Impacts of Australia’s Carbon Price, 9 Months In (Mondaq Blog)

CTC’s Carbon Tax Model: Peering Under the Hood … and Beyond

This post is a response to a set of five questions we received from Paula Swedeen, an ecological economist from Olympia, WA. Paula graciously granted permission to reprint her e-mail; our answers follow each of her five questions.

Hello Mr. Komanoff — I recently downloaded and read through your updated carbon tax model. Thanks for making this publicly available — it’s an extremely useful tool for thinking through how a carbon tax might work and potential optimal designs. I also read the exchange that you and your colleague James Handley had with Dave Roberts at Grist last November-December which laid out some interesting questions about how to spend revenue from a carbon tax. I have a few questions about the policy implications of the results of your default case, and about some of the assumptions in the model.

My background is in ecological economics and biology, and I work quite a bit at the intersection of forests and climate change. I consult for non-profit environmental groups and Tribes on conservation policy for forests and aquatic ecosystems. While I have worked on the portion of California’s climate policy that impacts forests, I am not wedded to using cap-and-trade for addressing climate change, and think a carbon tax has some important advantages at the national level.

Here are my questions.

1) Your default case of starting a tax at $15/ton of CO2 and increasing it by $12.50 a year results in an average rate of emission reductions of 2% per year between 2014 and 2036 (amount of average annual reductions compared to emission levels in 2013, the year before the tax starts). While this results in substantial reductions compared to what we are doing today, much research, as you are no doubt aware, points to the need for global emissions to decline at rates in excess of 5-6% per year, starting now, in order to meet even a 50% chance of staying below a 2 degree C temperature rise (a frighteningly weak goal to start with). From a global equity perspective, the U.S. ought to at least meet that average requirement, if not exceed it given our historical emissions. See for example, Anderson and Bows, 2011 (http://rsta.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/369/1934/20.full.pdf+html).

1) Your default case of starting a tax at $15/ton of CO2 and increasing it by $12.50 a year results in an average rate of emission reductions of 2% per year between 2014 and 2036 (amount of average annual reductions compared to emission levels in 2013, the year before the tax starts). While this results in substantial reductions compared to what we are doing today, much research, as you are no doubt aware, points to the need for global emissions to decline at rates in excess of 5-6% per year, starting now, in order to meet even a 50% chance of staying below a 2 degree C temperature rise (a frighteningly weak goal to start with). From a global equity perspective, the U.S. ought to at least meet that average requirement, if not exceed it given our historical emissions. See for example, Anderson and Bows, 2011 (http://rsta.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/369/1934/20.full.pdf+html).

What other policies, in addition to the already robust carbon tax you propose, do you see as being available to accomplish the other 3-4% annual rate of emission declines we should be achieving?

Answer: Our default tax is based on the 2009 Larson bill. I calculate a slightly stronger reduction rate for it than you did: 2.5% a year from 2012 to 2036. (Here I’m comparing projected 2036 emissions of 2,860 million metric tons of CO2 with actual 2012 emissions of 5,243, and of course I’m compounding the average.) But your point stands.

To some extent, that disturbingly small average is an artifact of the diminished “bite” built into any additive tax that increments by a constant annual amount: the tenth $12.50/ton tax increment has less salience to households and industry than the first. At some point, the additive rises would need to give way to constant-percentage-increase rises, unless the rate had already achieved market-clearing levels — a scenario we critiqued in this space several years ago as over-optimistic.

Any model tends to have greater predictive value in the near term than the far, and thus we’re more heartened by the 3.1% average decline rate predicted for the first dozen years than we are discouraged by the 1.9% average rate for the second dozen. But even a 3% annual decline rate is wanting, as you noted.

The ideal carbon tax is, thus, steeper even than Larson’s “aggressive” bill. But we have to begin somewhere. As for complementary policies, we’re impressed with the 100% Wind-Water-Sunlight vision propounded by Stanford professor Mark Z. Jacobson and his team. His new paper in Energy Policy, “Examining the feasibility of converting New York State’s all-purpose energy infrastructure to one using wind, water, and sunlight,” is a good place to start.

2) In your exchange with Dave Roberts, you acknowledge that there are barriers to clean technology deployment, but state that the strength of your tax compared to the proposals coming out of Brookings or MIT would exert more technology pull to overcome these barriers. However, given that this pull looks to result in about half or less of the rate of emission reductions needed, does this influence your perspective on whether spending some of the revenue from a carbon tax on deployment and R&D would be worthwhile?

Answer: We’re all for basic energy research, but less enamored of government-funded development and deployment. In any event, we believe that dedicating “incremental carbon-tax revenue” to transparent and progressive federal tax-shifting or per-household dividends will do more to cut carbon than spending it on RD&D. It will do so by preserving the political bargain that makes possible next year’s carbon-tax increment, and the increment after that, and so on (as evidenced in British Columbia, where 100% revenue return preserved political support for the yearly tax rise), and thus creates powerful price signals that can drive investment, not to mention research and development.

3) The equity argument of needing to refund the tax to consumers, especially low income households, is very important. Using the revenue numbers from your default case, and U.S. Census Bureau numbers for household income distribution, it looks like over $500 billion in dividends would go to households making more than $200,000 a year over the 22 years you modeled out the tax. This is a substantial sum of money going to people that could arguably afford higher energy prices, and whose carbon consumption behavior may not change all that much based on the size of the refund compared to their incomes. What do you think about directing that money to clean energy deployment and other emission reduction efforts instead? I understand the political reasons for giving a refund to everyone. However, are there other technical or economic arguments for not having an upper income cut-off and instead using the revenue for direct emission reduction projects?

I am very interested in your perspective on this point, because it seems that given how late we are in the race to avoid an irreversible threshold to a largely uninhabitable planet, we should be throwing everything we have at the problem. I have a hard time seeing how we can afford to refund such large sums of money to high income households when it could be used to important effect elsewhere. Would it not be worthwhile to vastly expand public transportation, and/or put as many solar arrays on available roof-tops as could be purchased, or keep forests standing rather than recycling revenue to those who likely don’t need it? A $200,000 annual income cut-off for a refund would still shield low and middle income families from energy price increases. Obviously, other income cut-offs could be used, but you get the idea.

I definitely get the idea, and I thank you for the calculation (which I confirmed , probably using the same Census income table as you; it puts 4.2% of U.S. households at or above your cutoff, which I multiplied by the projected $14.8 trillion in cumulative “available” carbon-tax revenue to 2036, to calculate $620 billion.)

My response parallels my answer to Question #2: for me, the value of preserving the structure of the overall arrangement (in which equal per-household dividends of the tax revenue engender public and political support for the tax to keep rising) overrides both my strong personal feelings about economic inequality and my awareness (which I share with you) of the potential payoff from allocating the $620 billion to infrastructure and energy projects that could push down CO2 emissions further. Here I’m particularly concerned with the perceived arbitrariness of an income cutoff. Consider that in just the tenth year of the tax (2023 if it starts in 2014) the per-household dividend will exceed $4,000; in which case a household with an income of $199,000 will make more money, with the dividend, than one with an income of $201,000. Yes, sliding scales could be devised, but these threaten to make the distribution so complex that it becomes vulnerable to other carve-outs which then cascade to a point where it loses its public appeal.

4) Forest loss is a large source of carbon emissions globally. Most of the emissions come from tropical deforestation, but conversion of forests to housing and commercial real estate in the U.S. (and some other management changes) is projected to make domestic forests a net source of emissions by 2030. Allocating a very modest portion of carbon tax revenues to both the U.S. contribution to financing an end to tropical deforestation, and to preventing forest conversion domestically directly reduces CO2 emissions, and has numerous ecological and social co-benefits. Having worked in this particular field for over 20 years, I know that coming by adequate funding for forest conservation is a huge challenge – this is another race we are losing to disastrous consequences. Carbon taxes are being used by other nations, like Norway, to address emissions from tropical deforestation. And Waxman-Markey allocated some auction revenue for forest conservation. Using carbon tax revenue to reduce forest-based emissions, or even increase biological sequestration, also has the advantage of not trading off forest emission reductions for a portion of fossil fuel emission reductions, as occurs under an offset system with cap and trade. I am concerned that if no portion of carbon tax revenue goes to this purpose, there will be few other sources of revenue adequate to the task. Do you have any thoughts on this topic?

Answer: We advocate briskly-rising carbon taxes as a needed corrective to spur low-carbon energy innovation and to encourage renewables and efficiency in a price system that lets them compete fairly. But the same logic that points to the need for a carbon tax to “internalize” the social cost of carbon pollution in fossil fuel prices suggests that payments are needed to assure the continued social benefit of carbon sequestration services by forests and aquatic ecosystems. As you point out, these ecosystems are being diverted to more financially lucrative uses because their climate and other ecological benefits are unpriced. Under “the polluter pays” principle, those who benefit from dumping carbon into the atmosphere should pay for the service of sequestering it safely. And yes, that’s a lot more direct and clear than using offsets under cap-and-trade to fund ecological services.

As noted, we recommend returning carbon tax revenue (either as a tax shift or a direct payment) primarily as a way to mitigate regressive effects and to build the kind of long-term political support we’ve seen for British Columbia’s revenue-neutral carbon tax. But the argument for using at least a portion of the revenue stream to fund carbon sequestration services strikes us as compelling. Several carbon tax proposals suggest allocating funds from harmonizing border tax adjustments (essentially tariffs) on carbon-intensive imports to finance international forestry projects. Under that structure, carbon tax revenue from domestic goods would be “recycled” to households, while the import tariff would fund preservation and restoration of forests and perhaps aquatic ecosystems’ capacity to sequester carbon.

5) Can you briefly describe your confidence in your price elasticity assumptions? I noticed when ramping up the tax in your model, for example to start at $40/ton and increasing it by $20/year, the average rate of emission decline does not respond that dramatically — it goes from 2% up to 2.6% per year. Do you have any sense of the chances that your model might either over or underestimate individual and business reaction to carbon price increases?

Answer: My math yields a somewhat different result. Comparing projected 2036 emissions with actual 2012, and again using compound averages, I calculate a 2.5% annual average decline with the default $15.00/$12.50 tax, and a 3.7% decline rate with “your” $40.00/$20.00. Your tax is roughly two-thirds higher than mine in 2036 and has achieved a roughly one-half greater decline rate, which seems plausible.

Again, though, your broader point is well-taken: the elasticities in the model are merely estimates, not “facts,” and they are particularly uncertain on the supply side, which is the anticipated locus of the decarbonization process under a carbon tax. (In three of the model’s six sectors, a majority of the CO2 reductions come from fuel decarbonization, whereas in only one, air travel, does a majority come from reduced usage; one sector is split 50-50 and reductions in the sixth, natural gas usage in industry and heating, are necessarily all via less usage because natural gas can’t be decarbonized further.)

It does appear that our model is conservative (predicting lower CO2 reductions) than most other models. Perhaps it needs to be more attuned to the extent to which strong, clear price signals will encourage development and deployment of low- and zero-carbon technologies. We hope to explore and explain these differences via further analysis.

Thanks for any time you have to address these questions.

Best,

Paula Swedeen

Thank you for your collegial and thought-provoking questions!

Europe's Carbon Market is Sputtering as Prices Dive

EU Carbon Market Sputters as Prices Dive (NYT)

Time for a Smart Taxpayer Revolution

Guest post by Lindsay Sturman, a writer living in Los Angeles with her family.

We all hate taxes, but we also want and need government services. Rather than raise taxes or cut services, there’s a Third Way that has been overlooked: tax behavior that costs the public money.

“Sin taxes,” or better yet, “Smart Taxes” create a virtuous cycle – the tax raises the price of the product, causing consumption to drop, thus reducing the costly and damaging behavior. It’s Economics 101 – if we raise the price, we’ll get less of the behavior.

It’s unusual in government to have your cake and eat it too – but “Smart Taxes” is one of those rare perfect storms.

It’s unusual in government to have your cake and eat it too – but “Smart Taxes” is one of those rare perfect storms.

Tobacco is a great example, because most people wish fewer of us smoked, especially children. Over a hundred studies have shown that raising the price of cigarettes causes consumption to go down. Smoking also costs taxpayers dearly in health care costs treating Medicare and Medicaid patients for lung cancer, emphysema, chronic pulmonary disease and heart disease. Economists across the political spectrum agree that a pack of cigarettes should be taxed to reflect the true cost to society of smoking so taxpayers are not subsidizing tobacco companies.

Think about it: tobacco companies put out a product that causes disease and death, they make a handsome profit, and society is stuck with a huge bill estimated to cost the U.S. $96 billion a year, according to the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. Economists have a word for the damage: an “externality.” In a perfect capitalist system, the cost of the externality of lung cancer would be captured in the price of a pack of cigarettes.

Carbon combustion is another area that costs us dearly – in higher rates of diseases such as asthma, traffic crashes, tailpipe and smokestack pollution, and the potentially catastrophic effects of global warming. Why should taxpayers subsidize the corporate pollution and the detrimental effects of a product, while the polluters walk away with a huge profit? Let the polluters pay, and let the price reflect the cost.

Along with cigarette taxes, another smart tax in use for decades is alcohol taxes, which cover at least some of the cost of alcohol-related disease and accidents. Along the same lines, a tax on bullets could offset some of the societal costs of shootings – the costs to hospitals, police departments and the court and prison system; this was once a political non-starter, but there is now a growing movement calling for this change. We could also be made better off, economically and health-wise, by taxing sugar and soda consumption that contributes to the marked increase in diabetes and obesity-related diseases; the costs are staggering, with obesity alone costing America a shocking $147 billion a year.

Here are examples of Smart Tax proposals from across the political spectrum:

- Carbon tax — Carbon Tax Center puts revenue in the trillions with a substantial cut in emissions – $1.5 trillion over 8 years.

- Soda tax — 1 cent per what? tax would raise $160 billion over 10 years while motivating 8-10% decline in consumption, lowering our health care costs.

- Tobacco tax— 50 cent per pack rise could raise $80 billion in 10 years (Congressional Budget Office).

- Marijuana tax – In states where legal, could raise $90 billion in 10 years and save the same in reduced law enforcement. Net gain: $180 billion.

By taxing “bads” we can achieve the trifecta: raise money to treat the disease/damage/costs, reduce consumption and thus prevent disease/damage/costs in the first place, and make a dent in health care spending and the cost of government across the board. Not to mention avoiding the incredible suffering these diseases cause – which is the best reason to do it.

Smart Taxes do not have to be a tax increase, but rather a tax shift. For every dollar raised in carbon, alcohol, and tobacco taxes, another tax could be lowered dollar for dollar: payroll taxes, income taxes, business taxes, or sales taxes. Lowering those taxes would encourage the economic activity that we want more of but which our upside-down tax system inhibits. Republicans and Democrats alike agree that sales taxes cut down on sales and payroll taxes impede job growth.

Smart Taxes could motivate the next taxpayer revolution. Whatever our political persuasion, we as citizens need to demand that our elected officials lower taxes on “goods” and raise them on “bads.”

Photo: A.C.N. Photography, via Flickr.

Carbon Tax…Are Republicans Really That Stupid?

Possibly the Stupidest Supposedly Intelligent Anti-Carbon Tax Piece Ever (Forbes)

How "Skeptics" View Global Warming

Graph: How “Skeptics” View Global Warming (skepticalscience.com)

Wood: The fuel of the future

Subsidies Have Made Wood Europe’s #1 Renewable-Energy Source (Economist)

Presenting: An Even Better Carbon-Tax (Spreadsheet) Model

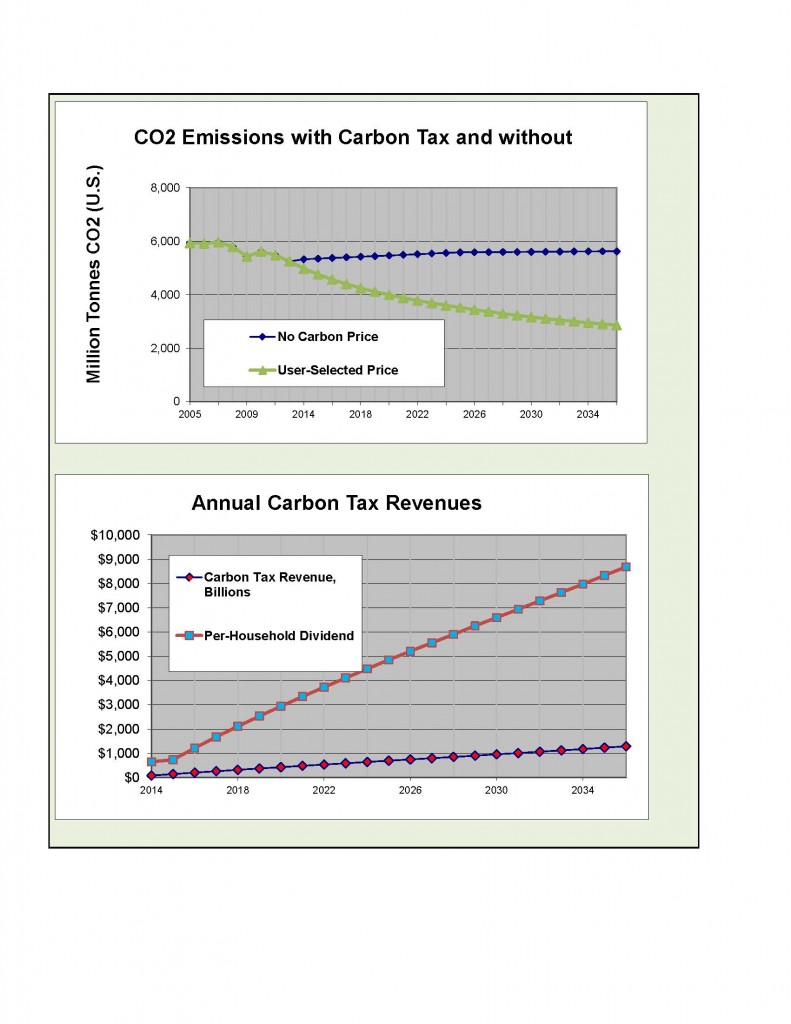

Today we unveil our enhanced carbon tax model. The link on our Home Page takes you automatically to the new version. (You may also download the model by clicking here.)

As before, the model is a compact (600 kB) Excel spreadsheet that runs on PC’s or Macs with Excel 2003 or later. Like prior versions, it splits the U.S. energy-economy into a handful of “sectors” (e.g., electricity, passenger vehicles) and, for each, generates 20-year-or-more projections of usage and per-unit carbon emissions with and without a price on carbon pollution. You can set the prices yourself — we say “prices,” plural, because you can specify both the initial price and the rate of year-to-year increase; or you can use our “out of the box” pre-set prices.

The result is a pair of emissions projections — one with the carbon price and the other without — with both referenced to the same set of anticipated changes in economic activity and energy prices. The difference between the respective projections is the emission savings (reductions) imputed to the carbon tax.

Here are the key new features (these bullet points have been updated to reflect the 2014 version of the model):

- The model is baselined to 2013 levels of economic activity and fuel use. Thus it reflects the dizzying shifts of late in electricity generation shares, from high-carbon coal (which lost six percentage points of market share from 2010) to lower-carbon gas (up four points) and zero-carbon wind (up four points).

- The model employs “official” U.S. forecasts of economic growth, general inflation, and, most importantly, of prices for electricity, natural gas and crude oil, rather than our own forecasts. (The carbon tax is layered “on top of” the official prices.)

- Explicit treatment of inflation. First, the carbon tax itself can be indexed to general inflation, or not; second, energy prices (including the carbon-tax-affected prices) are translated into the nominal (inflation-inclusive) prices in which end-users actually experience (i.e., pay) them. While this may sound complex, the model results are more rigorous (accurate) than before.

- The model has seven sectors, up from five. We’ve split our catch-all category of “Other” energy uses (other than electricity, driving and other personal ground travel, freight movement, and aviation) in two: uses fueled by natural gas, and uses fueled by petroleum products. This enables the model to more fully capture differences in gas and petroleum prices including sensitivities to carbon taxes. A “miscellaneous” category captures CO2 emissions from non-electricity-generation uses of coal; from non-energy uses of fossil fuels such as natural gas used in chemical plants, LPG (liquid petroleum gas), lubricants and naphtha; and fuels used for energy in U.S. territories (which are not included in other tabs).

- We’ve overhauled our derivation of the tax’s impact on petroleum usage. Not only was our previous method needlessly convoluted; it also over-calibrated oil’s shares of the different sectors and thus led to overstating the reductions in petroleum usage from the carbon tax-caused reductions in future energy usage. (The predicted reductions are impressive nonetheless: for the Larson bill, which we model with inflation-indexed prices of $15/tonCO2 in the first year, incremented by $12.50/ton each year, the tenth-year reductions in oil usage are 4.3 million barrels a day from 2005 levels, and 2.6 million b/d from projected oil requirements without a carbon price; for comparison, the Keystone XL pipeline is intended to deliver 0.83 million barrels a day of crude from Canadian tar sands to U.S. refineries.)

- A new spreadsheet tab, Index, has links that improve navigation among the 22 different tabs.

- Clearer graphs of CO2 reductions and petroleum savings, and a new graph of revenue generation, expressed both nationally and per-household.

- Generally improved layout and presentation.

The key result — the model’s estimate of CO2 reductions from U.S. carbon taxes — is largely unchanged from earlier versions. In the tenth year of a “Larson”-type carbon tax, with the carbon tax rates noted in the large bullet-paragraph above, projected U.S. emissions CO2 from fossil fuel combustion are 1.8-1.9 billion metric tons less than predicted without a carbon price, a 33% reduction.

A few tabs in the spreadsheet aren’t yet complete. Nevertheless, the features enumerated here constitute such a large improvement over the prior version to warrant posting it today. We invite all users of the model, old and new, to kindly:

- Update earlier findings you may have drawn from prior versions of the model, substituting results from this one.

- Walk through the model with an eye toward evaluating it for logic, rigor, presentation and functionality. Please e-mail us all suggestions and criticisms, via info@carbontax.org.

Happy modeling, and best wishes.

— Charles

Sunday Dialogue: Tackling Global Warming

EDF’s Wagner Calls for Carbon Pricing (NYT letter)

Getting Serious About a Texas-Size Drought

Extended Drought Gets Texans Thinking Conservation (NYT)

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- …

- 170

- Next Page »