If Gov. Newsom is willing to just toss our emissions goals by rewarding car ownership and gas tax holidays for no reason other than to get re-elected in the safest blue state then it’s settled that California leaders were just virtue signaling about global warming the whole time.

— Darrell Owens (@IDoTheThinking) March 25, 2022

Of the myriad motorist giveaways now being rushed into place around the U.S., none sting like California’s. I share Darrell Owens’ tweeted dismay, not just because California is so reliably blue but because Gov. Gavin Newsom’s proposed car-cash payments point to a troubling fragility in the state’s clean-energy leadership.

The specifics of the so-called relief plan are still being worked on. But the basic shape is expected to hew to the contours posted by Newsom’s office this past week and shown further below: $9 billion in payments to households of $400 per registered car (limit of 2 per family) and just $2 billion to make transit cheaper.

While a per-vehicle stipend isn’t quite as environmentally loathsome as the gas and diesel tax “holidays” already rolled out in Georgia and Maryland and being readied elsewhere (NPR has a useful digest), California’s nearly 50-year record at the forefront of cleaner energy might have suggested other, greener approaches.

I know that record well. Not long ago, I did a study comparing California’s rate of decarbonizing its economy to the rest of the country’s. I found that from the mid-1970s to 2016, California drove down its use of fossil fuels per unit of economic activity nearly 20 percent faster than the other 49 states. Had those states matched California’s pace, I calculated, the country would now, each year, be eliminating 1,200 megatonnes of CO2, an amount equivalent to the carbon emissions from our entire fleet of passenger cars.

I know that record well. Not long ago, I did a study comparing California’s rate of decarbonizing its economy to the rest of the country’s. I found that from the mid-1970s to 2016, California drove down its use of fossil fuels per unit of economic activity nearly 20 percent faster than the other 49 states. Had those states matched California’s pace, I calculated, the country would now, each year, be eliminating 1,200 megatonnes of CO2, an amount equivalent to the carbon emissions from our entire fleet of passenger cars.

Those findings became the basis of a 2019 report for the Natural Resources Defense Council, California Stars: Lighting the Way to a Clean Energy Future. My NRDC co-authors and I credited a host of actors: Gov. Jerry Brown (1974-82, 2010-18), for imbuing an energy-efficiency ethic throughout the machinery of state government; Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger (2003-10), who lent “Terminator” cred and financial support to solar power; and, above all, the thousands of resourceful and devoted state employees who developed and oversaw a kaleidoscope of performance standards that embedded energy efficiency into appliances, equipment and buildings.

Alas, California’s energy record also had an un-stellar part: automobiles. “Passenger vehicles continue to be a weak point,” we noted dryly in “California Stars,” as the state’s consumption of motor fuels grew faster than the rest of the country’s during 1975-2016 (albeit a tad more slowly per unit of GDP). We listed many factors but omitted the most fundamental: California’s vaunted green ethos didn’t include recognition of, and resistance to, car-dependent transportation.

Consider that the day before yesterday, in New York, a coalition of transit, environmental and economic-justice organizations declared their opposition to a possible statewide gas tax holiday “because it does little to help those New Yorkers most hurt by rising prices, takes revenue away from needed road and transit investments and completely contradicts New York’s climate goals.” The groups, who have long worked in concert for safe streets, congestion pricing and better transit, pointed to rising prices for energy (electricity and heating fuels, not just gasoline), food and housing and called for targeted state aid to lower-income households.

Read it and weep: Gavin Newsom’s proposed give-away to California car-owners.

If similar noises are being made in Los Angeles or San Francisco, they aren’t yet audible in New York. Nor do we know what California’s iconically green ex-governors would have done in the face of $5 or $6 gasoline. (The state’s anti-smog rules and carbon cap-and-trade program lead to unusually pricey motor fuels.) I’d like to believe they would have used the gas-price “crisis” as an opportunity to speak inconvenient truths about driving, fossil fuels and climate stewardship. Perhaps Brown would have harkened back to his seventies self and encouraged Californians to voluntarily curtail the share of their driving that is particularly mindless and unnecessary. Schwarzenegger, who earlier this month made an extraordinarily empathic antiwar video appeal to Vladimir Putin’s subjects (“I love the Russian people. That is why I have to tell you the truth.”), might have connected less driving and fuel conservation to patriotism and manliness.

While Newsom lacks those predecessor’s strong personal stamps, he doesn’t lack for imaginative staff. Think of the good the state could do for economic justice and climate protection with the $9 billion he’s handing car-owners.

The most obvious scheme is to apply that money to reduce the state sales tax, a stunningly regressive tax. California’s 7.25% state sales tax brings in around $45 billion annually, according to Tax Foundation figures ($42.7 billion in FY 2020, the most recent figure available), suggesting that $9 billion worth of lower sales taxes would enable the state to cut the rate by one-fifth, to a little under 6%. That change would give relief to every Californian, and disproportionately to poor and working families, without rewarding automobile use and dependence. And it would align nicely with The Economist’s insistence yesterday that “Governments should support household incomes instead … of cutting fuel taxes.”

(Sales tax swaps aren’t exactly novel in environmental discourse. Washington state’s I-732 initiative would have used revenue from a $20/ton carbon tax to cut the state sales tax — the nation’s steepest — by one percent; it was defeated, in 2016, when some climate hawks derided it as, somehow, pro-corporate. Two decades earlier, I published an op-ed calling for a nickel-a-mile charge on driving in Long Island, NY, with the proceeds paying for a 3 percent cut in Nassau and Suffolk Counties’ sales tax.)

M.I.T. Dept of Urban Studies alum Joan Walsh is a board director of AC Transit in Oakland, CA.

In a different vein, folks in the bicycling circles I inhabit are touting free e-bikes rather than car-based giveaways as a means to cushion the pain of high gas prices while helping spur people away from automobiles. The same $9 billion would allow Sacramento to issue e-bike rebates of $300 each to of the roughly 30 million Californians of bicycling age (say, 10 to 80). Making the rebates tradeable would bend to two realities: not everyone can or will use a bike — even one with electric assist — and supplies are constrained. The latter factor suggests that the rebates should remain valid for several years.

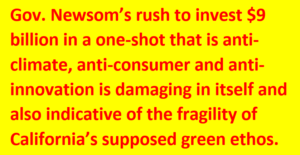

Doubtless, there are other productive ways California could distribute $9 billion in economic relief. What makes the planned automobile giveaway so dispiriting is that for half-a-century the state has done so much in green energy and electricity, outside of the transportation sector, that is pro-climate, pro-consumer and innovative. Gov. Newsom’s rush to invest $9 billion in a one-shot that pulls in the opposite direction is damaging in itself and also indicative of the fragility of California’s supposed green ethos.

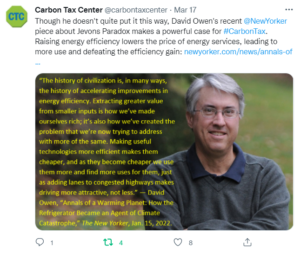

Owen’s article, which is well worth reading for its narrative power and climate relevance as well as its iconoclasm, was his latest exposition of Jevon’s Paradox, the phenomenon by which increases in energy efficiency lower the price of “energy services” and thus lead to more use, undercutting the efficiency gain. The antidote, of course, is to ensure the energy services — cooling, travel, lighting, and so forth — don’t plunge in price by raising the price of energy provision, as I pointed out a decade ago in a post in Grist,

Owen’s article, which is well worth reading for its narrative power and climate relevance as well as its iconoclasm, was his latest exposition of Jevon’s Paradox, the phenomenon by which increases in energy efficiency lower the price of “energy services” and thus lead to more use, undercutting the efficiency gain. The antidote, of course, is to ensure the energy services — cooling, travel, lighting, and so forth — don’t plunge in price by raising the price of energy provision, as I pointed out a decade ago in a post in Grist,

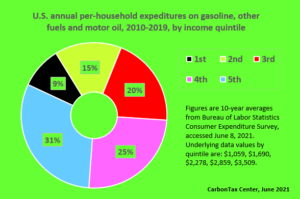

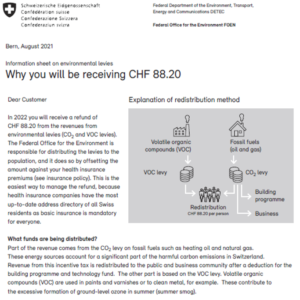

To be clear, CTC has no qualms about raising taxes on the very-affluent as well as the super-rich to make a better society. But raising taxes on the working poor and the beleaguered middle class is another matter entirely. And to the extent that the carbon tax under discussion is meant as a pay-for — literally, to pay for improving America’s physical and social infrastructure — less money will be available for dividends. It’s one thing to set aside a few percent of carbon fee revenues to pay for worker and community transitions, as outspoken climate hawk Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI)

To be clear, CTC has no qualms about raising taxes on the very-affluent as well as the super-rich to make a better society. But raising taxes on the working poor and the beleaguered middle class is another matter entirely. And to the extent that the carbon tax under discussion is meant as a pay-for — literally, to pay for improving America’s physical and social infrastructure — less money will be available for dividends. It’s one thing to set aside a few percent of carbon fee revenues to pay for worker and community transitions, as outspoken climate hawk Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI)