Gavin A. Schmidt, head of NASA’s climate-science unit (the Goddard Institute for Space Studies), in 2015 Was Hottest Year in Historical Record, Scientists Say, NY Times, Jan. 21.

Just How Scary Is 2015’s Temperature Record? We Count the Ways.

Even for folks hardened by decades in the trenches fighting climate change, the release yesterday of 2015 planetary temperature data was still shocking. The “global land and water temperature” didn’t just set another record last year, it changed the rate at which those records are being set.

This morning we downloaded the official NOAA/NCDC global temperature dataset of temperature anomalies — that’s each year’s deviation from the trend increase averaged across the 20th Century. Here’s what we saw when we ran the stats:

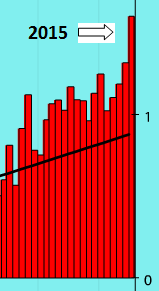

- The 2015 anomaly was 0.90 degrees Celsius (1.6 degrees Fahrenheit; except for graph excerpt at right, all figures here are Celsius); in other words, last year’s global average temperature was almost a full degree above the 20th Century average.

- The 2015 temperature anomaly was 0.16 degrees greater than the anomaly for 2014, making last year’s increase the biggest since 1997 — even though the 2014 anomaly had just set a new record.

- The trendline we drew through 1975-2015 temperature data has a nearly 4 percent steeper slope than our year-earlier trendline for 1975-2014 data. Adding 2015 data in effect lifts the prior trend from its moorings, like an earthquake, tilting it upward.

Here’s how climate scientist Michael Mann characterized the new data, as reported by the New York Times:

Michael E. Mann, a climate scientist at Pennsylvania State University, calculated that if the global climate were not warming, the odds of setting two back-to-back record years would be remote, about one chance in every 1,500 pairs of years. Given the reality that the planet is warming, the odds become far higher, about one chance in 10, according to Dr. Mann’s calculations.

(The entire Times article, which led the paper’s Jan. 21 print edition and was written by the paper’s superb climate reporter, Justin Gillis, is well worth reading.)

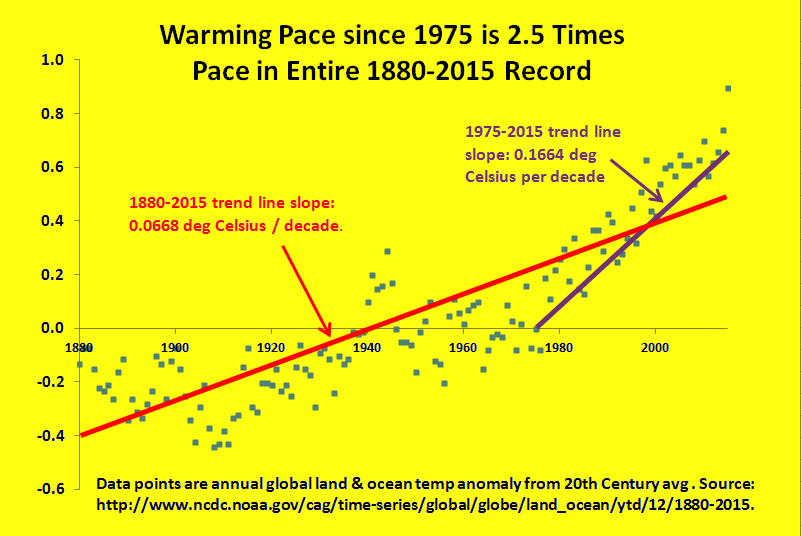

Here’s one more way of grasping how the rate of temperature rise is accelerating:

The trendline running through the entire 1880-2015 NOAA/NCDC dataset yields an average rate of temperature rise of 0.0668 degrees per decade; it’s probably easier to multiply that by 10 to derive a per-century rise of two-thirds of one degree. However, a trendline on just the most recent 40 years, 1975-2015, gives an average rise of 0.1664 degrees per decade, or one-and-two-thirds of one degree per century. Over the past 40 years, temperatures have risen 2.5 times as fast as they have over the entire 135-year record.

(NB: Our 1880-2015 slope matches the slope reported by NOAA/NCDC. Our choice of 1975 as the start year for our recent trendline has no particular significance; a regression on 1995-2015 yields a similar slope. For those interested in methodological issues in temperature measuring, the Niskanen Institute posted a useful primer earlier this week.)

In his State of the Union Address last week, President Obama sent a message to senators and representatives on the GOP side of the aisle:

[I]f anybody still wants to dispute the science around climate change, have at it. You will be pretty lonely, because you’ll be debating our military, most of America’s business leaders, the majority of the American people, almost the entire scientific community, and 200 nations around the world who agree it’s a problem and intend to solve it.

It’s hard to discern the extent to which the denialism running through the Republican Party is driven by ideology or by politics, especially since the two are strongly intertwined. At some point, reality will come into play. Temperature data can help that happen. So can election returns.

Putting a solid price on carbon pollution, as Carbon Washington’s I-732 does, would massively accelerate the shift to clean energy.”

Jigar Shah, co-founder and president of Generate Capital and founding CEO of SunEdison, in Duncan Clauson, Endorsement From Jigar Shah, as reported by Carbon Washington, Jan. 5.

British Columbia’s Carbon Tax: By the Numbers

British Columbia, Canada’s third-most populous province, began taxing carbon dioxide and other greenhouse-gas emissions from combustion of fossil fuels nearly seven and a half years ago, pursuant to the province’s Carbon Tax Act. The province-wide tax commenced on July 1, 2008 at a level of $10 (Canadian) per metric ton (“tonne”) of CO2 and increased by $5 per tonne in each of the next four years, reaching its current level, $30/tonne, in July 2012.

The point of the tax is to reduce emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. It is therefore surprising that very little detailed quantitative analysis of the tax’s efficacy in reducing emissions has appeared to date. Answers haven’t been readily available to fundamental questions such as: Have British Columbia emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas actually fallen? If they have, by how much? How have the reductions in BC emissions stacked up against the rest of Canada, which does not tax carbon emissions (save for modest taxes in Alberta and Quebec)? How does the recent trajectory of British Columbia emissions compare to that prior to the onset of the tax? Which sectors have shown the biggest, or the smallest, declines?

The Carbon Tax Center searched for answers to these questions during 2015. Not finding definitive data, we set out to develop our own. The result is a new report, British Columbia’s Carbon Tax: By the Numbers, which available here. A spreadsheet with supporting data is available here.

BC’s carbon tax is both the most comprehensive and transparent carbon tax in the Western Hemisphere, if not the world. A recent assessment by two leading environmental economists stated that “British Columbia has given the world perhaps the closest example of an economist’s textbook prescription for the use of a carbon tax to reduce [greenhouse gas] emissions.”

Moreover, the BC tax is gaining adherents. On the eve of the Paris climate summit, in November 2015, Alberta Premier Rachel Notley committed to a similar carbon tax. Alberta’s tax will begin in 2017 at $20 per metric ton and rise in 2018 to $30, matching the current level in British Columbia. Although Canada’s two most populous provinces, Ontario and Quebec, are moving toward carbon cap-and-trade systems, the new Trudeau administration in Ottawa could choose to fashion a national carbon tax from British Columbia’s, with the possibility of higher tax levels to evoke larger emission reductions.

Executive Summary and Key Findings

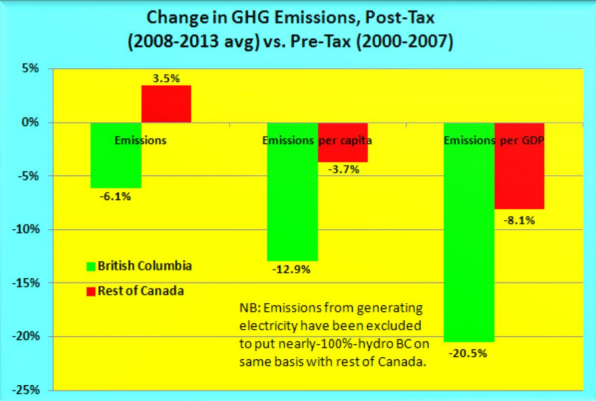

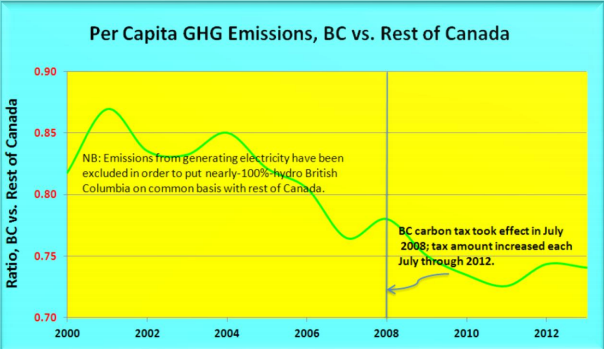

British Columbia introduced a carbon tax in 2008. Since then, per capita emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases covered by the tax have declined, continuing a downward trend that began in 2004. Averaged across the period with the tax (2008 through 2013; no data are available for 2014), province-wide per capita emissions from fossil fuel combustion covered by the tax were nearly 13 percent below the average in the pre-tax period under examination (2000-2007).

The 12.9% decrease in British Columbia’s per capita emissions in 2008-2013 compared to 2000-2007 was three-and-a-half times as pronounced as the 3.7% per capita decline for the rest of Canada. This suggests that the carbon tax caused emissions in the province to be appreciably less than they would have been, without the carbon tax.

To allow comparability, the above figures are per capita. They also exclude emissions from electricity production ― a minor emissions category for British Columbia, which draws most of its electricity from abundant (and zero-carbon) hydro-electricity, but a major emissions source for much of Canada. On a total emissions basis (not per capita), British Columbia emissions of CO2 and other GHGs covered by the carbon tax but excluding the electricity sector averaged 6.1% less in 2008-2013 than in 2000-2007. (The reduction was 6.7% when electricity emissions are counted.) The 6.1% contraction is roughly what would be expected from a small carbon tax such as British Columbia’s. (See sidebar on page 5.)

The carbon tax does not appear to have impeded overall economic activity in British Columbia. Although GDP in British Columbia grew more slowly during 2008-2013, the period with the carbon tax, than in 2000-2007, the same was true for the rest of Canada. From 2008 to 2013, GDP growth in British Columbia slightly outpaced growth in the rest of the country, with a compound annual average of 1.55% per year in British Columbia, vs. 1.48% outside of the province.

GHG emissions increased in British Columbia in 2012 and again in 2013, not just in absolute terms but also per capita. This suggests that the carbon tax needs to resume its annual increments (the last increase was in 2012; its bite has since been eroded by inflation) if emissions are to begin again their downward track.

Click here to read the full report.

Meet the New Climate Villain: Cheap Oil

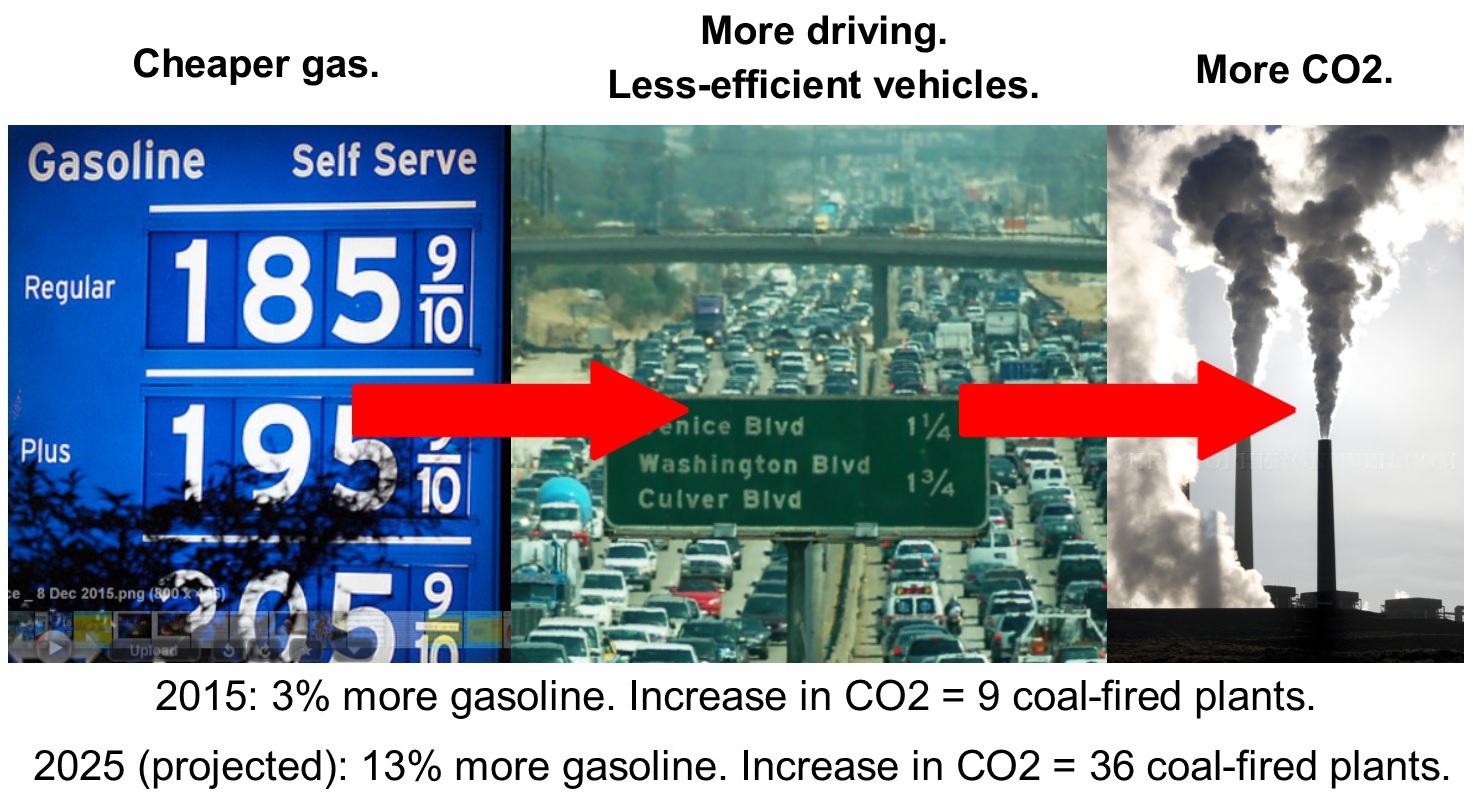

Paris climate negotiators wrangling over global temperature goals might want to spend a moment pondering cheap gasoline.

Fact: after years of steady gains, average gas mileage of new vehicle purchases in the U.S. is down almost a mile per gallon this year, according to data from the University of Michigan’s Transportation Research Institute.

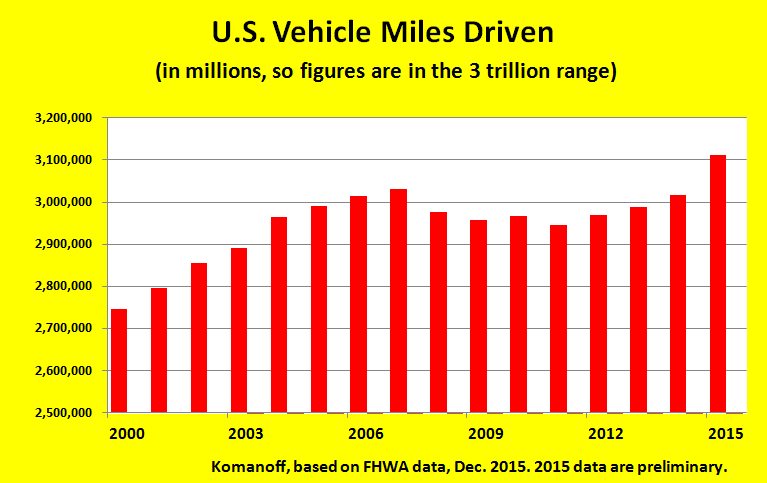

Fact: Through September, total miles driven in the U.S. this year are up 3.5 percent ― the largest increase in decades.

One thing is driving both trends: cheap gasoline. The average price of gas sold in the U.S. over the past ten months is 25 percent below last year’s price — the steepest drop in at least 70 years. Americans are responding by driving more and dumping sedans for SUV’s and pickups.

Gasoline consumption is on track to rise nearly 3 percent this year. The additional carbon dioxide will be the equivalent of a full year’s emissions from nine coal-fired power plants. (My yardstick is 600 megawatts per plant, operating at 70% capacity factor. See note at end of post for link to calculations.) And that doesn’t count the substantial “upstream” emissions from refining crude oil into gasoline.

Gasoline consumption is on track to rise nearly 3 percent this year. The additional carbon dioxide will be the equivalent of a full year’s emissions from nine coal-fired power plants. (My yardstick is 600 megawatts per plant, operating at 70% capacity factor. See note at end of post for link to calculations.) And that doesn’t count the substantial “upstream” emissions from refining crude oil into gasoline.

Or, if you prefer, the likely 2015 increase in U.S. CO2 emissions caused by cheap gasoline, an estimated 30-35 million metric tons, will equal the entire annual emissions from burning all fossil fuels for all purposes from Ecuador . . . or Denmark . . . or Ireland . . . or Switzerland (take your pick). [Figures are here; multiply by 44/12 to convert from C to CO2.]

Can we be sure this year’s increase in gasoline use is entirely due to the drop in price? Not completely. But the inference is strong.

First, gasoline usage is at least mildly price-sensitive. Based on gasoline’s long-run price-elasticity, a 25 percent drop in price would touch off a roughly 10 percent increase in usage. The entire jump in demand wouldn’t be seen overnight, of course; it would take a decade or so for the lower price to work its way through car buyers’ purchase decisions (as well as manufacturers’ design choices). The 3 percent uptick this year is in line with what one would expect in the initial year.

Second, U.S. gasoline consumption stayed within a fairly narrow band from 2008 to 2014. Prices at the pump held steady as well, except during the worst of the great recession. What’s different this year is the plunge in price.

This year’s jump in CO2 emissions is bad enough. What’s really worrisome is that cheap oil — hence, cheap gasoline — is going to be with us for awhile. So say the experts who prepare the government’s Annual Energy Outlook forecast. I recently compared the 2025 forecast gasoline price between the 2012 AEO, which preceded the price collapse, and the 2015 AEO, which reflects it. Correcting for inflation, the government is projecting a 29 percent lower price of gas in 2025 than it projected three years ago.

When you run the lower price forecast through the price-elasticity for gasoline, you get this startling projection: in 2025, U.S. motorists will buy — and burn — nearly 13 percent more gasoline than would have been expected under the earlier (higher) price forecast. The associated increase in U.S. CO2 emissions in 2025 because gas will be cheaper is going to be huge: it equates to the annual output of 36 coal-fired power plants.

But let’s not stop there. Cheaper crude oil is bringing not just cheaper gas but cheaper diesel and cheaper jet fuel. I’ve run the reduced 2025 AEO price forecasts for all petroleum products through their respective price-elasticities, and the result is truly scary: Compared to projected 2025 emissions with the pre-plunge price trajectory, lower petroleum prices will result in 450 million metric tons of additional U.S. CO2 emissions in that year.

The increase will equal 8-9 percent of today’s U.S. CO2 emissions from all fossil-fuel burning. It will undo nearly all of the vaunted reductions in U.S. emissions since 2005. It will be the emissions equivalent of 100 additional coal-fired power plants. And that’s just for the U.S.

The antidote, of course, is a carbon tax — either a straight-up carbon tax or a hybrid one that surcharges petroleum products. A surcharge would reflect non-climate harms from oil consumption like traffic congestion, also place a charge on oil revenues’ corruption of governance in the U.S. and the Middle East.

Former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers wrote last January that cheap oil created a political opportunity for a carbon tax. We followed that here with First Tax Oil, Then Carbon. But to our knowledge no one has quantified how dire the need is — until now.

Cheap oil will make a mockery of just about every scenario to move the U.S. and other countries decisively off carbon fuels. Except scenarios based on carbon taxes.

Note: Calculations of increased oil consumption, resulting increase in CO2 emissions, and coal-plant equivalents, may be found in CTC’s carbon-tax spreadsheet model (Excel file).

A Call to Paris Climate Negotiators: Tax Carbon.

On Sunday, November 29, the eve of the UN climate summit in Paris, the Carbon Tax Center released a letter signed by 32 notable individuals urging Paris climate negotiators to focus on national carbon taxes, both for their intrinsic value and as a gateway to a global carbon price.

On Sunday, November 29, the eve of the UN climate summit in Paris, the Carbon Tax Center released a letter signed by 32 notable individuals urging Paris climate negotiators to focus on national carbon taxes, both for their intrinsic value and as a gateway to a global carbon price.

The group includes four Nobel Laureates, three former U.S. cabinet secretaries who served under four Presidents (from both major political parties), two former vice-chairs of the Federal Reserve System’s board of governors, and three distinguished faculty members from Harvard University’s economics department. It also includes leading carbon tax advocates from across the political spectrum: Jerry Taylor of the Niskanen Center, Mark Reynolds of Citizens Climate Lobby, and Charles Komanoff of CTC.

The text of the letter is directly below, followed by a complete listing of the signatories. (The identical text and listing are in this pdf.)

Released in Paris and New York, Sunday, November 29, 2015

Taxing carbon pollution will spur everyone ― businesses, consumers and policymakers ― to reduce climate-damaging emissions, invest in efficient energy systems and develop low-carbon energy sources.

This single policy change — explicitly using prices within existing markets to shift investment and behavior across all sectors — offers greater potential to combat global warming than any other policy, with minimal regulatory and enforcement costs.

We urge negotiators at the upcoming UN Climate Conference in Paris to pursue widespread implementation of national taxes on climate-damaging emissions.

We endorse these four principles for taxing carbon to fight climate change without undermining economic prosperity:

1. Carbon emissions should be taxed across fossil fuels in proportion to carbon content, with the tax imposed “upstream” in the distribution chain.

2. Carbon taxes should start low so individuals and institutions have time to adjust, but then rise substantially and briskly on a pre-set trajectory that imparts stable expectations to investors, consumers and governments.

3. Some carbon tax revenue should be used to offset unfair burdens to lower-income households.

4. Subsidies that reward extraction and use of carbon-intensive energy sources should be eliminated.

Signed,

|

|

|

(Institutional affiliations are for identification purposes only, and do not connote any organizational approval.)

Frank Ackerman, PhD

Principal Economist, Synapse Energy Economics

Kenneth J. Arrow, PhD

Nobel Prize in Economics, 1972

Joan Kenney Professor of Economics and Professor of Operations Research, Emeritus, Stanford University

Convening Lead Author, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Jim Barrett, PhD

Chief Economist, American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy

Former Senior Economist, Joint Economic Committee

Alan S. Blinder, PhD

Gordon S. Rentschler Memorial Professor of Economics and Public Affairs, Princeton University

Vice Chairman, Board of Governors, Federal Reserve System, 1994-1996

Member, President’s Council of Economic Advisers, 1993-1994

Dallas Burtraw, PhD

Darius Gaskins Senior Fellow, Resources for the Future

Steven Chu, PhD

Nobel Prize in Physics, 1997

U.S. Secretary of Energy, 2009-2013

Elected to Royal Society, 2014

William R. Keenan, Jr. Professor of Physics, Professor of Molecular and Cellular Physiology, Stanford University

Richard N. Cooper, PhD

Maurits C. Boas Professor of International Economics, Harvard University

Deputy Assistant Secretary of State, 1977-1981

Former Senior Staff Economist, Council of Economic Advisers

Robert H. Frank, PhD

Henrietta Johnson Louis Professor of Management, Cornell University

Professor of Economics, Samuel Curtis Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University

Shi-Ling Hsu, PhD

John W. Larson Professor of Law and Associate Dean, Florida State University College of Law

Charles Komanoff

Director, Carbon Tax Center

Gregory Mankiw, PhD

Robert M. Beren Professor of Economics, Harvard University

Chair, President’s Council of Economic Advisers, 2003-2005

Donald B. Marron Jr., PhD

Director of Economic Policy Initiatives, Urban Institute

Member, President’s Council of Economic Advisers, 2008-2009

Congressional Budget Office, Deputy Director 2005-2007, Acting Director 2006

Aparna Mathur, PhD

Resident Scholar in Economic Policy Studies, American Enterprise Institute

Warwick McKibbin, PhD

Non-resident Senior Fellow, The Brookings Institution

Professor of Economics, Australian National University and Centre for Applied Macroeconomic Analysis

Gilbert Metcalf, PhD

Professor of Economics, Tufts University

Deputy Assistant Treasury Secretary for Environment and Energy, 2011-2012

Adele C. Morris, PhD

Senior Fellow and Policy Director, Climate and Energy Economics, The Brookings Institution

Robert Reich, PhD

U.S. Secretary of Labor, 1993-1997

Chancellor’s Professor of Public Policy, Goldman School of Public Policy, University of California, Berkeley

John Reilly, PhD

Co-Director, MIT Joint Program on Science and Policy of Global Change

Senior Lecturer, MIT Sloan School of Management

Mark Reynolds

Executive Director, Citizens Climate Lobby

Alice M. Rivlin, PhD

Senior Fellow, The Brookings Institution

Visiting Professor, Georgetown University

Vice Chair, Board of Governors, Federal Reserve System, 1996-1999

Director, White House Office of Management and Budget, 1994-1996

Founding Director, Congressional Budget Office, 1975-1983

James Rydge, PhD

Lead Economist, Global Commission on Economy and Climate, New Climate Economy

Thomas C. Schelling, PhD

Nobel Prize in Economics, 2005

Lucius N. Littauer Professor of Political Economy, Harvard University (Emeritus)

Professor of Foreign Policy, National Security, Nuclear Strategy and Arms Control, School of Public Policy, University of Maryland

Robert J. Shapiro, PhD

Chairman, Sonecon

Under Secretary of Commerce for Economic Affairs 1997-2001

Senior Fellow, Georgetown University School of Business

George P. Shultz, PhD

Thomas W. and Susan B. Ford Distinguished Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University

Secretary of State, 1982-1989

Secretary of the Treasury, 1972-1974

Director, White House Office of Management and Budget, 1970-1972

Secretary of Labor, 1969-1970

Joseph Stiglitz, PhD

Nobel Prize in Economics, 2001

Elected to Royal Society, 2001

John Bates Clark Medal, 1979

Professor of Economics, Columbia University

Former Senior Vice President and Chief Economist, World Bank

Chair, President’s Council of Economic Advisers, 1995-1997

Steven Stoft, PhD

Convenor, Global Carbon Pricing Symposium, Economics of Energy & Environmental Policy

Founder and Director, Global Energy Policy Center

Chad Stone, PhD

Chief Economist, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

Council of Economic Advisers, Chief Economist 1999-2000, Senior Economist 1996-1998

Jerry Taylor

President and Founder, Niskanen Center

Vice President, Emeritus, Cato Institute

Task Force Director Emeritus for Energy, Environment and Natural Resources, American Legislative Exchange Council

Richard Thaler, PhD

Ralph and Dorothy Keller Distinguished Service Professor of Behavioral Science and Economics, Booth School of Business, University of Chicago

Eric Toder, PhD

Institute Fellow, Urban Institute

Co-director, Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center

Martin Weitzman, PhD

Ernest E. Monrad Professor of Economics, Harvard University

Gary Yohe, PhD

Huffington Professor of Economics and Environmental Studies, Wesleyan University

Senior Member, UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

(Institutional affiliations are for identification purposes only, and do not connote any organizational approval.)

Here’s What’s Next After Stopping Keystone XL

Fantastic news! This morning President Obama rejected the Keystone XL pipeline, capping a seven-year uprising against the project, which would have carried 800,000 barrels of extreme oil from Canada to the Gulf Coast every day.

All of us concerned with climate have reason to celebrate. This victory was hard fought, and it shows the growing power of the climate movement.

All of us concerned with climate have reason to celebrate. This victory was hard fought, and it shows the growing power of the climate movement.

But as I read the New York Times front page story about the big news, a buried quote caught my attention. Energy market analyst Christine Tezak told the Times, “From a market perspective, the industry can find a different way to move that oil … How long it takes is just a result of oil prices. If prices go up, companies will get the oil out.”

I don’t often find myself agreeing with energy market analysts, but Ms. Tezak’s comments underscore the reality that a carbon tax that builds fossil fuels’ true costs into their price is the only lasting way to address climate change and keep those fuels in the ground.

The climate movement has scored a huge win today, and we tip our hat to Bill McKibben and 350.org for helping build the movement around stopping Keystone. It was a gutsy choice against huge odds, and they stuck to it. But we need the victory to be more than symbolic, and more than a show of force. We need it to be a stepping-stone to permanence.

We at CTC will be continuing to offer hard-hitting news and analysis to educate leaders in the climate movement about the urgent need to prioritize a carbon tax in their — and our — campaigning.

If you agree, please take a moment to retweet this image and help spread the word.

The evidence suggests that voters are more open to carbon taxation than the present Republican position that climate change is no big deal and requires little federal response.”

Niskanen Institute president Jerry Taylor, in “Ed Gillespie Is Dead-Wrong About Carbon Taxes,” Nov. 2.

It is just the right moment to introduce carbon taxes.”

Christine Lagarde, Managing Director, International Monetary Fund, quoted in Global Post, Oct. 7.

Pope Francis’s Embrace of Our Environment: Live-Tweeting at the U.N.

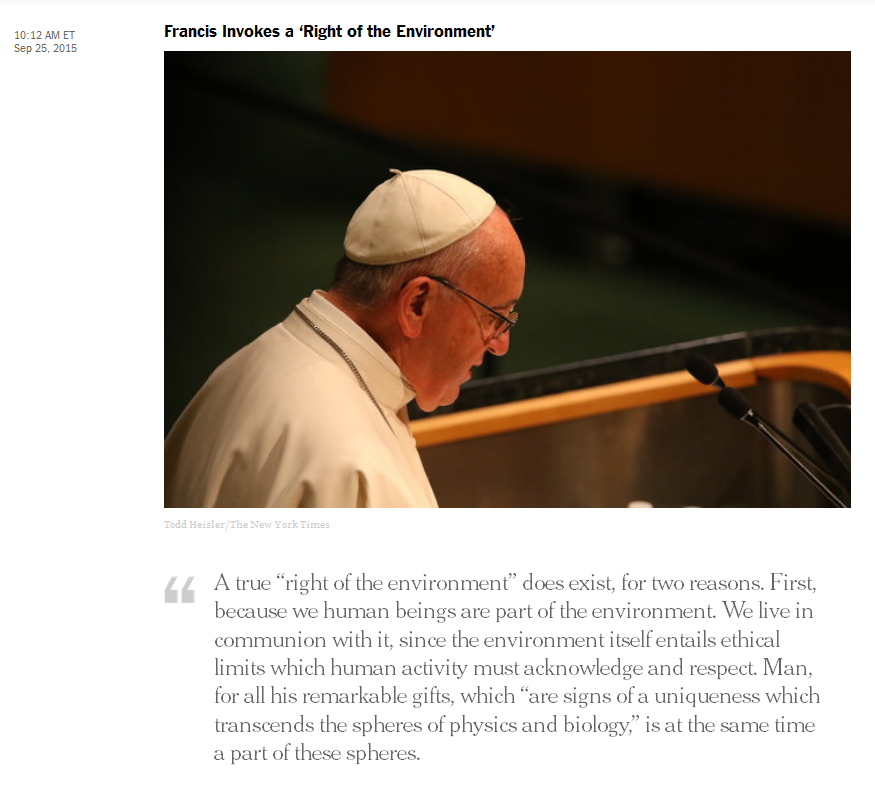

The following passages, transmitted by the New York Times via Twitter (@nytimes), capture Pope Francis’s call this morning to world leaders and humanity to place ourselves within, not above, the natural world; to care for Earth rather than destroy it; and to recognize for all living things a “Right of the Environment.”

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- …

- 170

- Next Page »