How to compensate consumers under carbon pricing (Reuters – Felix Salmon Blog)

Report: Revenue Provisions Could Make 'Regressive' Carbon Tax Neutral

Report: Revenue Provisions Could Make ‘Regressive’ Carbon Tax Neutral (Irish Times)

Doubt and Anger Over Carbon Tax

Doubt and Anger Over Carbon Tax (Connexion France)

Is China's Climate Position Softening?

Is China’s Climate Position Softening? (TNR – The Vine)

Does Cap-and-trade Punish Virtue?

Another question directed to the Carbon Tax Center: Would a carbon emissions cap become an emissions minimum as well as maximum, in effect precluding reductions below the cap level?

A “cap” of the type embedded in the House-passed Waxman-Markey bill (ACESA) is a legislated number of allowances, or permits, corresponding to tons of CO2 to be emitted. If the number of allowances is less than total expected CO2 emissions for that year, the shortfall will create an allowance price sufficient to drive demand down to the cap level. A too-loose cap (where allowances exceed emissions) will cause the carbon permit price to approach zero, as has occurred in the EU’s Emissions Trading Scheme.

Now, what happens if some people “virtuously” reduce emissions for altruistic reasons? Would they simply be making room under the cap for more emissions by someone else? Prof. James Kahn at Washington & Lee University examined a similar issue: the ramifications of hypothetical new low-carbon energy technology under a cap. Using standard tools of economic analysis such as demand curves, Kahn found that the reduction in allowance prices due to the new technology would stimulate new demand that would exactly cancel out the reduction in emissions. Extrapolating from Kahn, it appears reasonable to expect that altruistic reductions under a carbon cap would similarly reduce allowance prices and create a price signal to consume more, thus canceling out those reductions.

This perverse consequence of a carbon cap makes perfect sense, unfortunately. Consider a commuter who, independent of any price signal or federal legislation, resolves to give up solo car commuting for a carpool. Under a cap system, this “exogenous” reduction in demand for carbon emitting will lead to a slightly lower emission permit price — thus stimulating some additional use of fossil fuels elsewhere. The incremental usage might be a reciprocal departure from a carpool, or cranking up the heat, or a return to buying bottled water rather than refilling at the tap … or any of a thousand other ways to burn carbon. The result, in the end, will be the same: virtue in one arena will be offset elsewhere, due to the price-equilibrium-seeking mechanism of the cap.

This perverse consequence of a carbon cap makes perfect sense, unfortunately. Consider a commuter who, independent of any price signal or federal legislation, resolves to give up solo car commuting for a carpool. Under a cap system, this “exogenous” reduction in demand for carbon emitting will lead to a slightly lower emission permit price — thus stimulating some additional use of fossil fuels elsewhere. The incremental usage might be a reciprocal departure from a carpool, or cranking up the heat, or a return to buying bottled water rather than refilling at the tap … or any of a thousand other ways to burn carbon. The result, in the end, will be the same: virtue in one arena will be offset elsewhere, due to the price-equilibrium-seeking mechanism of the cap.

It gets worse: ACESA includes both a cap and a “renewable electricity standard” (RES) which mandates that electric utilities buy a gradually-increasing fraction of their energy from renewable sources. Resources for the Future studied this same policy combination in Germany. Its finding: Germany’s combination of an RES with a cap caused an increase in the use of coal to generate electricity, as the growth in renewable-energy output created room under the cap for more coal-fired generation elsewhere. In effect, the renewables displaced natural gas-generated electricity instead of coal because gas was more costly, even with coal’s much (roughly 80%) higher carbon content and allowance cost. (This perverse incentive would disappear if allowance prices rose to a level making electricity generation from coal more costly than natural gas.)

To summarize, a carbon cap would tend to cancel out emissions reductions resulting from personal choices and from new technologies. Virtuous conservation and new technologies would reduce allowance prices, stimulating more consumption by others. And, by combining renewable electricity standards with a cap, ACESA would create another perverse incentive because shifting electricity generation to renewables tends to make more room under a cap for coal emissions.

A carbon tax, in contrast, would be free of such “canceling out” mechanisms. Indeed, if anything, “my” tax-induced conservation would tend to encourage “yours” by helping move societal norms away from consumption. And a gradually increasing carbon tax would obviate the need for renewable electricity standards by increasing the cost of high-carbon fuels and stimulating demand for low-carbon alternatives.

Finally, a carbon tax would sidestep what is likely to be cap-and-trade’s biggest “toxic” side effect: a volatile new carbon market that would benefit only speculators and could crash world financial markets again.

Photo: Flickr / megabooboo.

The Cap-and-Trade Corruption

The Cap-and-Trade Corruption (Fox News – Bill O’Reilly Talking Points)

Senate Can Strengthen Climate Legislation By Reducing Corporate Welfare and Boosting True Consumer Relief

Senate Can Strengthen Climate Legislation By Reducing Corporate Welfare and Boosting True Consumer Relief (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities)

Krugman: China's Empire of Carbon

Krugman: China’s Empire of Carbon (NYT)

The Just Framework for Climate

The Just Framework for Climate (Down to Earth [India])

Think-Tank Gives Thumbs-Up to "Dividending" Carbon Revenues

Dividend? Yes.

Payroll tax-shift? No.

EITC tax-shift? Yes.

Energy-efficiency? Hmm, tell me more.

These are the bottom lines on carbon "revenue treatment," as we read them, of Resources for the Future’s impressive new report, The Incidence of U.S. Climate Policy. Released late last week, the report concludes that distributing carbon permit or tax revenues equally among U.S. residents would be income-progressive, whereas using the revenues to reduce payroll or income taxes would widen the already yawning income gap between rich and poor.

These findings appear just as serious attention is beginning to be paid in carbon-pricing circles to the disposition of the enormous revenues that would be raised under either a hefty carbon tax or a stringent carbon cap-and-trade system. Tomorrow, Sept. 16, the Energy and Environmental Study Institute and Clean Air – Cool Planet are co-hosting a Capitol Hill briefing on Climate Change Legislation and Revenue Recycling, while on Thursday Sept. 18 the House Ways & Means Committee is convening a Hearing on Policy Options to Prevent Climate Change focusing on revenue treatment.

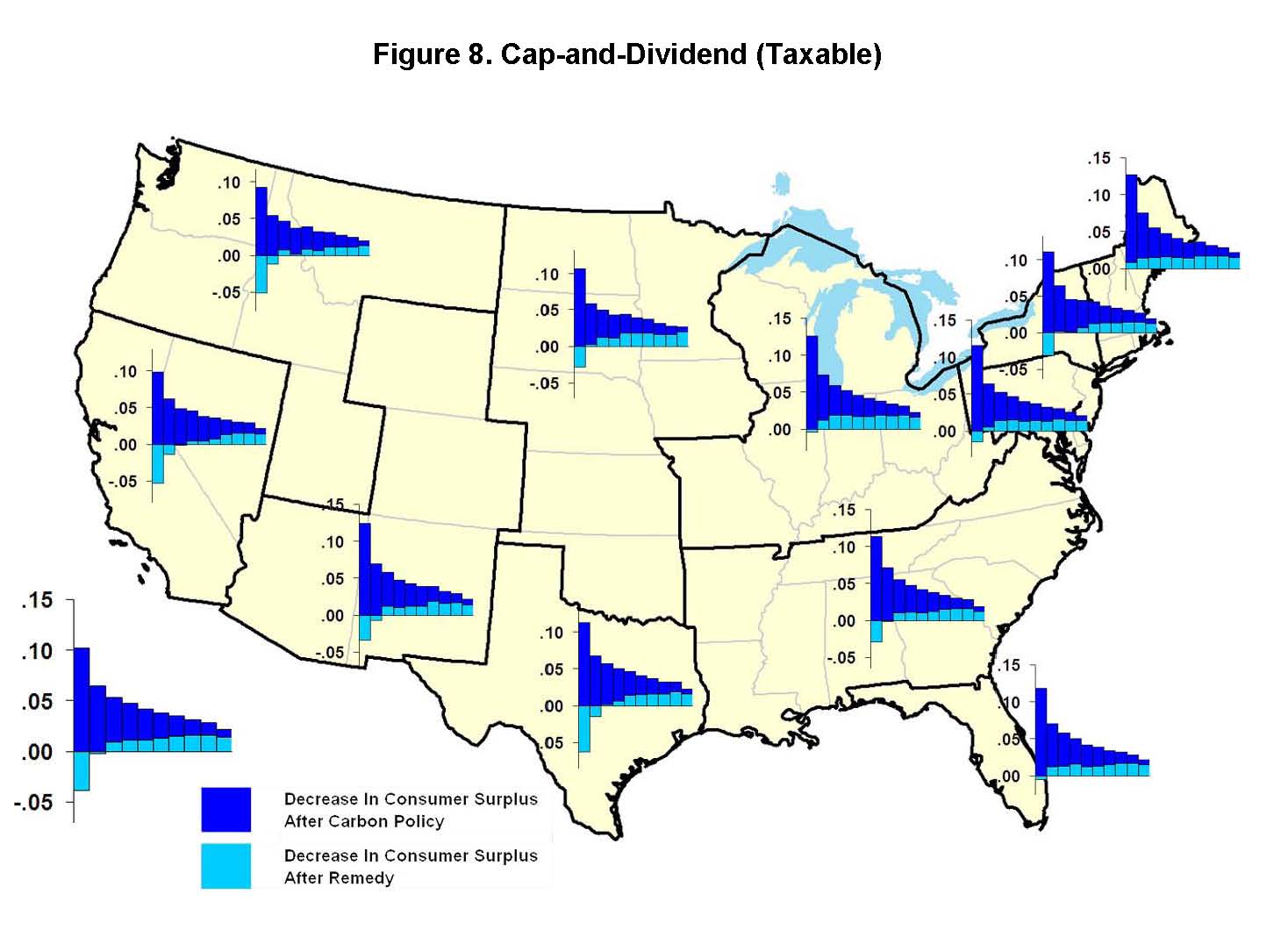

The RFF report evaluated the effects of a CO2 cap-and-trade program on households in each of 11 regions of the country and sorted into annual income deciles, i.e., 10 income-percentage groupings. (The light blue bars in the chart at right denote net costs for each decile from poorest to richest after the revenue-dividend "remedy," with downward-pointing bars indicating net gains; these incidence findings for cap-and-dividend should apply about equally for a carbon tax-and-dividend.) Using the Modified Suits Index, or MSI (a variant of the better-known Gini coefficient for measuring income inequality), the report calculates an MSI of plus 0.15 for the cap-and-dividend approach championed by social entrepreneur Peter Barnes. Since an MSI of zero indicates income-neutrality, while minus one and plus one denote perfect regressivity (all taxes fall on the poorest decile) and progressivity (only the wealthiest are taxed), respectively, the plus 0.15 rating indicates that cap-and-dividend would be moderately progressive. And indeed, the RFF analysis finds that cap-and-dividend would produce a significant gain in "consumer surplus" (overall utility) for households in the lowest income decile, but a loss for most higher-income families.

The RFF report evaluated the effects of a CO2 cap-and-trade program on households in each of 11 regions of the country and sorted into annual income deciles, i.e., 10 income-percentage groupings. (The light blue bars in the chart at right denote net costs for each decile from poorest to richest after the revenue-dividend "remedy," with downward-pointing bars indicating net gains; these incidence findings for cap-and-dividend should apply about equally for a carbon tax-and-dividend.) Using the Modified Suits Index, or MSI (a variant of the better-known Gini coefficient for measuring income inequality), the report calculates an MSI of plus 0.15 for the cap-and-dividend approach championed by social entrepreneur Peter Barnes. Since an MSI of zero indicates income-neutrality, while minus one and plus one denote perfect regressivity (all taxes fall on the poorest decile) and progressivity (only the wealthiest are taxed), respectively, the plus 0.15 rating indicates that cap-and-dividend would be moderately progressive. And indeed, the RFF analysis finds that cap-and-dividend would produce a significant gain in "consumer surplus" (overall utility) for households in the lowest income decile, but a loss for most higher-income families.

Conversely, a cap-and-trade with much of the revenue applied to reducing payroll taxes, as long urged by Al Gore, has an expected Modified Suits Index of minus 0.33, indicating considerable income-regressivity. Indeed, that figure is more extreme than the minus 0.18 value estimated for cap-and-trade before considering revenue uses, strongly suggesting that applying carbon revenues to reduce payroll taxes is a non-starter so far as protecting poor families is concerned. Using carbon revenues to increase the Earned Income Tax Credit is progressive, however, with an expected MSI of plus 0.23.

Intriguingly, RFF holds out high hopes for investing carbon revenues in energy-efficiency programs. According to the report, investing in "EE" would yield around the same "progressive" outcome (an MSI of plus 0.16) as cap-and-dividend, but with larger emissions reductions. Though the authors note that "There are important institutional challenges to achieving gains from end-use efficiency investments," they add that "our modeling suggests that if these challenges can be overcome such a policy might have important distributional benefits."

The RFF geographical analysis is also encouraging, generally finding lesser interregional differences than are often supposed — largely because regions with high carbon consumption in one sector, such as driving, tend to have offsetting lower carbon usage in other sectors like home heating.

We encourage visitors to this Web site to comment with their own observations on the RFF report and the issues it addresses.

Image courtesy of Resources for the Future.