This post first appeared in The Washington Spectator, which posted it yesterday, Feb. 19. We’ve edited it slightly: swapping in a more finely-grained pie chart of trips to the zone by mode, adding a Hochul-vs-Trump graphic, and substituting excerpts from and a link to Gov. Hochul’s Grand Central Station press conference in place of an earlier quote from Reinvent Albany head John Kaehny. The remaining content is the same.

— C.K., Feb. 20, 2024

So much winning. Unjammed bridges and tunnels. Speedier deliveries. On-time buses. Calmer, more inviting streets. Fewer traffic crashes. Repairmen getting to more jobs.

Not Donald Trump’s kind of winning, however. Trump didn’t invent congestion pricing. A Nobel economist — a Canadian, at that — worked out the theory 60 years ago, and a ragtag crew of transit lovers, car inquisitors and dyed-in-the-wool urbanists spent decades importuning New York’s political establishment to put it into practice.

The president had nothing to do with the toll plan. In fact, everything about it screams woke — or does to troglodytes too blinkered to see that congestion pricing’s biggest beneficiaries are motorists, who daily reap substantial dividends in saved travel time.

So it came as no surprise that today Trump’s transportation secretary Sean Duffy told NY Gov. Kathy Hochul that the president intends to rescind federal approvals and to terminate the toll program, which went into effect in early January.

Fortunately, officials at the state-chartered Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which operates the city’s buses, subways and major bridges, and was invested half-a-dozen years ago with legal authority to administer the congestion pricing program, were ready. Mere minutes after Duffy’s announcement, the MTA filed a 51-page complaint in federal court charging Duffy, U.S. DOT and the Federal Highway Administration with usurping their statutory authority and seeking to bar them from interfering with the tolls.

Ozempic for Cities

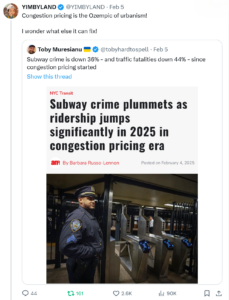

“Am I tripping?,” shock jock Kai Cenat asked on Hot-97 last month. “Congestion pricing might actually be working.” Self-styled housing advocate YIMBYLAND pointed to plummeting subway crime and dubbed congestion pricing “the Ozempic of urbanism,” musing, “I wonder what else it can fix.”

Congestion pricing’s success at cutting traffic is winning converts.

The answer is: quite a lot. The unmistakable takeaway thus far is that just a few fewer cars goes a long way. The drop in the number of vehicles driven into the toll zone is probably 10 percent tops (conclusive data isn’t out yet). But it feels like more. In the papers and on TV, drivers are reporting less time stuck in their cars. In a recent poll, habitual car commuters to Manhattan strongly backed congestion pricing.

The “stick” that has dialed down traffic’s manifold negatives is actually fairly modest — a $9 toll to drive into Manhattan south of 60th Street. Compare that to my calculation that a median car commute to and from the congestion zone slows down the other cars, trucks and buses in its gravitational field by an aggregate of minutes and seconds that equate to $100 worth of lost time. As the toll “carrot” kicks in, in the form of $15 billion worth of transit improvements that the toll revenues will bond, subway travel will get better and safer, helping shrink car use even more.

To be sure, traffic will rebound somewhat as drivers feel the allure of less-clogged roads. But unlike traffic cops or synchronous traffic lights or other traffic-taming nostrums perennially attempted in New York and other U.S. cities, congestion pricing will yield a durable drop in traffic. Sure, call it a miracle. I have. But the eased traffic is the predictable product of pricing “congestion causation” into car trips that collectively create traffic jams.

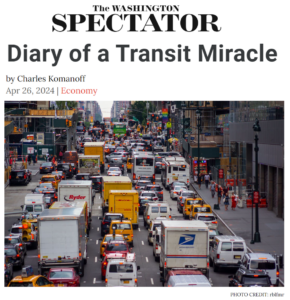

The Serpentine Road to Jan. 5

What looks straightforward in print was, in practice, anything but. In Diary of a Transit Miracle, published in The Washington Spectator last April, I traced the 50-year effort to define, scope, build support for, and legislate New York congestion pricing. The miracle, I wrote, was three-fold: “Winners will far outnumber losers; New York will be made healthier, calmer and more prosperous; and that this salutary measure is happening at all, after a half-century of setbacks.”

Soon enough, the triumphant odyssey was torpedoed in the bow. On June 5, Gov. Kathy Hochul, whose office has authority over the MTA and, thus, over congestion pricing, peremptorily and indefinitely “paused” its June 30 start — a perfidy I dissected in Hochul Murder Mystery. The outbreak of pro-congestion pricing support would persist, I predicted, returning the governor to the fold — as happened in November, after the election. Congestion pricing would go into effect on Jan. 5, though scaled back from the June 30 rates. The intended $15 peak toll was lowered to $9, with truck tolls and taxi and Uber surcharges reduced by 40 percent as well.

Congestion pricing supporters at Lexington Ave. and 60th Street, 12:03 a.m. Jan. 5, 2025. I’m at center, foreground, holding yellow sign and chatting with journalist-author Christopher Ketcham. Tall man smiling at right is Rit Aggarwala, who led Mayor Bloomberg’s 2007-2008 bid to enact congestion pricing and now heads the city’s Dept of Environmental Protection. Photo: Sproule Love.

Even diminished, congestion pricing promised much for New York — especially if Hochul or a successor adhered to her pledge to raise the toll to $12 in 2028 and, in 2031, to the full $15. Toll supporters gladly took the win. As midnight approached on Jan. 4, we thronged Lexington Avenue and 60th Street, braving the midnight cold to count down the final seconds of life without congestion pricing.

We were festive and appreciative. “NY ♥s drivers who pay,” read my sign. “Thank you for paying the toll,” said another. “You’re making history!,” proclaimed a third. No one asked if “you” denoted the crowd, or the drivers whizzing by, or our fair city. For a bright, shining hour, it was everyone.

Why Trump Wants to Eradicate Congestion Pricing

Once upon a time, a wannabe developer looking to make a mark in Manhattan might have bet on congestion pricing. Wharton might have schooled him that prices beat queues at sorting supply and demand. He might have paid notice in the 1980s as true-life real estate titan Dick Ravitch used his pulpit as MTA honcho to hammer home that a thriving Gotham required functional transit, which in turn required robust new revenue streams. Throughout Mike Bloomberg’s mayoralty, he might have listened as Kathy Wylde, chief of the blue-ribbon business group Partnership for New York City, repeatedly decried region-wide traffic gridlock as a $20 billion a year tax on residents and businesses.

Meanwhile, of course, Donald Trump did none of those things. From time to time he fulminated against congestion pricing, though more as a nuisance like, say, water-saving flush toilets. As president he escalated his rhetoric. In a Feb. 8 interview with the New York Post, Trump called the tolls “horrible” and “destructive to New York.” Ignoring mounting evidence like January’s big year-on-year uptick in attendance at Broadway shows, he dismissed the reductions in traffic jams, rationalizing that “Traffic is way down because people can’t come into Manhattan and it’s only going to get worse.”

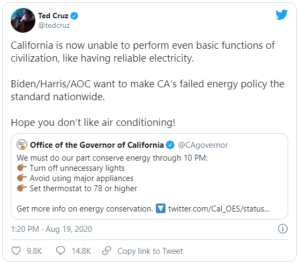

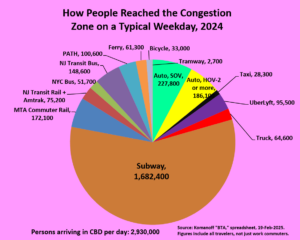

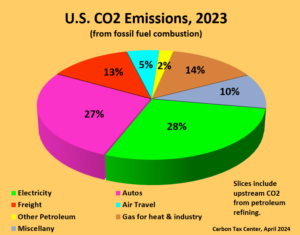

That’s your standard “windshield perspective” at work, oblivious to the reality that barely one-fifth of folks coming to the Manhattan congestion zone arrived in a private vehicle prior to congestion pricing. (See chart.) True enough, a few days after Trump’s Post interview, local news sources reported a rise in Manhattan foot traffic in congestion pricing’s first month compared to the year before.

Pre-tolling, only one-fifth of person-trips to the congestion zone were via private vehicle; among regular work-commuters the share was even smaller.

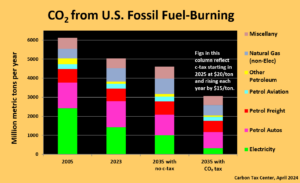

Still, the Trumpian brain gazing at congestion pricing sees not a respite from traffic gridlock but oil barons’ birthright squandered on mass transit and climate. Ironically, the tolls’ direct hit to petroleum and carbon will be relatively modest; by design, congestion pricing applies just to a sliver of city driving.

If congestion pricing had a motto, it would be, “Don’t ban cars, bill them” —a mantra lost on The New York Times, which today wrote> that the tolls “aimed to discourage drivers from entering the congestion zone.” Wrong. Congestion pricing seeks to dissuade a smallish fraction of drivers — 10 to 20 percent — from doing so. The other 80 to 90 percent are meant to keep driving to ensure sufficient toll revenues to bond the promised transit investments.

Subtle truths be damned, congestion tolling is anathema to Trumpworld, where policy considerations are buried under monstrous simplification, crude disinformation, coarse slander and, most often, outright lies. Congestion pricing’s crime is that it elevates the collective interest above individual actions that threaten it. It requires drivers to Manhattan’s teeming center to either change their behavior for the common good of congestion reduction, as Paul Krugman put it recently, or to offset some of the harms from their driving by paying into a government-administered kitty — to be invested in transit betterment that will reducing congestion further.

Krugman conjectured that “hostility to New York” may be the true font of Trump’s antipathy to congestion pricing. “Many people, and Trump in particular,” Krugman wrote, “are committed to the view that [New York] is an urban hellscape. A policy that improves life in the city runs counter to that narrative and inspires visceral opposition. And Trump in particular surely wants to hurt a city that has never supported him.”

A balm for New York, if we can keep it

It’s easy to be gloomy about congestion pricing’s ability to overcome Trump’s enmity. Even if the MTA prevails over Secretary Duffy in federal court — and the Authority appears to have a strong hand — the Trump administration has myriad ways to coerce New York State into ending the program. It could slow Federal Transit Administration reimbursements to the MTA for expenditures already authorized and made. Going forward, Trump could constrict routine federal contracts to rehabilitate and build new transit. The rational choice for the state and MTA might then be to give up the toll program.

Or, Trump could hold that power in reserve as leverage to get New York City and State to fall in line or not make waves on a hundred other fronts. Not selling out congestion pricing requires Gov. Hochul to be steadfast and for Mayor Eric Adams, who began distancing himself from the tolls long before bending his knee to Trump, to leave or lose his mayoralty to a congestion pricing defender.

Hochul, for her part, is off to a rousing start. Addressing congestion pricing supporters at NY’s Grand Central Station yesterday, she said:

At 1:58 pm, President Trump tweeted, ‘Long live the king.’ I am here to say that New York hasn’t labored under a king in 250 years and we are sure as hell not going to start now… We stood up to a king and we won then. In case you do not know New Yorkers, we’re in a fight, we do not back down — not now not ever… I don’t care if you love congestion pricing or hate it, this is an attack on our sovereignty, our independence, from Washington. We are a nation of states. We are not subservient to a king or anyone else from Washington… We will not [let] the commuters of our city and our region [become] roadkill on Donald Trump’s revenge tour against New York.

But to feel the governor’s steely determination to keep congestion pricing, it’s best to hear her. This 20-minute YouTube video of her and MTA chief Janno Lieber leaves no doubt that she is more than ready to go to the mat with Trump. She sounds positively liberated.

“King” Trump vs. Gov. Hochul. Diptych courtesy of Ryder Kessler, Abundance New York.

Of one thing we can be sure: For Hochul to maintain her brave stance will require continued, sustained organizing — more of the grinding work that brought congestion pricing to life in the first place. The old saw about genius being 1 percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration applies here.

In this trilogy’s first installment, I gave pride of place to congestion pricing theorist Bill Vickrey. So did the Times’ “Big City” columnist, in an encomium to the Nobel economist last month that implicitly treated the unceasing toil of congestion pricing’s legions of supporters over the years like so many dust bunnies.

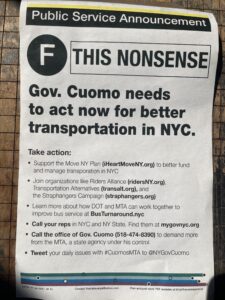

But the Jan. 5 victory belongs not just to Vickrey and Ravitch and Wylde, or to Lieber and his relentless staff, but also to Riders Alliance, Reinvent Albany, Regional Plan Association, the Community Service Society, a revitalized Transportation Alternatives, and scores of allied organizations and associations that together coalesced into a civic force for municipal progress, good governance and improvements in our quality of life. And to the journalists who gave our labors prominence.

These organizations internalized and acted on the twin beliefs that having too many cars hurts cities, and that traffic pricing is indispensable for diminishing the automobile’s stranglehold over transportation budgets and road designs. After Hochul’s congestion pricing “pause” last June, they rose as one to block her ploy to concoct a substitute transit funding source. “We never considered it, not for a minute,” Riders Alliance senior organizer Danna Dennis told me earlier this month. “It was congestion pricing all the way.” Likewise for Liz Krueger, state senator from Manhattan’s east side, who rallied her Albany colleagues to render the governor’s gambit dead on arrival.

The result, on Jan. 5, was an epic breakthrough. For the first time in the USA, driving is being assessed a charge for some of the immense harms it wreaks on urban life. At this writing, 45 days on, the facts on the ground are everything that congestion pricing proponents dreamed of and promised. Every new day that dawns with the tolls intact puts the lie to the claims of Trump’s minions that the program is hurting New York. Sure, like Ozempic hurts the chronically obese.

It can feel unfair to have to keep on defending a program that has the force of law and is working wonders. But we must and we will.

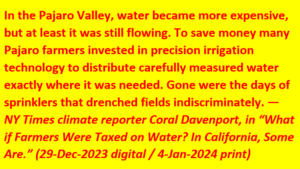

Just as importantly, the growers receive a potent incentive to use available water supplies more efficiently. “Gone were the days of sprinklers that drenched fields indiscriminately,” Davenport writes. “To save money, many Pajaro farmers invested in precision irrigation technology to distribute carefully measured water exactly where it was needed.” (See text box.) Though the article doesn’t mention it, these investments by dozens of individual growers might not have materialized had not all growers been subject to the same incentives to conserve as well.

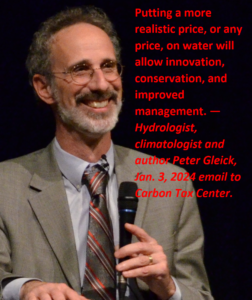

Just as importantly, the growers receive a potent incentive to use available water supplies more efficiently. “Gone were the days of sprinklers that drenched fields indiscriminately,” Davenport writes. “To save money, many Pajaro farmers invested in precision irrigation technology to distribute carefully measured water exactly where it was needed.” (See text box.) Though the article doesn’t mention it, these investments by dozens of individual growers might not have materialized had not all growers been subject to the same incentives to conserve as well. After reading Davenport’s article I reached out to hydrologist, climatologist and water sustainability expert Peter Gleick, whose latest book,

After reading Davenport’s article I reached out to hydrologist, climatologist and water sustainability expert Peter Gleick, whose latest book,

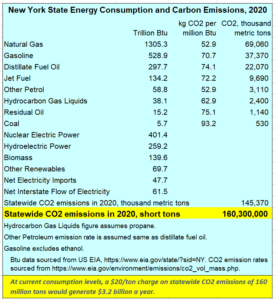

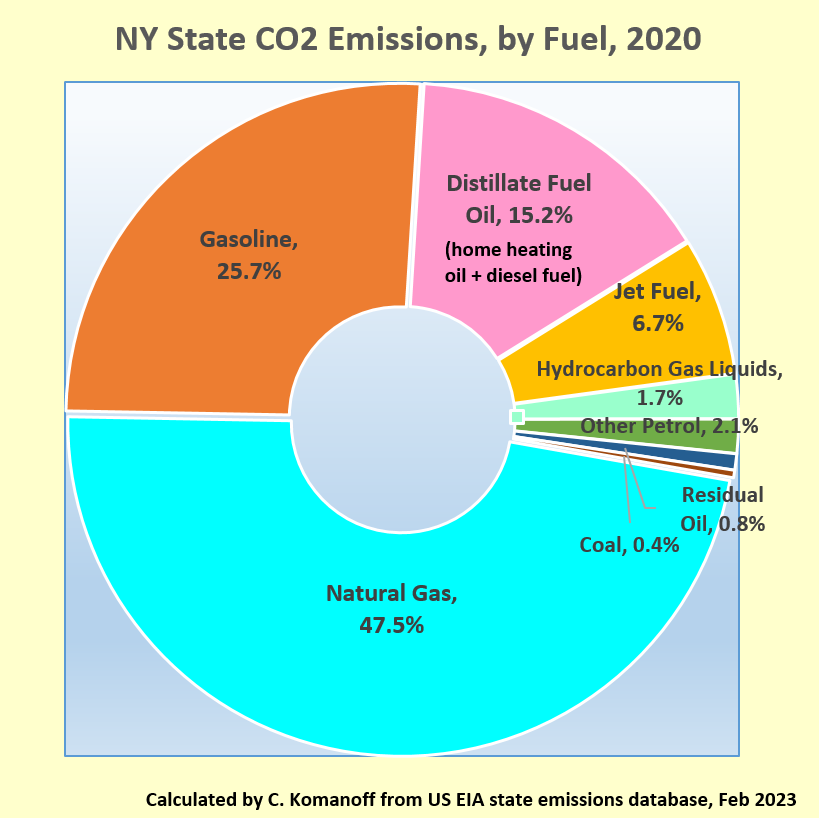

That huge sigh of relief from New York City mass transit advocates last weekend was for the state budget handshake to tack more than a billion additional dollars a year onto a key MTA funding stream, the Payroll Mobility Tax. According to both my calculations and

That huge sigh of relief from New York City mass transit advocates last weekend was for the state budget handshake to tack more than a billion additional dollars a year onto a key MTA funding stream, the Payroll Mobility Tax. According to both my calculations and  Dedicating a third of those proceeds to the MTA would add a billion dollars to the authority’s annual revenue. Other slices of the revenue could cure deficits at smaller transit systems around the state.

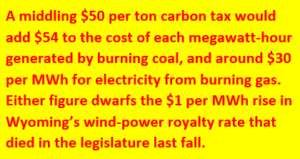

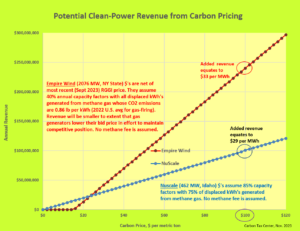

Dedicating a third of those proceeds to the MTA would add a billion dollars to the authority’s annual revenue. Other slices of the revenue could cure deficits at smaller transit systems around the state. RGGI currently charges electricity producers around $14 for each ton of CO2 their generators emit. This levy is generating

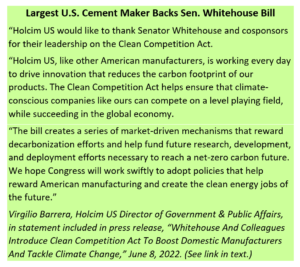

RGGI currently charges electricity producers around $14 for each ton of CO2 their generators emit. This levy is generating  No federal legislation with a price on carbon has advanced to a floor vote since the “Waxman-Markey”

No federal legislation with a price on carbon has advanced to a floor vote since the “Waxman-Markey”  Whitehouse sees his bill as a way to use U.S. trade policy to drive climate action. He also views its potential to boost U.S. industrial competitiveness as a way to attract bipartisan support. Holcim U.S., whose parent company, Lafarge Holcim, is America’s largest cement manufacturer,

Whitehouse sees his bill as a way to use U.S. trade policy to drive climate action. He also views its potential to boost U.S. industrial competitiveness as a way to attract bipartisan support. Holcim U.S., whose parent company, Lafarge Holcim, is America’s largest cement manufacturer,