Note: A new (March 2021) CTC page, Carbon Pricing and Environmental Justice, summarizes this post and its Sept. 2020 predecessor, Environmental Justice, Borne Aloft by Carbon Pricing, and embeds them in a larger narrative about the environmental justice movement’s increasing turn against carbon pricing.

Mary Nichols’ candidacy to lead the US Environmental Protection Agency is over. Not so, the need to grapple with the profound mistrust of carbon pricing felt by many advocates for environmental justice.

Nichols, long-time California clean-air chief, was considered “a lock” to head the EPA, according to the New York Times, until 70 environmental justice and allied groups sent a strongly worded letter, excerpted at left, to the Biden-Harris transition team opposing her nomination. The new administration’s selection of North Carolina environmental quality secretary Michael Regan for the position was announced last week.

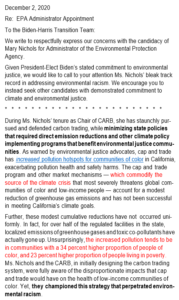

Excerpt from 70 groups’ Dec. 2 letter. Bold is from original, red is CTC’s emphasis. The link is to the Cushing analysis discussed in this post. Additional text criticizing cap-and-trade isn’t shown here.

Signatories (download the letter here, pdf) included national organizations Friends of the Earth, Greenpeace, Food & Water Watch and Oil Change International, along with dozens of California groups and the umbrella California Environmental Justice Alliance.

A principal charge in the letter, and the one singled out by the Times and in other media accounts, was a claim that the carbon cap-and-trade program overseen by Nichols and the California Air Resources Board “perpetrates environmental racism [by] increas[ing] pollution hotspots for communities of color in California.”

That charge may be seen as a culmination of the deep suspicion with which many environmental justice advocates regard pollution taxes or cap-and-trade schemes (the two are often termed “market measures”) intended to cut carbon emissions.

I did my own grappling with this matter in a lengthy post here in September. I noted inter alia that “many activists recoil from carbon pricing’s implicit acquiescence to capitalist means of exchange that [appear to] commodify pollution” — language similar to the EJ letter’s charge that “market mechanisms … commodify the source of the climate crisis.”

Ironically, those who, like me, train an economic lens on the climate crisis regard the failure to price carbon emissions as a source of the climate crisis. And not just economists but the entire environmental community is united in demanding elimination of fossil fuel subsidies. Yet the ability to dump carbon pollution into the atmosphere for free is the biggest subsidy of all, and carbon taxes (or “charges”) uniquely diminish that subsidy.

Nevertheless, the sharper irony, addressed here, is that the cap-and-trade program that is being vilified for perpetrating environmental inequities appears in practice to be diminishing them.

Environmental Inequity and Pollution Hotspots

As recently as a decade ago, ground-level concentrations of deadly carbon “co-pollutants” — toxic particles and gaseous oxides — issued from industrial smokestacks in California were three to four times higher in disadvantaged communities than in more affluent and predominantly white locales. That result was derived in an analysis published earlier this year by two U-C Santa Barbara economists, ratifying what environmental justice campaigners from these communities have always understood.

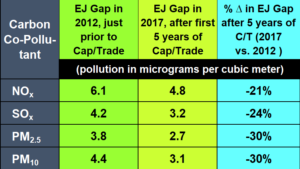

Truncated version of table from my Sept. 28 post. EJ Gap is difference in ambient air pollution between CA-codified “disadvantaged” zip codes and other locales. Blue column shows narrowing of gap.

Compounding this long-standing health assault, an early cap-and-trade program meant to curb smog in California (called Reclaim) was riven with escape clauses that, it is said, emboldened increases in pollution dumping onto minority communities from an enormous oil refinery — the state’s second largest — in Richmond, near San Francisco. The conviction was soon born that pricing of pollution, whether auctioned to polluters as tradeable emission permits (cap-and-trade) or charged directly (via pollution taxes), could never mitigate pollution inequities afflicting historically-burdened communities of color.

This belief grew and intensified across California, fueled by intersecting political and social currents and by research suggesting that a newer, more ambitious and less porous statewide carbon cap-and-trade program legislated in 2006 and put in place in 2013 by the California Air Resources Board was likewise concentrating emissions in minority communities. (A 2019 paper, California Climate Policies Serving Climate Justice, by Univ. of San Francisco Law Professor Alice Kaswan, is a useful guide to the state’s many laws addressing carbon emissions and environmental injustice.)

Must carbon pricing worsen hotspots?

The specter of “hotspots” is paramount in the Dec. 2 EJ letter and prominent in environmental justice expressions on pollution pricing. Yet the idea that polluters respond to charging for pollution by perpetuating or, worse, exacerbating toxic emissions in poor communities runs counter to almost everything we know (or believe we know) about how polluting enterprises actually operate.

A carbon tax, by its nature, exacts a cost for every missed opportunity to reduce carbon emissions. Carbon pricing makes every means — and there are literally billions at hand — of reducing carbon emissions more profitable, which is why devotees of carbon taxes find them so enticing.

The price incentive, we believe, gives individuals and especially companies new cost-effective means to pare their use of carbon fuels. (The same is true for carbon cap-and-trade programs, although there the cost is paid, somewhat indirectly, via the polluting company’s purchase of emission permits, and the price signal is found in the carbon-permit market.) Accordingly, a company that deliberately perpetuated toxic hot spots in disadvantaged communities would weaken its bottom line.

Consider an oil company that operates 10 refineries — 5 in minority communities, 5 in white locales. Under a carbon price, every new piece of equipment or procedure that reduces carbon emissions at any of the 10 reduces the company’s carbon tax tab (or its cap-and-trade expenses).

All 10 refineries will almost certainly undergo some change to lower their emissions. Logistical considerations or racial favoritism might conceivably lead the company to concentrate more of its reduction effort at its 5 white sites. But it strains credulity to posit that the minority sites will take on more emissions on account of the carbon price.

The reason? Carbon pricing is a unitary policy that applies equally to all emissions. Charging for emissions creates opportunities to cut emissions everywhere, simultaneously. The choice presented to headquarters isn’t to pit potential reductions from Refineries 1-5 against reductions from Refineries 6-10, but to max out on the new cost-cutting opportunities that the carbon price presents at Refineries 1 through 10 .

This schematic suggests that even community-neutral pricing policies — ones that lower total emissions without regard to where — will benefit disadvantaged communities in health terms. That is true even if the relative bias of disproportionate burdens on those communities isn’t specifically targeted, whether in the pricing design or in the use of the carbon-pricing revenues.

Keep in mind that the refineries or other large emitters that are most cost-effective to upgrade or downsize because of the carbon price will be those with the oldest, most-polluting equipment. To the extent that these are in poorer communities — a syndrome that the environmental justice movement has documented for decades — the emission reductions will be concentrated there as well.

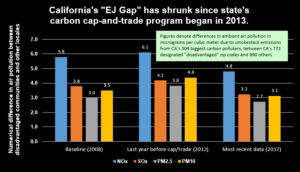

Graphic from my Sept. 28 post illustrates the narrowing in California’s “EJ” gap due to the state’s cap-and-trade program.

There is also the mathematical fact that equal percentage reductions across the board will bring the greatest absolute emission reductions where the baseline emissions are highest. If polluters are spewing 200 tons of pollution on your community but only 100 tons on mine, a 25% reduction everywhere will cut emissions in your back yard by 50 tons, vs. 25 tons in mine.

For the inequitable historic differential in pollution exposures to widen, there would have to be grossly lesser emission percentage reductions in minority areas. In the example above, the decrease in emissions in those areas would have to be held to just 25% while emissions elsewhere fell 50% or more.

A few such examples can probably be found in California, among the 300-plus emitters large enough to be covered by the state’s carbon cap-and-trade program. But so long as the overall cap is tightened each year while “offsets” and other loopholes are kept to a minimum, any increases will be far outweighed by reductions in other low-income communities of color.

A Startling Finding about California’s Carbon Cap-and-Trade Program

In early August, I learned of a new academic paper that, in its elegance and reach, appeared capable of singlehandedly untethering carbon pricing from the charge of environmental injustice. The paper is the one mentioned up front that found that just a decade ago, as a baseline, California’s disadvantaged communities suffered from far larger concentrations of carbon “co-pollutants” from industrial smokestacks, compared to whiter and more prosperous locales.

The person who collegially notified me of the paper was Lara Cushing, an epidemiologist (MA) and energy policy specialist (PhD). It was Prof. Cushing’s team whose research was cited in the letter to the Biden-Harris team charging that California’s carbon cap-and-trade program “perpetrates environmental racism.”

During the rest of August and most of September I pored over the academic paper, which was titled, “Do Environmental Markets Cause Environmental Injustice? Evidence from California’s Carbon Market.” I corresponded with its authors, members of U-C Santa Barbara’s economics department: PhD candidate Danae Hernandez-Cortes and Associate Prof. Kyle C. Meng. Their paper was complex and bursting with implications, and I wanted to be certain I understood it fully before writing it up. I circulated a draft story to a few environment-oriented outlets for publication or a news exclusive, eventually posting it myself to the Carbon Tax Center website on Sept. 28 as Environmental Justice, Borne Aloft by Carbon Pricing.

Hernandez-Cortes and Meng’s key finding, I explained, was this: From 2012 to 2017, the pollution disparity between disadvantaged and other communities in California fell an estimated 30 percent for particulates, 21 percent for nitrogen oxides and 24 percent for sulfur oxides. Moreover, the 21-30 percent drops in the state’s “EJ gap,” as they termed the disparity, was not merely concurrent with the cap-and-trade program, which CARB put into effect in 2013; it was “due to the policy” itself, according to the authors.

This finding differed diametrically from the conclusions of Prof. Cushing and her colleagues, and I was obliged to explain why. The account from my post is shown in the sidebar and summarized below:

- To weed out macroeconomic and other extraneous factors and discern the cap-and-trade program’s specific effects on its “covered” facilities, Hernandez-Cortes and Meng included a comparison group of unregulated California emitters.

- Hernandez-Cortes and Meng traced the atmospheric paths taken by the pollutants once they left the smokestacks, via modeling, rather than assuming they landed in narrow bands nearby.

- Hernandez-Cortes and Meng based their before-and-after calculations on each facility’s actual emissions — a richer and more accurate approach than the earlier work’s up-or-down formulation.

Reactions to the Hernandez-Cortes – Meng Findings

My post highlighting the Hernandez-Cortes – Meng findings drew little comment (none from the environmental justice campaigners to whom I reached out) and very little press. The paper’s two mentions in the green press — in an October article in Grist, Cap and Trade-Offs, and in a November story in Yes! magazine, Can California’s Cap and Trade Actually Address Environmental Justice? — were cursory and largely dismissive.

For example, the Yes! article said that the 20% to 30% narrowing of the EJ gap applied only “in the areas where facilities were covered by the program,” whereas Hernandez-Cortes and Meng actually calculated the reductions across all of California’s 1,712 populated zip codes. The Grist story obfuscated Hernandez-Cortes and Meng’s statistically significant modeling of smokestack dispersions as reflecting only “a spread of outcomes of various likelihoods” — whatever that means.

One could almost intuit a wish to cling to the Cushing team’s negative conclusion about cap-and-trade’s outcomes, and thus to downplay Hernandez-Cortes and Meng’s ingenious analysis that had apparently upended it.

Finally, in late November, a substantive critique of the Hernandez-Cortes – Meng analysis appeared. It was posted by Danny Cullenward, a lecturer and affiliate fellow at Stanford Law School, and Katie Valenzuela, who formerly was policy and political director for the California Environmental Justice Alliance and co-chair of California’s AB 32 Environmental Justice Advisory Committee (AB 32 is the state’s 2006 umbrella climate law).

Yet the Cullenward-Valenzuela criticisms of Hernandez-Cortes – Meng appear to point to imperfections, not fatal flaws.

To wit: Hernandez-Cortes and Meng employed zip codes and not finer-grained census codes to compare EJ neighborhoods with other locales. Hernandez-Cortes – Meng drew smokestack data from the state’s 35 different regional air districts that, they say, “use 35 different methods for data collection.” Hernandez-Cortes and Meng didn’t adjust for possible confounding effects from California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard, a companion climate measure that took effect during the period covered in their cap-and-trade analysis.

Notably, however, neither Cullenward-Valenzuela nor anyone else writing from an environmental justice perspective criticized the Cushing team’s analysis — the one bolstering the belief that the cap-and-trade program has deepened environmental inequities — for these same failings, let alone its more consequential shortcomings I enumerated in the preceding section. Nor did Cullenward and Valenzuela attempt to quantify how much, if at all, remedying the asserted shortcomings in the Hernandez-Cortes and Meng paper would weaken their findings.

Perhaps the weightiest criticism of Hernandez-Cortes – Meng from Cullenward and Valenzuela is their last, under the heading, “The question is not cap-and-trade versus nothing”:

If California had chosen a path of more prescriptive, direct emissions reductions … we would likely be seeing far more emissions reductions … and far more improvements for environmental justice communities than we’re seeing under the cap-and-trade program today. To say [the cap-and-trade program is] better than nothing ignores the fact that adopting a weak cap-and-trade program has led to prolonged and higher emissions in environmental justice communities than if California had adopted a stringent carbon pricing policy or relied instead on non-market mechanisms that would have been targeted at the pollution reductions our communities need.

That claim may well be true. It certainly resonates with me, an advocate since the late 1980s of straight-up carbon taxing rather than oblique and often loophole-plagued cap-and-trade approaches. But that’s not the question that Hernandez-Cortes and Meng tackled in their study, which was: On a statewide basis, has California’s cap-and-trade program widened or narrowed environmental inequities?

Though California EJ advocates insist that the cap-and-trade program has widened environmental inequities, no one has effectively rebutted the evidence marshaled by Hernandez-Cortes and Meng that it has actually narrowed them.

Possible Trouble Ahead

The scant attention accorded the Hernandez-Cortes – Meng paper has largely sidelined its meticulous and virtuosic treatment of the impact of California’s cap-and-trade program on environmental inequities. A result has been to let stand the accusation that the program’s sponsoring agency, the California Air Resources Board, has “perpetrated environmental racism.”

My concern here is not that that charge helped block CARB’s Mary Nichols from heading EPA, but with the possibility that its uncritical acceptance may impact national environmental and climate policies going forward.

The idea that carbon pricing cannot serve environmental justice may have been justified by systemic oppression, and it dovetails nicely with certain critiques of capitalism as being a willing handmaiden of inequity. But in its largest empirical test to date in the United States, that proposition has been shown highly questionable. Now, judging by its impact on Nichols, it threatens to block carbon pricing measures from consideration by the incoming Biden administration.

Getting meaningful climate legislation through a divided Congress will be difficult under any circumstances. The temptation will now be strong to jettison measures that might be opposed by advocates for racial justice and others on the left. Another New York Times story this month, this one showcasing president-elect Biden’s choices of Janet Yellen and Brian Deese for Treasury secretary and National Economic Council director, noted that carbon pricing “is fiercely opposed by both conservatives and some liberal groups.”

Carbon pricing, whether rendered through tradeable emission permits or straight up via carbon taxes, faces hurdles galore. Saddling it with unfounded criticisms, notwithstanding their deep wellsprings, appears more likely to compound environmental injustice rather than help overcome it.