(This post was amended on March 31 to include rebuttals of our criticism of the Montana climate-change lawsuit from two distinguished participants.)

Climate agitation was much in the news last week. The Guardian reported on a forthcoming Harvard Environmental Law Review paper suggesting that fossil fuel companies could be held liable for homicide from deaths caused by climate change. A New York Times front-page story previewed a courtroom trial to determine if Montana policies promoting fossil fuels violate that state’s constitutional protections of a healthful environment. And in dozens of cities, activists assembled by noted climate author-organizer Bill McKibben tore up their Chase, Citi, Wells Fargo and Bank of America credit cards to spotlight the big banks’ financing of $1 trillion in fossil fuel projects over the past five years.

In other climate news, however, suburban legislators are contesting a bold initiative from New York Gov. Kathy Hochul to compel New York City and surrounding counties to expand housing supply. New York City’s public transit provider is scrounging for revenues to shore up declining subway and bus farebox receipts stemming from the triple-whammy of residual Covid worries, violent-crime fears, and working-from-home. Around the country, meanwhile, just about all of the gargantuan road-widening projects listed in U.S. PIRG’s most recent Highway Boondoggles report are proceeding apace.

“States’ rights” have become “local control.” L: Wallace for President rally, 1972, courtesy Google Images. R: Ryan Lowry for the NY Times, accompanying March 22, 2023 opinion essay, “NIMBYs Threaten a Plan to Build More Suburban Housing,” by Times editorial writer Mara Gay. Photo was captioned, “Legislators protested Gov. Kathy Hochul’s housing plan in Albany on Monday.” Faces and demographics in the two photos, taken more than half-a-century apart, are hard to distinguish.

Yes, we’re juxtaposing.

The three just-noted happenings threaten to lock in place profligate fossil fuel consumption and associated carbon emissions. Highway widenings engender more driving (“induced demand,” it’s called). Fare hikes and service cuts to transit in NYC and elsewhere will do the same. And bottling up housing supply, as New York’s suburbs and my own borough of Manhattan, along with affluent cities and towns all over the U.S. have been doing for decades, guarantees urban stasis and its evil twin of exurban sprawl, with its accoutrements of carbon-spewing SUV’s, manses and subdivisions — not to mention segregation.

Litigating for Climate

These carbon accelerants might be more bearable if the climate agitation mentioned at the top had genuine prospects for cutting emissions. Do they? Not likely.

Indicting, much less convicting, officers of fossil fuel companies for killing people via their emissions-induced climate change is the definition of quixotic — to my untutored eye, anyway. In court, Big Oil will simply point to the tens of billions of lives uplifted by the fruits of their fuels. And they won’t be spouting nonsense. The raising up of most of humankind out of subsistence, and the resulting cradle-to-grave lengthening of human lifespans, could not have happened without the carbon-fueled Industrial Revolution. Set against those numbers, the millions — if that — of lives provably lost because of climate change will appear as a mere rounding error.

To be sure, the still-rising use of fossil fuels globally has now burst past the point of positive net benefits, especially with the advent, at last, of scalable non-carbon ways to power civilization. But actually effectuating the transition seems a matter for politics, with or without judicial support.

And even if some clarion guilty verdict were rendered in some court, what would be the remedy? Would the fossil fuel industry be made to dismantle itself? What about the billions of motorists, manufacturers and other consumers and producers who would clamor for more. Sorry, there’s no bypassing the messy work of using pricing, regulation and innovation to get off fossil fuels.

I’m almost as skeptical re the Montana litigation — notwithstanding the earnestness of the young plaintiffs, including two brothers who not only are the sons of firearms-industry apostate Ryan Busse but who were motivated to join the lawsuit by the climatological deterioration of their beautiful corner of northwest Montana.

I identify with Lander and Badge Busse. Melting snow in nearby Glacier National Park helped trigger my ecological awakening, but in an opposite fashion from theirs. On a long-ago day in July, driving on the park’s Going-to-the-Sun Road with my grade-school pal, I parked our tiny Renault auto to fetch water dripping from roadside snowbanks. We filled our canteens and started walked uphill toward the source. An hour later, we were a thousand vertical feet above the roadway and following real-life mountain goats under an impossibly blue sky. Bookending our hike into the Grand Canyon a week earlier, that day became my gateway into love of wildness, defense of clean air, and a career in environmental policy analysis and activism.

Most of Glacier’s glaciers are now diminished if not gone, making the lawsuit, Held v. State of Montana, painful as well as valiant. Yet even if the brothers and their co-litigants win their case, what exactly is the remedy? The Montana Supreme Court possesses no magic button whose pressing can end the burning of fossil fuels. Stop drilling or mining in Montana, and producers will up their output from Wyoming. Stop it in all 50 states, and the same suppliers will boost production overseas. Sure, impeding fuel extraction will incrementally drive up fuel prices and take a bite out of demand, but that’s just a sideways blow at best. The solution, as CTC has argued since our founding in 2007, lies in throttling demand for carbon, not stoppering supply.

Montana litigation supporters weigh in

Shortly after this post went up, CTC received this brief rebuttal from a long-time supporter of the Montana suit and the larger Our Children’s Trust campaign to enshrine a legal right to a safe climate:

The Montana climate suit seeks to build case law affirming a right to a stable, livable climate. I liken it to the long-term legal struggle to secure equal treatment under the law for women and people of color. For example, the legal battle to desegregate schools was a long one built on case law. I agree that any individual state has limited ability to impose a price on emissions, but the Juliana vs. U.S. suit does. It seeks a science-based reduction in emissions sufficient to maintain a stable, livable climate, and proposes a carbon tax as the single most effective policy to achieve that goal. Likely the courts will only impose emission reductions. Politicians will then be tasked with submitting a plan that is affordable and effective. The Montana and other suits build case law affirming the damage caused by fossil fuel emissions and a right to a livable climate. Courts act more on evidence and less on short-term political pressure.

We also received this note from noted environmental attorney and climate-law expert Michael Gerrard, who directs the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School and was featured in the New York Times story noted at the top of this post:

I think we need to attack both the demand side and the supply side. No one action will affect the supply on a macro scale, but cumulatively many could. Montana is one of the nation’s largest fossil fuel suppliers, and if the courts shut down some of that, it would be a good thing. The judge, at least, is taking the case seriously. Whether or not the Montana Supreme Court upholds a decision for the plaintiffs, the case will cast a harsh light on the fossil fuel companies. Most of these campaigns are largely aimed at delegitimizing the fossil fuel companies and reducing their political clout. That is having some effect in blue states, where quite a few strong climate laws are being enacted over the opposition of the fossil companies. And keep in mind that each new coal mine, each new gas-fueled power plant, and so forth, creates a constituency for its long-term preservation; that needs to be resisted.

CTC collage from two separate photographs on Third Act website, snipped on March 30, 2023.

Banks and Climate

We come now to last week’s bank protest that Bill McKibben organized with his new “Community of Americans,” Third Act.

As much as I admire Bill’s unflagging zeal and his Third Act cohorts’ earnest willingness to put themselves out there, I strongly question targeting banks as a cause of fossil fuel exploitation and a locus for climate activism.

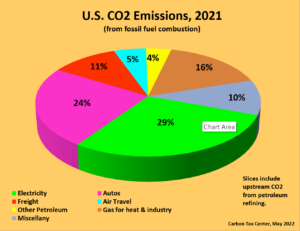

How will bank reformation impact the use of cars, trucks and planes in the U.S. or elsewhere — use that requires purchases of gasoline, diesel and jet fuel that in turn provide both the financial wherewithal and the political muscle to drill, extract, refine and transport petroleum products whose combustion releases the carbon dioxide that is wrecking our climate?

Should not Third Act and indeed the entire climate movement be organizing and demonstrating for demand-cutting policies and developments such as mixed-use and dense housing, functional-or-better public transportation, bikeable and walkable streets, fuel-economy standards without “light truck” loopholes, and the like? Wouldn’t their energies accomplish more, both short- and long-term, if they were to swarm Albany and other state capitals to demand upzoning, no more highway widenings, and permitting reform to circumvent anachronistic regulations hindering wind farms and solar homes?

In response, Bill would probably say “We need to remind people of the connection between cash and carbon. Literally, somebody who has $125,000 in those banks [Chase, Citi, Wells Fargo, Bank of America] is producing more [carbon] because it’s being lent out to pipelines and frack wells than all the cooking, flying, heating, driving, cooling that the average American does in a year. Five thousand dollars in [those banks] produces more carbon than flying back and forth across the country.”

How do I know? Because that’s exactly what he said on Democracy Now on the morning of the protests (quoted segment begins around 37:45). Try as I might, I can’t follow the logic.

Coda

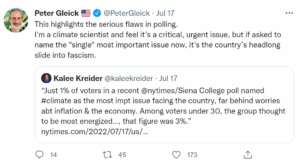

Notice I haven’t mentioned carbon pricing, except tangentially. Here at CTC we’re laying low on carbon taxing for the time being. U.S. politics still aren’t ready, what with climate-averse Republicans occupying half of Congress, and Democrats wary of the difficult politics. We focus on what’s possible in the here-and-now.

Last year it was the praiseworthy (if imperfect) Biden-Schumer Inflation Reduction Act. This year we’re continuing to do what we can to bring congestion pricing for New York City into being. We’re also quietly nurturing a promising new avenue to advance a New York State carbon price. Please stay tuned!

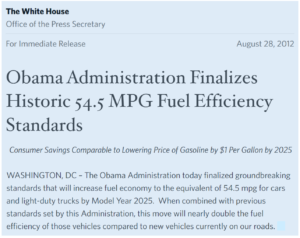

The supposed impossibility of reducing the use of gasoline by raising its price has been part and parcel of Big Green’s attachment to mpg standards — despite the fact that mileage reg’s do nothing to reduce driving and its vast negative consequences: not just traffic congestion but also poor health (sedentary living, car crashes, noise) and general unaffordability (car loan costs, upkeep expenses, costlier housing due to cars’ consuming urban and suburban land).

The supposed impossibility of reducing the use of gasoline by raising its price has been part and parcel of Big Green’s attachment to mpg standards — despite the fact that mileage reg’s do nothing to reduce driving and its vast negative consequences: not just traffic congestion but also poor health (sedentary living, car crashes, noise) and general unaffordability (car loan costs, upkeep expenses, costlier housing due to cars’ consuming urban and suburban land).

They had to move quickly before military police, tasked with securing the airport, saw what was happening. The rebels targeted 13 private jets parked or preparing for takeoff, at least two belonging to NetJets, the Berkshire Hathaway subsidiary that bills itself as the world’s largest jet company and sells fractional ownership shares in private business jets.

They had to move quickly before military police, tasked with securing the airport, saw what was happening. The rebels targeted 13 private jets parked or preparing for takeoff, at least two belonging to NetJets, the Berkshire Hathaway subsidiary that bills itself as the world’s largest jet company and sells fractional ownership shares in private business jets. The justification is unarguable. Large personal fortunes feed carbon consumption and make a mockery of programs to curb it. As well, the surplus wealth of the superrich is probably the lone source of capital that can finance the worldwide uptake of greener energy and also pay for adaptation where it’s most critical.

The justification is unarguable. Large personal fortunes feed carbon consumption and make a mockery of programs to curb it. As well, the surplus wealth of the superrich is probably the lone source of capital that can finance the worldwide uptake of greener energy and also pay for adaptation where it’s most critical. “What the Schiphol people needed to do is destroy the airplanes on the tarmac and then destroy the airplane manufacturers,” said an ecosaboteur named Stephen McRae, an acquaintance of one of the authors, who recently completed a six-year prison sentence for industrial sabotage. Although he no longer participates in such criminal acts of destruction, he has a point. The planes grounded on November 5 are already back in the air. That doesn’t diminish the value of what the Schiphol rebels did, however. Actions that disrupt carbon comfort without violence or hardship are morale-building, the material from which more actions and eventually mass movements are made.

“What the Schiphol people needed to do is destroy the airplanes on the tarmac and then destroy the airplane manufacturers,” said an ecosaboteur named Stephen McRae, an acquaintance of one of the authors, who recently completed a six-year prison sentence for industrial sabotage. Although he no longer participates in such criminal acts of destruction, he has a point. The planes grounded on November 5 are already back in the air. That doesn’t diminish the value of what the Schiphol rebels did, however. Actions that disrupt carbon comfort without violence or hardship are morale-building, the material from which more actions and eventually mass movements are made.

The Inflation Reduction Act likewise marks a turning point, at least for the time being, on long-running, world-damaging U.S. climate helplessness. True,

The Inflation Reduction Act likewise marks a turning point, at least for the time being, on long-running, world-damaging U.S. climate helplessness. True,

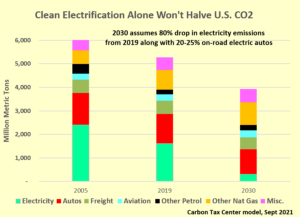

Even a fully intact Biden plan would have fallen short of its goals. Nevertheless, its scope and reach would have far surpassed any climate program by any major nation. Build Back Better’s carbon reductions and climate benefits would have been numerically substantial and would also have triggered parallel policies in other countries.

Even a fully intact Biden plan would have fallen short of its goals. Nevertheless, its scope and reach would have far surpassed any climate program by any major nation. Build Back Better’s carbon reductions and climate benefits would have been numerically substantial and would also have triggered parallel policies in other countries. During the run-up to that vote we published

During the run-up to that vote we published  D. Like Andreas Malm, we believe that direct action in defense of climate and earth needs to come to the fore, as we proposed in two posts last summer inspired by Malm’s book: Christopher Ketcham’s essay,

D. Like Andreas Malm, we believe that direct action in defense of climate and earth needs to come to the fore, as we proposed in two posts last summer inspired by Malm’s book: Christopher Ketcham’s essay,

No federal legislation with a price on carbon has advanced to a floor vote since the “Waxman-Markey”

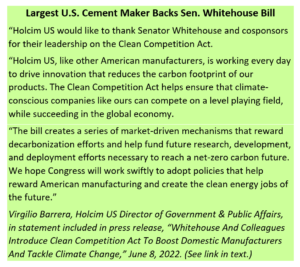

No federal legislation with a price on carbon has advanced to a floor vote since the “Waxman-Markey”  Whitehouse sees his bill as a way to use U.S. trade policy to drive climate action. He also views its potential to boost U.S. industrial competitiveness as a way to attract bipartisan support. Holcim U.S., whose parent company, Lafarge Holcim, is America’s largest cement manufacturer,

Whitehouse sees his bill as a way to use U.S. trade policy to drive climate action. He also views its potential to boost U.S. industrial competitiveness as a way to attract bipartisan support. Holcim U.S., whose parent company, Lafarge Holcim, is America’s largest cement manufacturer,