Note: This post was amended on July 6 to include @bobinglis’s June 30 tweet, shown below.

Maybe we’re grasping at straws. But we see a possible silver lining in this week’s grievous Supreme Court ruling striking down US EPA’s authority to regulate carbon emissions via the Clean Air Act.

The gleam of hope is not that the decision didn’t dismember the federal government’s entire “administrative state” apparatus — you know, the tapestry of rules, regulations and procedures designed to further societal health, safety and accountability. We fear investigative journalist Amy Westervelt may be right that the ruling is a harbinger of steps in that very direction.

What I’m not seeing a lot of people get is that the West Va v EPA verdict is a harbinger. It’s the first step not the death blow. Overstating it obscures that, leaving people thinking it’s all over and ill-prepared for what comes next.

— Amy Westervelt (@amywestervelt) July 1, 2022

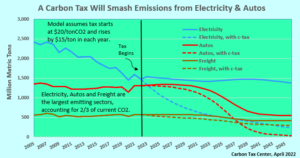

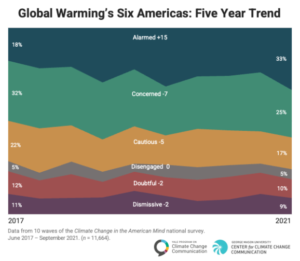

Rather, our thin beam of optimism is the opening the ruling could provide for carbon tax proponents to persuade our fellow climate advocates to lean less on fraught, slow and even quixotic approaches for tackling climate change, and to instead turn increasingly toward carbon taxing as a more-holistic and bulletproof way to bring down stubbornly high carbon emissions, both in the U.S. and worldwide.

In recent years, this space has done battle with what we’ve regarded as inadequate or even illusory climate strategies.

* We’ve criticized the decade-long campaign to divest financial and social institutions from fossil fuels, arguing in our posts and on our evergreen pages that capital will easily find ways to finance whatever legal product consumers demand, especially a product so economically and psychologically fraught as gasoline.

* We’ve hit back at the IMF’s unfortunate labelling of fossil fuels’ vast externality costs — both climate damage and immediate human-health harms — as “subsidies,” for fostering the fantasy that citizens need only stop their governments from bestowing public tax dollars on fossil fuel companies, and Big Carbon will crumble and wither away.

* We’ve even questioned the keep-it-in-the-ground movement, arguing, heretically, that “Oil that doesn’t flow to refineries through the Dakota Access Pipeline [to take one example] will instead come from somewhere else – Kuwait or Texas or a hundred other places – to be burned in cars, trucks and planes.” Our movement’s focus, we’ve argued, must be demand, not supply.

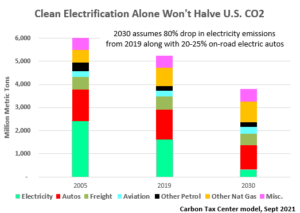

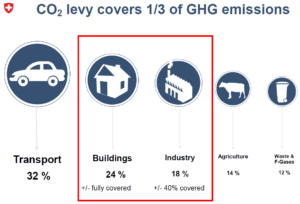

* And we’ve looked long and hard at the climate value of environmental regulation — the very approach the Supreme Court threw under the bus yesterday. Look at how, a year ago, we contrasted the fabulous success of the 1970 Clean Air Act and its 1977 and 1990 amendments in slashing concentrations of particulates and other harmful pollutants in “ambient air,” with the less-technology-amenable issue of carbon emissions:

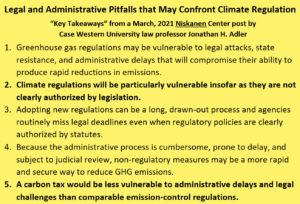

These and similar successes have led many climate advocates to urge similar regulatory pathways to curb carbon emissions. [Yet] regulatory approaches may offer only modest prospects for controlling and reducing emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, for several reasons. For one thing, the absence of antipollution devices for capturing or lowering CO2 emissions limits the scope of technology-forcing regulation. For another, promulgation of regulations is necessarily piecemeal and reactive. Moreover, the regulation-setting and administering process itself is cumbersome, delay-prone and subject to legal challenge by carbon interests.

From Niskanen Center post. Link is in text. We’ve added emphasis to #2 and #5.

We backed up that argument with reasoning from a penetrating paper by Case Western University law professor Jonathan Adler. The sidebar at right has Prof. Adler’s own “key takeaways” from the summary version he published on the Niskanen Center’s website. We highlighted two: A, climate regulations that aren’t clearly authorized by legislation will be particularly vulnerable to legal challenges — as we saw this week, when the six right-wing justices took advantage of the absence of explicit mentions of climate or carbon in the Clean Air Act and its amendments. And B, compared to emission-control regulations, a Congressionally enacted carbon tax should be less vulnerable to such challenges.

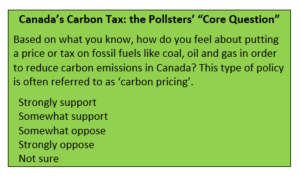

This isn’t to say that a carbon tax is just around the corner. We readily admit that a path to enacting a meaningful federal carbon tax — not a token, Exxon-style levy that damages coal but not oil or gas, but a robust carbon price that can reach triple digits in a half-dozen or fewer years — is almost impossible to discern.

Rather, now that essentially all of the prominent alternatives have been eviscerated or emasculated, it’s time for climate advocates to rethink, and, hopefully, relinquish, their anti-carbon-pricing positions.

The Carbon Tax Center has strived to be a climate team-player. At least since the start of the Trump administration, we’ve acknowledged the near-impossibility of passing a federal carbon tax in the current political configuration, and have instead pulled for less-ambitious but more-achievable (or so they seemed) incremental steps.

Just last fall, we wrote that “There’s logic in refraining from the one overarching policy that could lead the way to the deep cuts Biden is seeking: an economy-wide carbon tax. Giving businesses and households money to go green [instead] is more palatable, though less potent, than charging them for burning carbon.”

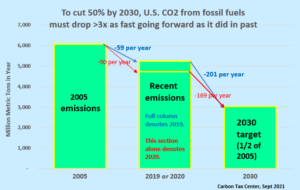

But we’ve also strived to be truth-tellers. That’s why we called that 2021 post, “Without a Carbon Tax, Don’t Count on a 50% Emissions Cut.” And it’s why we’re a little less inclined than some of our climate comrades to go into full mourning over yesterday’s Supreme Court decision .

Supreme Court leaves it up to Congress to act on climate change. That’s OK because Congress can enact a carbon tax and a carbon border adjustment that can make the solution go worldwide. Tax pollution. Un-tax income. Conservatives in Congress, here’s your chance! We need you!

— Former Rep. Bob Inglis (@bobinglis) (R-SC) June 30, 2022

Please also note that unlike the indefatigable Bob Inglis, who bravely fought for carbon pricing as a six-term Member of Congress (1993-1999, 2005-2011) from South Carolina’s 4th District, we’re not calling on “Conservatives in Congress” to push for carbon taxing. We would love it if even a few did, but that ship sailed over a decade ago, as we’ve summarized on CTC’s Conservatives page.

To sum up: Yes, the Supreme Court ruling was ignorant. Yes, it was destructive. Yes, it’s almost certainly a harbinger of worse. But it didn’t demolish policies that were on course to rescue our planet and make Biden a climate hero.

Yesterday’s decision did damage, but maybe it pulled some wool from our eyes as well.

Promising developments like

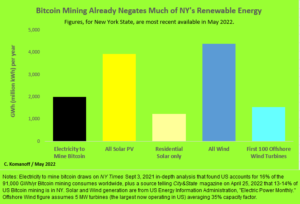

Promising developments like  While New Yorkers are accustomed to thinking of our state as resource-poor, crypto miners are now exploiting half-a-dozen hydro power sites and formerly boarded-up fossil-fuel plants in northern and western New York. One industry source

While New Yorkers are accustomed to thinking of our state as resource-poor, crypto miners are now exploiting half-a-dozen hydro power sites and formerly boarded-up fossil-fuel plants in northern and western New York. One industry source  This isn’t to hold out carbon taxing as a one-bullet crypto killer — we need many bullets for that, the bigger the better — but to illustrate its broad potential to stop frivolous (and in this case imbecilic) new uses of electricity before they can gain a foothold.

This isn’t to hold out carbon taxing as a one-bullet crypto killer — we need many bullets for that, the bigger the better — but to illustrate its broad potential to stop frivolous (and in this case imbecilic) new uses of electricity before they can gain a foothold.

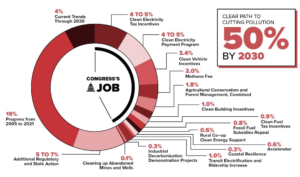

Amen. The failures propping up US carbon emissions are multiple. Not just Senator Joe Manchin, who torpedoed President Biden’s Build Back Better clean-energy legislation. Not just the Senate Republicans, any one of whom could have cast the critical 50th vote. And not just Big Carbon, whose

Amen. The failures propping up US carbon emissions are multiple. Not just Senator Joe Manchin, who torpedoed President Biden’s Build Back Better clean-energy legislation. Not just the Senate Republicans, any one of whom could have cast the critical 50th vote. And not just Big Carbon, whose

Owen’s article, which is well worth reading for its narrative power and climate relevance as well as its iconoclasm, was his latest exposition of Jevon’s Paradox, the phenomenon by which increases in energy efficiency lower the price of “energy services” and thus lead to more use, undercutting the efficiency gain. The antidote, of course, is to ensure the energy services — cooling, travel, lighting, and so forth — don’t plunge in price by raising the price of energy provision, as I pointed out a decade ago in a post in Grist,

Owen’s article, which is well worth reading for its narrative power and climate relevance as well as its iconoclasm, was his latest exposition of Jevon’s Paradox, the phenomenon by which increases in energy efficiency lower the price of “energy services” and thus lead to more use, undercutting the efficiency gain. The antidote, of course, is to ensure the energy services — cooling, travel, lighting, and so forth — don’t plunge in price by raising the price of energy provision, as I pointed out a decade ago in a post in Grist,

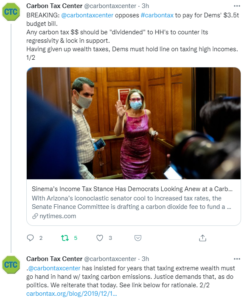

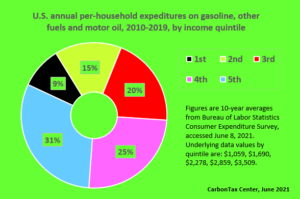

To be clear, CTC has no qualms about raising taxes on the very-affluent as well as the super-rich to make a better society. But raising taxes on the working poor and the beleaguered middle class is another matter entirely. And to the extent that the carbon tax under discussion is meant as a pay-for — literally, to pay for improving America’s physical and social infrastructure — less money will be available for dividends. It’s one thing to set aside a few percent of carbon fee revenues to pay for worker and community transitions, as outspoken climate hawk Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI)

To be clear, CTC has no qualms about raising taxes on the very-affluent as well as the super-rich to make a better society. But raising taxes on the working poor and the beleaguered middle class is another matter entirely. And to the extent that the carbon tax under discussion is meant as a pay-for — literally, to pay for improving America’s physical and social infrastructure — less money will be available for dividends. It’s one thing to set aside a few percent of carbon fee revenues to pay for worker and community transitions, as outspoken climate hawk Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI)