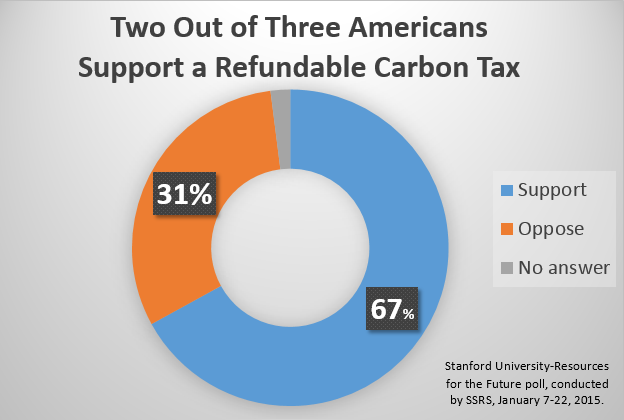

For more years than I care to count, the Carbon Tax Center beseeched pollsters to take Americans’ temperature on revenue-neutral carbon taxes. Time and again we explained that polling about carbon taxes had to incorporate the option of returning revenues to households ― as most carbon tax bills would do. Otherwise, the tax came off as all stick and no carrot, and about as appealing to most folks as a cold shower.

Finally, a Stanford University-Resources for the Future poll asked that question. The results, released today, show that two-thirds of Americans support making corporations pay a price for carbon pollution, provided the revenues are redistributed, i.e., made revenue-neutral. The poll’s finding is the most powerful indication yet that the public is warming to carbon taxation as the premier policy for combating climate change.

Stanford and RFF commissioned the polling firm SSRS to interview 1,023 U.S. adults on climate-related issues in January. Two findings from the poll — that Americans of Hispanic descent are particularly climate-concerned, and that half of Republicans would favor a presidential candidate who supports fighting climate change — led to front-page New York Times stories. (Click here for the story on Hispanics and here for the story on Republicans.) The full poll was made publicly available today at a briefing at the National Press Club in Washington.

Stanford and RFF commissioned the polling firm SSRS to interview 1,023 U.S. adults on climate-related issues in January. Two findings from the poll — that Americans of Hispanic descent are particularly climate-concerned, and that half of Republicans would favor a presidential candidate who supports fighting climate change — led to front-page New York Times stories. (Click here for the story on Hispanics and here for the story on Republicans.) The full poll was made publicly available today at a briefing at the National Press Club in Washington.

The poll was supervised by RFF university fellow Jon Krosnick, who has been polling Americans on climate change for two decades as head of Stanford’s Political Psychology Research Group. Its section on carbon taxation included these two questions: [Read more…]