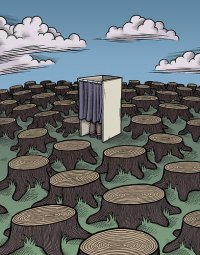

Are cracks appearing in the United States Climate Action Partnership?

How long can USCAP keep up the appearance of agreement on the need for cap-and-trade when there are disagreements within the USCAP membership regarding such fundamental issues as whether a carbon tax is preferable to cap-and-trade and whether allowances should be auctioned or given away as windfalls based upon past pollution?

A December 16 article in the Miami Herald, Cleaning Up the Climate, suggests that tensions within USCAP are beginning to be difficult to ignore. The article noted that Lewis Hay, chairman and chief executive officer of FPL Group (Florida Power & Light), is a supporter of what he euphemistically calls a carbon fee. According to the article:

A December 16 article in the Miami Herald, Cleaning Up the Climate, suggests that tensions within USCAP are beginning to be difficult to ignore. The article noted that Lewis Hay, chairman and chief executive officer of FPL Group (Florida Power & Light), is a supporter of what he euphemistically calls a carbon fee. According to the article:

At one energy conference, Jim Rogers, Duke Energy’s chief executive, noted that Hay ”is saying fee but he means tax.” Hay responded that if his colleagues wanted to fight, "I have a Jerry Springer bouncer backstage.”

Again according to the article, Hay “erupted with an uncharacteristically irate outburst” when a Senate subcommittee approved the Lieberman-Warner legislation that includes provisions creating a cap-and-trade program that gives away some of the allowances to utilities.

Hay believes that giveaways would favor the polluters. Better for the government to auction off the credits, so each utility need buy only what it needs. Hay issued a statement saying the bill "would reward the country’s biggest emitters of carbon dioxide with billions of dollars of free allowances that they don’t need. . . . That’s like giving a bigger rebate to those of us who dump the most trash on our sidewalks.”

Rogers at Duke Energy maintains that the big coal plants need a lot of free allowances to start off, or their customers might be unduly burdened by dramatically higher electric bills.

Meanwhile, the Natural Resources Defense Council urges senators to "reduce the total amount of emissions allowances polluters are given for ‘free.’" NRDC is apparently not arguing that all allowances should be auctioned, but at least it wants to limit the windfalls to industry.

Tensions will inevitably increase as USCAP begins to move past its broad statement of principle and recommendations. In fact, in an October 23 letter from USCAP to Senators Lieberman and Warner, USCAP explicitly noted that it does not yet have a position on a number of fundamental issues:

The Act includes much more detailed provisions than contained in the Call for Action. USCAP members are continuing to discuss the issues raised by a number of these provisions, such as:

• Scope of coverage and complementary policies and measures.

• Sector-specific emission reduction timelines and targets.

• Allocation of allowances.

• Cost containment measures.

• Credit for early action.

• Domestic offsets.

• International offsets.

• Relationship of state and federal GHG programs.

• Implementation of the GHG registry.

• Addressing disproportionate economic impacts.

It’s going to be interesting watching USCAP attempt to find common ground on issues such as the allocation of allowances. Will it support the windfalls in the current draft of Lieberman-Warner (see Friends of the Earth analysis)? How will it address “disproportionate economic impacts”? Will USCAP recommend auctioning all allowances and returning all of the revenues to those who incur the costs of cap-and-trade (similar in some ways to a revenue-neutral carbon tax)? Will it recommend an increase in the already huge windfalls to polluters included in Lieberman-Warner? Or, will it be unable to reach a consensus? Stay tuned.

Photo: Terry Bain / Flickr

The most recent poll, a

The most recent poll, a  With his speech today, Mayor Bloomberg joins former Vice-President Al Gore as the nation’s leading advocates of a carbon tax to cap and reduce carbon emissions from fossil fuels. French President Nicolas Sarkozy

With his speech today, Mayor Bloomberg joins former Vice-President Al Gore as the nation’s leading advocates of a carbon tax to cap and reduce carbon emissions from fossil fuels. French President Nicolas Sarkozy  "We need to profoundly revise all of our taxes… to tax pollution more, including fossil fuels, and to tax labour less."

"We need to profoundly revise all of our taxes… to tax pollution more, including fossil fuels, and to tax labour less." (The quote is from Section 4,

(The quote is from Section 4,  Today Dingell posted on his Web site a

Today Dingell posted on his Web site a

These claims are a bit overstated. More probably there will be a single-digit increase in traffic speeds, a one percent drop in emissions citywide, and perhaps a $400 million revenue infusion for a transportation system whose annual costs top $30 billion.

These claims are a bit overstated. More probably there will be a single-digit increase in traffic speeds, a one percent drop in emissions citywide, and perhaps a $400 million revenue infusion for a transportation system whose annual costs top $30 billion.