Our post last Friday about Build Back Better was already pushing the boundaries by contending that the Biden infra plan won’t actually cut CO2 50% by 2030, when we added this at the end:

We suspect that even a starter, “proof of concept” carbon tax at this time will prove to be a poor idea. Passing a carbon tax in lieu of aggressively raising taxes on high income and instituting taxes on great wealth, as several Senate Democratic climate hawks floated today, amounts to budget-balancing on the backs of both the working poor and the beleaguered middle class. It’s inequitable and a terrible template for the really large carbon taxes that progressive Democrats must eventually enact, in the event they ever reach centrist-proof majorities.

But wait: CTC is supposed to be supporting efforts to pass a U.S. carbon tax. Why, then, were we throwing darts at the Senate Democrats’ trial balloon that was aimed at doing just that?

We have four reasons:

- We don’t think Congress can pass a carbon tax in 2021 anyway.

- We believe the carbon tax under discussion won’t offer sufficient protection to ordinary Americans.

- We doubt that any carbon tax under discussion can generate big enough emission cuts.

- We fear that Democratic backing for a carbon tax at this time will make it harder to defeat the climate-denying G.O.P. in the 2022 midterms.

Things were moving fast last Friday afternoon and we weren’t able to polish our remarks. Now, with a bit more time, let’s unpack these points.

1. Congress can’t pass a carbon tax in 2021 anyway.

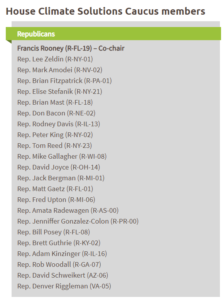

The make-or-break Senate votes aren’t there. Manchin of West Virginia won’t vote for a carbon tax, Sinema of Arizona can’t be counted on, and it wouldn’t be surprising if a few Senate or House Democrats facing tough re-elections defected as well. And no Republicans will come on board. Carbon-tax proponents and other climate hawks have waited in vain for over a decade for a single sitting Republican member of the Senate to stand up for strong climate action just once. There’s no reason to think our prayers are about to be answered.

2. The carbon tax under discussion won’t protect enough ordinary Americans.

President Biden has pledged not to raise taxes on Americans earning less than $400,000 a year. A straight-up fee-and-dividend, which is the type of carbon tax CTC most strongly favors, would violate that en masse, despite being strongly income-progressive.. The reason: most six-figure households are high-carbon consumers and thus would be carbon-taxed more than they would be dividended.

If you’re unsure about that, consider the main finding of Anders Fremsted and Mark Paul’s superb 2017 paper for U-Mass’s Political Economy Research Institute, A Short-Run Distributional Analysis of a Carbon Tax in the United States: While 84 percent of households in the bottom income half would be made better off with carbon dividends, only 55 percent of all households would be beneficiaries. Simple arithmetic on those two propositions indicates that only 26 percent of the more affluent households would benefit. (The calculation: 84% of the bottom half equals 42% of all households. The remaining 13 percentage points of beneficiaries constitute just 13%/50%, or 26%, of the top half.) The optics of squaring such a carbon tax or fee with the pledge aren’t promising.

(If Fremsted and Paul’s finding seems too pessimistic, consider this alternative scenario: if 90 percent of bottom-half households were posited as better off, and same for 65 percent of all households, then the share of upper-half households being made better off would come to 40 percent — higher than the 26 percent above, but still a minority of that group.)

To be clear, CTC has no qualms about raising taxes on the very-affluent as well as the super-rich to make a better society. But raising taxes on the working poor and the beleaguered middle class is another matter entirely. And to the extent that the carbon tax under discussion is meant as a pay-for — literally, to pay for improving America’s physical and social infrastructure — less money will be available for dividends. It’s one thing to set aside a few percent of carbon fee revenues to pay for worker and community transitions, as outspoken climate hawk Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) proposed this summer; but it’s another thing altogether to set aside, say, 25 percent for pay-for’s. Having only 75 percent of carbon revenues available for dividends will consign millions of non-affluent households to paying more for energy and energy-intensive goods than they receive as dividends.

To be clear, CTC has no qualms about raising taxes on the very-affluent as well as the super-rich to make a better society. But raising taxes on the working poor and the beleaguered middle class is another matter entirely. And to the extent that the carbon tax under discussion is meant as a pay-for — literally, to pay for improving America’s physical and social infrastructure — less money will be available for dividends. It’s one thing to set aside a few percent of carbon fee revenues to pay for worker and community transitions, as outspoken climate hawk Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) proposed this summer; but it’s another thing altogether to set aside, say, 25 percent for pay-for’s. Having only 75 percent of carbon revenues available for dividends will consign millions of non-affluent households to paying more for energy and energy-intensive goods than they receive as dividends.

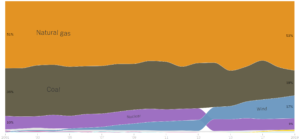

3. The carbon tax under discussion won’t generate big emission cuts.

This objection is somewhat speculative because, perhaps understandably, no Senate Democrat has yet attached a level to their carbon tax trial-balloon. But there’s a tendency to overstate what a modestly-sized carbon tax can accomplish.

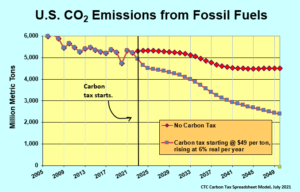

For example, Resources for the Future, the influential environmental think-tank cited in last Friday’s New York Times story that touched off the latest carbon tax discussion, projects that a carbon tax that starts in 2023 at $15 per metric ton, rises slowly to $30 in 2028 and then jumps to $50 in 2030, will cut CO2 emissions in that year by 44 percent from 2005 levels. That would represent an 1,850 megatonne drop in emissions from 2019. But plugged into our carbon tax model, those inputs yield only a 775 megatonne drop, or much less than half as much. To be sure, RFF’s modeling also includes a clean electricity standard (a close cousin of the Clean Electricity Performance Program in the Biden package that we discussed in our earlier post), but the CEPP would be partly duplicated by the carbon tax and thus wouldn’t account for the bulk of the difference between our respective model results.

Would we support the more modest RFF carbon tax nonetheless if it could be guaranteed to be economically progressive in the aggregate? You bet we would. Our concern on this score is what we telegraphed in our Sept 27 post: the need to neutralize undeserved hype being vested in any climate policies, including carbon taxes.

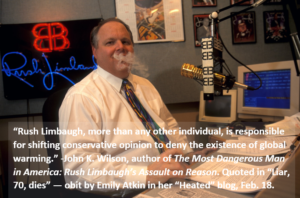

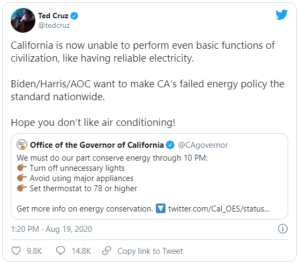

4. Democratic backing for a carbon tax now will make it harder to defeat the climate-denying G.O.P. in the 2022 midterms.

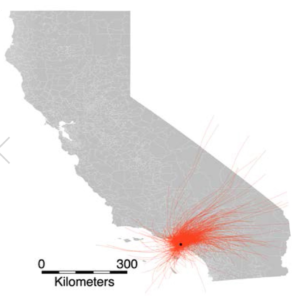

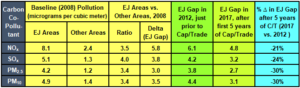

We won’t belabor this point. Too much depends on the Democrats’ retaining full control of Congress in next year’s midterms and having a good shot at holding on to the White House in 2024. We believe a lot more organizing, educating and communicating about the power, fairness and benefits of carbon taxes remains to be done before the party is somewhat safely inoculated against the inevitable blowback against even an economically progressive carbon tax. Much of that effort will need to go into bringing environmental justice and other progressive activists into the fold.

What kind of carbon tax does the Carbon Tax Center want?

CTC wants a carbon tax that can pass, that’s certifiably progressive (economically), that is robust enough in its per-ton rate to be able to help eliminate game-changing amounts of CO2 and fossil fuels, and that won’t cause gross damage to the Democratic Party’s brand and thus make it easier for the Trumpian right to regain power.

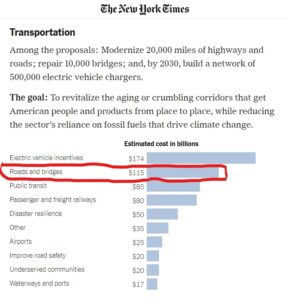

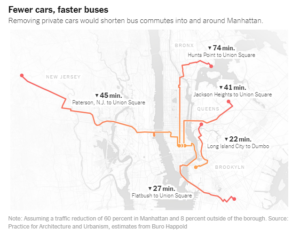

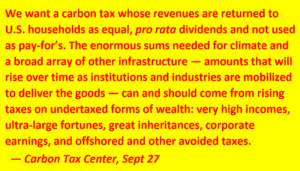

Translated: We want a fee-and-dividend carbon tax, i.e., a carbon fee whose revenues are returned to U.S. households as equal, pro rata dividends and not used as pay-for’s. The enormous sums needed for climate and a broad array of other infrastructure — amounts that will rise over time as institutions and industries are mobilized to deliver the goods — can and should come from rising taxes on undertaxed forms of wealth: very high incomes, ultra-large fortunes, great inheritances, corporate earnings, and offshored and other avoided taxes.

This structure will let the carbon tax rise steadily over time and perform the function it does best: instill the price incentives and social signals to steer U.S. households, businesses, habits and norms away from fossil fuels and into the broad array of alternatives — everything from bicycles and denser living patterns to wind turbines and solar roofs — that won’t heat our climate beyond repair.