It should have been big news: A report this month from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency admitted that the fuel economy of new light-duty vehicles sold in the U.S. last year was no better than the year before. The mix of cars, SUV’s and pickups sold in 2021 averaged the same crummy 25.4 miles per gallon as in 2020.

Screenshot from ACEEE Dec. 12 press release. Link is in text.

Flatlining new-vehicle mpg is bad news. It portends more climate damage, worsened pollution and strained household budgets, along with geopolitical turmoil, fattened oil company earnings and brawnier petro-states. It’s also a betrayal of long-standing promises by Democratic presidents, EPA administrators and environmental groups that, together, they would make auto companies achieve ever higher mileages, like 54.5 mpg in 2025, as the Obama administration pledged a decade ago. (See White House 2012 press release, below.)

What happened?

Don’t just blame the Trump administration’s four-year mpg slow-walk and roll-back. The American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy was forthright in its Dec. 12 press release: EPA Finds No Progress in Vehicle Efficiency as Automakers Sell More Big Models (emphasis added).

“The [auto] manufacturers are canceling out all the efficiency progress as they sell more large vehicles,” said ACEEE senior transportation researcher, Avi Mersky. “And it’s completely allowed under the federal rules.”

CBS News usefully chimed in:

The EPA said in a statement that all vehicle types are at record low carbon dioxide emissions, but “the market shift away from cars and toward sport utility vehicles and pickups has offset some of the fleetwide benefits.” (emphasis added)

In the 2021 model year, cars and station wagons, the most efficient vehicles, fell to 26% of U.S. new vehicle production, well below the 50% market share as recently as 2013, the EPA said. SUVs were a record 45% of new vehicle sales for the 2021 model year, while pickup trucks hit 16%.

2012 press release copied from National Archives. Poignantly, it promised that the nearly doubled auto efficiency would bring consumer savings as large as $1 per gallon cheaper gasoline.

Let that sink in: in just eight years, the U.S. market share of new sedans and station wagons fell practically in half, to 26 percent from 50 percent. (And no, CBS, that shift didn’t just offset some of the mpg benefits, it offset all of them, though credit the network for covering the story at all.)

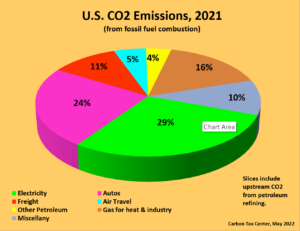

The Hill did well, with EPA report: Vehicle fuel efficiency flat in 2021. Otherwise, there wasn’t much coverage. Sure, Christmas was coming, and there were year-end stories to report. Still, it’s striking that such a big failure in a sector that now produces nearly a quarter of U.S. carbon emissions merited so little attention. (See our CO2 pie chart, further below.)

The silence of the greens

Robustly rising automotive fuel economy was, for decades, a cornerstone of mainstream environmental advocacy. So-called CAFE standards (the acronym denotes Corporate Average Fuel Economy) would, before long, turn most of America’s 200 million passenger vehicles into fuel-sippers, relieving pressure to drill in the Alaska National Wildlife Refuge and other sacrosanct natural areas, enabling some oil refineries to close, and cutting air and carbon emissions. Just make sure EPA kept ratcheting up the mpg standards, and all would be well.

Things turned out differently, of course. Not only did U.S. miles driven resume rising after a relative caesura from the mid-aughts to the mid-teens, but the fleet mpg average barely budged, due to “the market shift away from cars and toward SUV’s and pickups” noted by CBS News. Compounding the shift, long-standing CAFE loopholes grant bigger vehicles looser mileage targets.

Autos now (2021) account for 24% of U.S. CO2. Note that other transportation emissions (trucks, planes) are recorded separately.

Most of the big U.S. green groups just watched the shift unfold, essentially throwing in the towel. Either they didn’t grasp its extent or they viewed it as unstoppable. Maybe they felt constrained by their members’ and donors’ preference for the roomier and supposedly outdoors-friendly sport utilities. Who knows? But they basically gave up on improving actual vehicle fuel-economy, and the impact has been stark.

Even as the U.S. electricity sector has seen a substantial decline in carbon emissions, an estimated 36 percent drop from 2005 to 2021, the drop for automobiles has been only one-seventh as much — a measly 5 percent. The vastly improved mpg performance that was going to swamp growth in driving simply didn’t materialize.

What did eventuate from the big bulk-up of U.S. passenger vehicles has been a far greater menace to pedestrians, cyclists and users of smaller vehicles. Due to their greater mass and taller profile, those super-sized sport ute’s and pickups are tougher to maneuver and control, are harder to see around, are often driven with a greater sense of entitlement, and cause more damage when they hit someone.

Automotive researcher-journalist David Zipper tied things up recently for Bloomberg News, in a post trenchantly titled, “US Traffic Safety Is Getting Worse, While Other Countries Improve,”:

Uniquely, the US has seen larger SUVs and pickup trucks dominate its domestic car market. While the profitability of this trend has delighted automakers, the weight and height of these vehicles places other road users in greater danger. Research has linked the ascent of SUVs to the surge in US pedestrian deaths.

Possible futures for U.S. passenger vehicles

In his Bloomberg post, Zipper also noted that in other countries, “higher gasoline taxes (as well as weight-based fees adopted by countries like France) have slowed adoption” of large vehicles. (Doubtless there’s also a reinforcing cultural factor, or “path dependence,” that frowns on supersized vehicles and demurs from designing infrastructure around them, which discourages their use and thus helps keep the higher taxes on bigger vehicles politically defensible.)

Higher gasoline taxes are a form of carbon tax, of course. Indeed, resistance to increasing taxes on gasoline has always been a central sticking point to enacting carbon taxes — ironically so, given that those who cry the loudest tend to be big-car owners whose choice of vehicle effectively has them taxing themselves by locking them into purchasing more gallons.

Nevertheless, another locus of opposition to taxing gasoline to reduce its use has been — surprise! — the same green groups that habitually put all their chips on CAFE standards and other regulatory mechanisms. Sometimes these groups have even badmouthed the idea that gasoline use is somewhat price-elastic, mistaking short-term inflexibility for long-term (a confusion I pointed to in my 2015 post, What an Energy-Efficiency Hero Gets Wrong about Carbon Taxes — scroll down to “Argument #3”).

The supposed impossibility of reducing the use of gasoline by raising its price has been part and parcel of Big Green’s attachment to mpg standards — despite the fact that mileage reg’s do nothing to reduce driving and its vast negative consequences: not just traffic congestion but also poor health (sedentary living, car crashes, noise) and general unaffordability (car loan costs, upkeep expenses, costlier housing due to cars’ consuming urban and suburban land).

The supposed impossibility of reducing the use of gasoline by raising its price has been part and parcel of Big Green’s attachment to mpg standards — despite the fact that mileage reg’s do nothing to reduce driving and its vast negative consequences: not just traffic congestion but also poor health (sedentary living, car crashes, noise) and general unaffordability (car loan costs, upkeep expenses, costlier housing due to cars’ consuming urban and suburban land).

This does not bode well for enacting weight or weight-distance charges on the increasingly electric fleet of U.S. passenger vehicles. Yet weight-based fees might be our best bet for reining in the size and weight of EV’s and, thus, serving four vital societal objectives: (i) ensuring that shortages of lithium or other minerals critical to electric-vehicle batteries don’t hold back electrification of transportation; (ii) curbing the amount of electricity that must be generated to drive the EV fleet; (iii) easing the stresses that larger vehicles impose on urban and suburban form; and (iv) reducing traffic carnage, especially to pedestrians, cyclists and users of small vehicles.

With the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, which we at Carbon Tax Center strongly supported from the git-go (our extensive, ongoing write-up of the IRA is here), the Biden Administration has put in place an array of mutually reinforcing, intelligently crafted subsidies and incentives to electrify U.S. passenger travel. Climate and transportation advocates alike should now work to craft and enact incentives to steer vehicle electrification toward smaller, lighter, less-dangerous and city-friendlier forms of individual and family transportation. The choice between carbon taxes or weight-based charges or hybrids of the two is less important than getting strong incentives in place widely and soon.

They had to move quickly before military police, tasked with securing the airport, saw what was happening. The rebels targeted 13 private jets parked or preparing for takeoff, at least two belonging to NetJets, the Berkshire Hathaway subsidiary that bills itself as the world’s largest jet company and sells fractional ownership shares in private business jets.

They had to move quickly before military police, tasked with securing the airport, saw what was happening. The rebels targeted 13 private jets parked or preparing for takeoff, at least two belonging to NetJets, the Berkshire Hathaway subsidiary that bills itself as the world’s largest jet company and sells fractional ownership shares in private business jets. The justification is unarguable. Large personal fortunes feed carbon consumption and make a mockery of programs to curb it. As well, the surplus wealth of the superrich is probably the lone source of capital that can finance the worldwide uptake of greener energy and also pay for adaptation where it’s most critical.

The justification is unarguable. Large personal fortunes feed carbon consumption and make a mockery of programs to curb it. As well, the surplus wealth of the superrich is probably the lone source of capital that can finance the worldwide uptake of greener energy and also pay for adaptation where it’s most critical. “What the Schiphol people needed to do is destroy the airplanes on the tarmac and then destroy the airplane manufacturers,” said an ecosaboteur named Stephen McRae, an acquaintance of one of the authors, who recently completed a six-year prison sentence for industrial sabotage. Although he no longer participates in such criminal acts of destruction, he has a point. The planes grounded on November 5 are already back in the air. That doesn’t diminish the value of what the Schiphol rebels did, however. Actions that disrupt carbon comfort without violence or hardship are morale-building, the material from which more actions and eventually mass movements are made.

“What the Schiphol people needed to do is destroy the airplanes on the tarmac and then destroy the airplane manufacturers,” said an ecosaboteur named Stephen McRae, an acquaintance of one of the authors, who recently completed a six-year prison sentence for industrial sabotage. Although he no longer participates in such criminal acts of destruction, he has a point. The planes grounded on November 5 are already back in the air. That doesn’t diminish the value of what the Schiphol rebels did, however. Actions that disrupt carbon comfort without violence or hardship are morale-building, the material from which more actions and eventually mass movements are made.

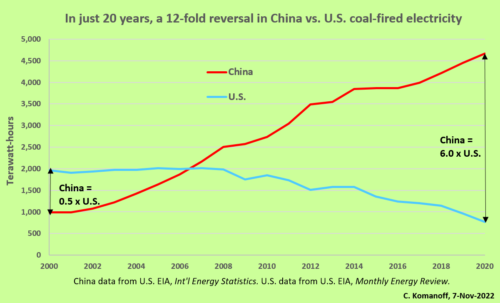

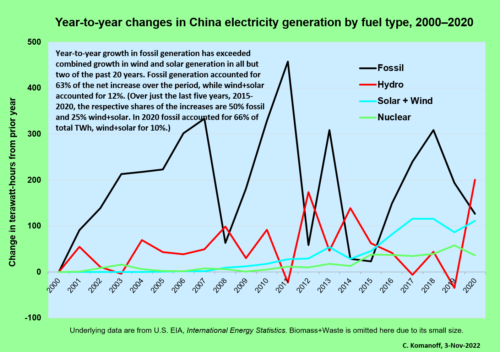

Those two years coincided with a flowering of climate optimism, with the U.S. and China reaching a bilateral agreement to curb emissions — ostensibly dissolving the “alliance of denial” by which both countries used each other’s inaction as a pretext to forego action on climate — and setting the stage for the 2015 Paris climate accord. Beginning in 2016, however, China’s fossil-fuel electricity generation (again, overwhelmingly coal-fired) recovered most of its prior increase pace. Year-to-year growth in fossil output has averaged 200 annual terawatt-hours since then.

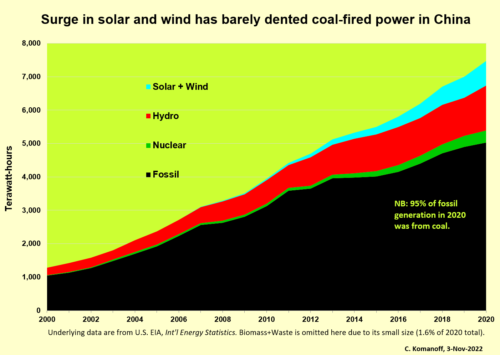

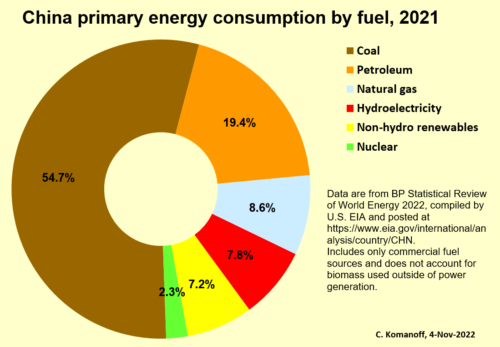

Those two years coincided with a flowering of climate optimism, with the U.S. and China reaching a bilateral agreement to curb emissions — ostensibly dissolving the “alliance of denial” by which both countries used each other’s inaction as a pretext to forego action on climate — and setting the stage for the 2015 Paris climate accord. Beginning in 2016, however, China’s fossil-fuel electricity generation (again, overwhelmingly coal-fired) recovered most of its prior increase pace. Year-to-year growth in fossil output has averaged 200 annual terawatt-hours since then. But in China, no single energy application rivals the burning of coal to produce electricity. It accounts for around one-third of the country’s primary energy consumption — a figure we computed by multiplying coal’s 55 percent share of 2021 China primary energy (see donut chart) and electricity’s estimated 60 percent share of the country’s total coal consumption (per the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s

But in China, no single energy application rivals the burning of coal to produce electricity. It accounts for around one-third of the country’s primary energy consumption — a figure we computed by multiplying coal’s 55 percent share of 2021 China primary energy (see donut chart) and electricity’s estimated 60 percent share of the country’s total coal consumption (per the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s

The Inflation Reduction Act likewise marks a turning point, at least for the time being, on long-running, world-damaging U.S. climate helplessness. True,

The Inflation Reduction Act likewise marks a turning point, at least for the time being, on long-running, world-damaging U.S. climate helplessness. True,