The carbon tax proposal that the Climate Leadership Council unveiled last month upends orthodoxies on both sides of the political divide. It is revenue-neutral, which goes against the desires of many on the Left to invest carbon tax revenues in a “just transition” to clean energy. It distributes those revenues as “dividends” to U.S. families, an income-progressive outcome that frustrates those on the Right who might accept a carbon tax as a way to pay for reducing the corporate income tax, at least in theory.

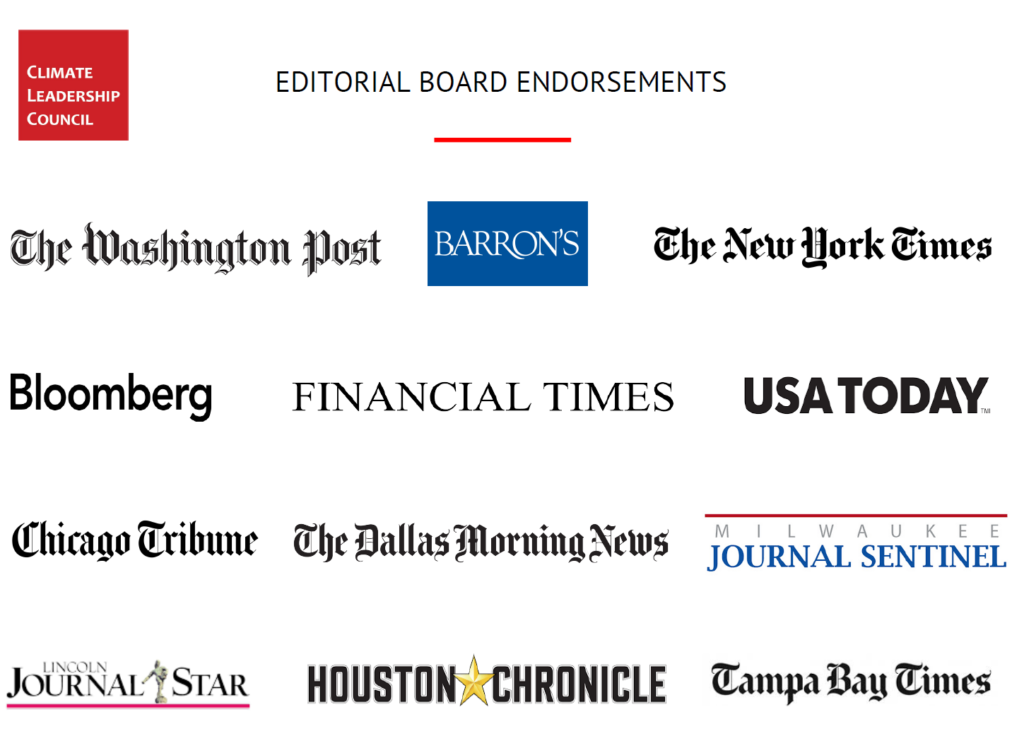

Editorial endorsements for the Shultz-Baker carbon tax proposal, as of March 1.

We at CTC heartily endorsed the council’s proposal in a blog post hours after its release. So did a dozen leading newspapers, including the Dallas Morning News, the Houston Chronicle, the Financial Times and Barron’s, some of which were likely impressed that the CLC rollout was led by GOP icons James Baker and George Shultz, both of whom held multiple cabinet posts in earlier Republican administrations. But that wasn’t good enough for the Wall Street Journal, whose editorial page sometimes reads as if written by the Koch Brothers-financed, climate change-denying Americans for Prosperity. Its Feb. 25 editorial attacking the CLC proposal, The Carbon Tax Chimera, didn’t so much rebut the proposal as excoriate it.

Messrs. Shultz and Baker responded in a letter in the Journal last Friday, We Thought We Would Hit Your Sweet Spot. Their letter isn’t aimed at the Journal’s editors, who are tethered to hard-right climate denialism, but to the paper’s remaining readers who recognize that catastrophic climate change poses risks to their bottom line (and themselves) and are looking for a policy response they can support. In the same spirit, we present this point-by-point rejoinder to the Journal’s editorial by Dr. Peter Joseph, group leader of the Marin County, CA chapter of Citizens’ Climate Lobby. Dr. Joseph is an outspoken advocate for the fee-and-dividend approach to carbon taxing which forms the heart of the CLC proposal.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

1. WSJ: The climate may change but one thing that never does is the use of climate change as a political wedge against Republicans.

Dr. Joseph: Following Sen. John McCain’s 2008 campaign acknowledgment of climate change, it was Republicans who turned climate change into a wedge issue by conflating scientific uncertainty — a necessary and ever-present part of scientific inquiry — with the well-established scientific consensus about global warming. The Journal seems not to appreciate that the Shultz-Baker plan, tailored to appeal to fiscal conservatives, can serve as Republicans’ escape ladder from this untenable position once they let go of the “I am not a scientist” trope and decide to join every other major political party – including conservative — in the Western democracies and get serious about this threat.

2. Also never changing is the call from some Republicans to neutralize the issue by handing more economic power to the federal government through a tax on carbon.

Revenue neutrality with 100 percent of the revenues returned to U.S. families as carbon dividends actually deprives the federal government of more economic power by channeling all the money back to citizens and reserving decision-making power to households, companies and markets.

3. The risk is that Donald Trump takes up the idea, which would hurt the economy with little benefit to the environment.

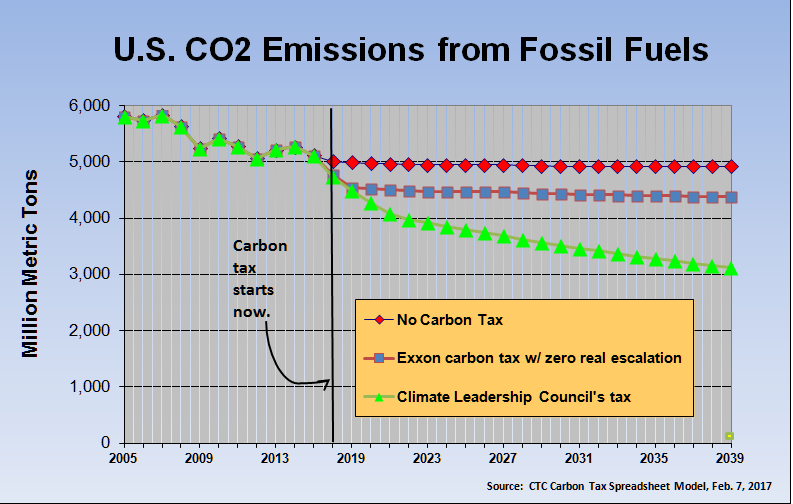

A fully refunded carbon tax will cut emissions with greater efficiency and less economic drag than regulations. It also produces greater environmental benefits and promotes business stability. The Climate Leadership Council estimates that by 2025 its plan will reduce CO2 emissions reductions by 28% below the 2005 baseline, meeting America’s Paris commitment. The Carbon Tax Center, modeling a more robust rise in the tax level after the initial $40/ton, estimates that the council’s plan would, by 2030, reduce our annual CO2 emissions from 2005 levels by 40 percent.

4. Such a tax might be worth considering if traded for radically lower taxes on capital or income, or is [sic] narrowly targeted like a gasoline tax.

Some economists recommend tax swaps, with Republican-leaning economists preferring cuts to the corporate income tax and Democratic-leaning ones favoring cutting the payroll tax. But politics point strongly to the dividend approach. The tax code is so complex, and Treasury Department bookkeeping so labyrinthine, that it’s extremely difficult to pull off a tax swap that’s immune to suspicions that the government is “stealing” the money. Accountability is crucial. Plus, the carbon tax has to rise each year, since it can’t start at the high levels that are required without seeming punitive. This requires the public to trust that the tax revenues will actually come back to them. A dividend like the council’s can win their trust, since the dividend checks rise in concert with the tax level.

5. But in the real world the Shultz-Baker tax is likely to be one more levy on the private economy.

Reinjecting billions directly back into the Main Street economy will act as a stimulant, not a drag. When families, particularly at the lower end, receive money regularly, they spend it. Sectors other than the hydrocarbon industry will benefit, and the predictable glide path toward the low-carbon economy will allow industry to adapt.

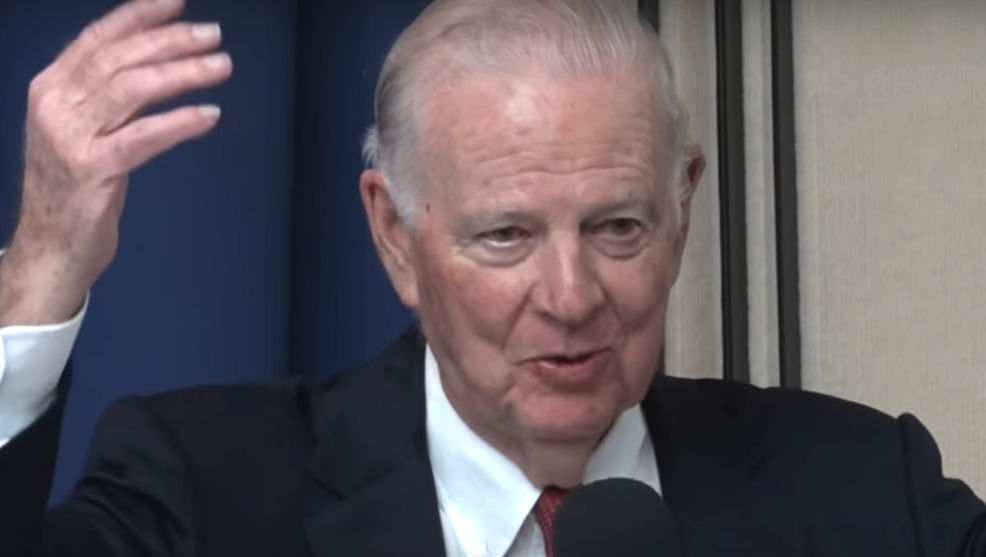

Former Secretary of State & Treasury James Baker, at the Climate Leadership Conference’s Feb. 8 rollout of its carbon tax proposal at National Press Club.

6. Even if a grand tax swap were politically possible, a future Congress might jack up rates or find ways to reinstate regulations.

The carbon tax signal should escalate predictably, and as long as the public receives the funds they won’t be inclined to revolt, since a clear majority will be made better off. As for wealthier households, many will hardly notice that their dividend checks don’t cover their carbon tax bite. Provided the tax levels are robust rather than token, Congress will have no incentive to “jack up rates” later on. Remember, Washington keeps none of the money.

7. Another problem is the “dividend.” A carbon tax would be regressive, as the poor spend more of their income on gasoline and household energy.

Full dividend return converts a regressive policy into a progressive one. The key is the dividend: since wealthier people have larger-than-average carbon footprints (they buy more stuff, live in bigger houses, fly more, etc.), they’ll pay in, while most middle-income and virtually all low-income families will take out. Models show that close to two-thirds of the population comes out ahead with full revenue return via dividends rebate. Citizens will retain the freedom to lower their consumption and use the spread between their carbon dividend check and carbon footprint costs as an incentive to reduce personal emissions and make some money, if they choose, without being required to do so by the government.

8. The plan purports to solve this in part by promising to return the tax to the American public. But the purpose of taxes is to fund government services, not shuffle money from one payer to another. No doubt politicians would take a cut to funnel into renewable energy or some other vote-buying program.

Taxes fund programs, agencies and services that make America great. But a fully refunded “tax” such as the council’s isn’t really a tax if the government doesn’t keep the money. It’s a fee, not intended to generate operating revenue but to correct a market failure. True, politicians might find it difficult to let huge sums slip through their fingers. As then-ExxonMobil CEO Rex Tillerson quipped in a 2009 speech advocating a revenue-neutral carbon tax, “I know that’s hard for a politician to say.” He suggested the tax be called “a refundable greenhouse gas emissions fee.” The U.S. government will return the funds unmolested as required by law.

9. The rebates would also become a new de facto entitlement with an uncertain funding future.

The dividends will rise initially, then level off and eventually — and predictably — decline as the rising fee does its job of lowering carbon intensity. (That decline is another argument against using the carbon revenue for tax swaps or government programs, as the eventual budget shortfalls would require a future Congress to raise taxes.) At the same time, energy from wind and sunlight, whose fuel is free, combined with efficiencies and innovative processes and products, will stabilize or decrease the costs of goods and services. What matters to citizens is their overall household budgets. There will also be savings in healthcare costs as the air gets cleaner, and presumably military expenditures as we wean off unstable sources of foreign oil.

10. Meanwhile, the energy import fee looks like an appeal to Mr. Trump’s protectionist impulses…The idea is an attempt to export U.S. climate and tax policy with the threat of tariffs, which other countries may resent.

The Journal would do well to look more broadly at the council’s border carbon tariff. It’s an incentive to other countries, a tool to ensure a level playing field for U.S. manufacturers, and an act of leadership by the world’s most vibrant economy. A sustainable climate and a habitable earth require controlling global emissions. Without a global carbon price, too many nations will be unable to fulfill the reduction targets they promised in Paris, which are all voluntary. The global economy is the only enforcement mechanism there is. From a practical political standpoint, without a border carbon tariff no carbon charge will ever get through Congress if it disadvantages U.S. exporters.

11. The tax rate would also be influenced by international climate models that have overestimated the increase in global temperature for nearly two decades.

Must the WSJ editorial page continue to cling to this wearisome canard, in the face of year after year of record-setting temperatures? As for alleged IPCC “overestimates,” presumably referring to the alleged “pause” in surface temperature increases, that spurious claim has been thoroughly debunked. The excess retained heat energy has been going into the oceans, where it’s accelerating the disintegration of the polar ice shelves — dams restraining the great land ice sheets —threatening much higher sea level rise than previously predicted and threatening to inundate vast stretches of our nation’s and the world’s coastal areas.

12. A carbon tax is always pitched as “insurance” against climate change, but no one thinks it will change the trajectory of temperatures.

That might apply to an anemic price signal. It hardly applies to a carbon tax that starts at $40 per ton of CO2 and rises from there. The data indicate that most known fossil fuel reserves must remain in the ground to prevent catastrophic warming. Only a robust price signal can enable markets to resist the disastrous allure of trillions of dollars worth of carbon products. A rising fee on carbon emissions is the most powerful lever we have to phase out fossil fuels as fast as practicable.

13. A 2016 paper from the Cato Institute makes the point that insurance policies hedge risks that are well-known, unlike climate change, whose risks are highly uncertain.

The Cato Institute, known for its climate denial, is hardly a source of sound advice. The scientific consensus tells us that the chances that climate change will wreak catastrophic damage on property, let alone ecosystems and civil society, are far greater than the probability that, say, one’s home will be destroyed by fire. Yet every homeowner has fire insurance.

14. Fossil fuels make up about 80% of U.S. energy; solar, wind and hydropower are more expensive and lack the scale to be a viable substitute.

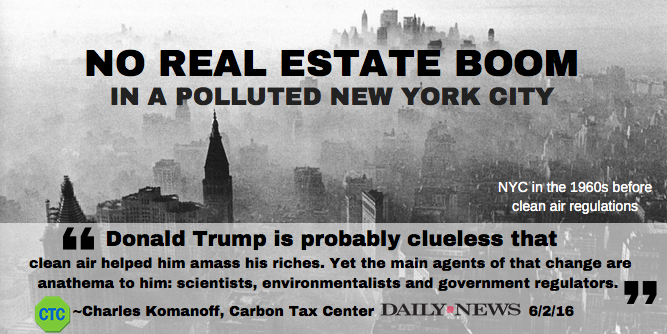

Fossil fuels rose to dominance through political arrangements that externalized the true costs of dumping their combustion products into the atmosphere and oceans. One can argue that these costs were unknown until now. Today to not know is to deny reality. The carbon tax internalizes those costs, rectifying a massive market failure. Yet even without that tax, solar and wind are rapidly gaining market share and grid parity, and there are no limits to the eventual scope of their deployment. A carbon tax will accelerate this transition.

Harvard economics professor Greg Mankiw at the Feb. 8 CLC press conference.

15. Congress has never shown the self-restraint to collect an estimated $1 trillion in taxes and return it to the public. Any Republican who supported a carbon tax can expect no help from Democrats, who won’t restrain the Environmental Protection Agency.

As Secretary Tillerson observed, it is tough for a politician to utter the words “revenue neutral.” The public will have to demand it, and the business community, understanding that climate disasters are terrible for business, must lobby for it. Elected officials will then follow. The Shultz-Baker plan calls for suspending most EPA authority over CO2, an olive branch to anti-regulation interests. Evidence that Democrats and their environmental allies might be willing to relinquish control over the carbon tax revenue stream can be found in the resolution that California’s Democratic-controlled legislature passed last August calling on Congress to enact a revenue-neutral carbon fee and dividend proposal similar to the Shultz-Baker plan.

16. You won’t read this elsewhere, but what’s driven the recent reduction in U.S. carbon emissions is fracking for natural gas, which might never have happened had a carbon tax been in place.

While it’s undeniable that fracked gas contributed to overall reductions bydisplacing dirtier coal, a recent report by the Carbon Tax Center established that since 2005 the combination of electricity savings from efficiencies and increased wind and solar have played a greater part in reducing carbon emissions tha the replacement of coal by gas. Moreover, efficiency, wind and sunlight — unlike fracking — generate zero emissions of methane, which is also a potent greenhouse gas.

17. Human ingenuity and prosperity are the best insurance against climate change.

Perhaps. But even human ingenuity is hard pressed to overcome broken markets that fail to price carbon emissions’ damages. As Harvard economics professor Gregory Mankiw pointed out in the CLC press conference rolling out the carbon dividend plan (@32 min), a carbon tax is as close to a silver bullet as there is, precisely because it engages the enormous power of money and markets, with minimal risk, in a nonpartisan way. The WSJ should support it.

Dr. Joseph may be reached at pjmd1

Our long-building climate crisis is already materializing as drowned coasts, punishing droughts, vanishing glaciers—and political upheaval. At its root is a century-old lie: market prices for gasoline and other fossil fuels that do not factor in the damage from burning them.

Our long-building climate crisis is already materializing as drowned coasts, punishing droughts, vanishing glaciers—and political upheaval. At its root is a century-old lie: market prices for gasoline and other fossil fuels that do not factor in the damage from burning them. But government policy revolves around trade-offs, and on balance the Council’s carbon tax is worth supporting. After all, well over 80 percent of the Clean Power Plan’s targeted reductions for 2030

But government policy revolves around trade-offs, and on balance the Council’s carbon tax is worth supporting. After all, well over 80 percent of the Clean Power Plan’s targeted reductions for 2030

Erik had a

Erik had a

Leaving aside the fact that the global renewables revolution already has a leader (hint: it’s Europe’s

Leaving aside the fact that the global renewables revolution already has a leader (hint: it’s Europe’s