Here we reprint a letter published in the Financial Times on April 25 by noted environmental economist Thomas Sterner. Link was added by CTC. Text and headline are unchanged.

Last week, representatives of more than 130 nations, including French President François Hollande, signed the climate pact in New York. The agreement is a success because it has widespread support but it contains little of substance on instruments.

Elinor Ostrom, the economist and Nobel laureate, insisted that the most difficult part of a negotiation is to get the participants to the table. Paris did that. Now every country must ratify, but that is still just the start. To end the fossil fuel era within a generation we need our very best instruments, and yes, that does mean a carbon tax. This is all the more urgent because of current low prices.

Prof. Thomas Sterner

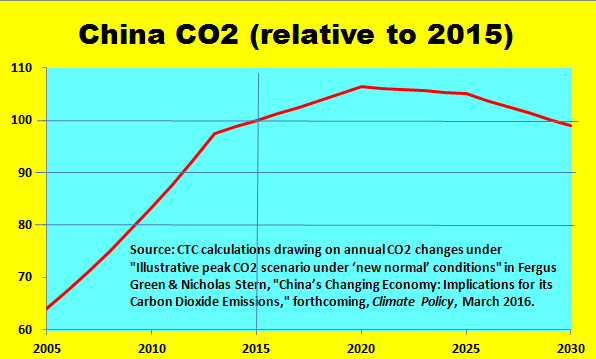

The fossil fuel industries are not going to give up voluntarily — they will fight back. The recent fall in oil prices from $140 to $30/bbl will provide impetus for increased consumption and emissions may soon rise again. The price fall is partly the result of expectations of stricter climate policies. Fossil producers have understood that, come 2030, business will not be good — so they have done everything in their power to maximise capacity and sell now.

The Saudis have realised that their old strategy of defending OPEC in order to control the oil market in the very long run will not work in the face of climate realities. This is an example of the “green paradox.” Expectations of future taxation lower current prices. The green paradox has already happened in a big way and cannot really happen again (fossil fuel prices cannot fall much more).

We, the consuming importers, would be stupid if we did not seize the opportunity to tax fossil fuels now. This is the best way of stimulating efficiency and renewables — it also gives money to the Treasury (instead of to the producers), and it helps keep the fossil rents low — making it easier to close mines and oilfields.

Thomas Sterner

Professor of Environmental Economics

Gothenburg, Sweden and Collège de France, Paris

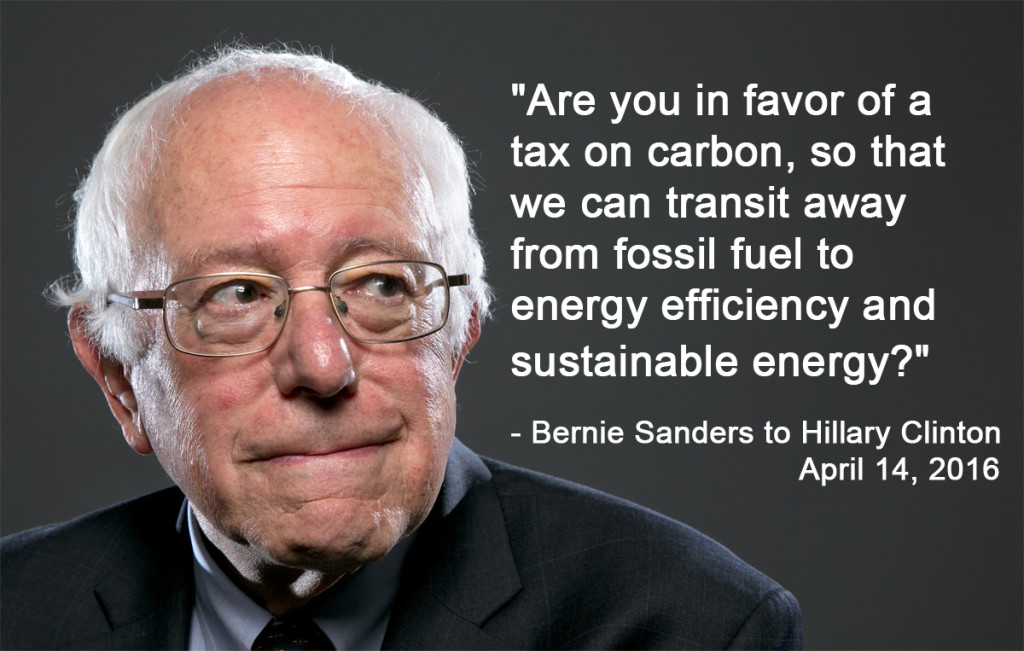

Not right now. Not on climate change. Now, the truth is, we have got to tell the fossil fuel industry that their short-term profits are not more important than the future of this planet. And that means — and I would ask you to respond. Are you in favor of a tax on carbon so that we can transit away from fossil fuel to energy efficiency and sustainable energy at the level and speed we need to do?

Not right now. Not on climate change. Now, the truth is, we have got to tell the fossil fuel industry that their short-term profits are not more important than the future of this planet. And that means — and I would ask you to respond. Are you in favor of a tax on carbon so that we can transit away from fossil fuel to energy efficiency and sustainable energy at the level and speed we need to do?

Leaving aside the fact that the global renewables revolution already has a leader (hint: it’s Europe’s

Leaving aside the fact that the global renewables revolution already has a leader (hint: it’s Europe’s