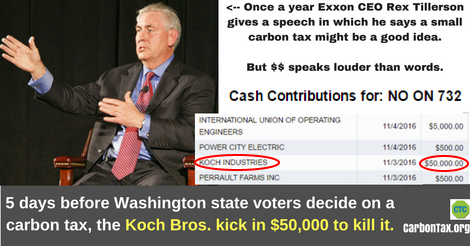

The occasion was the news that Koch Industries just poured $50,000 into the coffers of the No On 732 forces. As everyone knows who wasn’t slumbering through the past two decades, the Hard Right takeover of Congress and dozens of statehouses and legislatures owes much to Koch Industries’ prolific bankrolling of reactionary candidates and lobby groups. Brothers Charles and David Koch are billionaires many times over, thanks to Koch Industries’ empire of pipelines, refineries, mines and wells that for generations have spewed carbon pollution into the atmosphere for free.

The Koch brothers are no dummies. They know what fellow fossil fuel exec Robert E. Murray told Kirk Johnson and Coral Davenport of The New York Times the other day: Passing I-732 to enact a carbon tax in Washington state could ignite a trend that “would eliminate the use of all fossil fuels.”

We at the Carbon Tax Center know it too. Which is why we’ve pulled out all the stops to educate Americans from Washington and beyond on the merits of that state’s carbon tax referendum and its potential to kick open the doors to national carbon taxing.

What’s been hard to fathom is the drumbeat from so-called left greens like visionary climate hawk and political activist Van Jones in opposition to the Nov. 8 ballot measure.

In the past two weeks we’ve had to contend with bizarro posts like “Here’s Why a Carbon Tax Helps Fossil Fuel Companies, Not the Environment” (an op-ed in AlterNet by Food & Water Watch) and “Why Exxon Loves the Carbon Tax—and Voters Should Not” (the same group’s op-ed in the ironically named Yes! magazine).

It was just a matter of time before the Koch Bros. cut a check to stop I-732. Meanwhile, the Yes forces have no Exxon money; nor would they take any.

We responded to both last week — before today’s filing by No On 732 revealed that the Koch brothers are helping finance the opposition. Needless to say, only an ideologue could believe that Exxon’s once-a-year opining for hypothetical carbon taxes counts for more than $50,000 in Koch Brothers money against an actual one. (Click here to see the Koch contribution in the No On 732 list.) And sure enough, there was a lot more ideology than reason on display in a press event yesterday in which leading left greens inveighed against I-732.

We were allowed to listen in, but not to speak or ask a question. No transcript or audio has been made available, but here’s a sample of what we jotted down from speakers’ remarks. (Remember, they were addressing a carbon tax that has been meticulously designed to make Washington state taxes less regressive, primarily by dedicating the lion’s share of revenues to slice a full percentage point off the WA sales tax.)

You’re doing climate policy on the backs of the poor. — Van Jones, CEO of Green for All

A “neutral” 732 is perpetuating a one-sided economy of wealth and privilege. This is not a time for more tax cuts for corporations. — Heather McGhee, President, Demos

We stand united to defeat 732. We agree that climate policy cannot be promoted on the backs of the poor. — Mary Kay Henry, president, Service Employees International Union

We’re working on an alternative proposal. There are difficult legal questions. We’re beefing up the struggle after the election. — Rich Stolz, Director, One America

The last quote was in response to a reporter’s question about the alternative to I-732 that the left greens in Washington have talked about for years but never actually written. (Spoiler alert: writing the kind of ballot measure the left greens purport to want is devilishly difficult, in large part because the various groups have competing as well as overlapping interests, which are hard to reconcile. A revenue-neutral measure like I-732 didn’t face that problem.)

The untethering of those quoted statements from the reality of I-732 — a measure meticulously designed around a sales tax cut so low- and middle-income families aren’t harmed — is distressing to me personally. I’m a long-time admirer of every one of the organizations whose leaders I’ve just quoted. As I’ve said many times in this space, I’m a green and I’m on the left. I want to be partnering with Van and Heather and Mary Kay and Rich, not fighting them.

But a carbon tax is too central to climate, and climate is too central to all of our common struggles, for me to sit by and let ideology get in the way of sensible, pragmatic advocacy.

If “friends don’t let friends drive drunk,” it should also be true that activists don’t let activists drive policy from rhetoric.

To Van Jones et al., how does it feel to be on the same side as Charles and David Koch? That’s the corner you’ve painted yourselves into.

*Author’s Note: E&E News tweet lightly edited for clarity.

Fighting in the Trenches Doesn’t Excuse Ignorance on Carbon Taxes

A charitable way to view Food and Water Watch’s intemperate and misguided attacks this week on carbon taxing is that these energetic activists are so consumed with fighting fracking, pipelines and mines that they haven’t had time to absorb how carbon taxes can help dry up the “need” for new fossil fuel infrastructure.

An alternative take on their screeds in Yes Magazine and AlterNet is that FWW inhabits an ideological blind corner that sees carbon taxing as a neoliberal plot to undermine the climate movement rather than as a policy tool that can play a decisive part in keeping fossil fuels in the ground, forever.

From Food & Water Watch’s home page. Shouldn’t you understand what a carbon tax is before you castigate it?

Whichever, FWW’s case is toxic, simplistic and wrong. Toxic because its emergence in the home stretch of the carbon tax campaign in Washington state threatens to move critical Yes votes into the No camp on Nov. 8. Simplistic because the arguments suggest that FWW hasn’t grasped the ABC’s of carbon taxes. And wrong because the group’s criticisms of the British Columbia carbon tax — the Washington referendum’s political and policy template just across the border — are rife with errors.

Just look at the headlines of FWW’s op-eds.

“Here’s Why a Carbon Tax Helps Fossil Fuel Companies, Not the Environment” (FWW’s op-ed in AlterNet)

A carbon tax helps fossil fuel companies? Sure, like cigarette taxes help tobacco companies and sugary drink taxes help soda companies. Or taxes on bullets would help the makers of assault rifles. In real life, carbon taxes are a mortal threat to fossil fuel companies because they destroy demand for fossil fuels — both by shrinking end-user demand (as people drive less, businesses adopt energy-efficiency measures, etc.) and by helping renewables out-compete them.

“Why Exxon Loves the Carbon Tax—and Voters Should Not” (FWW’s op-ed in Yes! magazine)

Yes, from time to time Exxon CEO Rex Tillerson utters a positive word about carbon taxes — token ones that make for good p.r. but are 5-10 times smaller than those for which CTC and other carbon tax advocates campaign. Indeed, we’ve wondered if Exxon’s reputed support is a maneuver to turn naïve climate advocates against carbon taxing — “if Exxon wants it, it must be bad.” Fact is, Exxon doesn’t want robust carbon taxing; and even if it did, a policy should be judged on its merits, not by one of its putative supporters.

Left-leaning economists like Robert Reich, Joseph Stiglitz and Robert Frank support carbon taxes. So does Ralph Nader. So did Bernie Sanders, in his outspoken, unvarnished, way, throughout the Democratic Party primaries. How much is Exxon paying them?

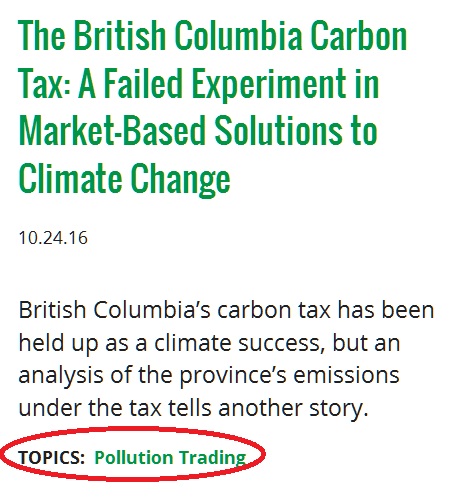

Both FWW op-eds draw from the group’s new report, The British Columbia Carbon Tax: A Failed Experiment in Market-Based Solutions to Climate Change. The report is wrong from the title, down. (Hint: a carbon tax isn’t a market-based policy; see below.)

FWW tips its hand in its thumbnail for the report on its home page (you’ll need to page down 5-6 times). The “tag” for the report is “Pollution Trading.” FWW could have written “Potato Chip” and been more on point. Carbon taxes are direct charges on fossil fuels according to their carbon pollution content, period. They’re simple and transparent. Nothing is traded, which means no market.

FWW could learn from Tim DeChristopher and fight for carbon taxes and against carbon infrastructure.

Pollution trading, or cap-and-trade, “puts a price on carbon” via the back door — hiding the price, if you will, in carbon “permits” that are traded on pollution “markets.” CTC and other carbon tax advocates spent countless hours in 2007-2010 explaining why pollution trading was ill-suited for internalizing climate costs into the prices of fossil fuels, and exhorting big green groups like NRDC and EDF to back straight-up carbon taxes instead. (Our Web page delineating cap-and-trade’s drawbacks actually has “dead ends” in its URL.)

We’re well acquainted with emissions progress in British Columbia, from our December 2015 report, British Columbia’s Carbon Tax: By The Numbers. Sadly, the analytical criticisms of the British Columbia carbon tax in Food & Water Watch’s report don’t hold up any better than the rhetorical ones. Here’s a sampling.

Claim: “Taxed greenhouse gas emissions rose by a total of 4.3 percent between 2009 (the first full year that the tax was in place) and 2014. (FWW report, p. 4).”

Fact: A proper comparison must start in 2007, the last pre-tax year, or 2008, when the carbon tax took effect, on July 1. Using 2009 as a baseline is nonsensical since the tax had already gone into effect; it’s also biased on account of the 2009 recession (which FWW mistakenly located in 2008, see p. 2). For the record, BC 2014 emissions from fossil fuel combustion of 43,940 kilotonnes of CO2 were 1 percent less than emissions of 44,363 kT in 2007 and 44,244 kT in 2008. (See methodological note at end.)

British Columbia’s GDP has grown considerably from 2008, creating the emissions pull that tends to accompany economic activity. Normalized per unit of GDP, 2014 emissions were down by 12% from 2008 and by 11% from 2009. While that’s not enough, it’s around what one would expect from a “starter” carbon tax such as BC’s.

Claim: “British Columbia’s carbon tax failed to reach the reduction targets necessary to ensure a sustainable climate, demonstrating that carbon taxes are not a viable policy solution to climate change.” (FWW report, p. 2)

Fact: Straw-man alert! It’s true that BC’s carbon tax is too low by an order of magnitude to get “80 by 50” or similar deep cuts. Its value, and that of the similarly designed (though more aggressive) Washington state carbon tax proposal, is to establish the template of carbon taxes, particularly revenue-neutral ones, so that not just provinces or states but entire nations can put robust, briskly rising carbon taxes in place. Indeed, earlier this month PM Trudeau announced that all of Canada will take precisely that step, starting in 2018.

Claim: “A carbon tax is theoretically designed to raise the cost of greenhouse gas emissions, but if those costs are refunded it almost defeats the purpose. The price of climate change is only included at the point of emissions, but since it ultimately is returned to the companies and individuals, over time it may create little disincentive to pollute.” (FWW report, p. 3)

Fact: No, the revenues from the British Columbia carbon tax aren’t “refunded” or “returned,” they’re recycled on an economy-wide basis via tax cuts that are distributed to companies and individuals without regard to the amount of carbon tax they may have paid. This separation of revenue distributions (benefits) from carbon tax incidence (payments or costs) is fundamental to any “revenue-neutral” carbon tax, whether it’s one that primarily uses tax swaps such as BC’s or Washington’s proposed tax, or the “fee-and-dividend” model advocated by Citizens Climate Lobby. FWW’s miscomprehension on this basic point speaks volumes.

Fact: “Individuals ultimately shoulder the majority of the costs of the British Columbia carbon tax, and lower-income individuals . . . bear a disproportionate burden.” (FWW report, p. 8)

Comment: We labeled this point a fact because the first part is true. Individuals, as final consumers of virtually everything our economies produce, do bear the costs of carbon taxes. That’s unavoidable, and it’s also the point, as we’ve written countless times. That’s why it’s important that carbon taxes such as BC’s and Washington’s be revenue-neutral; it ensures that low-income families receive disproportionate shares of the tax reductions or dividend distributions and thus are kept whole despite higher energy prices.

The fight against fossil fuels stretches way back. I co-authored this 600-page report on coal pollution in 1972.

Claim: “Despite significant volatility in U.S. gasoline prices in recent years, the total number of vehicle miles traveled and household car travel demand changed very little in response to price fluctuations. Without sufficient alternative transportation options, people will continue to drive their cars regardless of significant changes in gasoline prices.” (FWW report, p. 6)

Fact: The supposed price-inelasticity of energy demand has become an article of faith for many on the political left — though whether it preceded or post-rationalized a distaste for energy taxes is hard to say. I’ve studied the price sensitivity of energy demand for decades and written about it extensively, most recently here. I can report that while gasoline is the least price-elastic of fuels, it’s far from inelastic (in my linked post I report a U.S. gasoline price-elasticity of around -0.35). This shouldn’t be surprising, insofar as most automobile use in both the U.S. and Canada is for non-work trips, which on average have a high discretionary component.

There’s more, but you get the point. Lest my criticisms appear harsh, I note that I sought to engage FWW director Wenonah Hauter in a dialogue on carbon taxes last winter, after she published a letter in the New York Times disparaging the tax in British Columbia.

After one back-and-forth, I wrote again and closed as follows:

Wenonah, like you, I’ve been in the trenches fighting fossil fuels for a long time. We may have different ideas about how to get to the same goal, but I hope we can both pursue that goal without running at cross-purposes.

She never replied.

Addendum (Jan. 5, 2017): Several CTC supporters have drawn our attention to the assertion in FWW’s Failed Experiment report that from 2005 to 2013 emissions fell further in Ontario, which didn’t have a carbon-pricing system, than in British Columbia, which did. According to FWW, this shows that “mandatory replacement of fossil fuel energy plants with renewable, carbon-free forms of energy can rapidly and permanently reverse emissions trends.” Not quite. Ontario had low-hanging fruit that BC lacked: coal-fired electricity generation. And what allowed Ontario to eliminate coal-fired generation and put up impressive carbon-reduction numbers was increased output from its nuclear power plants: from 2003 to 2013, coal-fired electricity generation fell by 38 billion kWh while nuclear output rose by 30 billion as the nukes were expensively “refurbished.” Carbon-free, yes, but not the “renewable” energy FWW would like to credit.

Methodological note: our calculations here, which add 2014 to the data in our year-ago report, exclude emissions from Public Electricity and Heat Production. This category — essentially electricity generation from burning fossil fuels — accounts for just 2 percent of BC emissions from fuel combustion but for nearly 20 percent in the rest of Canada. More importantly, that sector constitutes most of the “low-hanging fruit” for reducing carbon emissions, since electricity generation affords more opportunities for quickly and easily substituting low-carbon supply than any other major sector. Eliminating this category enabled us to compare changes in emissions over time — the heart of our analysis — on an equal basis between BC and the rest of Canada.

Washington State’s I-732: A Climate Measure for the Society We Have

Paul Goodman, a mid-century American apostle of transformational change, entitled a collection of his letters, “The society I live in is mine.” With apologies to Paul, whose unsparing but inspiring critiques of U.S. corporate government helped shape my generation of radical activists, I’m here to say that the Washington state carbon tax initiative, I-732, is the perfect climate measure for the society we have.

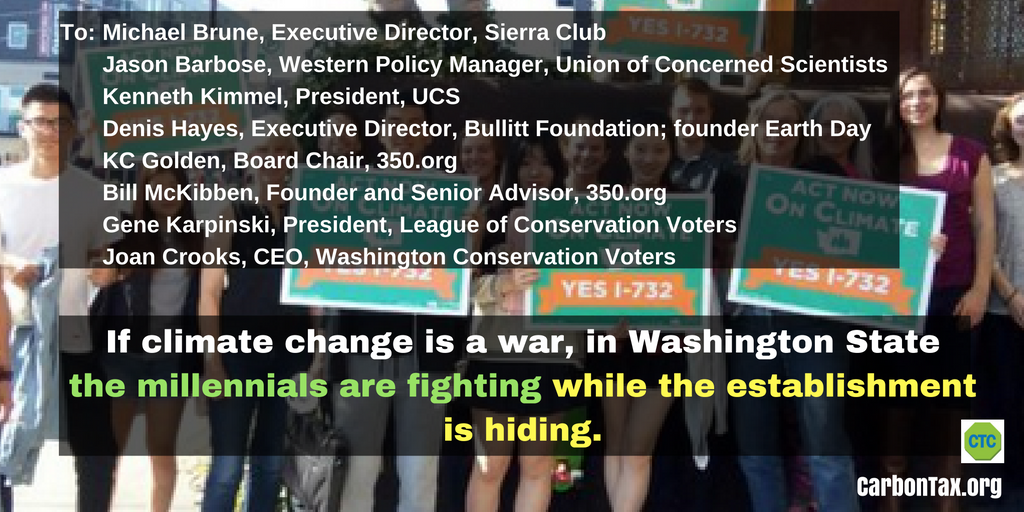

Calling out the old guard’s “deafening silence” (or worse) on the Washington state carbon tax.

I thought of Goodman today as I read the remarkable “Open Letter from the Millennial Leaders of Carbon Washington and the Yes-on-732 Campaign” to the green establishment leaders who are silent or oppositional on the initiative. Paul was an unabashed champion of youth and an instinctive foe of the old guard, most notably in his best-known book, Growing Up Absurd.

I believe Goodman, renowned for speaking directly, would have relished the millennials’ plain-spoken courage in calling out their heroes’ “deafening silence” on I-732. Devoted to participatory democracy, he would have applauded the millennials’ insistence that the climate crisis “belongs to more than just a handful of non-profit gatekeepers to decide what should be politically realistic and what isn’t.”

I also think that Goodman, a champion of rigor, would have pounced on the insubstantial arguments made by I-732’s “green” opponents, corrected their errors, and alerted them to the absurdity of climate advocates opposing a carbon tax that has advanced to an actual ballot proposition.

Here’s one of those arguments. It’s the first of three bullet points in the message by Washington Conservation Voters telling their members and supporters to vote No:

[I-732] relies solely on economic signals to drive down emissions, which allows all polluters to pay to continue to pollute instead of reducing emissions. Without a carbon cap, we can’t ensure that we will achieve the pollution reductions that are required in state law, but are currently unenforced.

Everything in that paragraph is correct. And all of it is utterly beside the point.

Yes, Initiative 732 relies solely on economic signals to drive down emissions of carbon dioxide. That’s by design. Those signals — higher market prices of fossil fuels — are essential to solve or at least massively shrink the climate crisis. Without them, any climate policy, including the “investment” approach favored by WCV and other green groups opposing or abstaining on I-732, will fall woefully short.

Make no mistake, Carbon Washington, the upstart group that drafted Initiative 732 last year and obtained hundreds of thousands of qualifying signatures to put it on the Nov. 8 ballot, dearly wants society to invest in massive weatherization and solarization of buildings, remediation of polluted communities, better urban and suburban transit, and the like.

So do I. In fact, my other “day job,” aside from running the Carbon Tax Center, is mostly fighting for those very investments and policies in New York City, where I live and work.

Either Carbon Washington or I could have written the first part of WCV’s second bullet:

To reduce carbon emissions quickly, we must not only decrease our use of fossil fuels, we must also rapidly increase our use of clean energy, including solar and wind power and the electrification of transportation. This is the only way for us to transition to a low-carbon economy and significantly decrease our use of fossil fuels.

Well, that transition is precisely what carbon taxes can spark. Raising the prices that businesses and households alike face for coal, oil and gas and for the goods and services manufactured from them will accelerate the society-wide switch to clean energy. Conversely, without those higher fossil fuel prices, solar and wind and electric vehicles and transit will forever be competing with one hand tied behind their backs. Sure, they’ll advance, but not nearly fast and widely enough to push out fossil fuels on the scale our climate requires.

I readily admit — and I’ll wager that Carbon WA will admit as well — that by itself the I-732 carbon tax won’t effectuate that transition either. The tax level specified in the initiative, essentially $25/ton of CO2 after two years, then rising 3.5% a year above general inflation, is too low for that. But that too is by design: the USA’s first statewide carbon tax can’t be super-steep, else industry and agriculture could be hampered vis-à-vis neighboring states, a prospect that would forestall approval by either voters or the legislature.

Rather, the Washington carbon tax is intended as proof of concept. Once a carbon tax has been established in one state, it can be adopted by others, creating a critical mass of political acceptance, demonstrating success in driving down emissions, and disarming the negative arguments on effectiveness, equity and overall feasibility that have stood in the way of a national tax on carbon emissions.

Moreover, as I argued recently, the emerging possibility of a “wave” election transforming the power dynamics in Congress creates a surprise bonus opportunity, in which winning a carbon tax next month in just one state could give tremendous momentum to carbon tax proposals at the federal level.

Even without a Democratic takeover of one or both houses of Congress, the national and global perspective completely moots the insular one inherent in WCV’s complaint that I-732 “can’t ensure that we will achieve the pollution reductions that are required in state law.” Whether or not the particular carbon tax on the Nov. 8 state ballot lets Washington meet those targets is dwarfed by the potential of the carbon tax template to go viral nationally and internationally.

But perhaps the most telltale confusion in that first WCV bullet point is the charge that I-732 “allows all polluters to pay to continue to pollute instead of reducing emissions.” As the saying goes, that’s a feature of carbon-taxing, or indeed any carbon pricing system, not a bug.

Here’s the thing, or two things: first, in our society, polluters get to choose to pollute; what I-732 does is to finally make polluters pay to do so; second, polluters’ choices — and whether we like it or not, “polluters” means all of us who press a gas pedal or turn on a switch as well as the corporate bosses atop the system that limits our agency to choose — are affected by prices.

Every day, in Washington state alone, millions of decisions are made, some almost microscopic (how fast to accelerate up that hill; whether to drive to the nearby mall or the distant one) and some momentous (Boeing’s design and material selections for future aircraft; how it powers its factories) that together determine energy demand and fuel choice and, thus, carbon emissions.

As much as we might wish otherwise, we as a society can’t take away the freedom to make those choices. We can constrain some choices through regulations such as CAFÉ and appliance standards and building codes and the like. We can expand choice through judicious planning. But regulations and planning by their nature can only address one facet of the many-sided carbon equation. A carbon tax, in contrast, operates on every side. (For more on this point, please download and read our 2014 comments to the Senate Finance Committee on energy subsidies vs. taxes.)

We could conjure Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” if the right wing hadn’t co-opted it to prop up its laissez-faire ideology. Let’s say instead that the tax on carbon pollution embodied by I-732 is neither an upending of our market system nor the “clever tinkering with market forces” alleged by an environmental-justice opponent, but an overdue and essential correction — a way to enable markets to finally tell the truth about what fossil-fuel burning is doing to our climate.

The final point to address here is Washington Conservation Voters’ objection to I-732’s allocation of the carbon tax revenues:

Unfortunately, [I-]732 devotes the revenue created by the initiative on tax cuts, instead of strategically reinvesting in clean energy to accelerate our transition away from fossil fuels and fund an equitable transition for workers and disadvantaged communities.

True again, but just a sliver of the whole truth. “Tax cuts” conjures giveaways to the wealthy, but I-732 is the opposite. It applies most of the carbon tax revenues to cutting the state sales tax, a regressive tax like no other that for decades has slammed Washington’s poorest households and communities. The percentage point cut in that tax, to 5.5% from the current 6.5%, allows the carbon tax to yield a net financial gain for most families in the bottom half.

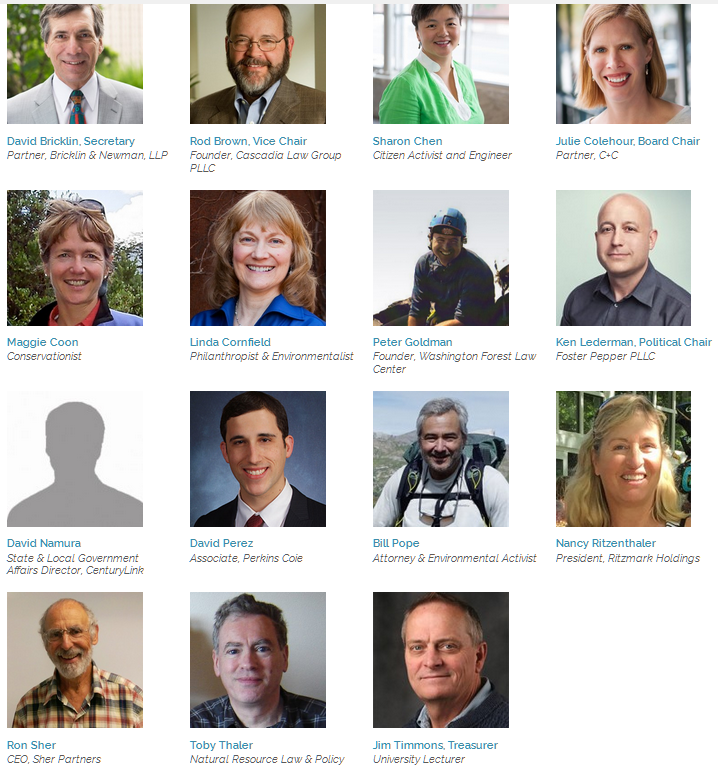

Do the trustees of Washington Conservation Voters fully grasp the game-changing potential of I-732?

Imagine if WCV had written the revenue-treatment provisions of I-732 to “reinvest [the carbon tax dollars] in clean energy” and “fund an equitable transition for workers and disadvantaged communities.” Without a doubt, the fossil fuel interests would have blasted the initiative for compounding the financial strains already faced by Washington low- and middle-income families . . . and they would have been right. Branded, correctly, as income-regressive, the carbon tax would have been consigned to a resounding defeat.

Making the carbon tax income-progressive, and not the shibboleth of “appealing to Republicans,” is the main reason Carbon Washington designed Initiative 732 to be revenue-neutral. But that decision has laid bare real fault lines in the environmental community, particularly on energy prices.

Green opponents of I-732 appear to believe that we — Washington, the United States, the world — can craft policies to quickly abandon carbon fuels without rapidly raising their market prices; or that the right energy-investment programs will offset the impacts of those price rises on vulnerable households and communities (a category that since the onset of the financial crisis has grown to encompass perhaps two-thirds of U.S. families).

Proponents believe, as I do, that rapidly raising the market prices of fossil fuels is essential, and that the only sure way to protect households and communities financially is to return the revenues in some progressive fashion. Nationally, that could be via the “dividend” approach propounded by Citizens Climate Lobby. That is probably not practicable for individual state carbon taxes, however, and I believe Carbon WA made the right call to swap out the revenue by cutting the sales tax.

In either case, the carbon reductions sacrificed by returning instead of investing revenue can be recouped by raising the carbon tax rate briskly year after year — a policy that can be enacted if and only if a clear majority of households are made better off or at least kept whole through revenue return.

In closing, let me affirm that I’m a man of the Left. Like Paul Goodman, whom I cited at the top, I’m suspicious of all powerful organizations, private or public. Nevertheless I firmly believe in the capacity of government to do good. If enough other citizens felt the same way, I might well be calling for the investment program that LCV says it wants. Heck, if a majority believed as I do, our country wouldn’t have one of the industrialized world’s most unequal distributions of income and wealth. Instead we would have a social system to support families that stood to lose more from rising fuel prices than they would gain from energy savings.

But we don’t live in that kind of society. We can fight for it, as I and many others in the climate movement do. But we can’t design climate policy for a society we don’t yet have. To turn away from the most potent climate policy instrument we have — one that is now, almost miraculously, being put before the voters of an entire state — would be sheer folly.

Click here for more on I-732, including links to the best and most recent press coverage.

The Political Meltdown That Could Save The Climate

Anyone with a lit screen knows by now that shell-shocked Republicans are abandoning the Trump ship in droves. As the exodus threatens to become a stampede, with a longtime GOP operative declaring that “The Republican Party is caught in a theater fire; people are just running to different exits as fast as they can,” talk of election “win probabilities” is pivoting from the presidential race to Congress.

A Trump collapse could give Democrats back the House,” reported Vox this weekend, citing analysis that a mere six-point Clinton plurality could swing the 31 needed seats in its wake. While that’s probably over-optimistic, a more decisive margin over Trump might do the trick.

The ramifications for climate could be huge: Democratic control of both the White House and Congress clears a path for a federal carbon tax without having to somehow vault over GOP denialists. Which could make next month’s ballot referendum in Washington state, Initiative 732, even more momentous. Enacting the country’s first carbon tax wouldn’t just produce a template for other states; it could spark national legislation establishing a U.S. tax on carbon emissions, perhaps as early as 2017.

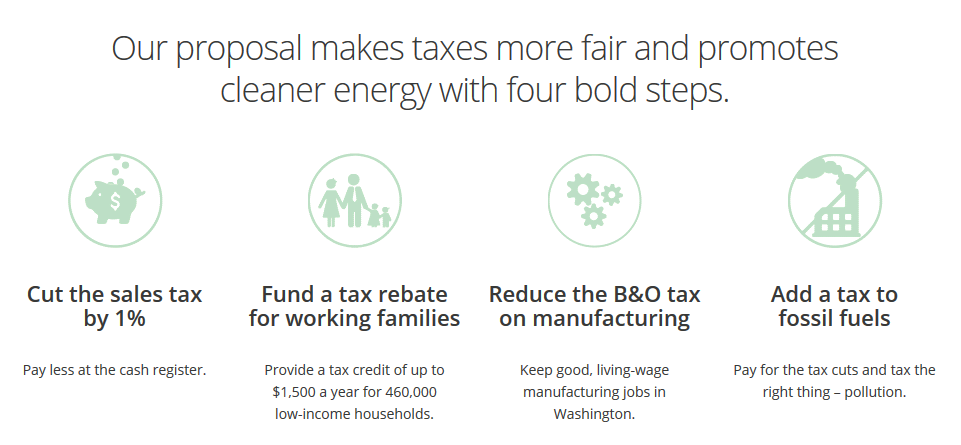

Infographic from Yeson732.org. The revenue-neutral carbon tax design has turned off some Washington-state climate advocates.

Let’s be clear: a U.S. carbon tax isn’t just helpful climate policy. It’s the core of any program for shrinking carbon emissions massively, relentlessly and globally. Only a briskly rising carbon tax rewards and thus bends every investment, decision and behavior toward less use of fossil fuels. Only a carbon tax can be replicated so the world’s nations can meet the commitments they made in Paris a year ago and ratified last month. And only a carbon tax produces revenues that can protect low- and middle-income families as fossil fuel prices rise — as they must to blow open the gates to the renewables-and-efficiency revolution at full scale.

The holistic power of carbon taxing is what motivated the grassroots organizers at an upstart group called Carbon Washington to crisscross the state last year and collect the 350,000 signatures that placed “I-732” on the Nov. 8 ballot. It’s also what makes it vexing that many green groups in the state have refrained from supporting I-732. Some are actively opposing it.

The schism has been covered widely (and insightfully) in recent weeks, most recently by Natasha Geiling in Think Progress. “Opposition to Washington’s historic carbon tax initiative is coming from the unlikeliest of sources,” reads her headline, which then asks, “It’s the only carbon tax on the ballot in the country. So why are some environmental groups fighting it?”

The answers are many. Carbon WA drew up I-732 without consulting fully with the entire spectrum of climate advocates. The design of its carbon tax is more attuned to the market than to government, with the carbon revenues “returned” to households (see graphic) rather than invested directly in clean energy and community remediation. And perhaps the in-state green groups are guided more by local and state concerns while Carbon WA set its sights nationally and globally.

Those points can be parsed endlessly. But the central fact for climate, which the Republican implosion is making more salient daily, is that the fissure in Washington state threatens to sink the initiative and botch our chance to put a carbon tax on the national legislative agenda starting months from now. Polling on I-732 suggests that a deficit in August may have flipped into a slight plus, but a fifth of voters are still undecided, and disunity among climate advocates makes it tougher to seal the deal.

There’s no second chance at this in the Evergreen State. Washington’s legislature has shown no appetite for a carbon tax, and a new referendum can’t get on the ballot until 2018. Organizing in other states has fallen short as well. Whether we like it or not – and the economist in me makes me a big fan – I-732 is the only game going.

The U.S. elections will doubtless take further twists in the final four weeks, but the possibility of debating and actually winning a national carbon tax is suddenly, miraculously upon us. The referendum in Washington state is going to function as the first big test. Whatever its imperfections, the climate movement’s greatest imperative must be to come together and pass I-732.

There is no hiding from climate change. It is real and it is everywhere. We cannot undo the last 10 years of inaction. What we can do is make a real and honest effort—today and every day—to protect the health of our environment, and with it, the health of all Canadians.”

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, in his Oct 3 address to Parliament in which he proposed a national carbon tax to start in 2018, quoted in Associated Press story posted later that day by Rob Gillies, Trudeau says Canada to implement carbon tax.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- …

- 170

- Next Page »