Justice Elena Kagan, commenting on the 6-to-3 Supreme Court decision in West Virginia v. EPA, quoted in Supreme Court Limits E.P.A.’s Ability to Restrict Power Plant Emissions, by Adam Liptak, in The New York Times, June 30.

SCOTUS Ruling: Bad for Climate, Good for Carbon Pricing?

Note: This post was amended on July 6 to include @bobinglis’s June 30 tweet, shown below.

Maybe we’re grasping at straws. But we see a possible silver lining in this week’s grievous Supreme Court ruling striking down US EPA’s authority to regulate carbon emissions via the Clean Air Act.

The gleam of hope is not that the decision didn’t dismember the federal government’s entire “administrative state” apparatus — you know, the tapestry of rules, regulations and procedures designed to further societal health, safety and accountability. We fear investigative journalist Amy Westervelt may be right that the ruling is a harbinger of steps in that very direction.

What I’m not seeing a lot of people get is that the West Va v EPA verdict is a harbinger. It’s the first step not the death blow. Overstating it obscures that, leaving people thinking it’s all over and ill-prepared for what comes next.

— Amy Westervelt (@amywestervelt) July 1, 2022

Rather, our thin beam of optimism is the opening the ruling could provide for carbon tax proponents to persuade our fellow climate advocates to lean less on fraught, slow and even quixotic approaches for tackling climate change, and to instead turn increasingly toward carbon taxing as a more-holistic and bulletproof way to bring down stubbornly high carbon emissions, both in the U.S. and worldwide.

In recent years, this space has done battle with what we’ve regarded as inadequate or even illusory climate strategies.

* We’ve criticized the decade-long campaign to divest financial and social institutions from fossil fuels, arguing in our posts and on our evergreen pages that capital will easily find ways to finance whatever legal product consumers demand, especially a product so economically and psychologically fraught as gasoline.

* We’ve hit back at the IMF’s unfortunate labelling of fossil fuels’ vast externality costs — both climate damage and immediate human-health harms — as “subsidies,” for fostering the fantasy that citizens need only stop their governments from bestowing public tax dollars on fossil fuel companies, and Big Carbon will crumble and wither away.

* We’ve even questioned the keep-it-in-the-ground movement, arguing, heretically, that “Oil that doesn’t flow to refineries through the Dakota Access Pipeline [to take one example] will instead come from somewhere else – Kuwait or Texas or a hundred other places – to be burned in cars, trucks and planes.” Our movement’s focus, we’ve argued, must be demand, not supply.

* And we’ve looked long and hard at the climate value of environmental regulation — the very approach the Supreme Court threw under the bus yesterday. Look at how, a year ago, we contrasted the fabulous success of the 1970 Clean Air Act and its 1977 and 1990 amendments in slashing concentrations of particulates and other harmful pollutants in “ambient air,” with the less-technology-amenable issue of carbon emissions:

These and similar successes have led many climate advocates to urge similar regulatory pathways to curb carbon emissions. [Yet] regulatory approaches may offer only modest prospects for controlling and reducing emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, for several reasons. For one thing, the absence of antipollution devices for capturing or lowering CO2 emissions limits the scope of technology-forcing regulation. For another, promulgation of regulations is necessarily piecemeal and reactive. Moreover, the regulation-setting and administering process itself is cumbersome, delay-prone and subject to legal challenge by carbon interests.

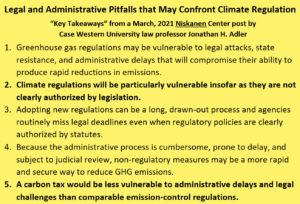

From Niskanen Center post. Link is in text. We’ve added emphasis to #2 and #5.

We backed up that argument with reasoning from a penetrating paper by Case Western University law professor Jonathan Adler. The sidebar at right has Prof. Adler’s own “key takeaways” from the summary version he published on the Niskanen Center’s website. We highlighted two: A, climate regulations that aren’t clearly authorized by legislation will be particularly vulnerable to legal challenges — as we saw this week, when the six right-wing justices took advantage of the absence of explicit mentions of climate or carbon in the Clean Air Act and its amendments. And B, compared to emission-control regulations, a Congressionally enacted carbon tax should be less vulnerable to such challenges.

This isn’t to say that a carbon tax is just around the corner. We readily admit that a path to enacting a meaningful federal carbon tax — not a token, Exxon-style levy that damages coal but not oil or gas, but a robust carbon price that can reach triple digits in a half-dozen or fewer years — is almost impossible to discern.

Rather, now that essentially all of the prominent alternatives have been eviscerated or emasculated, it’s time for climate advocates to rethink, and, hopefully, relinquish, their anti-carbon-pricing positions.

The Carbon Tax Center has strived to be a climate team-player. At least since the start of the Trump administration, we’ve acknowledged the near-impossibility of passing a federal carbon tax in the current political configuration, and have instead pulled for less-ambitious but more-achievable (or so they seemed) incremental steps.

Just last fall, we wrote that “There’s logic in refraining from the one overarching policy that could lead the way to the deep cuts Biden is seeking: an economy-wide carbon tax. Giving businesses and households money to go green [instead] is more palatable, though less potent, than charging them for burning carbon.”

But we’ve also strived to be truth-tellers. That’s why we called that 2021 post, “Without a Carbon Tax, Don’t Count on a 50% Emissions Cut.” And it’s why we’re a little less inclined than some of our climate comrades to go into full mourning over yesterday’s Supreme Court decision .

Supreme Court leaves it up to Congress to act on climate change. That’s OK because Congress can enact a carbon tax and a carbon border adjustment that can make the solution go worldwide. Tax pollution. Un-tax income. Conservatives in Congress, here’s your chance! We need you!

— Former Rep. Bob Inglis (@bobinglis) (R-SC) June 30, 2022

Please also note that unlike the indefatigable Bob Inglis, who bravely fought for carbon pricing as a six-term Member of Congress (1993-1999, 2005-2011) from South Carolina’s 4th District, we’re not calling on “Conservatives in Congress” to push for carbon taxing. We would love it if even a few did, but that ship sailed over a decade ago, as we’ve summarized on CTC’s Conservatives page.

To sum up: Yes, the Supreme Court ruling was ignorant. Yes, it was destructive. Yes, it’s almost certainly a harbinger of worse. But it didn’t demolish policies that were on course to rescue our planet and make Biden a climate hero.

Yesterday’s decision did damage, but maybe it pulled some wool from our eyes as well.

Already, the link between greenhouse-gas emissions and sweltering temperatures is so clear that some researchers say there may soon no longer be any point trying to determine whether today’s most extreme heat waves could have happened two centuries ago, before humans started warming the planet. None of them could have.”

Raymond Zhong, How Extreme Heat Kills, Sickens, Strains and Ages Us, New York Times, June 13.

Global warming has made the severe heat wave that has smothered much of Pakistan and India this spring hotter and much more likely to occur, climate scientists with World Weather Attribution, a collaborative effort among scientists to examine extreme weather events for the influence, or lack thereof, of climate change, said Monday. They said that the chances of such a heat wave increased by at least 30 times since the 19th century, before widespread emissions of planet-warming gases began. The relentless heat, with temperatures soaring beyond 100 degrees Fahrenheit for days, particularly in Northwestern India and Southeastern Pakistan, has killed at least 90 people, led to flooding from glacial melting in the Himalayas, contributed to power shortages and stunted India’s wheat crop, helping to fuel an emerging global food crisis. The study found that a heat wave like this one now has about a 1 in 100 chance of occurring in any given year. Before warming began, the chances would have been at least about 1 in 3,000. And the chances would increase to as much as 1 in 5, the researchers said, if the world reaches 2 degrees Celsius of warming, as it is on track to do unless nations sharply reduce emissions.”

New York Times climate reporter Henry Fountain, in Climate Change Fuels Heat Wave in India and Pakistan, Scientists Find, May 23.

Bitcoin Mining is Gobbling Up New York’s Precious Renewable Energy

(As published today in NYC-based Gotham Gazette. Footnotes appear at end. — C.K., May 13, 2022)

Like time in Steve Miller’s classic-rock song, New York’s decarbonization targets keep slipping into the future.

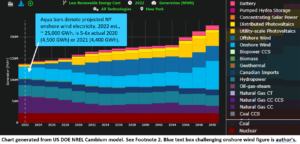

Highway widenings are spurring more driving. Suburban resistance to upzoning is locking in energy-demanding sprawl. Electricity from the state’s wind turbines shrank last year,1 even as climate advocates, relying on dodgy U.S. Energy Department modeling, overstate future carbon reductions from “electrifying everything.”2

Promising developments like offshore wind leasing and new transmission to carry hydroelectricity from Quebec barely compensate, if at all, for carbon emissions unleashed by closing the Indian Point nuclear plant. As I have pointed out elsewhere, shutting existing zero-carbon power sources means that new ones don’t actually cut emissions; at best, they keep us running in place, punching huge holes in pledges to achieve a carbon-free power grid by 2040.

Promising developments like offshore wind leasing and new transmission to carry hydroelectricity from Quebec barely compensate, if at all, for carbon emissions unleashed by closing the Indian Point nuclear plant. As I have pointed out elsewhere, shutting existing zero-carbon power sources means that new ones don’t actually cut emissions; at best, they keep us running in place, punching huge holes in pledges to achieve a carbon-free power grid by 2040.

To this dreary picture, add crypto mining — enormous networks of electron-eating computers running 24-7 so that digital currencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum can maintain virtual “coins” or “tokens” in encrypted ledgers that bypass traditional third parties like banks.

From Buffalo and the Finger Lakes to the state’s northern tier, crypto entrepreneurs are building new generators or firing up retired ones to power their crypto mining operations. Other crypto sites draw on the grid.

Self-sourced or not, the requisite electricity ends up forcing additional burning of fossil fuels, as Sierra Club researchers documented in extensive comments this week to the President’s Office of Science and Technology Policy, pushing the state’s ambitious decarbonization goals further out of reach. To what end?

In Uber’s Footsteps

Enigmatic, opaque, futuristic — crypto-currency cries out for historical analogues. Here’s one: Uber.

Uber burst on the scene in the early 2010s not as a new form of transportation but a new kind of network enabling a reconfiguration of transportation. Its appeal was tailored around three promises: it would enhance traffic efficiency by eliminating cruising for fares; it would extend convenient for-hire vehicle service outside Manhattan; and it would end service refusals to people of color.

The packaging — sleek and app-enabled — augured a frictionless, digital future. With a few taps New Yorkers could summon a chariot.

The results were mixed. We now know that stockpiling of Ubers in Manhattan has wrought even more gridlock than taxi cruising. But Uber did broaden access to for-hire vehicles, even as it bled ridership from the MTA and, worse, rained economic ruin on the incumbent yellow-cab industry.

Bitcoin and other crypto-currencies come with their own glossy promises, though these are more chameleon-like. (Earlier this year New York Times columnist Paul Krugman disparaged them as “word salad.”) Among them, as Annie McDonough reported recently in City & State, is the prospect of liberation from ingrained discriminatory banking and lending by U.S. financial institutions.

“[Crypto backers] see the technology as an economic equalizer,” writes McDonough. “A tool not just for the rich to get richer, but for people who have been discriminated against by banking institutions or locked out of investment opportunities, including people of color and low-income communities.”

Really? In New York, and almost certainly anywhere else, unbanked households overwhelmingly lack the requisite credit history or liquid assets — bank accounts, debit cards, credit cards — to purchase cryptocurrency tokens. Moreover, scammers and grifters are finding crypto fertile territory for high-tech swindles, as New York Times columnist Farhad Manjoo noted this month. An arguably safer and more effective way to root out credit segregation would be to speed Biden administration rulemaking to add teeth to the Community Reinvestment Act — the 1977 law intended to repair decades of redlining.

The emergence of crypto-front groups like the National Policy Network of Women of Color in Blockchain demonstrates the industry’s readiness to exploit deep-seated bitterness over legacy redlining. So does the participation in crypto lobbying of Bradley Tusk, the one-time Mike Bloomberg consigliere who a decade ago deftly deployed Black fury over persistent taxi discrimination to help Uber eradicate cabbies’ exclusive right to pick up street hails in Manhattan and subsequently helped fend off serious regulation of the app-ride industry for several crucial years.

Let’s Burn Up The Grid

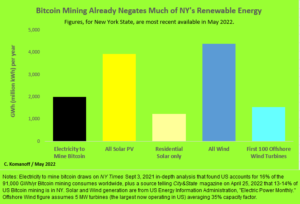

There is no registry of electricity consumed by crypto mining in New York State. Worldwide, though, crypto burns through an estimated 91,000 gigawatt-hours (or, 91 billion kilowatt-hours) of electricity annually, according to a New York Times survey of crypto last September. Some 16% of that, or 15,000 GWh, is said to be consumed in the United States.

While New Yorkers are accustomed to thinking of our state as resource-poor, crypto miners are now exploiting half-a-dozen hydro power sites and formerly boarded-up fossil-fuel plants in northern and western New York. One industry source cited by City & State estimates that 13-14% of his company’s U.S. crypto mining takes place in our state. Extrapolating that share across the industry, crypto is annually consuming 2,000 GWh of electricity in New York State — a figure that could grow not just with increased transactions but with ever-more complex digital encryption.

While New Yorkers are accustomed to thinking of our state as resource-poor, crypto miners are now exploiting half-a-dozen hydro power sites and formerly boarded-up fossil-fuel plants in northern and western New York. One industry source cited by City & State estimates that 13-14% of his company’s U.S. crypto mining takes place in our state. Extrapolating that share across the industry, crypto is annually consuming 2,000 GWh of electricity in New York State — a figure that could grow not just with increased transactions but with ever-more complex digital encryption.

Even holding at 2,000 GWh, that’s a lot of juice: more than the electricity generated last year from all the solar panels on residential buildings in the state, or more than what will come from the first 100 promised offshore wind turbines once that industry launches (see graph below). And, though crypto in New York consumes less electricity than all current solar or wind, that comparison is of no comfort, as those renewable sources need to be displacing fossil fuels (primarily fracked gas) from the state’s grid — which they can’t do if their output is effectively being consumed mining Bitcoin.

The operative word, “effectively,” encompasses two distinct but complementary dynamics. Grid dynamics dictate that any new locus of demand such as Bitcoin forces utilities to draw more heavily on fossil-fuel generators, because the non-carbon sources — nukes as well as renewables — already run as flat-out as they can. The climate dynamic is that from a statewide perspective, additional use of fossil-fuel generators negates the carbon-reduction benefits that wind and solar and nuclear would otherwise provide.

This perspective casts a harsh light on claims that a particular crypto installation is being renewably sourced. Connecting crypto to a refurbished hydro dam or solar or wind farm may sound green, but all those whirring hard drives are really siphoning off carbon-free electricity that now “won’t be available to power a home, a factory or an electric car,” as the Times’ 2021 story put it. (One hopes that the irony of crypto adherents miscounting green electrons doesn’t carry over to their currency bookkeeping.)

Carbon Tax vs. Crypto?

A stiff New York State carbon tax could slow and even reverse the rise of cryptocurrency here (likewise nationwide).

The rise in electricity prices would undermine whatever competitive advantage Bitcoin miners gain from locating in New York. Some miners would leave, new ones would stay away, and those who stay would endeavor to blunt the impact of the tax by upgrading their efficiency.

Not only that, crypto miners seeking zero-carbon generation increasingly would find themselves competing with non-crypto businesses seeking to contain their power costs. Other businesses, less power-intensive per dollar of revenue, would be in position to outbid the crypto companies.

The prospective flight to other jurisdictions could help build momentum to tax carbon emissions there as well, as more states and countries come to conclude that crypto jobs and revenues aren’t worth straining their grids, not to mention trashing their air-sheds and stealing their quiet.

This isn’t to hold out carbon taxing as a one-bullet crypto killer — we need many bullets for that, the bigger the better — but to illustrate its broad potential to stop frivolous (and in this case imbecilic) new uses of electricity before they can gain a foothold.

This isn’t to hold out carbon taxing as a one-bullet crypto killer — we need many bullets for that, the bigger the better — but to illustrate its broad potential to stop frivolous (and in this case imbecilic) new uses of electricity before they can gain a foothold.

Why not regulate crypto away? That battle would consume years, tying down policy resources while emissions continued to spew. Worse, we have neither the time nor the ability to see around corners required to enact, piecemeal, restraints on each new locus of energy demand.

Even as energy-efficiencies continue to do wonders — total U.S. electricity use last year was just a few percent higher than in 20053 — underpriced electricity elicits new hellspawns of needless use that undo much of that progress.

Carbon taxes by themselves can’t solve everything that ails climate. But they could, for a change, get the solutions out in front of the problems.

***

Charles Komanoff, long-time New York policy analyst and environmental activist, directs the Carbon Tax Center. On Twitter @Komanoff.

1US Energy Information Administration, “Electric Power Monthly,” Table 1.14.B, “Utility Scale Facility Net Generation from Wind,” shows 4,522 GWh in New York State in 2020 and 4,387 GWh in 2021.

2To estimate future carbon reductions from the December 2021 New York City ban on gas heating and cooking in new buildings, the law’s proponents and the Dec. 15, 2021 New York Times story reporting on it both cited a Dec. 10, 2021 post, Stopping Gas Hookups in New Construction in NYC Would Cut Carbon and Costs, by the consultancy RMI. The RMI authors note that their calculations employed future electricity grid emission factors modeled by U.S. DOE’s National Renewable Energy Lab’s “Cambium” dataset. Examination of that dataset reveals, inter alia, that it assumes a non-existent five-fold increase in New York State on-shore wind-generated electricity from 2020 to 2022.

3Figures from US Energy Information Administration, “Electric Power Monthly,” Table 7.2a Electricity Net Generation: Total (All Sectors)” supplemented by Table 10.6 (“Electricity Net Generation from Distributed Solar”) indicate total U.S. electricity generation of 4,164,565 GWh in 2022 and 4,055,785 GWh in 2005. For those interested, the implied compound annual average growth rate over those 17 years is a minuscule 0.17 percent.

Correction: This post was amended on May 26 to reflect the fact that New York’s estimated 13-14% share of U.S. crypto mining applies to a single crypto company rather than industry-wide. The extrapolation to other companies is the author’s, not the source’s.

May 16 addendum: We strongly recommend How crypto made me fall in love with carbon pricing all over again, an April 27 essay by Frontier Group energy analyst Tony Dutzik covering the intersection of crypto mining, carbon pricing, energy demand and Jevons Paradox.

The Climate Movement In Its Own Way

The Nation magazine today published my essay, The Climate Movement In Its Own Way. I’ve cross-posted it here to allow comments and offer context.

Use link at top to access the original version of this post in The Nation.

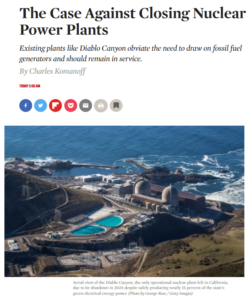

It’s a follow-on to my April 4 essay, also in The Nation, The Case Against Closing Nuclear Power Plants, which I posted here under the title, For Climate’s Sake, Don’t Shut U.S. Nukes.

The new piece calls on progressives in the climate movement — a bulwark of the magazine’s readership — to move beyond ideology and make the climate movement more pragmatic and holistic by supporting carbon pricing.

In introducing my April 4 post, I wrote:

[This post] implicitly embodies a hope that my willingness to examine my own deeply-held convictions in a new light may encourage others to do likewise with their own climate dogma. Reconsideration of ideologically-based objections to carbon pricing by self-proclaimed progressives would be a good place to start.

Consider today’s post an explicit expression of that hope.

— C.K., April 30, 2022

PS: The new post had to be shoehorned into a tight word count. The version below restores a half-dozen phrases cut from the version in The Nation.

The Climate Movement In Its Own Way

After decades of critically documenting nuclear power’s outsize costs, I finally admitted to myself that the carbon benefits from continuing to run US nuke plants are substantial, and in some respects irreplaceable. I made the case for keeping them open in an April article on TheNation.com.

Closing New York’s Indian Point reactors last year was a climate blunder, I wrote. Not just because fracked gas is now filling the breach, but because the need to replace the lost carbon-free power means that new wind and solar farms won’t drive emissions down further. California, facing the same equation, should shelve its plan to shutter the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant in 2024, I said.

“Total bullshit,” a lifelong anti-nuker wrote me. “You should be ashamed.” More representative of the comments, though, was this: “Continued reliance on nuclear power going forward now is part of the price of our collective past failures.”

Amen. The failures propping up US carbon emissions are multiple. Not just Senator Joe Manchin, who torpedoed President Biden’s Build Back Better clean-energy legislation. Not just the Senate Republicans, any one of whom could have cast the critical 50th vote. And not just Big Carbon, whose dark money and disinformation perpetuate climate inaction.

Amen. The failures propping up US carbon emissions are multiple. Not just Senator Joe Manchin, who torpedoed President Biden’s Build Back Better clean-energy legislation. Not just the Senate Republicans, any one of whom could have cast the critical 50th vote. And not just Big Carbon, whose dark money and disinformation perpetuate climate inaction.

Through its own poor choices, the climate movement is failing as well.

Too many of our climate campaigns are ill-considered. Too much of our legislative agenda is narrow-gauged. Too often, our lens for assessing climate proposals is ideological rather than pragmatic.

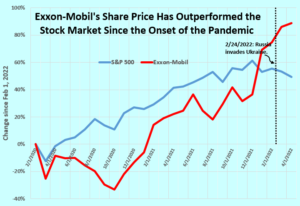

Consider the decade-long campaign to induce pension funds and banks to divest their fossil-fuel holdings. Exxon-Mobil’s share price wobbled for years, but since early 2020 Exxon’s stock has risen faster than the market average. Is Big Oil shamed and starved for new capital today? Not with roaring demand for oil and gas. US motorists’ insanely over-powered, super-sized vehicles account for about a tenth of worldwide petroleum consumption. Yet challenges to American motordom come mostly from outgunned cycling and transit campaigners, not the climate movement.

Now, with most federal action blocked, climate activists sought and won a ban on gas heat in new buildings in New York City, though they failed in their first push for a statewide ban.

The drive to “electrify everything” is laudable, given that electricity can be decarbonized whereas gas furnaces and stoves cannot. Yet trying to take the ban statewide elbowed aside bolder ideas, such as legalizing accessory dwelling units and stopping highway widenings.

To be sure, not everyone is ready to admit that fatter highways and pastoral, exclusive suburbs are carbon disasters. But only broader campaigns can link climate to other pressing concerns like homelessness, housing unaffordability, costly gasoline, and traffic violence.

The granddaddy of US climate failures, of course, is the absence of the one policy that economists believe could unlock the vast emissions reductions needed to meet the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius: national carbon taxation.

A robust federal carbon tax isn’t just the sharpest card in the climate policy deck. It’s like adding a whole new deck to the one we already have.

A straightforward “price on carbon” — administered not via easily gamed cap-and-trade schemes but through “upstream” levies on the carbon content of fuels — was once thought appealing to left and right alike. It is now abjured by both.

The right, of course, is both repellently all-in on fossil fuels and hyper-aware that its wealthy base of profligate carbon consumers would pay the most through a carbon tax. Which makes the left’s antipathy to carbon taxes not just surprising but downright bizarre.

This hesitation has multiple strands: seeing carbon pricing as another contrivance of the predatory capitalism that built white wealth off the land and labor of Indigenous and African-descended peoples; suspicion that carbon pricing lets polluters avoid reducing local emissions by purchasing “offsets”; a misplaced conviction that carbon pricing in California has worsened disproportionate pollution burdens on disadvantaged communities; and excessive faith that a regulatory approach can untangle the multiple strands that enforce fossil-fuel dependence.

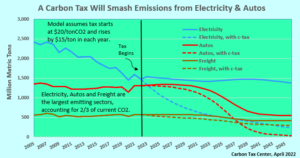

Economic models abound to show how fast carbon taxes will shrink the use of fossil fuels. Models aren’t life, but they agree broadly that a robustly rising federal tax could, within a decade, dial back US emissions by about a third.

To turn our backs on carbon reductions on that scale is, I believe, suicidal.

Our worsening climate stalemate led me to abandon my silence as existing nuclear power plants were extinguished. A similar rethink on carbon taxes by progressives won’t win over climate denialists. In time, though, with a more far-sighted left ascendant, it could become a stepping stone to climate progress.

Charles Komanoff, a longtime environmental activist and expert on nuclear power economics, directs the Carbon Tax Center.

Exxon doesn’t care if you divest. Neither does climate.

The campaign to combat climate change by inducing pension funds, universities and other prominent fiduciaries to dump their fossil-fuel holdings has failed. Ten years into the divestment project, it’s time to move on.

Divestment campaigning doesn’t seem to have damaged Exxon’s share price since 2020.

When the writer and climate activist Bill McKibben kicked off the campaign in a July 2012 Rolling Stone article, Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math, the rationale was three-fold: (1) dry up capital and make it harder for the fossil fuel industry to create new mines, wells, pipelines and terminals; (2) weaken the industry’s social and political standing so it couldn’t easily block pro-climate policy; and (3) by hanging a “Dump Me” sign around Big Oil, amp up climate organizing. Not for nothing did McKibben subtitle his Rolling Stone article, “Make clear who the real enemy is.” It was Exxon and its brethren.

How’s it going, ten years on? Not well. The clearest indication is Exxon-Mobil stock’s new-found attractiveness to investors. From Feb. 1, 2020 to Feb. 1, 2022, a two-year period that predates Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and brackets the Covid-19 pandemic, Exxon’s stock price climbed 75 percent, outpacing the 55 percent rise in the S&P 500 index.

While non-U.S. oil giants Saudi Aramco and BP have appreciated less than the S&P benchmark, the #2 and #3 U.S. oil companies, Marathon Oil and Valero Energy, have matched Exxon’s faster-than-average share price rise. Unsurprisingly, Exxon’s market-beating performance accelerated since Feb. 1, as the oil industry reaps the fruit of high prices without yet suffering much contraction in demand.

It is true that Exxon and other oil majors under-performed the market from 2012 to 2020. So why are oil stocks now so buoyant? The answer lies in robust demand for petroleum products, both in the U.S. (about a fifth of world usage, with half of that in motor fuels) and globally. Until Russia attacked Ukraine, disrupting trade and dampening near-term economic expectations, world petroleum consumption this year was headed to near-record levels.

Is it, though?

More importantly, considering that stock prices essentially embody investors’ expectations of future earnings streams, the lords of capital are betting on the oil and gas business to stay profitable for some time.

Reserves will not stay in the ground, in other words, unless and until consumption shrinks. It ought to be obvious that oil consumption drives production, not the other way around. The same “whack-a-mole” syndrome that made “keep it in the ground” campaigns ineffectual from a climate standpoint (as I lamented in this 2016 post) also afflicts efforts by socially responsible investors to starve capital flows to fossil fuel corporations.

No matter how far divestment penetrates bank boardrooms or Ivy League endowments, a world intent on using fossil fuels can always count on a vast array of wealth holders to finance their resupply.

McKibben admitted as much last fall, shortly after the New York Times reported on meticulous research by the Private Equity Stakeholder Project that found that private equity funds for a decade had been investing $100 billion a year in fossil fuel energy. In an October 2021 Times op-ed (see headline above), he admitted the real purpose of divestment campaigns: to build the climate movement and erode the social and political standing of the fossil fuel industry (what I earlier called aims #2 and #3):

Since most people don’t have oil wells or coal mines in their backyards, divestment is a way to let a lot of people in on the climate fight, because they have a link to a pension fund, mutual fund, endowment or other pot of money. When we began the divestment campaign, our immediate goal was, as we put it, to “take away the social license” of Big Oil. (emphasis added)

This Oct 13, 2021 NY Times story demolished a key rationale for fossil-fuel divestment campaigns.

Movement-building is vital. Eroding the social standing of fossil-fuel extractors and purveyors is overdue. But what happens when divestment activists discover that moving their college or municipal pension fund out of fossil fuels hasn’t visibly changed the material world of energy production and consumption?

In the 2021 op-ed, McKibben added that divestment campaigning “was a vehicle to let people know the essential truth about the fossil fuel industry, which is that its oil, gas and coal reserves held five times as much carbon as scientists said we could safely burn.” That 5-fold incongruity, in fact, was the titular “new math” in his archetypal 2012 Rolling Stone article.

The math is unassailable. McKibben’s new metric demonstrated, ingeniously and incontrovertibly, the incompatibility between oil industry health and planetary health. Yet divestment, as a tactic, hasn’t delivered.

Divestment campaigners have a world of actions and organizing to do instead. For the next six months, though, they need to focus on political action. Electoral action.

Odds be damned, the Democrats have got to hold onto Congress this November. Political commentator Jamelle Bouie reminded us why recently when he was asked why “the Democrats can’t seem to get traction on [climate and other progressive policies] that enjoy broad support”:

In terms of getting policies through Congress, they just don’t have the votes. [But] I think this picture would look very different if there was one more or two more [Democratic] senators. If Cal Cunningham in North Carolina had won [in 2020], if Susan Collins’s opponent in Maine [Susan Gideon] had won, we’d be looking at a very different situation.

Needless to say, a very different situation, of the opposite sort, is what we’ll be looking at if the other, climate-denying, democracy-wrecking party prevails in the midterms. Between now and Tuesday, Nov. 8, not just divestment but probably all climate-focused organizing needs to yield to, or at least be subsumed by, electoral campaigning.

If your state or district is competitive, start electoral organizing now. If not, these resources can plug you in:

- People’s Action has both electoral and non-electoral volunteering.

- Swing Left has local chapters to connect you for phone-calling, post-carding, donating, etc.

- For down-ballot electioneering (which also brings people to vote for up-ballot races): Sister District.

- For Spanish-speaking calling in AZ, connect to Mision por Arizona via Mission for Arizona.

- To donate $$ to grassroots rather than party organizations: Movement Voter Project.

A Pause in Globalization Could Reset Carbon Emissions — and U.S. Politics

Last weekend I bicycled to Long Beach, the Long Island town where I grew up. From the boardwalk, squinting into the sun, my riding partner Dave and I could make out a dozen freighters strung in a long line in the Atlantic Ocean, stacked up like aircraft waiting to land.

Giant ships offshore weren’t something you saw often from Long Beach in the last century. A solitary ordinary freighter was noteworthy. The dozen big ships last Saturday doubtless were a symptom of some downstream jam-up in the supply chain. But they were also a telltale of the vast expansion of global trade since globalization took rise several decades ago and made Asian factories the prime U.S. source of consumer goods.

Yellow circles mark cargo ships we saw strung out in the Atlantic. Photo: David Clark.

As coincidence would have it, both Dave and I had read Paul Krugman’s day-before NY Times column, Putin May Kill the Global Economy. “There are good reasons to worry that we’re seeing an economic replay of 1914,” Krugman wrote, referring to “the year that ended what some economists call the first wave of globalization, a vast expansion of world trade made possible by railroads, steamships and telegraph cables.”

Krugman envisages Russia’s invasion of Ukraine triggering a replay of 1914. Not just the withdrawal from trade of Russian hydrocarbons and Ukrainian wheat but a “partial retreat from globalization,” i.e., a shrinkage in the “world-spanning supply chains” that now constitute global manufacture.

“What Putin has taught us is that countries run by strongmen who surround themselves with yes-men aren’t reliable business partners,” Krugman says, eyeing China above all. “So if you’re a business leader right now,” he writes, “surely you’re wondering whether it’s smart to stake your company’s future on the assumption that you’ll keep being able to buy what you need from authoritarian regimes. Bringing production back to nations that believe in the rule of law may raise your costs by a few percent, but the price may be worth it for the stability it buys.”

Who can disagree? What Krugman didn’t consider, though, is that the simplification and shortening of global supply chains as an antidote to irrational autocracy could become the political equivalent of carbon taxes on international shipping.

I’ve long harbored the notion that a sufficiently airtight regime of global carbon taxes might put a damper on world trade by making ocean-going shipping more expensive. Much trade would remain, of course, although the extent would depend on the magnitude of the tax. At the margin, though, the enormous movement of raw materials and goods across thousands of miles of ocean (or, more expensively, via air freight) would slow and perhaps even decline.

Krugman didn’t see deglobalization’s silver linings. We do.

The resulting cut in global carbon emissions would be no small thing. Global shipping accounts for 2.2 percent of greenhouse gas emissions worldwide, Time magazine reported recently, a figure that encompasses methane and other GHG’s and thus probably equates to 3 percent of worldwide CO2.

Deglobalization’s salutary effect on domestic manufacture might ripple even wider. Automation notwithstanding, relocating the making of goods for the U.S. market to the United States would raise factory employment and the number of stable, high-wage jobs. That in turn might restore a semblance of cohesiveness and meaning to the vast hollowed-out regions of middle America that since the Great Recession have turned in despair to opiates — pharmaceutical and political.

To be sure, this can sound very pie-in-the-sky, until you remember the pre-eminent role that dignified, well-paying manufacturing jobs played in U.S. progressive politics in the last century. Starting with Franklin Roosevelt and continuing until Reagan, labor and political organizing in America’s industrial unions played a vital part in furthering racial and economic equality through policies like progressive taxation and civil rights legislation, as historian Michael Kazin recounts in his latest book, What It Took to Win: A History of the Democratic Party.

It’s not a huge stretch to triangulate from Kazin’s history of mid-century democratic capitalism and Krugman’s prognosis of deglobalization to imagine a resurgence in the kind of working-class progressivism that has largely been missing from the push for a Green New Deal. The victory last week through nontraditional, grassroots organizing by the worker-led Amazon Labor Union in Staten Island, NY, points in this direction. Over time, rising labor power accompanying renascent domestic manufacturing could help deliver the electoral wins and legislative energies needed to help the U.S. transit from fossil fuels to green energy.

Of course this is my take, not Krugman’s. What worries him about deglobalization isn’t the prospect that “wealthy, advanced economies will end up slightly poorer” as cheap imports recede. It’s the possible brake on economic advancement in “nations like Bangladesh that have made progress in recent decades [due to] access to world markets.”

Curiously for a columnist who frequently invokes climate change, Krugman didn’t mention the other, more dire prospect facing Bangladeshis: that continued “progress” in the form of fossil-fueled growth will lead to massive destruction of their country as the sea overwhelms it, monsoons fail, crops collapse, and desperate migrations of biblical numbers ravage the inland. Unless some thing or combination of things creates a different future.

In his 2020 novel, The Ministry For The Future, the “speculative fiction” writer Kim Stanley Robinson conjured a distinctive deus ex machina: “crash day” — an anonymous worldwide action causing jetliners to fall from the sky, killing passengers and crews but bringing down the curtain on hydrocarbon-fueled, climate-damaging aviation (zero-carbon airships take their place) and catalyzing, finally, a rapid global turning from fossil fuels.

After a decade of pining for a global carbon tax to reverse American deindustrialization, constrain global shipping, and then some, Krugman’s forecast of an autocrat-driven but nonviolent trade slowdown can look mighty attractive.

Addendum, May 9: A May 4 NY Times story, The Era of Cheap and Plenty May Be Ending, about the new logistical fragility of global supply chains, noted: “More firms reported moving their supply chains out of China to other countries, and American executives were more positive about bringing more manufacturing to the United States.”

Continued reliance on nuclear power going forward now is part of the price of our collective past failures.”

Drew Keeling, commenting on CTC post, For Climate’s Sake, Don’t Shut U.S. Nukes.

For Climate’s Sake, Don’t Shut U.S. Nukes

The Nation magazine this morning published my essay, The Case Against Closing Nuclear Power Plants. I’ve cross-posted it here to allow comments and offer context.

Use link at top of text to access the original version of this post in The Nation.

The piece had its genesis in a more expository post I published in 2020 in the NYC-based Gotham Gazette, Drones With Hacksaws: Climate Consequences of Shutting Indian Point Can’t Be Brushed Aside. In that essay, I dismantled the assurances of reactor-shutdown advocates that bountiful infusions of efficient and renewable energy will take the place of the nuclear-powered Indian Point plant’s carbon-free electricity. The problem wasn’t simply the slow rate at which new green energy is being added, but that when green energy sources must replace a standing power source that itself replaces fossil fuels, their effective climate value is zero.

I believe my essay in The Nation is noteworthy on several grounds.

First, it adds the weight of my long experience questioning nuclear power’s economic viability to a Feb. 1 letter from climate pioneer Jim Hansen, Nobel laureate and former U.S. energy secretary Steve Chu, and 77 other distinguished personages to California Gov. Gavin Newsom that, in effect, urged the state to avoid duplicating, on the West Coast, the grievous error of shutting a similarly questionably-sited reactor complex (Indian Point) on the East.

Second, the essay advances a more systemic view of the climate consequences of extinguishing extant zero- or low-carbon energy facilities whose operation is already keeping fossil fuels in the ground and carbon emissions out of earth’s atmosphere.

Third, it implicitly embodies a hope that my willingness to examine my own deeply-held convictions in a new light may encourage others to do likewise with their own climate dogma. Reconsideration of ideologically-based objections to carbon pricing by self-proclaimed progressives would be a good place to start.

— C.K., April 4, 2022

The Case Against Closing Nuclear Power Plants

On a bright spring day in 1979, before thousands who were propelled to Washington, D.C., by the Three Mile Island reactor meltdown, I pronounced nuclear power’s rapid expansion disastrously unaffordable. My remarks drew on years of work chronicling reactors’ skyrocketing capital costs.

Forty-three years later, in February, in the wake of the failed Glasgow climate summit, I wrote to California Gov. Gavin Newsom, urging him to defer the planned shutdown of the state’s last nuclear plant. Closing Diablo Canyon, a Reagan-era complex near San Luis Obispo, would damage the state’s climate leadership as it strives toward zero-carbon energy, I argued.

I sent my letter just days before Vladimir Putin’s tanks rolled into Ukraine and thrust nuclear power back in the news, in typical ambiguity.

On one side are legitimate fears that Russia’s seizure of the giant Zaporizhzhia reactor complex in southern Ukraine, the largest in Europe, and the stricken Chernobyl plant in the north, near Belarus, could precipitate massive releases of radiation.

On the other is the stomach-churning awareness that Germany’s reactor closures over the past decade deepened its dependence on Russian gas, helping keep the Kremlin supplied with Western cash while slowing its own progress to climate-safe energy.

In America, meanwhile, the nearly one hundred nuclear plants that have ridden out the post-Three Mile Island cancellations and post-Fukushima shutdowns operate under the radar, their climate and pocketbook benefits taken for granted. It’s time we paid attention.

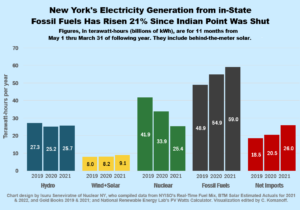

The climate crisis demands that NY’s electricity supply from fossil fuels shrink rapidly. Since Indian Point was closed, it has risen 21 percent.

Electricity rates in New York City were jackknifing even before Russia’s assault on Ukraine. The blame is falling on spiking prices for fracked natural gas. Left unsaid is that, as in Germany, the closure last year of the area’s lone nuclear plant, Indian Point, is making utilities draw more heavily on the very gas-fired generators whose costs are spiraling. Also largely unremarked, amidst hosannas over wind and solar power’s falling costs, is the halting pace at which green power is actually filling the breach, belying promises by “safe energy” advocates who helped engineer Indian Point’s closure.

Worse, it is illusory to say that by ramping up renewable energy and energy-efficiency we can pick up the climate slack from closing Indian Point. Why? Because with climate chaos bearing down, every green-energy addition needs to bring about the demise of equivalent fossil fuels. If those additions replace a standing power source that itself replaces fossil fuels, their climate value is zero.

These considerations dim the glow from last month’s record leases for ocean wind farms off Long Island and New Jersey. The need to make up for Indian Point’s energy output will nullify half or more of the hoped-for 7,000 megawatts of offshore wind, badly undermining the legislative commitment to rid the New York grid of carbon emissions by 2040.

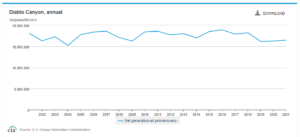

On the opposite coast, the twin Diablo Canyon reactors have for decades provided 2,200 megawatts worth of round-the-clock climate benefit by obviating the need to draw on fossil fuel generators. Shutting them down by 2025 will relegate California’s next 7,000 megawatts of renewables and efficiency (the higher figure is from differences in operability) to stand-ins for Diablo’s lost climate benefit.

The deficit won’t be transitory. Not until every kilowatt on the West Coast comes from zero- or ultra-low-carbon sources can Diablo’s canceled climate benefit be considered superfluous. Until then, the California grid will continuously emit more carbon than it would with Diablo operating.

That moment is approaching but it remains far away. According to data from the US Energy Information Administration, 50 percent of California’s electricity still comes from burning carbon fuels. Hearteningly, this share is 12 points less than it was in 2015, with most of the carbon shrinkage coming from increased solar-photovoltaic supply. But that solar rise, amounting to more than 15 billion kWh annually, is no greater than the amount of carbon-free electricity that shutting Diablo Canyon will take away (17 billion kWh a year, based on 2016-2020 production).

We cannot assume that California’s next solar wave will replace Diablo’s climate benefit, for the simple reason that those solar gains are counted on to push out fossil fuel-burning in buildings, vehicles, and the state’s power grid.

Diablo Canyon’s annual electricity output, shown here, equate to a phenomenal 90.7% average capacity factor from 2001 through 2021, attesting to the plant’s huge climate benefit.

I can hear the objections. Diablo Canyon needs to run at full bore, whereas demand fluctuates. But any excess output can be put to use recharging the millions of batteries California is adding to anchor its grid. Diablo lies atop an earthquake fault. But much of its huge sunk cost went for unprecedented seismic protection that the plant’s owner, Pacific Gas & Electric, failed to budget. (I know this from serving as an expert witness for the California Public Utility Commission’s Division of Ratepayer Advocates in the 1989 proceeding that barred the company from fully recovering its cost overruns.) Guarding Diablo against mishaps or malfeasance takes money. But going forward, the cost of staffing and fuel will be much less than the climate damage its operation prevents.

As an energy-policy analyst, advocate, and organizer for fifty years, I have fought for bicycle transportation, congestion pricing, wind farms, and carbon taxes, in large part to reduce the destructive imprints of coal, oil, and gas.

The climate crisis has exploded ahead of schedule, not as distant warnings but as actual fires, floods, and the global sea-level rise. Meanwhile, Diablo and other US nuclear plants long ago shed their teething problems to become solid climate benefactors, faithfully churning out electricity without combusting carbon fuels.

Others can debate whether to build new nuclear plants to combat the climate crisis. But no one can deny that letting existing reactors like Diablo Canyon remain in service keeps fossil fuels in the ground and their carbon emissions out of our atmosphere. We ignore that benefit at our peril.

Komanoff, author of the treatise Power Plant Cost Escalation, represented New York State and California consumer agencies in opposing rate hikes to pay for reactor cost overruns in the 1970s and 1980s.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Note: The day after posting this, I talked about my Nation article with Left Business Observer’s Doug Henwood on his weekly podcast. (My part starts at 30:18 and goes for a little over 20 minutes.) The conversation is lively and adds further context to the importance of and rationale for continuing to run functional U.S. nuclear power plants.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- …

- 170

- Next Page »