Since April, when President Biden committed the United States to sweeping cuts in greenhouse gas emissions, climate advocates have tried to figure out how he could fulfill his goal of a 50 percent reduction from 2005 levels by 2030.

Their talk is not of a government-led Green New Deal — too hot for a skittish Congress — but of a tapestry of GND-ish policies, many of them wonky. Heading the list are schemes to shovel government cash to utilities that shut down coal- and gas-fired power plants, and to motorists who go electric.

The 37% reduction we estimate for Biden’s Build Back Better package would be a major achievement. 50% will require a robust carbon tax.

There’s sense in these and the other policy pieces, just as there’s logic in refraining from the one overarching policy that could lead the way to the deep cuts Biden is seeking: an economy-wide carbon tax. Giving businesses and households money to go green is more palatable, though less potent, than charging them for burning carbon.

But it’s fair —imperative, actually — to ask if the numerical cuts being attached to those programs actually add up to 50 percent. We don’t think they do; the hill is too steep. Compared to pre-pandemic (2019) carbon emissions, Biden’s goal entails a massive cut, 42 percent, in under a dozen years.

Decarbonizing on that kind of scale falls outside the bounds of the possible without a stiff carbon emissions price. Our purpose here is to show why, and also point a way around.

1.

To kick off this discussion, consider Robinson Meyer’s June 2021 Atlantic article, A “green vortex” is saving America’s climate future. Its big idea was that “decarbonization by doing” — deploying more electric cars and more grid storage systems and more solar panels — is driving down these low-carbon technologies’ costs, naturally leading to more deployment and increasingly kicking fossil-fueled cars and power plants to the curb.

It’s an attractive if familiar notion, this “green vortex.” Sit back, let green energy grow cheaper and bigger, and watch carbon emitters fade to black. But Meyer overhypes it. After outlining the high points of U.S. carbon reductions over the past decade, he states:

Under America’s new Paris Agreement pledge, the country will need to double the pace of its emissions decline over the next decade. Whatever we’re doing right, we’re soon going to have to do it twice as fast. So we’d better figure out what it is. (emphasis added)

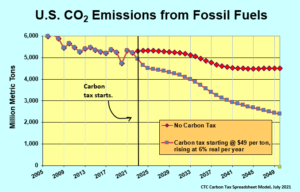

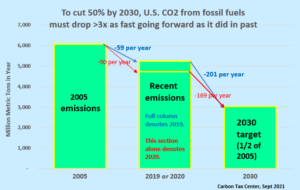

We posed these questions to Meyer, after running calculations on U.S. CO2 emissions from fossil fuel burning. By our count, which is fully detailed in our carbon-tax spreadsheet (see link, three paragraphs below), those emissions totaled 6,070 megatonnes (million metric tons) in 2005 and 5,250 megatonnes in 2019. That computes to 60 fewer megatonnes each year. The task ahead — dropping another 2,215 megatonnes to slim down to 3,035 (half of the 6,070 benchmark) — requires that from 2019 to 2030 we purge 200 megatonnes each year —3.4 times the annual rate of shrinkage from 2005 to 2019.

Extrapolating from 2020 emissions makes the 2030 target look achievable. We don’t recommend it.

In Meyer’s telling, thanks to the green vortex we’ll manage to double our established pace of decarbonization. He might be right. But what if doubling our average annual decline in emissions from 2005-2019 won’t fulfill Biden’s pledged 50 percent cut by 2030? What if it only yields a 35 percent reduction from 2005 emissions, the standard benchmark? What if cutting emissions 50 percent requires that from now to 2030 future U.S. emissions must come down three to four times faster than they did in 2005-2019?

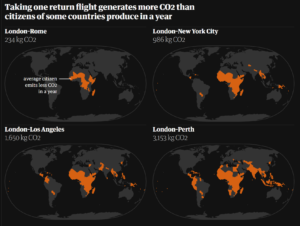

(Perhaps Meyer, who didn’t reply to our email, used 2020 rather than 2019 as his goalpost. That would give him his “doubling,” but meaninglessly. A year that completely upended energy commerce — in which U.S. air travel fell by a third, for example — might be defensible as a new goal post, but not as a basis for computing a new downward trend.)

2.

To grasp how hard it will be for the Biden administration to bend the emissions curve sharply downward without a carbon tax, let’s look at key sectors. A good tool for that is the national carbon-calculator spreadsheet maintained by the Carbon Tax Center (downloadable 3 MB xls).

The Biden plan’s centerpiece is an idea that has become a darling of climate hawks, the Clean Electricity Performance Program. It’s a $150 billion scheme to decarbonize U.S. electricity generation by paying utility companies to replace coal- and gas-fired plants with carbon-free power from wind, solar, biomass or nuclear sources.

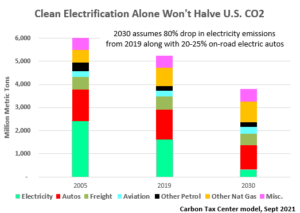

Just over 30 percent of U.S. carbon emissions came from the power sector in 2019, down from 40 percent in 2005, a noteworthy drop that accounted for most of the reductions that Meyer touted in The Atlantic. Let’s assume, as do the White House and its climate allies, that the CEPP’s cash incentives leverage falling prices of solar and wind electricity to achieve the canonical goal of eliminating 80 percent of 2019 power sector carbon emissions by 2030.

The complementary, longer-standing climate policy cornerstone, to “electrify everything,” rests on the eminently reasonable premise that decarbonizing electricity is simpler than mass-producing low-carbon versions of gasoline, natural gas and other carbon fuels. Our calculations optimistically accelerate the uptake of electrified transportation by five years by having the electric shares of cars, trucks and planes in use in 2030 reach levels that in our opinion otherwise aren’t likely until 2035: 20-25 percent for autos, 11-12 percent for trucks and 4 percent for airliners. Those shares are pretty aggressive for 2030, considering that vehicle fleets turn over relatively slowly.

The carbon reductions from this scenario are creditable. With electricity 80% decarbonized and electric vehicles advanced by five years, U.S. CO2 emissions from burning fossil fuels would be 35 to 40 percent less in 2030 than they were in 2005. The reduction, more than two million metric tons of CO2 a year, would qualify as by far the greatest extinction of carbon pollution in history.

But why isn’t the reduction 50 percent? Reason #1 is ever-burgeoning travel. Unless policy interventions like road pricing, public transit and density-friendly upzoning can take root on a grand scale — unlikely in just a decade — the emission reductions from hastening electric transportation will largely be offset by more travel, especially as vehicles on our roads grow ever bigger and more power-demanding.[1]

To be sure, our calculations omit other wonky but potentially potent forms of decarbonization such as widespread replacement of gas furnaces by electric heat pumps. Nor do they incorporate low-hanging fruit from reducing the number two greenhouse gas, methane, both via process capture and as a concomitant to phasing out this fossil fuel altogether.

But we should also be mindful that our most crucial assumption — that we’ll double electricity generation’s carbon-free share from 40 percent today to 80 percent by 2030 — is far from assured. Assume that our aspirational 80 percent carbon-free 2030 electricity comes as 24 percent solar photovoltaics, 32 percent wind, and 24 percent combined from nuclear, hydro-electricity and biomass.[2] Getting to 24 percent solar demands that between now and 2030 we install solar cells three-and-a-half times as fast as we have in any three-month period to date,[3] a task that could easily be sidelined by any number of issues involving supply bottlenecks, permits and certifications.

And if that’s not daunting enough, consider that for wind power to contribute its assigned 32 percent, we’ll need to add the equivalent of 75,000 giant wind turbines rated at 5 MW each[4] to America’s landscapes. Numerically, that equates to 25 turbines per county in the U.S. — a formidable task even if America’s NIMBY culture could somehow be conquered. And all of these targets will be even larger if, as seems likely, the CEPP holds down electricity prices, neutralizing what would otherwise be a helpful brake on demand for power.

3.

Since April, we’ve combed policy papers and journalism about fossil fuel emissions for an accounting of cuts that together might meet the Biden 50% target, or at least come close.

The best compilation we found is a policy brief signed by 20 mainstream and environmental justice organizations and released earlier this month by the Center for American Progress.[5] It’s crisp and precise, as is the Sept. 17 write-up, In the Democrats’ Budget Package, a Billion Tons of Carbon Cuts at Stake, by Inside Climate News journalist Marianne Lavelle, that linked to it.

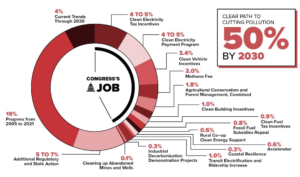

Graphic, courtesy of Center for American Progress. Link in text.

The above graphic from the CAP brief (downloadable pdf) gives a good overview. Since it’s a lot to take in, we’ve broken it into three pieces.

- Fourteen policies included in Biden’s Build Back Better Act, summing to reductions of 22%. We’ve already covered the three largest, pertaining to clean electricity and electric vehicles. They sum to a 22% reduction from 2005 emissions. We haven’t checked the individual numbers, but the overall figure appears solid.

- “Additional Regulatory and State Action,” assigned a reduction range of 5%-7%.

- Two ongoing trends summing to reductions of 23%. The item at far left, 19%: Progress from 2005 to 2021, is supposed to denote the fall in U.S. greenhouse gas emissions from the 2005 baseline. The companion entry at the top, 4%: Current Trends Through 2030, applies forward from 2021. Together, these items purport to deliver large emission reductions without any new policies — along the lines of Rob Meyer’s “green vortex.”

The percentages credited to the three pieces would indeed carry the Biden plan across the 50 percent reduction threshold. But item #2, unspecified regulatory and state action, is vague and squishy. Worse, #3, “ongoing trends,” is numerically questionable. The CAP policy brief projects that 2030 emissions will be 23 percent below 2005 levels with no further policy actions (known as “business as usual”). Yet our modeling says that 2030 business-as-usual emissions will be just 13 percent under 2005 — a 10 point difference from CAP.

That’s no petty discrepancy. It’s also hard to parse in a blog setting. In addition, we don’t know how CAP and its partners derived their figures (ours are shown in the carbon-calculator spreadsheet we linked to earlier). All the same, here are our hunches as to why CAP’s forecasted emissions trajectory is much lower than ours:

- Like Meyer in The Atlantic, CAP could be projecting future emissions from pandemic-depressed 2020 emission levels. In contrast, we think this year and next will bring big rebounds.

- CAP may not be accounting for “natural” emissions growth accompanying increased economic activity. Our modeling of business-as-usual emissions has 2030 matching 2019, as decarbonization of electricity is offset by emissions caused by increased travel and industrial activity.

- CAP’s figures cover all greenhouse gases, including methane, forest sequestration of carbon, and other activities, whereas ours only cover carbon emissions from burning fossil fuels, which tend to be less amenable to change.

Our takeaway is that CAP and its partners are straining to be able to validate the ambition in Biden’s Build Back Better Act to cut emissions by 50 percent.

As noted earlier, a 35-40 percent cut from 2005 to 2030 would still be praiseworthy, even monumental. We would take it in a heartbeat, given the parlous state of American politics and governance. Nevertheless, we ought to be candid about what our policy tools can, and can’t, accomplish.

4.

From @carbontaxcenter, Sept 24.

The point of this post isn’t to weaken support for the Biden package. Monumental cuts are absolutely worth legislating. Nor are we seeking to beat the drum for a carbon tax at this juncture. As CTC has stated repeatedly this year, as early as in this April 2 post, the kind of carbon tax needed to embellish those cuts can’t possibly pass Congress in 2021.

We also suspect that even a starter, “proof of concept” carbon tax at this time will prove to be a poor idea. Passing a carbon tax in lieu of aggressively raising taxes on high income and instituting taxes on great wealth, as several Senate Democratic climate hawks floated today, amounts to budget-balancing on the backs of both the working poor and the beleaguered middle class. It’s inequitable and a terrible template for the really large carbon taxes that progressive Democrats must eventually enact, in the event they ever reach centrist-proof majorities.

Rather, our intent is to try to neutralize the unattainable hype around Build Back Better or other laudable efforts that can’t or don’t include robust carbon pricing.

In case you’re curious, however — we certainly were — we ran our model numbers to see how big a carbon tax would be needed to meet the Biden goal and cut 2005 U.S. CO2 emissions by 50 percent in 2030. Here’s our answer: combined with the CEPP or other measures to ensure 80% decarbonization of electricity (vis-a-vis 2019), along with the same 5-year acceleration of electric cars, trucks and planes we assumed earlier, an economy-wide carbon tax taking effect on Jan. 1, 2022 at a level of $20 per ton (short, not metric) of CO2 and rising each year at $15/ton to reach $140/ton in 2030, would do the trick.

Addendum, Sept 27: Our brand-new follow-on post, Why the Carbon Tax Center Questions the Latest Carbon Tax Talk, elaborates on our critique of the current carbon-tax trial balloon discussed directly above.

[1] Compared to 2005, CO2 emissions in 2030 in this scenario will have fallen by only 23 percent for cars and 9 percent for trucks while increasing by 18 percent for planes, even with accelerated electrification. Another factor holding back emissions progress is increased use of natural gas, as cheap fracked gas finds abundant uses in industry and heating.

[2] The 24 percent combined electricity share for nuclear, hydro and biomass assumes that 2030 generation from those sources remains at current levels. (Their share shrinks slightly because total electricity production rises somewhat; see next footnote.)

[3] Our modeling projects that without a carbon tax, U.S. electricity generation will rise from 4,160 terawatt-hours (TWh) in 2019 to 4,800 TWh in 2030, with around a fourth of the increase attributable to electrified transport. Solar’s 24% share of that, 1,153 GWh, requires nearly 900 GW of installed solar capacity, assuming that a GW of solar produces around 1.3 TWh of electricity in a year, for an average capacity factor of 15%. From several sources, including this recent report by the Solar Energy Industries Association, U.S. installed solar at the end of 2020 was around 100 GW. To grow to 900 GW by the end of 2030, the U.S. solar sector would have to add 800 GW over 10 years, or 80 GW a year. From this report by Wood-McKenzie, the U.S. installed 5.7 GW in 1Q 2021 — a 1Q record — which implies an annual rate of 23 GW.

[4] Assuming an average capacity factor of 35%, wind power’s assumed 32% share of U.S. 2030 generation, 1,537 TWh, requires 500 GW of installed capacity, for a roughly 380 GW increment over end-of-2020 capacity of 122 GW, per U.S. DOE. We optimistically assume an average new-turbine size of 5 MW, although an Internet check on Sept 16, 2021 suggests that the U.S. has no operating wind turbine as large as 5 megawatts (see Windpower Monthly’s Ten of the Biggest Turbines). The U.S. has 3,006 counties.

[5] “The Climate Test: The Build Back Better Act Must Put Us on a clear path to cutting climate pollution 50% by 2030.” Statement, “20 Groups Call on Congress To Pass the ‘Climate Test.’” 4-page policy brief (pdf).