Nov. 2 addendum: Read Musk’s carbon tax pitch, transcribed from Leonardo DiCaprio’s new climate change documentry, Before The Flood, at bottom.

Visionary inventor-entrepreneur Elon Musk is constantly in motion. Last week he was in Nevada checking on his Gigafactory, which purportedly will be the world’s largest-footprint building (as big as 107 football fields) and make enough batteries each year to power 1.5 million Tesla Model 3s. Yesterday Musk revealed his intention to merge Tesla Motors and SolarCity — a $2.6 billion wager that Tesla owners will use those batteries to store power from SolarCity panels.

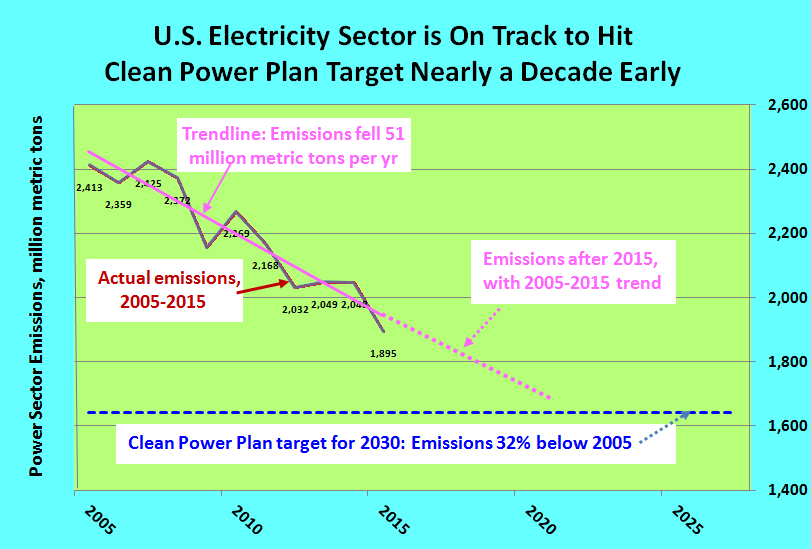

This is big business, big climate and big vision rolled into one. Large-scale deployment of batteries could let solar and wind resources dominate electricity production without need for carbon-emitting grid support by fossil fuel plants. Replacing gasoline-powered autos with electrics will almost certainly squeeze carbon emissions out of transportation faster than biofuels or other low-carbon liquid fuels.

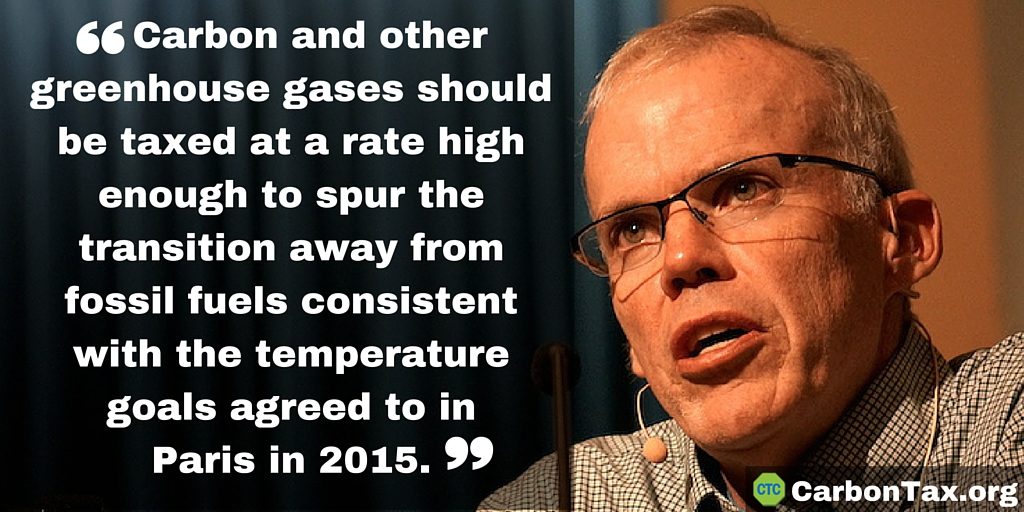

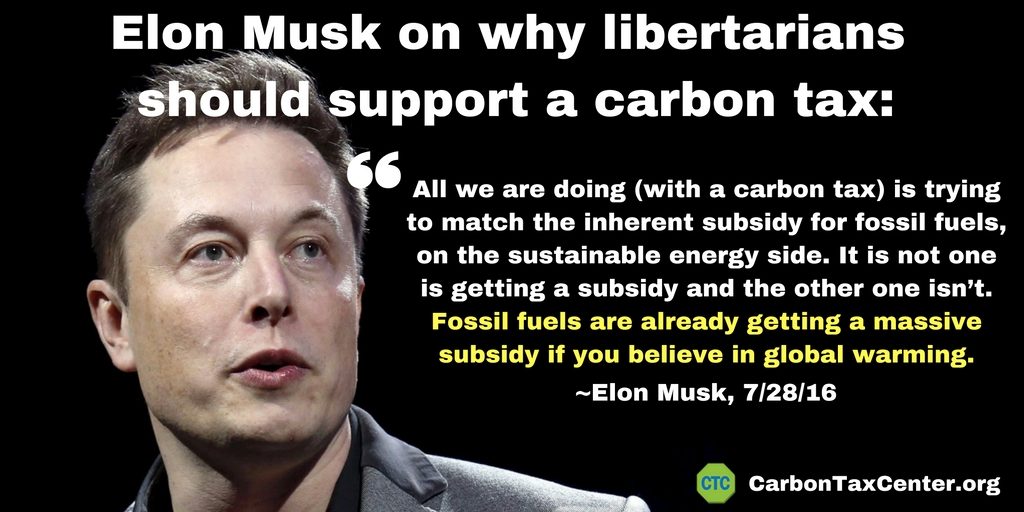

In Nevada, Musk also spoke up for carbon taxes, though hardly for the first time. Four years ago, for example, at the Wall Street Journal’s ECO:nomics conference in Santa Barbara, CA, Musk disparaged tax credits for green cars and declared that “the best method for addressing climate change in the automotive industry is to impose a tax on carbon dioxide emissions,” according to the trade journal plugincars. But what he said last week was so richly detailed and articulated that it deserves to be quoted in full.

In Nevada, Musk also spoke up for carbon taxes, though hardly for the first time. Four years ago, for example, at the Wall Street Journal’s ECO:nomics conference in Santa Barbara, CA, Musk disparaged tax credits for green cars and declared that “the best method for addressing climate change in the automotive industry is to impose a tax on carbon dioxide emissions,” according to the trade journal plugincars. But what he said last week was so richly detailed and articulated that it deserves to be quoted in full.

As reported by Benjamin Spillman in the Reno Gazette-Journal, Musk was asked whether the Gigafactory would have been economically viable without over a billion dollars in state incentives, plus federal tax credits for electric vehicles and solar panels. He replied:

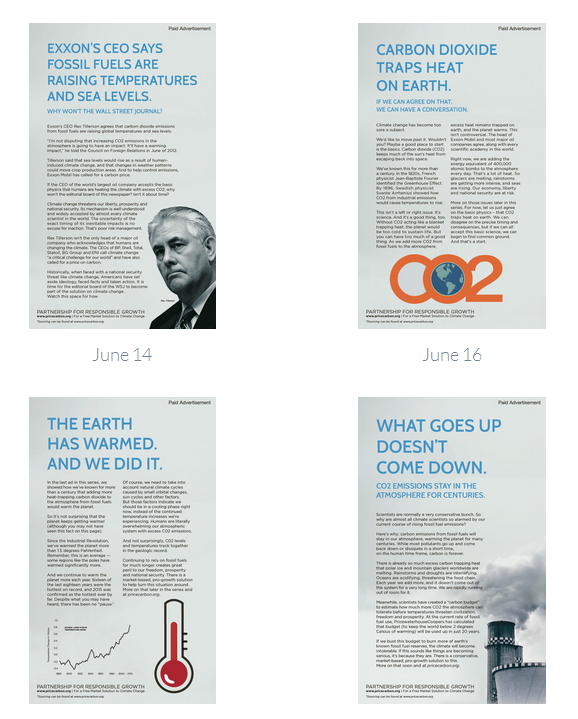

[I]f you accept the scientific consensus[,] every oil burning activity is subsidized, dramatically. If you believe there is a value to the CO2 capacity of the atmosphere and oceans and that CO2 capacity is not being paid for by the price at the gas pump or the coal that is being burned for electricity generation or whatever its use may be then every single fossil fuel burning activity is massively subsidized.

After reminding his Nevada audience that climate change “has become sort of an ideological issue because there are people who think that global warming is not true,” Musk continued:

[A]ll we are doing [with a carbon tax] is trying to match the inherent subsidy for fossil fuels . . . on the sustainable energy side. Fossil fuels are already getting a massive subsidy if you believe in global warming. If you don’t then [the subsidy] seems really unfair. If you do then it is like oh we are just trying to correct it.

But Musk was just warming up to the carbon taxing subject:

The real right way to correct [the subsidy] would be to establish a carbon tax. If you ask any economist they will tell you that is the obvious thing to do, put the correct price on carbon because we currently have an error in the economy which misprices carbon at zero or something closer to zero. It is a fundamental economic error.

He then turned to the supposed conflict between libertarian ideology and taxation:

For people that have a sort of libertarian bent they get a little confused. . . They need to appreciate the high level principle of why they are opposed to government intervention. They are actually opposed to government intervention because it causes false pricing. If the government says we are going to massively incent the production of corn, so that effectively corn gets mispriced and we make too much corn, that . . . does not benefit the country if you make too much of something because of a government driven pricing error . . . That is sort of what people with a libertarian bent are opposed to.

However if you have . . . an unpriced externality [with] the CO2 capacity of the oceans and atmosphere priced very close to zero then any government action to increase the price above zero reduces the error in the economy. [What libertarians] should actually be opposed to is anything that increases the error in the economy, a pricing information error. So pricing carbon, if you believe in global warming, does not increase the price of the error it decreases the price of the error.

Spillman tweeted these remarks, and Musk retweeted his approval:

The libertarian argument for a carbon tax https://t.co/WmbGp2YuUO

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) July 29, 2016

Whether or not you identify as libertarian, you should savor Musk’s bracing clarity on (and for) carbon taxing. Maybe in time, other solar and wind advocates will bolster their customary pleading for subsidies with their own clarion call for carbon taxing.

Addendum, Nov. 2, 2016: Musk did a star turn in support of carbon taxes in the Leonardo DiCaprio climate docu, Before The Flood. This transcript is courtesy of EcoWatch. The film is up on YouTube through Nov. 6. Afterwards, only in theaters.

DiCaprio is in the Nevadan desert visiting the “gigafactory,” the latest project of Tesla founder Elon Musk. Once at full operation by 2020, the vast factory aims to be producing annually 500,000 electric vehicles and batteries/cells equal to 85 GWh/yr. Musk explains why this could be a game-changer:

Elon Musk: What would it take to transition the whole world to sustainable energy? What kind of throughput would you actually need? You need a hundred gigafactories.

Leonardo DiCaprio: A hundred of these?

Elon Musk: A hundred. Yes.

Leonardo DiCaprio: That would make the United States…

Elon Musk: No, the whole world.

Leonardo DiCaprio: The whole world?!

Elon Musk: The whole world.

Leonardo DiCaprio: That’s it?! That sounds manageable.

Elon Musk: If all the big companies do this then we can accelerate the transition and if governments can set the rules in favour of sustainable energy, then we can get there really quickly. But it’s really fundamental: unless they put a price on carbon…

Leonardo DiCaprio: … Then we are never going to be able to make the transition in time, right?

Elon Musk: Only way to do that is through a carbon tax.