Here we cross-post my article published in The Washington Spectator magazine yesterday, under the headline, A Carbon Tax With Legs. Except for a handful of line edits below, the two versions are the same.

For years, carbon tax advocates scoffed at the notion that Exxon-Mobil would back a tax on climate-damaging carbon pollution. We saw through the vague hypotheticals in which the oil giant cloaked its occasional expressions of support. Rather than invest political muscle in carbon tax legislation, Exxon for decades funded a network of deception that blocked meaningful action on climate.

So why are we taking notice that this past June Exxon formally endorsed a so-called Republican carbon tax plan? And why am I not up in arms that the plan entails granting Exxon and other fossil fuel owners immunity from legal damages for the climate havoc caused by extracting and burning these fuels?

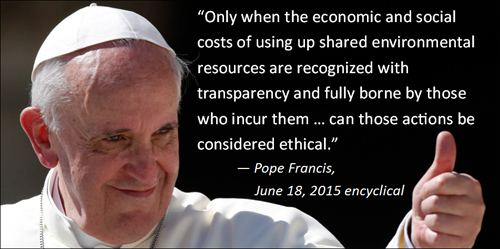

It comes down to two reasons. First, there’s little chance that oil, coal, and gas companies could ever be made to pay more than token amounts for the ruin their products cause. Second, though bankrupting big oil may seem appetizing, it’s a distraction from the real goal of “demand destruction” — shrinking and eliminating the use of carbon-based fuels. The fastest path to that goal is through a robust carbon tax that manifests the harms caused by those fuels in the prices the marketplace sets for oil, coal, and gas, as the new proposal would do.

The carbon tax plan is dubbed “Republican” because its public faces are those of George Shultz and James Baker, exemplars of the outcast center-right GOP establishment. Two factors set this plan apart from current Republican orthodoxy.

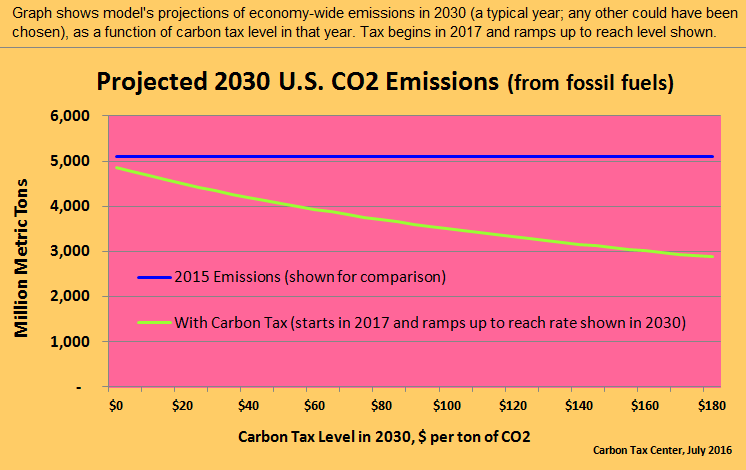

First, the Shultz-Baker tax is no slouch. It would start at $40 per ton of carbon dioxide and rise from there, putting it miles above anything floated by oil companies or Republican officeholders. The price is high enough not only to nail the coffin on coal, by far the dirtiest fossil fuel, but also to put a serious dent in oil usage.

After a decade, according to my modeling, U.S. carbon emissions would be 27 percent less than last year and 36 percent less than in 2005, the standard baseline year in climate analysis.

Second is the equitable distribution of the carbon tax proceeds. They would be disbursed to American families as “dividends,” with equal revenue slices for all. This approach is not only income-progressive, making it a black swan among Republican policy ideas; it also buys support for raising the tax level over time, since the dividends would rise in tandem.

The Shultz-Baker tax may actually have political legs. While the current White House and Congress are tribally bound to vilify anything smacking of Al Gore or Barack Obama, the 2018 midterms and the 2020 presidential election could bring a reckoning on climate policy. With a majority of Americans in a recent poll calling climate change “extremely or very important” to them personally, Republicans may soon be seeking an escape hatch.

Three attributes in the Shultz-Baker proposal meant to win over the center-right are anathema to progressive elements in the climate movement. We can call them: no investment, no regulation, and no litigation.

“No investment” means dedicating the carbon revenues to the dividend checks, leaving none for government to construct carbon-free energy and transportation systems or to remediate the “frontline” communities most ravaged by fossil fuel infrastructure. Yet economists are convinced that the price-pull of the carbon tax will bring about this transition.

“No regulation” means rescinding EPA climate rules, principally the Obama-era Clean Power Plan prized by environmental powerhouses like the Sierra Club. But the Clean Power Plan is nearly “mission accomplished”: its target is already four-fifths met (and rising) as coal-fired electricity production is eaten away by natural gas, rising wind and solar power, and energy efficiency.

Finally, “no litigation” means letting carbon corporations and shareholders off the hook for producing and promoting their climate-ruining products — a bitter pill for the broad and insistent fossil fuel divestment and “Exxon knew” movement spearheaded so effectively by Bill McKibben. Yet would that be a grievous loss? Not according to Michael B. Gerrard, who directs the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School: “No lawsuits anywhere in the world seeking to hold fossil fuel companies liable for climate change have succeeded,” Gerrard told me recently via email. “Losing the ability to sue these companies for climate change would not be giving up a huge amount if it were in exchange for a large enough carbon tax.”

So is the promised carbon tax large (and solid) enough to justify dealing away the triad of litigation, investment, and regulation? My colleagues and I at the Carbon Tax Center believe it is.

The proposal is gathering steam. Not just Exxon but a dozen other corporations, including General Motors, Procter & Gamble, Unilever, Pepsico, and three other oil companies (Shell, BP, and Total) formally endorsed the plan in June, along with the Nature Conservancy and the World Resources Institute. The political path for the Shultz-Baker carbon tax, not much wider than a human hair when it was launched last winter, is broadening rapidly.

Charles Komanoff, an economist, directs the Carbon Tax Center in New York City.