For a moment last week it looked like the New York Times was heeding CTC’s summons to tax carbon emissions as a way to make faltering clean-energy projects profitable.

NY Times op-ed by David Wallace-Wells, Jan. 10, 2024. His “missing profits” aren’t the same as ours.

The come-on appeared in the headline for an opinion piece, Missing Profits May Be a Problem for the Green Transition, by the Times’ climate columnist David Wallace-Wells. MISSING PROFITS! Was Wallace-Wells pursuing the idea I floated two months ago in a CTC blog, that a U.S. carbon tax could lift the prevailing price of grid power by enough to offset the cost creep that is killing off off East Coast wind and solar projects along with an innovative nuclear power venture in Idaho?

Not quite. The “missing profits” in the Times column did not refer to the revenue boost that carbon-free power projects should but don’t get for the climate benefit they create by keeping fossil fuels in the ground. Rather, it referred to collapsing returns inflicted on renewable energy projects by higher interest rates, stretched-out schedules and cost escalation endemic to first-of-a-kind projects like enormous offshore wind turbines (East Coast) and small modular reactors (Idaho).

Nevertheless, “missing profits” is a keeper phrase. Though it’s less poetic than “gainsharing,” the neologism we deployed in that Nov. 10 post (Gainsharing: Carbon Taxes Can Put Clean Energy Back in the Black), the phrase is more to the point: The lack of robust carbon pricing manifests as missing profits that beset every project, policy and gesture that promises to reduce use of fossil fuels and, thus, to avert and reduce carbon emissions.

Leave the idea, take the expression, “Godfather” movie character Pete Clemenza might have said.

What was the idea, then, in Wallace-Wells’ Times column? Mostly that the prospective profits from wind and solar projects are downright meager compared to returns on oil and gas supply investments.

True enough, and unsettling. But the antidote advanced in the column is almost diametrically opposite ours. We want a robust U.S. carbon price “to put clean energy projects back in the black.” In contrast, Uppsala University (Sweden) geographer Brett Christophers, the avatar of Wallace-Wells’ column, wants “public ownership of the power sector.”

Yes, but which price is wrong? Christophers writes in his forthcoming book that renewables cost too much and need public investment. We say *fossil fuels* are priced *too low* and require carbon pricing.

I haven’t read Christophers’ new book, The Price Is Wrong — its publication is set for March. But its contours seem clear from Wallace-Wells’ column and from Christophers’ own NYT guest essay last May, Why Are We Allowing the Private Sector to Take Over Our Public Works?

In that essay, Christophers took dead aim at the Biden administration’s signature climate achievement, the Inflation Reducation Act. “The I.R.A. will help accelerate the growing private ownership of U.S. infrastructure and, in particular, its concentration among a handful of global asset managers,” he warned.

“It is wrong,” Christophers continued, to cast the I.R.A. and other Biden legislation as “a renewal of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal infrastructure programs of the 1930s.”

The signature feature of the New Deal was public ownership: Even as private firms carried out many of the tens of thousands of construction projects, almost all of the new infrastructure was funded and owned publicly. These were public works. Public ownership of major infrastructure has been an American mainstay ever since. [I]n political-economic terms, Mr. Biden, far from assuming Roosevelt’s mantle, has actually been dismantling the Rooseveltian legacy. (emphasis added)

That may be, though claiming Biden is dismantling FDR’s legacy is quite a stretch. For his part, Wallace-Wells summarized the conundrum of green power’s newly spiking capital and interest costs as follows:

For Christophers, this is a challenge that implies its own solution: public ownership of the power sector. If all that stands between our bumpy “mid-transition” status quo and an abundant clean-energy future for all is an initial hurdle of investment, why strain to extract that investment from private investors who’d prefer to invest elsewhere?

Again, perhaps. But treating renewables’ upfront-cost hurdle as a minor matter to be tweaked, as Wallace-Wells suggests, has an air of whistling past the graveyard. What if the findings from the International Energy Agency and Bloomberg New Energy Finance, touted by Wallace-Wells and countless others, that new wind and solar arrays pencil out cheaper than equivalent electricity generated with coal or methane, are simplistic or plain wrong?

To his credit, Wallace-Wells allowed in his column that U.S. public power agencies traditionally have been “obstacles to a rapid transition [from fossil fuels]” rather than “models of hyperdecarbonization.” But it’s also true that some entities of government, including New York State, have strong public works traditions. Indeed, some historians view Franklin D. Roosevelt’s tenure as governor as a testing ground for ideas such as unemployment insurance and old-age pensions that his presidency made foundational to the New Deal.

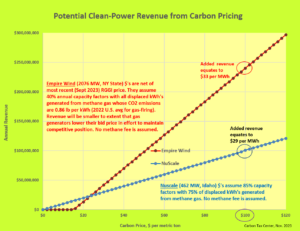

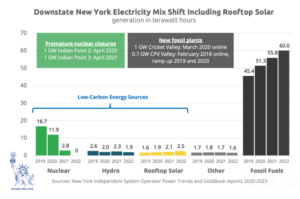

Chart, reprinted from our Nov. 2023 “Gainsharing” post (link in text), has back-of-the-envelope estimates of the “missing profits” clean-energy projects could capture under carbon pricing.

In this light, CTC sees potential in New York’s new (2023) Build Public Renewables Act, which authorizes the NY Power Authority to build and own renewable power projects. At the same time, we’re mindful that public financing of clean power constitutes a subsidy, albeit an indirect one, and that the U.S. tax code already provides considerable subsidies to wind and solar power — subsidies that the I.R.A. extended to the entire electrification effort (EV’s, batteries, transmission, manufacture) of which wind and solar are key components.

Still, the virtues and pitfalls of public investment in clean power are worthy of public conversation, not just in the U.S. but “in the poorer parts of the world,” as Wallace-Wells notes, where hundreds of millions lack access to electricity of any stripe, in part because “capital costs of new infrastructure can be prohibitively high even in the absence of supply shocks and global inflation conditions.”

Our focus at CTC, however, is the United States, home of the world’s most inventive entrepreneurs and its most efficient capital markets. Without shutting the door against public investment, we are tantalized by the possibility that clean power’s cost hiccups could be overcome through robust carbon pricing. Unlike subsidies, carbon pricing won’t “accelerate the growing private ownership of U.S. infrastructure and, in particular, its concentration among a handful of global asset managers” — the specter raised against the I.R.A. by Brett Christophers in his May 2023 Times guest essay.

Carbon pricing doesn’t play favorites and is resistant to gaming. It’s ecumenical, technology-neutral and pervasive. It raises all low-carbon boats — energy efficiency and conservation as well as renewables. Whether it can actually make clean-power projects profitable on a vast scale is a question we at CTC intend to explore.

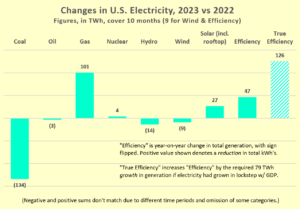

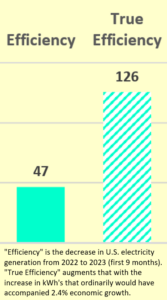

Here we examine the locus of the good news: the 8% drop in electricity generation in 2023 vs. 2022 that enabled the 2% drop in overall emissions despite rises in emissions from transportation and some other sectors.

Here we examine the locus of the good news: the 8% drop in electricity generation in 2023 vs. 2022 that enabled the 2% drop in overall emissions despite rises in emissions from transportation and some other sectors. But the efficiency story doesn’t end there. U.S. economic output wasn’t flat in 2023, it grew by 2.4% over 2022 (per preliminary figures

But the efficiency story doesn’t end there. U.S. economic output wasn’t flat in 2023, it grew by 2.4% over 2022 (per preliminary figures

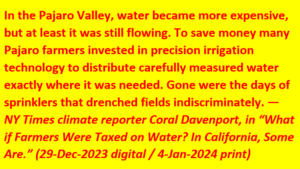

Just as importantly, the growers receive a potent incentive to use available water supplies more efficiently. “Gone were the days of sprinklers that drenched fields indiscriminately,” Davenport writes. “To save money, many Pajaro farmers invested in precision irrigation technology to distribute carefully measured water exactly where it was needed.” (See text box.) Though the article doesn’t mention it, these investments by dozens of individual growers might not have materialized had not all growers been subject to the same incentives to conserve as well.

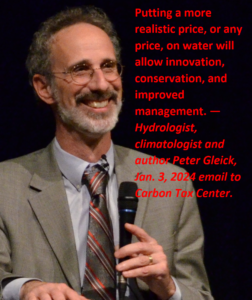

Just as importantly, the growers receive a potent incentive to use available water supplies more efficiently. “Gone were the days of sprinklers that drenched fields indiscriminately,” Davenport writes. “To save money, many Pajaro farmers invested in precision irrigation technology to distribute carefully measured water exactly where it was needed.” (See text box.) Though the article doesn’t mention it, these investments by dozens of individual growers might not have materialized had not all growers been subject to the same incentives to conserve as well. After reading Davenport’s article I reached out to hydrologist, climatologist and water sustainability expert Peter Gleick, whose latest book,

After reading Davenport’s article I reached out to hydrologist, climatologist and water sustainability expert Peter Gleick, whose latest book,

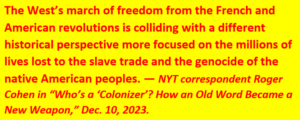

Suppose carbon emissions were taxed in every country. Would that entail colonizing of poor nations by the rich? It could, but only if the carbon-tax wealth — the revenue generated by the tax on carbon emissions — was siphoned off by the rich countries.

Suppose carbon emissions were taxed in every country. Would that entail colonizing of poor nations by the rich? It could, but only if the carbon-tax wealth — the revenue generated by the tax on carbon emissions — was siphoned off by the rich countries.

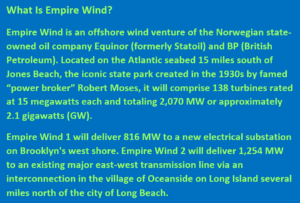

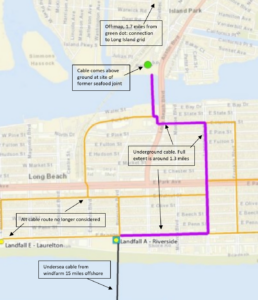

There will be 138 turbines, identical and gigantic. At 387 feet, each turbine blade will be the length of a football field including the end zones. The distance from water surface to blade tip at full height will be 886 feet, roughly the extent of two celebrated Manhattan towers that a century ago were the world’s tallest buildings: the 792-foot Woolworth Building (#1 from 1913 to 1930) and the 1,046-foot Chrysler Building (1930-1931). An even funner fact, from

There will be 138 turbines, identical and gigantic. At 387 feet, each turbine blade will be the length of a football field including the end zones. The distance from water surface to blade tip at full height will be 886 feet, roughly the extent of two celebrated Manhattan towers that a century ago were the world’s tallest buildings: the 792-foot Woolworth Building (#1 from 1913 to 1930) and the 1,046-foot Chrysler Building (1930-1931). An even funner fact, from

The urgency now is far greater. Today, as I was wrapping this post, the New York Times

The urgency now is far greater. Today, as I was wrapping this post, the New York Times

This post, written by renowned eco-journalist Christopher Ketcham and commissioned by and

This post, written by renowned eco-journalist Christopher Ketcham and commissioned by and