Fabrice Mossé, commander of a team of 109 French firefighters battling climate-charged forest fires in northern Quebec, quoted by New York Times reporter Norimitsu Onishi in ‘The Fires Here Are Unstoppable,’ NYT, June 18.

New York Times congestion-pricing table-setter bodes well for carbon taxing

The New York Times yesterday published my op-ed, There’s Only One Way to Fix New York’s Traffic Gridlock, co-written with Columbia University climate economist Gernot Wagner.

Our essay is a meticulous and extensive (1,300 words) brief for making drivers feel the pocketbook costs of their vehicles’ traffic-jam causation, via the policy measure known as congestion pricing. In our telling, not only is this policy guaranteed to generate immense benefits for New Yorkers; as the title suggests, we declare it to be the only way to “free … drivers from the traffic snarls that pollute the air and crush the soul.”

From the Times’ home page, June 8, 2023.

The essay was nearly a month in the making and the product of extensive argument-shaping and fact-checking by the Times’ op-ed staff, bespeaking the paper’s commitment to presenting congestion pricing in a positive light. Its appearance broke the mold of the paper’s hesitant past coverage in two important respects:

1. It explicitly rests on the “comprehensive spreadsheet model” of New York traffic and transit I began developing in 2007 (coincidentally, the year I launched the Carbon Tax Center).

2. It let Gernot and me voice the inconvenient assertion that the regional transit agency charged with designing and administering congestion pricing — the Metropolitan Transportation Authority — “through a few fateful, faulty assumptions, underestimated drivers’ propensity to switch trips from cars to other transit options.” These flubs have tied congestion pricing advocates in knots, forcing us to rebut objections of environmental justice impacts that don’t stand careful scrutiny, although they understandably resonate with communities that historically have borne hugely disproportionate damages from highways, energy facilities and other polluting infrastructure.

It’s only a modest stretch to view the Times’ twin breaks with tradition as the Grey Lady’s version of Andrew Cuomo’s bombshell announcement in August 2017 that “congestion pricing is an idea whose time has come” — itself a rupture that set in motion passage of the state statute authorizing congestion pricing in March 2019.

They suggest that the Times may be lying in wait for the right political winds to let advocates of carbon pricing make a parallel case with respect to climate. Not that a carbon tax is “the only way to fix America’s carbon crisis” but, rather, that it’s a complementary policy tool to last year’s Inflation Reduction Act, and an essential one to ensure that green energy actually replaces rather than merely supplements use of fossil fuels.

For the benefit of non-subscribers blocked by the Times’ paywall, and also to enable comments as well as add a few graphics, we present Gernot’s and my op-ed in full.

— C.K., June 9, 2023

The plan to charge drivers to enter Manhattan south of 60th Street, which last month moved closer to federal approval, will deliver two notable gifts to New York and the region when it begins, perhaps as soon as next April.

The first is that congestion pricing will cut traffic not just within the so-called charging zone but on the hundreds of streets and highways that cars use to go to and from that zone. This reduction of almost two million miles traveled in the region each day will free many drivers from the traffic snarls that pollute the air and crush the soul.

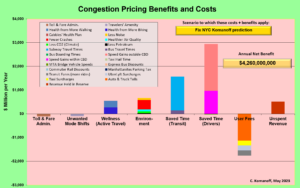

Using a detailed benefit-cost analysis that assumes a pricing structure of $15 at peak times, $10 as traffic begins to thicken and $5 at off-peak times, we calculate that the value of those projected time savings to drivers and truckers amounts to nearly $3 billion a year, with time saved in the boroughs and counties surrounding Manhattan exceeding those on the island.

These estimates are based on a comprehensive spreadsheet model of the region’s traffic, developed by one of us (Mr. Komanoff). State officials used that model to write the statute authorizing congestion pricing, which the New York State Legislature passed in 2019.

The other gift will be the $1 billion a year in congestion pricing revenue that the Metropolitan Transportation Authority will use to secure $15 billion in bonds to pay for improvements to mass transit in the city. Those upgrades will reduce waiting times and onboard delays — and the precious time subway passengers lose as a result.

Either outcome would be a godsend. The combination has the potential to be transformational for New Yorkers.

Our op-ed rests on the benefits and costs summarized in the chart.

Why, then, do many people seem anxious about, if not downright opposed to, congestion pricing? Entitlement plays a part: Why should we suddenly be forced to pay for something that had been free? Another reason surely is disbelief. Many people don’t believe that the revenues — the $1 billion a year from drivers — will actually improve mass transit services. The M.T.A. is a money pit, people say.

They may have a point. But the subway, bus and commuter rail services that the M.T.A. operates are also a marvel and a necessity. After the pandemic lockdowns, the system still delivers 2.5 times as many people a day into the Manhattan core as cars and trucks do, though that is down from four times as many before Covid struck. Still, the M.T.A. must build and manage far more effectively. The same political will that got congestion pricing written into law must be marshaled to eliminate layers of consultants, to bring work rules into the 21st century and to make design-build contracting, in which the project designer and the contractor work together under one contract from the beginning, the rule.

People are also unconvinced that congestion pricing will, in fact, cut congestion. Urban gridlock has come to appear immutable in the United States, perhaps nowhere more so than in the Manhattan core, where travel speeds were averaging a maddening 7 miles per hour before the pandemic. Why should congestion pricing succeed where a century of other remedies — like widening roads to only then narrow them again — has failed?

This question is even more salient after the M.T.A.’s environmental study of congestion pricing, released last summer, which concluded that Manhattan traffic will diminish only because trips that now pass through the city’s center would divert around the island, possibly adding traffic and air pollution to parts of the Bronx, Staten Island, Nassau County on Long Island and Bergen County in New Jersey.

We believe that the M.T.A., through a few fateful, faulty assumptions, underestimated drivers’ propensity to switch trips from cars to other transit options. We don’t say this idly — our estimation is based on decades of studying traffic in and around Manhattan and on basic economic principles.

How much traffic will diminish will depend on the toll design selected by the civic leaders who make up the city-state Traffic Mobility Review Board. They’ll be aiming for the same sweet spot that London, Stockholm and Singapore have attained through their successful congestion pricing programs: 15 to 20 percent fewer car trips into the zone, a cut big enough to reduce the many negatives traffic brings and enough to reap the targeted $1 billion a year in revenues to improve the subways, buses and commuter rail systems. (New Jersey Transit rail and bus and PATH would not share in these revenues.)

The congestion charges have not been set. But the M.T.A.’s model and ours agree that if exemptions are kept to a minimum, it could be as little as $15 for a rush-hour trip into Midtown and $5 to $10 during off-peak hours for E-ZPass holders. (In London, drivers pay 15 pounds during the day, or nearly $19.)

The benefits of congestion pricing — faster, less stressful travel above and below ground and safer, healthier streets and communities — don’t negate the distress of drivers who understandably don’t want to pay where they now drive free, but they assuredly eclipse it.

In addition to the nearly $3 billion worth of saved time for drivers, we estimate that the myriad other benefits add up to an additional $2.5 billion. Those benefits include fewer crashes, better health from cleaner air and more walking and biking, and time saved for transit riders, thanks to improvements enabled by the congestion pricing revenue. Subtracting the $1 billion drivers will pay to enter the congestion zone, the result will be over $4 billion in annual net benefits, or almost $12 million each day.

Moreover, only a small slice of area residents habitually drive into the Manhattan core. Very few are among the working poor, as the Community Service Society of New York, one of the nation’s oldest antipoverty organizations, found when it endorsed congestion pricing in 2019 and again last year. Many drivers, too, may come to feel less of a sting from paying the toll once they actually experience the less-snarled roads.

Schroon River in New York’s Adirondack region on May 12, photographed moments before Gernot called to suggest we pitch an op-ed pegged to the week-earlier removal of a key hold-up to congestion pricing. Our first draft began there.

Last month, the Federal Highway Administration tentatively approved an M.T.A. report that identified how to alleviate possible harm to disadvantaged communities. Now the public has until Monday to review it.

To opponents of the plan, we say:

The M.T.A. is responding to public concerns. To hasten federal approval, the agency has committed to toll discounts for frequent low-income drivers into the zone and also to encourage pollution reductions such as electrifying diesel-powered refrigeration trucks at the Hunts Point Market in the South Bronx and expanding New York City’s clean trucks voucher program to help pay to electrify diesel trucks elsewhere. These commitments followed public feedback on earlier versions of the plan.

Every car is causing congestion. Stalled highways and jammed streets aren’t just the fault of Uber or U.P.S. or bike lanes or public plazas. Everyone driving to or in New York’s central business district (except in the wee hours) adds to congestion. We estimate that right now, a single round trip by car from Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn to Radio City Music Hall in Midtown during most of the day causes $100 to $200 worth of additional delay for everyone else. That makes a prospective $15 or even a $20 peak congestion toll a downright bargain in comparison.

Congestion pricing is the only durable antidote to persistent traffic congestion. The Columbia University economist and Nobel laureate William Vickrey demonstrated 60 years ago that there’s no way out of gridlock without making drivers pay for taking up limited street space. Otherwise, there will always be more car owners wanting to use the available space than there is space to accommodate them.

Drivers all over the city and well beyond stand to gain from this plan. Yes, it will be painful to pay for something that has been free. But it is even more painful to spend hours idling in traffic, knowing that a better path beckons.

Charles Komanoff is a transportation analyst in New York. Gernot Wagner is a climate economist at Columbia Business School.

Fossil fuel divestment is surely one of most useless climate change tactics ever invented. It has had no effect on the companies, or more importantly, the climate. And it never will.”

Veteran journalist Joe Nocera, in Divesting from Big Oil Is an Empty Gesture, The Free Press, June 7.

For Long-Term NY Transit Funding, Look to a State Carbon Tax

The New York City public affairs site Gotham Gazette today published my essay, For Long-Term MTA Funding, Look to a State Carbon Tax. I’ve cross-posted it here to allow comments and to bring it directly to the Carbon Tax Center’s readership.

— C.K., May 4, 2023

That huge sigh of relief from New York City mass transit advocates last weekend was for the state budget handshake to tack more than a billion additional dollars a year onto a key MTA funding stream, the Payroll Mobility Tax. According to both my calculations and an announcement from Gov. Kathy Hochul, the agreed-to 75% rise in the tax rate on employee salaries paid by businesses in the five boroughs will add $1.1 billion to the PMT’s ongoing annual $1.8 billion take.

That huge sigh of relief from New York City mass transit advocates last weekend was for the state budget handshake to tack more than a billion additional dollars a year onto a key MTA funding stream, the Payroll Mobility Tax. According to both my calculations and an announcement from Gov. Kathy Hochul, the agreed-to 75% rise in the tax rate on employee salaries paid by businesses in the five boroughs will add $1.1 billion to the PMT’s ongoing annual $1.8 billion take.

(The numbers prorate imperfectly because the rise in the tax rate, to 60/100 of one percent, applies only in the city; the rate in the seven suburban MTA counties remains 34/100 of one percent.)

The upward bump in the PMT is part of the package to avert a fare hike and service cuts that would have jolted the entire metro region. Raising the same $1.1 billion via the subway farebox, for example, would have required a whopping 35% jump in fares, a calamity that would have triggered enough new car, cab, and Uber trips to slow vehicles in Manhattan by 5% and boosted city and regional carbon emissions by nearly 400,000 tons of CO2 a year — enough to negate the climate benefit of 90 new large wind turbines, according to my modeling. And these figures don’t include lost jobs and commerce from worsened transportation. Reducing service to save the same amount would have produced similar bad outcomes.

Score a big win, then, for transit and New York. But the new revenue comes with a downside: taxes on payrolls discourage hiring and compound our area’s anti-business aura. Moreover, this revenue infusion will almost certainly be not the last but the first in a series the MTA will require throughout the decade to limit future fare hikes and improve service even as ridership continues to lag pre-pandemic volumes. Counting on raising the PMT next time, and the time after that, will be a fool’s errand. There has to be a better way.

I believe there is: enact a modest statewide carbon tax and dedicate a third to a half of the revenue to shoring up public transportation budgets around the state, though principally in New York City.

Reappraising Carbon Taxes

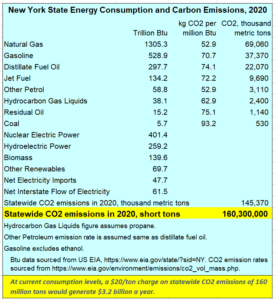

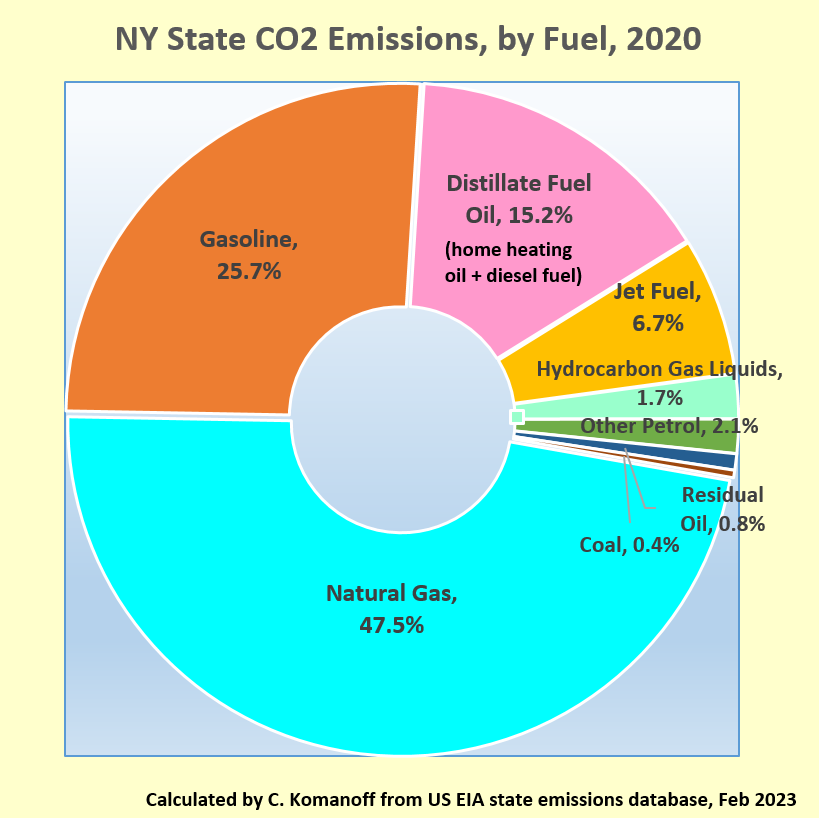

On January 1, Washington state launched its carbon-pricing program, the nation’s second all-sectors carbon charge, with a starting price around $20 per ton of CO2, though most of the emission allowances fetched even higher prices in the first carbon auction, in March. I estimate that the same $20 price applied to all fossil fuels burned in New York State could generate revenues of $3 billion a year (see table).

Dedicating a third of those proceeds to the MTA would add a billion dollars to the authority’s annual revenue. Other slices of the revenue could cure deficits at smaller transit systems around the state.

Dedicating a third of those proceeds to the MTA would add a billion dollars to the authority’s annual revenue. Other slices of the revenue could cure deficits at smaller transit systems around the state.

Even with these allocations, roughly half of the new $3 billion in annual carbon revenues would remain available for a range of purposes from home weatherization to rebates offsetting higher fuel costs for lower-income rural New Yorkers.

Of course, no new tax is ever welcomed with open arms. In recent years, moreover, carbon taxing has lost political standing with left and right alike. Right-wingers, in thrall to fossil fuels, denigrate the very idea of climate concern. Opinions on carbon pricing on the left, while far more nuanced, tend toward an “eat your peas” quality, seeing the promised revenues but not the powerful tides unleashed by the increased fuel prices.

Could a state carbon tax have a chance in New York this time around? I believe so, if only because MTA deficits are untenable and a statewide carbon tax looks like the least-bad long-term antidote.

Consider:

- New York wouldn’t be the first state to price all carbon emissions. California has done so for a decade, and, as noted, Washington just followed suit.

- Two-thirds of the $3 billion in carbon tax revenue could go to other, non-MTA uses across the state.

- Nearly half of the revenues would come from charges on fossil (natural) gas, the very fuel that climate activists are targeting in order to electrify heating and cooking while also shrinking climate-damaging methane leaks from pipelines, wells, and buildings.

- Carbon taxing’s regressive bias (it takes more dollars from the rich but more proportionally from the poor) would be blunted by its helping keep a lid on transit fares.

- The affluent suburban counties that will be on the hook for the carbon tax caught a big break by their exemption from the increase in the Payroll Mobility Tax. Moreover, some pro-climate suburbanites might even support a climate-helping carbon tax.

- Upstate households will be cushioned from the tax by the region’s preponderance of low-carbon electricity from nuclear, hydro, and wind power.

- Aid to transit could be packaged as an urban corrective to suburban- and rural-facing Inflation Reduction Act federal subsidies for solar panels, electric vehicles, and heat pumps. (Notably, the IRA does not fund urban-friendly mass transit and e-bikes.)

- Left-leaning climate-justice advocates who shy away from carbon pricing might warm to a policy that cuts emissions by attracting car trips to buses, trains, and subways.

This panoply of advantages points to diverse potential sources of support for a transit-benefitting state carbon tax:

- NYC transit and “livable streets” advocates;

- Economic-justice advocates who recognize affordable transit’s value in combating poverty;

- Climate campaigners who see carbon pricing as a complement to other carbon-cutting policies;

- Suburbanites concerned that future hikes in the Payroll Mobility Tax will come for them;

- “Electrify-everything” proponents working to eliminate fossil gas from residences and other buildings;

- Developers of low-carbon electricity — not just solar and wind providers but proponents of retaining the state’s four upstate reactors and building new ones;

- Energy-efficiency engineers, contractors, and workforces;

- Labor unions whose members fabricate, erect, and maintain the spectrum of green energy projects that a carbon tax will help make more abundant by making fossil sources costlier.

Competing Claimants?

Electricity producers in New York already pay a carbon fee under the multi-state Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) cap-and-trade program. In addition, Governor Hochul and the statewide climate coalition New York Renews have advanced competing carbon pricing concepts, both of them, somewhat confusingly, dubbed cap-and-invest. Hence, an MTA-focused carbon tax, which would employ a carbon-based charge on fossil fuels extracted or imported into New York State rather than a carbon cap enforced through sales of emission permits, wouldn’t arrive on a blank slate.

RGGI currently charges electricity producers around $14 for each ton of CO2 their generators emit. This levy is generating $365 million of statewide revenues a year, paid as surcharges on power bills, which goes to support investments in energy-efficiency and renewable electricity. While in theory the RGGI charge could be netted against the new carbon tax, the relative ease and importance of decarbonizing electricity production make it preferable to retain it and add the carbon price on top.

RGGI currently charges electricity producers around $14 for each ton of CO2 their generators emit. This levy is generating $365 million of statewide revenues a year, paid as surcharges on power bills, which goes to support investments in energy-efficiency and renewable electricity. While in theory the RGGI charge could be netted against the new carbon tax, the relative ease and importance of decarbonizing electricity production make it preferable to retain it and add the carbon price on top.

Cap-and-invest presents a trickier set of issues, partly because neither the governor’s prospective program included in the new budget nor NY Renews’ more elaborate plan has been fully fleshed out. In addition, the latter is the fruit of years of deliberation and consensus-building among the coalition’s hundreds of participant grassroots groups, who now constitute a formidable host.

At this writing, NY Renews envisions applying $10 billion in carbon revenues over several years in no less than 73 individual spending buckets grouped in four uber-categories: Climate Jobs and Infrastructure includes elements like aiding electric bus manufacture ($100 million) and offshore wind power supply chains ($300 million). Energy Affordability earmarks $1 billion to wipe out utility customer debt and $2 billion to support building electrification. Community & Worker Transition Assistance devotes $600 million to the “just transition” from jobs in carbon fuels to positions in renewable energy. And Community Directed Climate Solutions sets aside $2 billion to unspecified projects in historically underserved and overburdened urban neighborhoods and rural areas.

The NY Renews plan should be seen, then, as a holistic roadmap to make over not just how energy is supplied in the state but how it is consumed and governed. Billion-dollar-a-year allocations to the MTA aren’t the kind of investment its members have envisioned. Nevertheless, exploratory calculations suggest that the carbon payoff from service improvements paid for by a state carbon tax would be impressive.

As an illustration, I have calculated that an average 20% speed-up in subway trips achieved by running more trains at higher speeds would save straphangers and drivers each around 100 million hours a year (the latter from car trips switching to trains) while reducing car and truck emissions by 900,000 tons a year. Even more CO2 would be eliminated because of New York City’s improved competitive advantages vis-a-vis less “inherently green” suburbs and exurbs.

To be sure, so striking a gain in subway performance would almost certainly carry a price tag well over a billion dollars a year. Still, the prospective benefits underscore both the carbon-cutting potential of infusing new funds into subway service and the need to score competing claims for their climate value.

Broader Considerations and Next Steps

Over time, the carbon tax’s revenue base will shrink as its price incentives kick in and other carbon-cutting policies also gather steam. The resulting loss in tax revenues could be counteracted by periodically raising the per-ton tax rate. New York City could supplement the tax through revenue-generating street-management measures such as curbside pricing and other forms of road pricing.

Earlier this year, Community Services Society CEO (and MTA board member) David R. Jones and Riders Alliance executive director Betsy Plum proposed expanding New York City’s Fair Fares program to allow an additional 772,000 lower-income New Yorkers to qualify for half-fare transit passes. The cost, which they put at $142 million a year, should be a candidate for the carbon spending package.

This discussion has centered on the carbon tax’s creation of a new funding pot to maintain and improve transit affordability and performance. But taxing carbon emissions stands to benefit society in two other major ways. It will diminish financial incentives propping up carbon fuels and also support societal paradigms promoting care over harm.

A carbon tax is more than just a pay-for, in other words. Simply making it more expensive to buy and burn carbon fuels discourages fossil fuel use in a multiplicity of ways. Moreover, the very act of pricing carbon emissions can spur “externality taxing” in other realms, from congestion pricing to taxing the sugar content of soft drinks. Making New York the third U.S. state with broad-based carbon pricing will also add momentum to long-sought federal carbon emissions pricing.

Shoring up MTA finances, while reason enough to enact a state carbon tax, isn’t the lone consideration. The crisis of transit funding should be seen as a catalyst to pricing fossil fuels more closely to their true societal costs — a vital goal in its own right.

The next MTA funding crisis-as-opportunity will be upon us soon. The Legislature should move swiftly to study the benefits of taxing carbon emissions as a way to hold the line — and more — on transit fares and service, well in time for next winter’s budget negotiations. Transit and climate advocates and their counterparts in the Hochul administration should consider integrating a transit-focused carbon tax into their agendas.

Taking $3 billion a year for any public purpose, no matter how noble, is no small matter. The time to start selling a transit-supporting state carbon tax is now.

Fossil fuel companies are producing something that society has been eagerly gobbling up. We have to drastically reduce demand.”

John Holdren, chief science advisor to Pres. Obama (2009-2017), in New York Times, Many Young Voters Bitter Over Biden’s Support of Willow Oil Drilling, April 25. The article, by climate reporter Lisa Friedman, added that Holdren “opposed the Willow project. But he believes that driving down the demand for oil and gas — as the Biden administration is trying to do by expanding clean energy and encouraging electric vehicles — is more effective than blocking drilling. If everyone is driving electric cars, there’s less need for gasoline, the theory goes.”

A Bitcoin Mining Exposé Strengthens the Case for a Carbon Tax

The Nation magazine this morning published my essay, A Bitcoin Mining Exposé Strengthens the Case for a Carbon Tax. I’ve cross-posted it here to allow comments and add tables and graphics.

— C.K., April 20, 2023

Clean electricity, the backbone of the Biden administration’s strategy for slashing carbon emissions, is becoming daunting to expand.

US wind farms, which last year generated more electricity than all hydropower and solar panels in the 50 states combined, often face years of contention. The entire mid-Atlantic offshore region, an area brimming with wind potential, could be proscribed by Pentagon fretting over interferences with aircraft deployment, Bloomberg News disclosed this week.

But if red tape for green power is a bother, why not get the benefits with none of the fuss? Send commando teams to the 34 large-scale Bitcoin mining sites in the United States that were identified in a New York Times front-page exposé this month. In synchrony, have them sever the facilities’ power cables, which combined demand some 3,900 megawatts of electricity—nearly as much as 3 million households combined.

In a flash, legions of electricity-gulping, combination-seeking computers in Texas, New York, and 13 other states would cease whirring. Like a power surge but in reverse, the fossil-fuel generators energizing so-called cryptocurrency mining—literally, trillions of combination-seeking calculations every second—would dial down. The corresponding drop in carbon emissions would be the same as if thousands of new industrial-size wind turbines could be instantly erected and connected to grids, supplanting electricity now furnished by burning coal and methane gas.

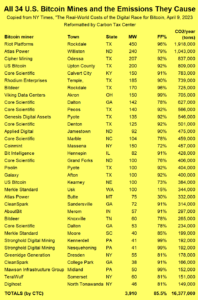

Data adapted from NY Times April 9, 2023 story. Link in text above. FF% is estimated percent of *incremental* power demand supplied from coal or methane gas.

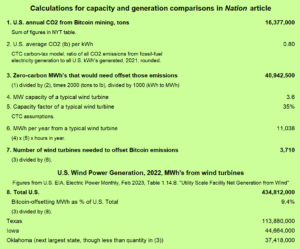

Fanciful? Consider the numbers. The Times helpfully enumerated each Bitcoin mine’s fossil-fueled draw on state and regional power grids along with the associated carbon emissions. It took only a few further steps for me to translate those emissions into generic megawatts of clean power that would defray them. Using today’s customary 300-foot-tall, 3.6-megawatt wind machines as my standard, I calculated a staggering 3,700 turbines.

There you have it: The US Bitcoin industry is single-handedly neutering the entire climate benefit from nearly 10 percent of US wind energy. That’s more electricity than is generated with wind in any single state, save Texas and Iowa.

This raises two uncomfortable questions for the climate movement: Why isn’t it rallying against Bitcoin mines and other parasitic users of carbon fuels? And why isn’t it taking the obvious step of calling for a tax on carbon emissions to reduce those usages while simultaneously extracting revenues from them?

Second question first. Generating the electricity consumed by those 34 Bitcoin mines causes 16.4 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions each year, according to the Times. If the United States had a $100 per ton carbon tax—the current price of carbon emission permits in the European Union’s cap-and-trade system—the carbon levies at the mine mouth and wellhead would be extracting $1.5 billion a year from the fossil fuel companies that power the Bitcoin operations, and depositing it into the Treasury.

To be sure, that money would only fund a mere 2.4 hours of federal spending a year—barely a single baseball game’s worth, under the new hurry-up-and-pitch rules. On the other hand, the tax moneys are twice what Fox News will pay Dominion Voting Systems under the settlement reached this week. And they’re recurring.

But it would not be extinguished. That’s where the climate movement comes in.

But it would not be extinguished. That’s where the climate movement comes in.

Had the tax been in place a decade ago, as I and others urged, the extra expense might have stopped some cyber-currency ventures from the git-go. But if it were put into place today, a robust carbon tax could at least impel Bitcoin miners to economize on electricity, charge more for transactions, or actually contract with greener power providers rather than merely pretending to, as the Times found.

Although no one can pinpoint precisely how a carbon tax would shrink Bitcoin mining’s carbon footprint, let alone any single sector’s, abundant empirical evidence suggests that total US carbon emissions would be around a third less with a triple-digit national carbon tax than without. Bitcoin would not be exempt.

The movement has targeted banks and pipelines for more than a decade, with not much to show in the way of lesser carbon emissions. Why isn’t it disrupting Bitcoin mining and other bloodsucking machines—helicopters, private jets, yachts, super-sized SUVs—that feed on fossil fuels and are predominantly playthings of plutocrats? Why isn’t it going all out to stop highway expansions and eliminate restrictive zoning that lock in energy waste for generations?

Yes, climate activists stopped Keystone XL. They won a ban on fracking in New York. They’re fighting to drive oil drilling out of Los Angeles. Valiant, heroic work. But these and other keep-it-in-the-ground victories are creating little climate benefit. Why? Because the same underlying demand, largely unaffected by those protests, is met by supplies from elsewhere.

The bank protests seem even less focused. Conoco doesn’t need financing from JPMorgan Chase or Wells Fargo to drill in the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska. The only “bank” it requires is the collective fuel tanks of America’s 280 million motor vehicles, plus aircraft, off-road vehicles, and pleasure boats.

The bank protests seem even less focused. Conoco doesn’t need financing from JPMorgan Chase or Wells Fargo to drill in the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska. The only “bank” it requires is the collective fuel tanks of America’s 280 million motor vehicles, plus aircraft, off-road vehicles, and pleasure boats.

Marching on Citibank does send a message, and activating seniors who might otherwise sit at home posting about their grandkids is soul-stirring. But if divestment and bank-shaming were going to slow the assault on climate, we would have seen bigger results by now.

“If the world wants to limit warming,” Norwegian energy researcher Espen Erlingsen told the Times this month, “it will have to limit demand for oil and gas because [the] industry can deliver this kind of volume for many more decades.”

Amen. The climate movement’s strategy isn’t working. Trying to bottle up supply instead of throttling demand is whack-a-mole without end, chasing after but never stopping capitalism’s dynamism from erupting in crypto mining and 1,001 other climate-destroying products and technologies.

By itself, a carbon tax won’t cure that. But it would at least start to steer innovation and cultural norms away from endless new climate horrors.

As Philip Roth’s Mickey Sabbath might have said: Either tax carbon or bring on the commandos.

Addendum: My concluding sentence — perhaps too subtle a literary reference — is elucidated in Brian A. Oard’s delightful Mindful Pleasures website. Please note that the ultimatum was uttered not by Sabbath but by his lover, Drenka. — C.K.

If the world wants to limit warming, it will have to limit demand for oil and gas because [the oil] industry can deliver this kind of volume for many more decades.”

Espen Erlingsen, a partner at the research firm Rystad Energy, in “Even as Nations Push Renewables, Oil and Gas Projects Come Roaring Back,” New York Times, April 6. (Headline in digital edition: It’s Not Just Willow: Oil and Gas Projects Are Back in a Big Way)

Climate Sound and Fury, Signifying What, Exactly?

(This post was amended on March 31 to include rebuttals of our criticism of the Montana climate-change lawsuit from two distinguished participants.)

Climate agitation was much in the news last week. The Guardian reported on a forthcoming Harvard Environmental Law Review paper suggesting that fossil fuel companies could be held liable for homicide from deaths caused by climate change. A New York Times front-page story previewed a courtroom trial to determine if Montana policies promoting fossil fuels violate that state’s constitutional protections of a healthful environment. And in dozens of cities, activists assembled by noted climate author-organizer Bill McKibben tore up their Chase, Citi, Wells Fargo and Bank of America credit cards to spotlight the big banks’ financing of $1 trillion in fossil fuel projects over the past five years.

In other climate news, however, suburban legislators are contesting a bold initiative from New York Gov. Kathy Hochul to compel New York City and surrounding counties to expand housing supply. New York City’s public transit provider is scrounging for revenues to shore up declining subway and bus farebox receipts stemming from the triple-whammy of residual Covid worries, violent-crime fears, and working-from-home. Around the country, meanwhile, just about all of the gargantuan road-widening projects listed in U.S. PIRG’s most recent Highway Boondoggles report are proceeding apace.

“States’ rights” have become “local control.” L: Wallace for President rally, 1972, courtesy Google Images. R: Ryan Lowry for the NY Times, accompanying March 22, 2023 opinion essay, “NIMBYs Threaten a Plan to Build More Suburban Housing,” by Times editorial writer Mara Gay. Photo was captioned, “Legislators protested Gov. Kathy Hochul’s housing plan in Albany on Monday.” Faces and demographics in the two photos, taken more than half-a-century apart, are hard to distinguish.

Yes, we’re juxtaposing.

The three just-noted happenings threaten to lock in place profligate fossil fuel consumption and associated carbon emissions. Highway widenings engender more driving (“induced demand,” it’s called). Fare hikes and service cuts to transit in NYC and elsewhere will do the same. And bottling up housing supply, as New York’s suburbs and my own borough of Manhattan, along with affluent cities and towns all over the U.S. have been doing for decades, guarantees urban stasis and its evil twin of exurban sprawl, with its accoutrements of carbon-spewing SUV’s, manses and subdivisions — not to mention segregation.

Litigating for Climate

These carbon accelerants might be more bearable if the climate agitation mentioned at the top had genuine prospects for cutting emissions. Do they? Not likely.

Indicting, much less convicting, officers of fossil fuel companies for killing people via their emissions-induced climate change is the definition of quixotic — to my untutored eye, anyway. In court, Big Oil will simply point to the tens of billions of lives uplifted by the fruits of their fuels. And they won’t be spouting nonsense. The raising up of most of humankind out of subsistence, and the resulting cradle-to-grave lengthening of human lifespans, could not have happened without the carbon-fueled Industrial Revolution. Set against those numbers, the millions — if that — of lives provably lost because of climate change will appear as a mere rounding error.

To be sure, the still-rising use of fossil fuels globally has now burst past the point of positive net benefits, especially with the advent, at last, of scalable non-carbon ways to power civilization. But actually effectuating the transition seems a matter for politics, with or without judicial support.

And even if some clarion guilty verdict were rendered in some court, what would be the remedy? Would the fossil fuel industry be made to dismantle itself? What about the billions of motorists, manufacturers and other consumers and producers who would clamor for more. Sorry, there’s no bypassing the messy work of using pricing, regulation and innovation to get off fossil fuels.

I’m almost as skeptical re the Montana litigation — notwithstanding the earnestness of the young plaintiffs, including two brothers who not only are the sons of firearms-industry apostate Ryan Busse but who were motivated to join the lawsuit by the climatological deterioration of their beautiful corner of northwest Montana.

I identify with Lander and Badge Busse. Melting snow in nearby Glacier National Park helped trigger my ecological awakening, but in an opposite fashion from theirs. On a long-ago day in July, driving on the park’s Going-to-the-Sun Road with my grade-school pal, I parked our tiny Renault auto to fetch water dripping from roadside snowbanks. We filled our canteens and started walked uphill toward the source. An hour later, we were a thousand vertical feet above the roadway and following real-life mountain goats under an impossibly blue sky. Bookending our hike into the Grand Canyon a week earlier, that day became my gateway into love of wildness, defense of clean air, and a career in environmental policy analysis and activism.

Most of Glacier’s glaciers are now diminished if not gone, making the lawsuit, Held v. State of Montana, painful as well as valiant. Yet even if the brothers and their co-litigants win their case, what exactly is the remedy? The Montana Supreme Court possesses no magic button whose pressing can end the burning of fossil fuels. Stop drilling or mining in Montana, and producers will up their output from Wyoming. Stop it in all 50 states, and the same suppliers will boost production overseas. Sure, impeding fuel extraction will incrementally drive up fuel prices and take a bite out of demand, but that’s just a sideways blow at best. The solution, as CTC has argued since our founding in 2007, lies in throttling demand for carbon, not stoppering supply.

Montana litigation supporters weigh in

Shortly after this post went up, CTC received this brief rebuttal from a long-time supporter of the Montana suit and the larger Our Children’s Trust campaign to enshrine a legal right to a safe climate:

The Montana climate suit seeks to build case law affirming a right to a stable, livable climate. I liken it to the long-term legal struggle to secure equal treatment under the law for women and people of color. For example, the legal battle to desegregate schools was a long one built on case law. I agree that any individual state has limited ability to impose a price on emissions, but the Juliana vs. U.S. suit does. It seeks a science-based reduction in emissions sufficient to maintain a stable, livable climate, and proposes a carbon tax as the single most effective policy to achieve that goal. Likely the courts will only impose emission reductions. Politicians will then be tasked with submitting a plan that is affordable and effective. The Montana and other suits build case law affirming the damage caused by fossil fuel emissions and a right to a livable climate. Courts act more on evidence and less on short-term political pressure.

We also received this note from noted environmental attorney and climate-law expert Michael Gerrard, who directs the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School and was featured in the New York Times story noted at the top of this post:

I think we need to attack both the demand side and the supply side. No one action will affect the supply on a macro scale, but cumulatively many could. Montana is one of the nation’s largest fossil fuel suppliers, and if the courts shut down some of that, it would be a good thing. The judge, at least, is taking the case seriously. Whether or not the Montana Supreme Court upholds a decision for the plaintiffs, the case will cast a harsh light on the fossil fuel companies. Most of these campaigns are largely aimed at delegitimizing the fossil fuel companies and reducing their political clout. That is having some effect in blue states, where quite a few strong climate laws are being enacted over the opposition of the fossil companies. And keep in mind that each new coal mine, each new gas-fueled power plant, and so forth, creates a constituency for its long-term preservation; that needs to be resisted.

CTC collage from two separate photographs on Third Act website, snipped on March 30, 2023.

Banks and Climate

We come now to last week’s bank protest that Bill McKibben organized with his new “Community of Americans,” Third Act.

As much as I admire Bill’s unflagging zeal and his Third Act cohorts’ earnest willingness to put themselves out there, I strongly question targeting banks as a cause of fossil fuel exploitation and a locus for climate activism.

How will bank reformation impact the use of cars, trucks and planes in the U.S. or elsewhere — use that requires purchases of gasoline, diesel and jet fuel that in turn provide both the financial wherewithal and the political muscle to drill, extract, refine and transport petroleum products whose combustion releases the carbon dioxide that is wrecking our climate?

Should not Third Act and indeed the entire climate movement be organizing and demonstrating for demand-cutting policies and developments such as mixed-use and dense housing, functional-or-better public transportation, bikeable and walkable streets, fuel-economy standards without “light truck” loopholes, and the like? Wouldn’t their energies accomplish more, both short- and long-term, if they were to swarm Albany and other state capitals to demand upzoning, no more highway widenings, and permitting reform to circumvent anachronistic regulations hindering wind farms and solar homes?

In response, Bill would probably say “We need to remind people of the connection between cash and carbon. Literally, somebody who has $125,000 in those banks [Chase, Citi, Wells Fargo, Bank of America] is producing more [carbon] because it’s being lent out to pipelines and frack wells than all the cooking, flying, heating, driving, cooling that the average American does in a year. Five thousand dollars in [those banks] produces more carbon than flying back and forth across the country.”

How do I know? Because that’s exactly what he said on Democracy Now on the morning of the protests (quoted segment begins around 37:45). Try as I might, I can’t follow the logic.

Coda

Notice I haven’t mentioned carbon pricing, except tangentially. Here at CTC we’re laying low on carbon taxing for the time being. U.S. politics still aren’t ready, what with climate-averse Republicans occupying half of Congress, and Democrats wary of the difficult politics. We focus on what’s possible in the here-and-now.

Last year it was the praiseworthy (if imperfect) Biden-Schumer Inflation Reduction Act. This year we’re continuing to do what we can to bring congestion pricing for New York City into being. We’re also quietly nurturing a promising new avenue to advance a New York State carbon price. Please stay tuned!

Alaska oil push shows Biden lacking courage of his climate-policy convictions.

President Biden’s decision this week to greenlight ConocoPhillips’ $6 billion Willow oil-and-gas drilling venture on Alaska’s North Slope is being cast as a climate disaster first, an ecological disaster second.

That’s backwards, not to mention incomplete. As we explain below, climate damage may be the least consequential aspect of Biden’s decision. More dire is the ecological impact, which will be felt both in Alaska and on America’s roads. But first and foremost, the president’s action is a political debacle.

Biden’s naked, unnecessary expansion of U.S. petroleum extraction into the country’s largest tract of undisturbed public land cuts the legs out from his singular legislative accomplishment so far: the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022.

The IRA’s most public-facing part is its intricate array of consumer subsidies and manufacturing incentives to hasten replacement of America’s two hundred and eighty million petrol-burning cars and trucks with electric vehicles. The Carbon Tax Center came out swinging for this initiative, notwithstanding its tacit endorsement of EV giantism and cold-shoulder of small, urban-appropriate electrics such as bicycles, scooters and neighborhood electric vehicles.

With his Willow go-ahead, Biden has enshrouded the IRA’s proud optics behind a dark curtain. Why direct tens of billions of taxpayer dollars to ramp up electric vehicles, possibly turbocharging U.S. deficits and inflation, if EV’s aren’t going to bring down the curtain on U.S. oil consumption?

Our view is that the “climate bomb” isn’t any one oil project or even all of them, it’s the SUVs, pickups and oversized roads that make the oil business so profitable. Photo credits: L, Kendra Brock / @kendrarayee via Pinterest. R, Riley Rogerson accompanying her Jan. 10, 2023 Anchorage Daily News story, “Protesters rally at White House calling administration to block Willow oil project in Alaska.”

Yes, the combustion-to-electricity transition can’t happen overnight. But Willow makes the transition look depressingly distant. Indeed, by pumping up the supply of the fossil fuels the IRA professes to replace, Biden is casting shade on the underlying paradigm to electrify not only vehicles but “everything,” including heating, cooking and industry.

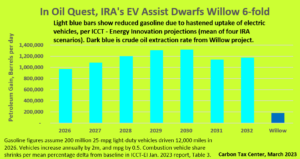

By our calculations, the drop in oil consumption from the IRA’s EV incentives will outweigh the oil supplied from Willow 6-fold. That finding highlights either how big a deal the IRA is or the relatively smallness of the oil venture. But the public is unlikely to see it that way. Rather than viewing Biden’s legislation as transformative, they’ll regard it as banal — helpful, but incomplete without a big assist from business-as-usual fossil fuels.

The “climate bomb” fallacy

CTC has long looked askance at climate campaigns targeting “fossil fuel infrastructure.” We view oil and other fossil supply as the tail, with the carbon dog being the demand that creates both the impetus and the financing to pull fossil fuels from the ground, process them and deliver them to vehicles, engines and furnaces. Stop this well or that pipeline, we contend, and another will be developed to supply the fuels that customers demand.

Yes, this view is oversimplified, but not by much. It is true that each new supply increment pushes down prices somewhat, which then pumps up demand; or, equivalently, bottling up particular supply projects raises industry costs, hence prices, which depresses demand. But these processes are largely indirect and not nearly “one-for-one.” The larger truth, we believe, is that demand finds a way to create supply.

Stop Willow, in other words, and the Permian Basin or the Persian Gulf or emerging oil frontiers like Uganda will serve up replacement supply.

In our telling, then, the only way to stop carbon combustion and climate chaos is to destroy demand. That points straight to carbon taxing, since it directly depresses consumer demand for energy, period, while also engendering conversion of energy supply to low- or zero-carbon sources, particularly in the more fungible electricity sector. Carbon taxes also “play well” with other policy instruments, reinforcing efficiency and regulatory standards.

Accordingly, the true “carbon bomb” isn’t Biden’s Willow signoff nearly as much as America’s 280 million combustion vehicles along with jetliners, helicopters, jet skis and so forth and — to go deeper — the development patterns and acculturation that valorize them. For its part, Willow won’t actually “bomb” Earth’s climate since without it, the same amount of extraction will be done elsewhere (if a tad less fuel-intensively in non-Arctic, non-wild environs).

Alaska’s wild ecosystems and heritage, including Indigenous livelihoods, will arguably be bigger losers than climate, then. Another loser will be our nation’s streets and roads and those who use them, since each opening of the petroleum spigot enables and normalizes the ongoing shift to ultra-large vehicles — both combustion and electric. As urban researcher-scholar David Zipper has shown, the supersizing of the U.S. vehicle fleet is the #1 reason that U.S. road deaths, especially but not exclusively of people riding bicycles and walking, have shot up in recent years even as virtually all other developed nations enjoy steady declines in per-capita traffic fatalities.

IRA vs. Willow: No Contest

The depressing irony about Biden’s approval of the Willow project is that the oil supply it will unlock, an estimated 180,000 barrels a day of crude, according to AP, isn’t particularly large, in oil terms. Notwithstanding the “massive” tag applied in much of the media, ConocoPhillips’ projected output amounts to only 1 percent of 2021 U.S. consumption of 19.8 million barrels of petroleum products per day.

What’s more, Willow’s increment to U.S. supplies will only be one-sixth as much as the need for petroleum that Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act will obviate by accelerating the uptake of electric passenger vehicles vis-a-vis the baseline pace, i.e., more gradually rising EV sales and use without the incentives in the IRA.

This finding is shown graphically at right. To derive it, we relied on projections in a January, 2023 white paper, Analyzing the Impact of the Inflation Reduction Act on Electric Vehicle Uptake in the United States, prepared jointly by two respected think tanks, International Council on Clean Transportation and Energy Innovation.

The calculation was straightforward. Table 3 of the report shows the ICCT/EI projections of future U.S. electric vehicle shares — not of sales but of registered vehicles in use — under baseline assumptions (no IRA) and four scenarios reflecting different extents of consumer uptake of EV’s. We used the “deltas” (differences) from the base case during the seven years of greatest policy impact, 2026-2032 — they average 19 percent — to compute the gasoline that would be burned nationwide if there were no IRA and the IRA-boosted electric vehicle-miles were instead driven in combustion vehicles.

We assumed 200 million passenger cars averaging 25 mpg and each traveling 12,000 miles per year in 2026, with the number of vehicles rising by 2 million a year and fuel economy inching upward by 0.5 mpg per year, but with no change in per-vehicle miles driven. The amounts of avoided gasoline are easily calculated.

Several simplifying assumptions were involved:

- We assumed no offsetting petroleum consumed in generating electricity, due to oil’s minuscule share (less than one percent) of national electricity generation.

- Though ICCT/EI’s deltas don’t apply to states that adhere to California’s more-aggressive zero-emission vehicle rules, we extrapolated them to the entire country.

- We ignored the IRA’s accelerating effect on electric truck sales and use — almost certainly understating the legislation’s petroleum savings more than our overstatement in bullet #2.

- We implicitly treated crude oil supply with gasoline demand, a minor simplification that we suspect doesn’t tilt our comparison much one way or the other.

Tongue-tied on the campaign trail?

From R. Crumb’s, “Despair” Comics, 1969.

We don’t mean to be cruel, but until this week we pictured President Biden campaigning for re-election and touting the Inflation Reduction Act’s manifold achievements: Without a single Republican vote, we passed a law freeing us from manipulated, volatile oil prices and corporate despoiling of our climate and our Earth. And the law is creating millions of good-paying jobs for Americans, especially in areas ravaged and ruined by fossil-fuel development.

That’s still true. But with Willow, the purity of the message is gone, taking much of the power with it.

We allow the fossil fuel industry, economists, politicians, celebrities, random people on the internet, the youths that are leading the climate movement — everyone has a stake and a right to comment on these climate policies except, it seems, those of us who have subject-matter expertise in the area. That seems like an odd policy and I take issue with it.”

Earth scientist Rose Z. Abramoff, interviewed on “Democracy Now” about being fired from her research job at the federal Oak Ridge National Laboratory for her public-facing climate protests, Jan 19, 2023 (quote begins at 54-minute mark).

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- …

- 170

- Next Page »