The campaign to combat climate change by inducing pension funds, universities and other prominent fiduciaries to dump their fossil-fuel holdings has failed. Ten years into the divestment project, it’s time to move on.

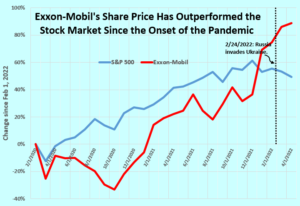

Divestment campaigning doesn’t seem to have damaged Exxon’s share price since 2020.

When the writer and climate activist Bill McKibben kicked off the campaign in a July 2012 Rolling Stone article, Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math, the rationale was three-fold: (1) dry up capital and make it harder for the fossil fuel industry to create new mines, wells, pipelines and terminals; (2) weaken the industry’s social and political standing so it couldn’t easily block pro-climate policy; and (3) by hanging a “Dump Me” sign around Big Oil, amp up climate organizing. Not for nothing did McKibben subtitle his Rolling Stone article, “Make clear who the real enemy is.” It was Exxon and its brethren.

How’s it going, ten years on? Not well. The clearest indication is Exxon-Mobil stock’s new-found attractiveness to investors. From Feb. 1, 2020 to Feb. 1, 2022, a two-year period that predates Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and brackets the Covid-19 pandemic, Exxon’s stock price climbed 75 percent, outpacing the 55 percent rise in the S&P 500 index.

While non-U.S. oil giants Saudi Aramco and BP have appreciated less than the S&P benchmark, the #2 and #3 U.S. oil companies, Marathon Oil and Valero Energy, have matched Exxon’s faster-than-average share price rise. Unsurprisingly, Exxon’s market-beating performance accelerated since Feb. 1, as the oil industry reaps the fruit of high prices without yet suffering much contraction in demand.

It is true that Exxon and other oil majors under-performed the market from 2012 to 2020. So why are oil stocks now so buoyant? The answer lies in robust demand for petroleum products, both in the U.S. (about a fifth of world usage, with half of that in motor fuels) and globally. Until Russia attacked Ukraine, disrupting trade and dampening near-term economic expectations, world petroleum consumption this year was headed to near-record levels.

Is it, though?

More importantly, considering that stock prices essentially embody investors’ expectations of future earnings streams, the lords of capital are betting on the oil and gas business to stay profitable for some time.

Reserves will not stay in the ground, in other words, unless and until consumption shrinks. It ought to be obvious that oil consumption drives production, not the other way around. The same “whack-a-mole” syndrome that made “keep it in the ground” campaigns ineffectual from a climate standpoint (as I lamented in this 2016 post) also afflicts efforts by socially responsible investors to starve capital flows to fossil fuel corporations.

No matter how far divestment penetrates bank boardrooms or Ivy League endowments, a world intent on using fossil fuels can always count on a vast array of wealth holders to finance their resupply.

McKibben admitted as much last fall, shortly after the New York Times reported on meticulous research by the Private Equity Stakeholder Project that found that private equity funds for a decade had been investing $100 billion a year in fossil fuel energy. In an October 2021 Times op-ed (see headline above), he admitted the real purpose of divestment campaigns: to build the climate movement and erode the social and political standing of the fossil fuel industry (what I earlier called aims #2 and #3):

Since most people don’t have oil wells or coal mines in their backyards, divestment is a way to let a lot of people in on the climate fight, because they have a link to a pension fund, mutual fund, endowment or other pot of money. When we began the divestment campaign, our immediate goal was, as we put it, to “take away the social license” of Big Oil. (emphasis added)

This Oct 13, 2021 NY Times story demolished a key rationale for fossil-fuel divestment campaigns.

Movement-building is vital. Eroding the social standing of fossil-fuel extractors and purveyors is overdue. But what happens when divestment activists discover that moving their college or municipal pension fund out of fossil fuels hasn’t visibly changed the material world of energy production and consumption?

In the 2021 op-ed, McKibben added that divestment campaigning “was a vehicle to let people know the essential truth about the fossil fuel industry, which is that its oil, gas and coal reserves held five times as much carbon as scientists said we could safely burn.” That 5-fold incongruity, in fact, was the titular “new math” in his archetypal 2012 Rolling Stone article.

The math is unassailable. McKibben’s new metric demonstrated, ingeniously and incontrovertibly, the incompatibility between oil industry health and planetary health. Yet divestment, as a tactic, hasn’t delivered.

Divestment campaigners have a world of actions and organizing to do instead. For the next six months, though, they need to focus on political action. Electoral action.

Odds be damned, the Democrats have got to hold onto Congress this November. Political commentator Jamelle Bouie reminded us why recently when he was asked why “the Democrats can’t seem to get traction on [climate and other progressive policies] that enjoy broad support”:

In terms of getting policies through Congress, they just don’t have the votes. [But] I think this picture would look very different if there was one more or two more [Democratic] senators. If Cal Cunningham in North Carolina had won [in 2020], if Susan Collins’s opponent in Maine [Susan Gideon] had won, we’d be looking at a very different situation.

Needless to say, a very different situation, of the opposite sort, is what we’ll be looking at if the other, climate-denying, democracy-wrecking party prevails in the midterms. Between now and Tuesday, Nov. 8, not just divestment but probably all climate-focused organizing needs to yield to, or at least be subsumed by, electoral campaigning.

If your state or district is competitive, start electoral organizing now. If not, these resources can plug you in:

- People’s Action has both electoral and non-electoral volunteering.

- Swing Left has local chapters to connect you for phone-calling, post-carding, donating, etc.

- For down-ballot electioneering (which also brings people to vote for up-ballot races): Sister District.

- For Spanish-speaking calling in AZ, connect to Mision por Arizona via Mission for Arizona.

- To donate $$ to grassroots rather than party organizations: Movement Voter Project.

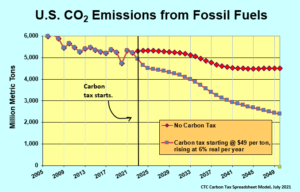

I know that record well. Not long ago, I did a study comparing California’s rate of decarbonizing its economy to the rest of the country’s. I found that from the mid-1970s to 2016, California drove down its use of fossil fuels per unit of economic activity nearly 20 percent faster than the other 49 states. Had those states matched California’s pace, I calculated, the country would now, each year, be eliminating 1,200 megatonnes of CO2, an amount equivalent to the carbon emissions from our entire fleet of passenger cars.

I know that record well. Not long ago, I did a study comparing California’s rate of decarbonizing its economy to the rest of the country’s. I found that from the mid-1970s to 2016, California drove down its use of fossil fuels per unit of economic activity nearly 20 percent faster than the other 49 states. Had those states matched California’s pace, I calculated, the country would now, each year, be eliminating 1,200 megatonnes of CO2, an amount equivalent to the carbon emissions from our entire fleet of passenger cars.

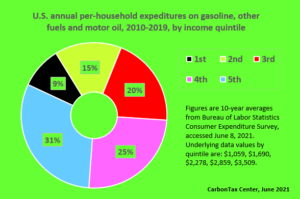

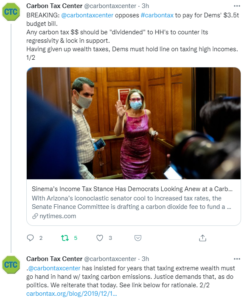

To be clear, CTC has no qualms about raising taxes on the very-affluent as well as the super-rich to make a better society. But raising taxes on the working poor and the beleaguered middle class is another matter entirely. And to the extent that the carbon tax under discussion is meant as a pay-for — literally, to pay for improving America’s physical and social infrastructure — less money will be available for dividends. It’s one thing to set aside a few percent of carbon fee revenues to pay for worker and community transitions, as outspoken climate hawk Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI)

To be clear, CTC has no qualms about raising taxes on the very-affluent as well as the super-rich to make a better society. But raising taxes on the working poor and the beleaguered middle class is another matter entirely. And to the extent that the carbon tax under discussion is meant as a pay-for — literally, to pay for improving America’s physical and social infrastructure — less money will be available for dividends. It’s one thing to set aside a few percent of carbon fee revenues to pay for worker and community transitions, as outspoken climate hawk Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI)

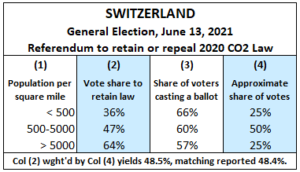

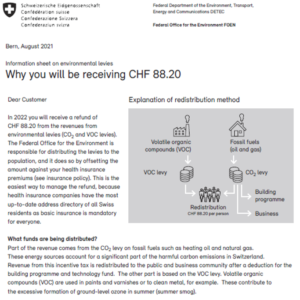

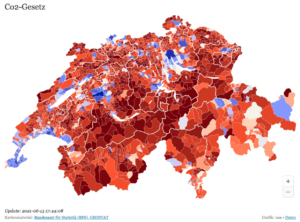

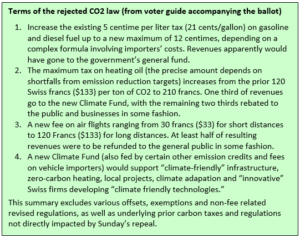

To be sure, some observers did notice aspects of this political shift before election day. But dots were unconnected and potential impacts discounted. Traveling the countryside in the weeks before the election, the head of the Swiss Farmers Association says he was astonished that “every remote hamlet” of rural Switzerland had posters up opposing the “leftist” CO2 law and arguing for its rejection by voters.

To be sure, some observers did notice aspects of this political shift before election day. But dots were unconnected and potential impacts discounted. Traveling the countryside in the weeks before the election, the head of the Swiss Farmers Association says he was astonished that “every remote hamlet” of rural Switzerland had posters up opposing the “leftist” CO2 law and arguing for its rejection by voters.