Journalist-podcaster (at www.volts.wtf) David Roberts, What rural people really think about clean energy, Nov. 8. (Link is to transcript; this link goes to podcast.)

Gainsharing: Carbon Taxes Can Put Clean Energy Back in the Black

Note: This post distills and extends ideas from our Nov. 1 post, The Carbon-Tax Nimby Cure.

From the East Coast to Idaho’s high desert, big green-energy investments are foundering.

Composite of (top) first U.S. SMR complex (NuScale facility, artist’s depiction) and (below) offshore wind farm (Orsted’s UK Hornsea facility). Neither was in line for more than token revenues tied to displaced carbon emissions. Both have been cancelled.

Just in the past week, Danish wind giant Orsted scuttled the 2,248-megawatt Ocean Wind farm it was developing off New Jersey’s Atlantic coast, while NuScale scrapped its planned 462-MW complex of six 77-MW small modular reactors (SMRs) near Idaho Falls.

Both ventures were viewed as door-openers to new forms of large-scale U.S. carbon-free green power. They would have contributed mightily to decarbonizing their respective grids, taking the place of fossil fuel electricity now spewing nearly 4 million metric tons of carbon dioxide each year.

Their demise, along with dimming prospects for Equinor’s 2,076-MW Empire Wind farm off Long Island, NY, suggest that the vaunted crossover point at which big green-energy investments will come seamlessly to fruition fast and hard enough to rapidly decarbonize our grids is receding.

The 1983 title denoted “hard energy” facilities like giant power stations and LNG terminals. Nowadays it also seems apt for big green-energy projects.

The causes are no mystery: supply bottlenecks, spiraling materials costs, 40-year-high interest rates, Nimby obstruction. Not all of these will necessarily persist, but suddenly the combination looks daunting. Big energy projects, once derided as “brittle” by energy guru Amory Lovins, are rife with negative synergies. Nimbys stretch project schedules and impose punishing interest costs, particularly on big wind farms, a phenomenon we wrote about a week ago in The Carbon-Tax Nimby Cure.

Alas, Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act is not a panacea. IRA incentives primarily lift EV’s, rooftop solar, heat pumps, batteries and factories. By themselves they’re not going to refloat stalled clean power projects. The big push will have to come from somewhere else.

What a Robust Carbon Price Could Do for Green Energy

A robust carbon price could do the trick. Not a token price like RGGI’s $15, which is the per-metric-ton (“tonne”) of CO2 value of the 4Q 2023 permit price in the northeast US Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative electricity generation cap-and-trade program; but $50 or more per tonne of carbon dioxide, preferably $100.

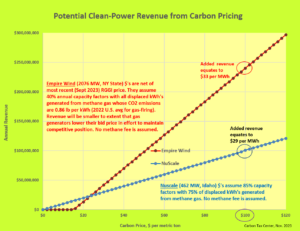

I’ve been calculating how much profit a robust carbon price could inject into clean-energy bottom lines. The numbers are so astounding that I checked and rechecked them. Here’s one: A $100/tonne carbon price in NY would allow Empire Wind to charge an additional $200 million or more each year for its output. How? Because the tax would raise the “bid price” for natural gas-generated electricity, the dominant power source and thus the price-setter on the downstate grid by so much — $30 to $35 per MWh, I estimate — that Empire Wind’s 7.25 million MWh’s a year could extract an additional $240 million in its power purchase agreement with the NY grid operator.

Lots to see here. The dollar figures, including the $/MWh bottom lines, are derived off-screen. Added revenues will be less if gas generators lower their grid prices somewhat, but will be more if the methane fee enacted as part of the 2022 IRA comes into play.

Same goes for NuScale. I estimate that its Idaho SMRs could command an additional $100 million a year (less than for Empire Wind because the project is smaller and not all of its output will replace fossil fuels). This additional value equates to $29 per MWh — nearly the same, coincidentally, as the $31/MWh climb in costs since 2021 that triggered NuScale’s cancellation, according to a report by the anti-nuclear Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

These added payments to clean-energy developers are not “subsidies.” They arise by slashing ongoing subsidies now enjoyed by fossil fuel providers and processors — in this case the methane-gas extractors and the electricity generators that burn the fuel — by subjecting these fuels to carbon pricing. The added payments will come about as the carbon price forces the gas generators to raise their sale price to the grid (to recoup their higher price to purchase the gas), which then creates room for Empire (or NuScale) to raise its prices.

Every cent of the carbon tax revenues will remain fully available for public purposes, whether to support low-income ratepayers, or invest in more clean energy or community remediation, or, our preference at CTC, as “dividend” checks to households. None of it needs to be earmarked to Empire or NuScale for them or other clean-power generators to rebuild their profit margins. The gainsharing comes about through pricing carbon emissions, not disbursing the carbon revenues.

Adios, Nimbys?

The Not In My Back Yard crowd wasn’t an apparent factor in NuScale’s downfall. (“Regulatory creep” was, but that’s a story for another time, not to mention one I dissected 40 years ago for the peer-reviewed journal Nuclear Safety.) But they certainly were for Ocean Wind in NJ and will be in NY if Empire Wind goes down the drain.

But here’s the thing: Not only would the added revenue allowed by the carbon price help return Empire Wind to the black. It would give Equinor, the developer, the wherewithal to spread so much largesse among the residents of Long Beach, LI (my hometown!) that they could subdue the Nimbys who have been able to hold up permitting by spreading scare stories about the routing of the project’s power cables underground. Nimby-ism solved, not by suasion (a fool’s errand) but by motivating the masses in the middle who evidently require more tangible inducements than saving the climate (or their beaches or homes).

Let’s Think Big

Ocean Wind, Empire Wind and NuScale are just a few examples of carbon-free projects that could again pencil out with robust carbon pricing. The question remains, how do we get there?

The point of this new analysis isn’t so much to tie clean energy to carbon pricing, but to enlist the political power and prestige of clean-energy entrepreneurs and developers on the side of carbon-tax advocacy.

As we noted in our previous (Nov. 1) post, during headier carbon-pricing times (2007 to 2011) the Carbon Tax Center attempted, alongside allies like Friends of the Earth, the Friends Committee on National Legislation, and Citizens Climate Lobby, to induce the American Wind Energy Association, the Solar Energy Industry Association and other green-tech trade groups to join us in advocating carbon taxing. We put out similar feelers to the Nuclear Energy Institute and the American Nuclear Energy Council. Getting the U.S. nuke lobby behind carbon taxing should have been a no-brainer, given that carbon taxes that monetized the climate value of nuclear power plants’ combustion-free electricity could have supplied mega-dollars to keep extant reactors solvent.

2010 redux: Equation at left signifying “Renewable Energy cheaper than Fossil Fuels” was a cleantech meme. Button on right, created by then-CTC senior policy analyst James Handley, was less prevalent. Time to meld the two?

No dice. We weren’t granted even one conversation with the nuclear folks. The wind and solar people, for their part, insisted that unending cost reductions through increased scale and efficiency, along with green power’s inherent magical appeal, would propel them past any obstacle. Why besmirch our Randian aura with energy taxes, they seemed to say, when our tech is going to usher in energy abundance and spare earth’s climate?

Things look different now. Big, carbon-free power ventures — the ones that everyone from governors and ambassadors to scientists and schoolkids are counting on to get us off fossil fuels — are beset by troubles: financial, logistical, cultural.

Without genuine carbon pricing that accords clean energy the economic rewards to which it’s entitled, too many large-scale green energy projects are going to come up short. As we asked in that earlier post: Will clean-power developers look at this week’s NJ and Idaho losses, among others, and decide that they need a carbon tax every bit as much as the climate does?

The Carbon-Tax NIMBY Cure

NY Gov. Kathy Hochul last month vetoed a bill that could have expedited a huge wind farm in the Atlantic Ocean off Long Island. Her veto imperils not just the project, called Empire Wind, but New York State’s hopes to decarbonize its electric grid and validate its claim to national climate leadership.

I’ll argue here that a state or federal carbon price — one more substantial than the relative pittance of $15 per ton now being charged for electricity sector emissions under the RGGI compact — could have helped the developers beat back the NIMBYs whose rabble-rousing helped force Hochul’s hand. Let’s review the project and then explain how its difficulties are connected to the absence of robust carbon pricing.

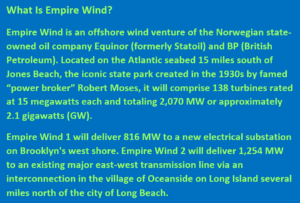

Empire Wind Will Be Large

There will be 138 turbines, identical and gigantic. At 387 feet, each turbine blade will be the length of a football field including the end zones. The distance from water surface to blade tip at full height will be 886 feet, roughly the extent of two celebrated Manhattan towers that a century ago were the world’s tallest buildings: the 792-foot Woolworth Building (#1 from 1913 to 1930) and the 1,046-foot Chrysler Building (1930-1931). An even funner fact, from the developer’s spec sheet, is this: just one complete rotation by one turbine’s three blades will “power a New York home for about 1.5 days.”

There will be 138 turbines, identical and gigantic. At 387 feet, each turbine blade will be the length of a football field including the end zones. The distance from water surface to blade tip at full height will be 886 feet, roughly the extent of two celebrated Manhattan towers that a century ago were the world’s tallest buildings: the 792-foot Woolworth Building (#1 from 1913 to 1930) and the 1,046-foot Chrysler Building (1930-1931). An even funner fact, from the developer’s spec sheet, is this: just one complete rotation by one turbine’s three blades will “power a New York home for about 1.5 days.”

The anticipated annual electrical generation from Empire Wind 1 and 2 combined is 7.25 TWh (or, if it’s easier, 7,250,000,000 kilowatt-hours),assuming a 40% yearly capacity factor. Here are four alternative ways of visualizing the significance of that output:

- Empire Wind’s 7.25 TWh is half again as great (i.e., 1.5x as large) as the entire production by New York State wind turbines in 2022 (that figure was 4.8 TWh);

- 7.25 TWh is 5 to 6 percent as great as all electricity generated from all state sources in 2022 (130.5 TWh);

- 7.25 TWh is one-sixtieth (1/60) as much as all U.S. wind-generated electricity last year (435 TWh), a figure that itself constituted a tenth of U.S. electricity production from all sources;

- 7.25 TWh is close to (12 percent less than) the average annual 2010-2019 output of either of the twin Indian Point reactors in suburban Westchester County that until their recent forced retirement were downstate New York’s lone large-scale source of carbon-free electricity. (The entire Indian Point station’s average annual output over its final decade, 2010-2019, was 16.5 TWh.)

Putting aside that last benchmark — which is intended as a reminder of the carbon disaster of shutting Indian Point (and a cautionary tale against shutting its West Coast doppelganger, Diablo Canyon) — Empire Wind looms large in New York state’s goal of attaining a 70 percent carbon-free grid in 2030.

The state’s 2022 carbon-free electricity share was just 48 to 49 percent, down from 60 percent in 2019, before Indian Point’s closure commenced. If Empire Wind’s output were available today, the statewide share would stand at 54 percent, indicating that this single (albeit two-part) project can close a quarter of the gap from the current clean percentage to the 2030 target.

Hochul and the NIMBYs

Along with infusing the grid with billions of clean kilowatt-hours, building and servicing Empire Wind 1 and 2 is expected to create 1,300 permanent onshore jobs — 300 to manufacture turbine components at the Port of Albany, and 1,000 in operation and maintenance at the South Brooklyn Marine Terminal, according to Equinor, the developer. These numbers, along with the clean electricity, ought to be catnip for any Democratic politician.

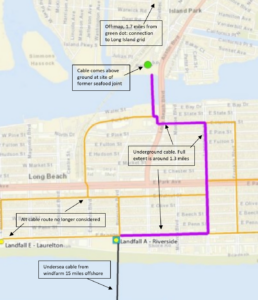

Why, then, did Hochul on Oct. 20 veto a bill that could have cleared the path for the Empire Wind 2 power cable to run under Long Beach and connect to the electric grid in Oceanside?

There’s no shortage of possible rationales. Long Island flipped from shaky blue to all red a year ago, as Democrats lost all four Congressional races and a number of state legislative seats while Hochul herself was outvoted there in her unnervingly close re-election. She may be seeking to preserve political capital for a possible renewed push to undo exclusionary zoning that that keeps housing in Nassau and Suffolk counties unaffordable for newcomers or those without generational wealth. Moreover, Empire Wind itself has faced financial headwinds due to supposed supply chain bottlenecks and spiraling financing costs, with the latter due in no small part to the regulatory delays.

Whatever the reasons, Hochul went all NIMBY-friendly. Her veto message faulted Equinor for running roughshod over Long Beach residents (see pull quote at left) rather than calling out the obstructionists for teeing up a replay of 2012’s Superstorm Sandy that devastated the very communities that now are clamoring for the wind project to go away.

In her message, the governor ignored the tinfoil-hat essence of most anti-wind opposition, which one observer, a former New York City chief climate policy advisor, characterized as combining “propaganda from the fossil fuel industry, rumor mongering in local communities, and basic nimbyism.” As NY Focus helpfully reported in Long Island Politicians Claim Victory for Hochul Wind Power Veto, objections to the Empire Wind farm and cables run the gamut from shopworn (ocean views sullied by turbines 15 miles offshore) to debunked (health-harming electromagnetic radiation from the power cables) to chronologically impaired (“We’ve had a huge number of [dead] whales that are showing up on our beaches,” a state senator fretted, yet not even a single offshore wind turbine has begun operating on the Atlantic Coast).

Entire cable route through Long Beach is underground. Yet NIMBYs are holding hostage a not-quite-in-their-backyard project that would more than double NY wind power production. Incidentally, I was born and grew up in a house on Washington Blvd, just a few blocks past the left edge of the map. Equinor map adapted by CTC.

Hochul and her staff seem unaware that there is no placating NIMBYs, whether their sights are trained on giant offshore wind projects or small-bore items like transit-friendly higher-rise housing or bike lanes. To the naysayers, any palpable change in their way of life is either Armageddon in itself or a pathway to purgatory. The only way to deal with them is to give pro-development, pro-change forces the strength to vanquish the NIMBYs outright — which is where carbon pricing comes in.

Would You Like $240 Million in (Annual) Carbon Benefits With Your Order?

Offshore wind’s chief virtue — in some respects, its true raison d’être — is its ability to take the place of dirty, fossil-fuel electricity generation in the grid. This asset is particularly salient in the case of Empire Wind, insofar as the downstate New York grid, with only modest interconnections to greener grids upstate or elsewhere, obtains more than 90 percent of its annual electricity by burning methane (“natural”) gas.

As a result, nearly every kilowatt-hour from Empire Wind will directly displace a kWh from burning fracked gas. And though the 90% share will decline when the new Champlain-Hudson Power Express transmission line enters service, perhaps in 2026, nearly all of the “incremental,” hour-by-hour power production actually avoided by generation from Empire Wind will still be gas-fired when the project’s two parts come on line in 2028 and 2029.

Now picture a federal or state carbon tax — or “price” if you prefer. Set it at $100 per metric ton (“tonne”) of CO2, which is both a round number and the level the Carbon Tax Center has been advocating since our inception, to be reached after a ramp-up taking half-a-dozen years. Now apply the carbon tax to the CO2 emitted from one kWh generated by burning gas. You’ll find that the carbon tax associated with each such kilowatt-hour is 3.9 cents.

Calculations: 659 x 10^6 tonnes (CO2 emissions from 2022 U.S. gas-fired electricity) divided by 1.689 x 10^12 kWh (U.S. electricity generated with gas in 2022) multiplied by 10^4 ¢ charged per tonne yields 3.90¢/kWh.

Let’s bring that figure down to earth: With a $100/ton (okay, tonne) carbon tax, each gas-fired kWh in competition with Empire’s offshore wind would cost 3.9 cents more to generate than at present. (To keep the discussion simple, I’ve refrained from counting an additional tax on methane.) We trim that to 3.3¢/kWh because the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) already charges a carbon price on fuels used to generate electricity in New York and neighboring states; in the most recent (September) quarterly auction, that price reached $13.85 per short ton, equivalent to $15.25 per metric ton, which we deduct from our aspirational $100/tonne carbon price to avoid double-counting, reducing it by just over 15 percent.

The hypothetical 3.3¢/kWh additional carbon charge for gas-generated electricity (stemming from the $100 carbon price) multiplied by Empire Wind’s 7.25 TWh annual output yields $240 million per year. Those dollars represent a first estimate of the additional annual revenue Equinor could have sought in its 2018 and 2020 bids responding to NYSERDA’s solicitations to prospective developers of offshore wind projects. (See text box further below.) With a robust NY carbon price, in other words, Equinor’s Empire Wind venture would enjoy a far higher profit margin.

Offshore Wind’s Missing Carbon Price

Imagine what Equinor might have done with $240 million a year in additional Empire Wind revenue. It could have banked, say, half that amount to offset the price escalation and higher interest costs that this year lowered its prospective profit margins and compelled it to appeal to NY State to grant a higher price for its production. (Incidentally, the NY Public Service Commission’s Oct. 12 order denying Equinor’s petition seeking renegotiation of its power contract with NYSERDA provides a good capsule summary of NY state offshore wind activity; it can be found via this link; search for Cases 15-E-0302 and 18-E-0071.)

The other $120 million, or a good chunk of it, could have been used — and might still be — to provide economic benefits to Long Beach and other communities that consider themselves “affected” by Empire Wind’s turbines or cables.

Empire Wind website paragraph about Taxes makes no mention of payments — voluntary or mandatory — to Long Beach and other communities.

As a thought-experiment, consider that $120 million distributed equally to Long Beach’s 11,700 households (assuming the city’s 35k population resides 3 per household) could provide recurring yearly dividends of around $10,000 per household, once the electricity began to flow. Perhaps more practical would be to set aside $75 million as a one-time payment to retire the so-called Haberman Judgment holding Long Beach financially responsible for blocking a proposed real-estate venture near the boardwalk and ocean beach several decades ago (see City of Long Beach 2023-2024 adopted budget, pages ii-iii).

Of course there are any number of other “improvements” that Long Beach, Island Park and Oceanside might elect to be funded by Equinor “payments in lieu of taxes.” I was surprised that Empire Wind’s online materials do not mention any such payments.

The idea is not to “win over” the NIMBYs — I consider that a fool’s errand — but to neutralize and politically overpower them by appealing to the larger community’s enlightened self-interest. Not so much the members of the Long Beach city council — who apparently (and astoundingly) went from 5-0 in favor of permitting the cable route to 0-5 between spring and fall of 2023 — but the citizenry that holds sway over them.

This isn’t my first time linking carbon pricing to big, hence potentially intrusive, green-energy projects. I struck that note in 2006, in Whither Wind, a long-form piece on wind and other green power for Orion magazine:

[I]if carbon fuels were taxed for their damage to the climate, wind power’s profit margins would widen, and surrounding communities could extract bigger tax revenues from wind farms. Then some of that bread upon the waters would indeed come back — in the form of a new high school, or land acquired for a nature preserve.

The urgency now is far greater. Today, as I was wrapping this post, the New York Times reported that the Danish offshore wind company Orsted canceled an equally large (2248 megawatts) wind farm, Ocean Wind 1 and 2, it was developing off New Jersey’s Atlantic coast. Orsted cited the same combination of faltering economics and local opposition (which of course weakens the economics further through delays) now besetting Equinor and Empire Wind. Note too that even though Empire Wind 1’s interconnection to the grid, also under the seabed but through Brooklyn, is not (now) threatened, the economics will almost certainly kill Part 1 if Empire Wind 2 through Long Beach goes down.

The urgency now is far greater. Today, as I was wrapping this post, the New York Times reported that the Danish offshore wind company Orsted canceled an equally large (2248 megawatts) wind farm, Ocean Wind 1 and 2, it was developing off New Jersey’s Atlantic coast. Orsted cited the same combination of faltering economics and local opposition (which of course weakens the economics further through delays) now besetting Equinor and Empire Wind. Note too that even though Empire Wind 1’s interconnection to the grid, also under the seabed but through Brooklyn, is not (now) threatened, the economics will almost certainly kill Part 1 if Empire Wind 2 through Long Beach goes down.

Long-time CTC followers will recall my standing frustration over wind and solar entrepreneurs’ lack of interest in pushing carbon pricing. Efficiency gains, cost reductions and the magical appeal of green power would carry them over any and every threshold, they imagined. Will today’s NJ offshore wind defeat and the one looming in NY be enough to convince clean-power developers that they need a carbon tax every bit as much as the climate does?

Nordhaus assures us in his DICE model that growth continues like a cruising Cadillac on the California coast with an occasional pothole. But the reality is rainstorms, mudslides, earthquakes, and other drivers on the road.

Christopher Ketcham, in When Idiot Savants Do Climate Economics How an elite clique of math-addled economists hijacked climate policy, The Intercept, Oct. 28.

Exxon’s $59 Billion Spike Through Divestment’s Heart

The impossibility of throttling Big Oil through fossil fuel divestment campaigns was laid bare last week when ExxonMobil announced it was acquiring Pioneer Natural Resources, the #1 driller in the #1 producing U.S. oilfield, the Permian Basin.

Chart from macrotrends.net shows ExxonMobil’s market capitalization (stock price x shares outstanding) last week near an all-time high.

In a transaction priced at $59.5 billion, Pioneer shareholders will receive slightly more than 2.3 shares of ExxonMobil stock for each Pioneer share. No banks are involved, no debt, no third parties; and, most noteworthy, no cash. Pioneer’s management evidently holds Exxon’s current and future financial strength in such high regard that it was willing to sign on to an all-stock deal.

Had it been necessary, though, Exxon could have bankrolled the entire acquisition using cash generated by its sales of petroleum products to U.S. and world motorists, truckers, air travelers and shippers. Last year alone, Exxon generated more than enough cash flow, $76.8 billion, to buy Pioneer outright. Its market capitalization stands at $450 billion, triple the lows during the 2020 pandemic year and higher than the $400 billion in 2012, when climate author-activist Bill McKibben kicked off the divestment movement with his Rolling Stone manifesto, Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math.

Photos by Johnny Silvercloud (L, 2015) and Herb Keeney (R, 2016). Thousands of similar images and hundreds of divestments haven’t crimped the coffers of Exxon and its oil brethren.

McKibben was admirably candid about wanting to “make clear who the real [climate] enemy is”: the fossil-fuel industry, led and epitomized by the oil-and-gas giant ExxonMobil. The eleven intervening years have cemented Exxon’s standing as Big Oil incarnate. Not only is Exxon the industry’s most technologically proficient and politically connected member, it’s the one that for decades sowed disinformation about climate change even as its own scientists advised management to fortify the company’s drilling platforms against rising seas.

Unsurprisingly, “Exxon Knew” ranks high among contemporary climate-protest slogans. And the company certainly merits every ounce of opprobrium directed at it. Divestment was a righteous idea, but it has proven futile.

Wake-Up Call

The Pioneer acquisition should be a wake-up call. If the wave of divestments over the past decade by universities, philanthropies and pension funds had genuinely dented oil industry prospects, Exxon’s stock wouldn’t have had the cachet to lure Pioneer into an all-stock purchase. Nor would Exxon have been able to pull off a Plan B of forking over $60 billion in cash. The ease of the acquisition puts the lie to divestment’s starve-and-shame paradigm intended to dry up dollars and discredit industry brands.

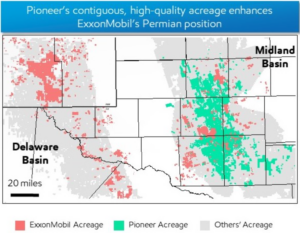

Permian Basin map from ExxonMobil Oct 11 news release.

Pressuring institutions to divest from fossil fuels never made much sense as a pro-climate strategy. Targeting any one oil company was never going to be able to restrain carbon emissions. No single company supplies more than a small slice of the world’s petroleum.

Indeed, as Bloomberg News reported last week, even with Pioneer, Exxon will account for only 15 percent of Permian Basin extraction and a far smaller share of world oil production — three or four percent, according to my calculations. At that modest scale, a hole in any one company’s finances would simply make room for others.

Divestment’s futility actually went deeper, though. In the oil business, access to capital markets matters hardly at all. Most of the time the industry is flush with cash. Just about everything it does — exploration, extraction, pipelining, refining, selling — is self-financing, paid for by the ceaseless ka-ching from sales of gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, bunker fuel and other petroleum products, not to mention natural (methane) gas, which in 2022 provided nearly three-fourths as much primary energy worldwide as petrol, according to BP’s 2023 Statistical Review of World Energy (covering 2022).

To be fair, divestment campaigning did appear to penetrate Exxon’s inner sanctum in 2021, when the activist hedge fund Engine No. 1 succeeded in electing three directors to ExxonMobil’s 13-person board. “Exxon’s Board Defeat Signals the Rise of Social-Good Activists,” trumpeted the New York Times headline reporting the surprise incursion. Yet the ideological impact, if there was one, was short-lived. All three insurgent members backed the Pioneer acquisition, the Wall Street Journal reported last week.

WSJ Oct 14 headline canonizing Exxon CEO Woods for his $60B Permian Basin play.

Indeed, in the Journal story, Charles Penner, architect of the Engine No. 1 campaign, says the Pioneer deal “shows Exxon had heard some of the campaign’s critiques and changed its approach to focus on returns instead of costly megaprojects more dependent on long-term demand.” Oof. The story has nothing from Engine No. 1 on Exxon’s present or future complicity in climate-damaging emissions generated from its products. And nothing in its detailed portrait of CEO Darren Woods suggests that worries about divestment ever cost him a moment’s sleep.

What To Do?

There are so many climate campaigns needing and deserving of the energies now squandered pursuing fossil-fuel divestment. I suggested a few of them in The Climate Movement In Its Own Way, my April 2022 article in The Nation (reposted here at CTC). Here’s a top-10 list (in no particular order):

- Policy campaigns to curb motor vehicle size and weight

- Organizing to expedite up-zoning in cities and suburbs and otherwise promote housing density

- Advancing walkable, bikeable and transit-oriented communities

- Restricting and overcoming NIMBY power to block wind farms and solar arrays

- Supporting the operability of existing, well-functioning nuclear power plants

- Advancing congestion pricing and other road-pricing / traffic-pricing proposals (valuable for themselves and as templates for broad carbon-emission pricing)

- Taxing extreme wealth, to both attack luxury emissions and promote social solidarity needed to tackle carbon consumption

- Shrinking the local, state and national reach of the world’s sole major climate-denying political party (whose dysfunction is currently in especially plain sight, as NY Times columnist Jamelle Bouie trenchantly documented this week)

- Reducing animal agriculture through both culture and policy change

- Advancing or at least keeping alive the idea of robust carbon pricing at the state and especially national level

Note that all of the above measures, except perhaps #8, attack carbon and other greenhouse gas emissions from the demand side, insulating them from the all-too-real whack-a-mole syndrome that undermines most supply-side climate campaigns due to global substitutability by which increased drilling “there” offsets halts to drilling “here.”

Missing from the list: abetting the electrification of cars, trucks, cooking, heating and industry. Why not? For one thing, “electrify everything” has no shortage of NGO advocates like Rewiring America, and, thanks to President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, it enjoys generous federal subsidies. For another, decarbonization of U.S. grids is far from complete and, in many states and regions, painfully slow.

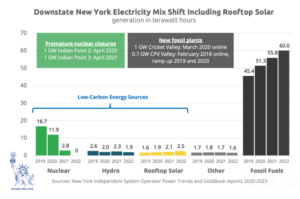

Graphic and data curated by Isuru Seneviratne, Nuclear NY, Oct 2023.

Here in New York City, CTC’s home territory, fossil fuel burning today generates more than 90 percent of all electricity (see graphic from Nuclear NY), down from 70 percent since the 2020-2021 closure of the downstate grid’s only large-scale non-carbon generator, the Indian Point nuclear plant.

As a result, rarely if ever is the incremental electricity that my grid calls on to recharge EV’s or energize electric heat pumps generated from a non-carbon source. The same is true at present in much of the United States. Electrification, an essential long-term program, is not yet a carbon-eliminating panacea .

Want to hurt Exxon AND fight climate change? Work to bring robust carbon pricing back into the national policy conversation. A meaningful carbon price — one that quickly ramps up to triple digits per ton of CO2 — will crimp the oil business, the coal business and the fossil-gas business, harming the fossil fuel industry’s shareholder value and political power, while effectuating steady and significant reductions in combustion. And, when considering the to-do list above, keep in mind that robust carbon pricing (#10) enhances all of the others.

Addendum: Two days after posting, we learned that Chevron is acquiring oil giant Hess Corp. in another all-stock deal, this one valued at $53 billion.

Climate action is dwarfed by the scale of the challenge. We must make up time lost to foot-dragging, arm-twisting and the naked greed of entrenched interests raking in billions from fossil fuels.”

United Nations secretary general Antonio Guterres, while convening the U.N. Climate Ambition Summit, reported in At a Summit on Climate Ambition, the U.S. and China End Up on the B List, New York Times, Sept 20.

NYC Climate March: Unsettling but Inspiring

Sunday’s March to End Fossil Fuels in midtown Manhattan was big, loud and vibrant. The organizers put the tally at 75,000. While that may have been over-generous, the march was far and away the largest U.S. climate assemblage in some time.

It was also an occasion to ponder the goals and tactics of the climate movement.

The customary signs and chants denouncing Big Oil and its funder banks were out in force. What felt new, and unsettling, was the vitriol directed at President Biden. Last year’s passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, with its promise to hasten the transition from fossil fuels by accelerating wind and solar and electrification, might as well have been an hallucination.

This photo by Sarah Blesener ran above the fold in the New York Times’ print edition the next day. The paper’s online caption caught the focus of the march: “Protest organizers used Sunday’s event to send a message to President Biden as he begins his push for re-election: Do more if you want our votes.”

Ganging Up On Joe

The signs and chants castigating the president flowed like a river. Biden: Declare a climate emergency … Cancel Willow … I didn’t vote for fires and floods.

Yikes. Whatever happened to the Inflation Reduction Act’s nearly half-a-trillion dollars worth of tax credits and other subsidies paying down the cost of renewable electricity from solar and wind farms while also cutting consumer costs to purchase electric vehicles, electric heat pumps, and home and commercial electric battery storage?

The intent of the IRA’s myriad and synergistic incentives isn’t just to grow the U.S. green manufacturing base with good-paying green jobs. It’s to displace fossil-fuel use by retiring petrol-fueled engines and furnaces and simultaneously “greening the grid” by speeding the rate at which wind and solar power usurp electricity generation from coal and methane gas.

As the IRA was snaking through Congress last August, energy analysts were scoping the potential carbon and methane reductions from those displacements, along with estimates of increased emissions from new federal oil and gas leasing that Biden committed to expedite to win the tie-breaking Yes vote from West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin. One leading think tank, Energy Innovation, concluded that “The bill’s clean energy measures will yield 24 times more emissions reductions than its fossil fuel provisions will increase emissions.” (The firm subsequently raised its 24-to-1 emissions ratio to 28-to-1.)

Seven months later, Biden held up his end of the deal, issuing a permit okaying ConocoPhillips’ $6 billion Willow oil-and-gas drilling venture on Alaska’s North Slope — and threw away the climate good will due him from the IRA. Never mind that the additional carbon emissions from the Biden-Willow “hydrocarbon bomb” will only negate a fraction of the emission reductions from his legislation’s clean electricity and end-use electrification, as I pointed out back in March. Even more poignantly, those additional emissions are more properly estimated to be close to zero. Why? Because what actually burns the carbon fuels and puts the CO2 into the atmosphere is fossil fuel consumption, not supply. If Biden had rejected Willow, the same supply would have been called forth from Nigeria, or Kuwait or some other oil region or state to fill U.S. cars, planes and trucks.

In other words, Willow or any new U.S. drilling activity is nearly irrelevant from a climate standpoint because, as we wrote then, “demand finds a way to create supply,” rather than the reverse.

As we marched, I asked a smattering of anti-Biden sign-holders if the president merited praise for the green energy unleashed by his IRA, rather than criticism for okaying Willow or the other contentious project, the Mountain Valley Pipeline through West Virginia. The typical response was No, we’re in a climate emergency. Any new fossil-fuel infrastructure is too much.

To be sure, trade-offs are hard to wrestle with even in calm moments, much less among a big crowd on the move. But the blank stares about the IRA and occasional flashes of venom against Biden were disquieting, nonetheless. The Times‘ headline for its print report on the march was all too accurate: “Fingers Pointed at President, Protesters Demand End to Fossil Fuels.” Left unsaid is whether protesting Biden climate bombs will seed electoral bombs in 2024, placing our democracy as well as climate in irredeemable peril.

Who’s Really Funding Fossil Fuels?

If the anti-Biden sentiment was novel, the anti-big banks rhetoric was old hat. Blaming the climate crisis on Big Oil and demanding that universities, pension funds and the like “divest” by dumping fossil fuel securities from their holdings, has been a staple of climate organizing for nearly a dozen years, as I decried a year-and-a-half ago, in Exxon doesn’t care if you divest. Neither does climate:

When the writer and climate activist Bill McKibben kicked off the [divestment] campaign in a July 2012 Rolling Stone article, Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math, the rationale was three-fold: (1) dry up capital and make it harder for the fossil fuel industry to create new mines, wells, pipelines and terminals; (2) weaken the industry’s social and political standing so it couldn’t easily block pro-climate policy; and (3) by hanging a “Dump Me” sign around Big Oil, amp up climate organizing. Not for nothing did McKibben subtitle his Rolling Stone article, “Make clear who the real enemy is.” It was Exxon and its brethren.

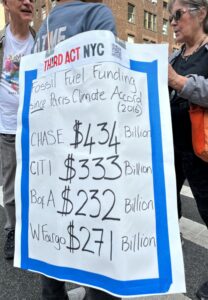

A climate marcher with Third Act helpfully displayed the biggest U.S. banks’ fossil-fuel financing over the past seven years.

That path has proven to be a dead-end, I concluded in my post. One piece of evidence was a simple graph showing that Exxon-Mobil’s share price had outperformed the stock market as a whole since the onset of the Covid pandemic. More evidence, if any were needed, was available in the wonderfully wonky signboard at left that was borne by one of yesterday’s marchers, a vibrant senior citizen affiliated with the McKibben-inspired Third Act.

The amounts that the four banks — Chase, Citi, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo — have funneled into fossil fuels since the start of 2016 sum to an impressive-seeming $1.27 trillion ($1,270,000,000,000). Yet over the same period, consumption of petroleum products by U.S. families and businesses earned the oil companies a revenue haul nearly three-and-a-half times as great: an estimated $4.29 trillion ($4,290,000,000,000).

[I calculated that figure from the average 19.9 million barrels per day of gasoline, diesel fuel, jet fuel and other petroleum products kerosene and so forth consumed per day over the same seven years, 2016-2022. (See Energy Information Administration, Monthly Energy Review, Table 3.5 Petroleum Products Supplied by Type.) Factoring in (1) there are 42 gallons of petrol per barrel, (2) the seven years total 2,555 days (365 x 7), and 3) an average retail price per gallon sold of $2.00 — a conservative markdown from the actual $2.82 average retail price of gasoline over that period — yields $4.29 trillion.]

Who’s really funding fossil fuels? American households, businesses and institutions, locked into grotesque consumption levels that U.S. climate activists studiously ignore.

To be sure, my dollar comparison has apples-and-oranges elements. Only some of the $4 trillion or more in petrol sales is available for investment in exploration and other petroleum infrastructure. And other banks beyond the Big Four also fund oil investment. On the other hand, U.S. consumption of methane gas and coal fossil fuels now exceeds consumption of petroleum on a Btu basis by 20 percent, suggesting that total fossil fuel revenues over the past six years was probably in the vicinity of $8 billion rather than the $4.3 billion from petroleum products alone.

My point is that bank financing is a much weaker linchpin for creating new fossil fuel infrastructure than most climate activists suppose. What really makes fossil supply possible is the lock-in of consumption of fossil fuels themselves, in billions of routine purchases that, day in and day out, fork over many more dollars to the fossil fuel industry than do the banks.

(Owens was responding to a Cameron Murray, PhD, who was decrying the idea of asking Americans to take some responsibility for their personal carbon footprint.)

Or, as Darrell Owens, an analyst with CA YIMBY (Yes In My Back Yard), the pro-housing group that has spearheaded the recent revolution of expansionary zoning in California, put it recently on Twitter, “Oil drilling [and such] isn’t for fun, it’s in service of carbon intensive demand that can be stopped.” Stopped how? By undoing automobile dependence, incentivizing smaller vehicles, densifying suburbia, introducing congestion and road pricing, and of course, federal-level carbon taxing, as I detailed last year for The Nation magazine (The Climate Movement In Its Own Way).

Uprooting the Source: Carbon Consumption

Happily, some at Sunday’s march saw past Biden and the banks and critiqued the structures of consumption that enforce dependence on fossil fuels, whether directly at the gas pump or the furnace or stove, or indirectly in purchases of products whose manufacture and transportation entail massive quantities of fuel, or in inefficient or indulgent use of electricity, most of which is still made by burning coal or methane gas.

These included stalwarts from Citizens Climate Lobby, including an enthusiastic contingent from Pittsburgh as well as folks from across the Northeast; and individuals whose handcrafted signs called out U.S. car culture not only for its gasoline profligacy but for its stifling of human life and health.

Some marchers saw beyond Biden and bankers to demand enduring solutions: carbon fee-and-dividend and liberation from automobiles.

“Tax Pollution, Pay People” packs so much into four words, I said to the sign-holder, a CCL member from Pittsburgh, who told me his name, which I failed to write down. When I told him mine, he nearly jumped out of his shoes and shouted it to his fellow CCL’ers as if I was Greta Thunberg and Steelers legend Franco Harris rolled into one.

I started to apologize for CTC’s relative quiescence over the past year or two and to explain that I’ve been consumed with helping get NYC’s congestion pricing plan across the goal line. He stopped me short, thanking me for CTC’s work and insisting that, together, we’ll win a nationwide price on carbon before it’s too late.

So there’s my take. Singling out Biden for attack felt excessive and worrisome, since any falloff in enthusiasm will crimp the chances of small-d democratic, climate-aware outcomes in the elections next year. Similarly, more than a decade’s worth of targeting Big Oil and the banks doesn’t appear to have moved the needle for effective climate policy. Going after “luxury carbon,” as Extinction Rebellion did in a small but resonant climate action last week that I helped organize, feels to me like a more empowering path, one that might capture both the populist moment and climate urgency in a single stroke.

But notwithstanding the mis-directions, it was uplifting to be amidst tens of thousands with a like mind: A better world is possible. A better world is necessary. I want a fossil-free president. Amen to that!

Watching TV and seeing everything burn, it’s hard to stay interested in world problems when there won’t be a world. Every summer will be hotter. It will always be worse.”

Italian student Sara Maggiolo, 16, quoted in How Do We Feel About Global Warming? It’s Called Eco-Anxiety, by Jason Horowitz, New York Times Rome bureau chief, Sept. 16.

In many parts of the world, including some of the most densely forested, trees are not perfect allies for tree-huggers anymore, and forests no longer reliable climate partners. What was once the embodiment of environmental values now seems increasingly to be fighting for the other side. In some places, fighting harder each year.”

NY Times climate correspondent David Wallace-Wells, in Forests Are No Longer Our Climate Friends, Sept. 6.

Asked what the country should do to combat climate change, Diana Furchtgott-Roth, director of the Heritage Foundation’s energy and climate center, said ‘I really hadn’t thought about it in those terms.’”

A Republican 2024 Climate Strategy: More Drilling, Less Clean Energy, by Lisa Friedman, published in the NY Times, Aug. 4.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- …

- 170

- Next Page »