Even in ecologically-minded Washington and Oregon, states where voters want government action on climate change, a divide among environmentalists threatens to undermine progress on the issue. A Carbon Washington ballot initiative to create a statewide carbon tax is gaining momentum, as we wrote last month. Yet several environmental groups are attacking the proposal as politically infeasible and socially regressive.

Instead, state and regional groups like Climate Solutions and the Alliance for Jobs and Clean Energy are pushing “clean” fuels standards. Their proposal, patterned on regulations in California and British Columbia, would mandate a mere 10% drop in the carbon intensity of transportation fuels over 10 years ― a small fraction of the deep reductions needed.

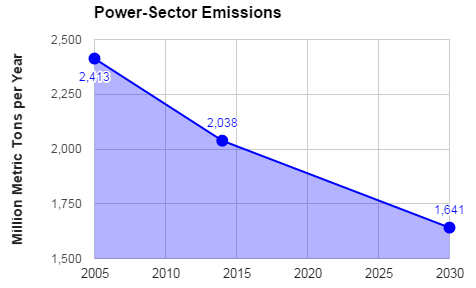

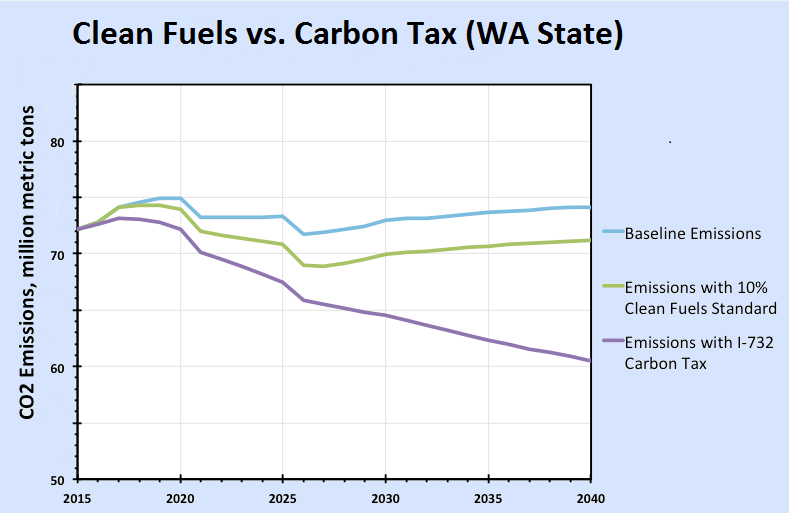

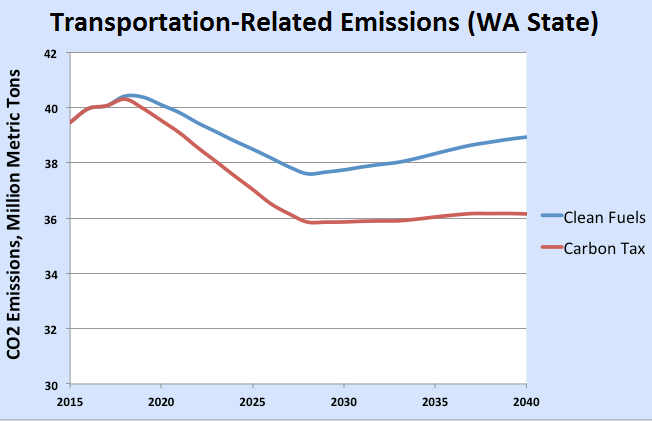

The carbon tax sought by Carbon Washington would cut CO2 4-5 times as much as the proposed WA Clean Fuels Standard (Source: CTAM).

Their course is difficult to fathom. Carbon taxes would cut emissions more and cost less than clean fuels regulations. And dividing environmentalists in order to pursue a lesser policy makes no sense strategically. Here are three reasons why a clean fuels standard doesn’t stack up:

1. Clean fuels standards won’t be effective

A model used by the Washington State Department of Commerce allows us to compare projected emissions reductions from the clean fuels standard with the carbon tax proposed by Carbon Washington in a measure known as I-732. (The tax would start at $10/ton of CO2, rise to $25 in year two, then increase 3.5% annually plus inflation.)

The 10% clean fuels standard would lower overall Washington CO2 emissions only 4% by 2040, not even a quarter as much as the 18% reduction projected from the I-732 carbon tax.

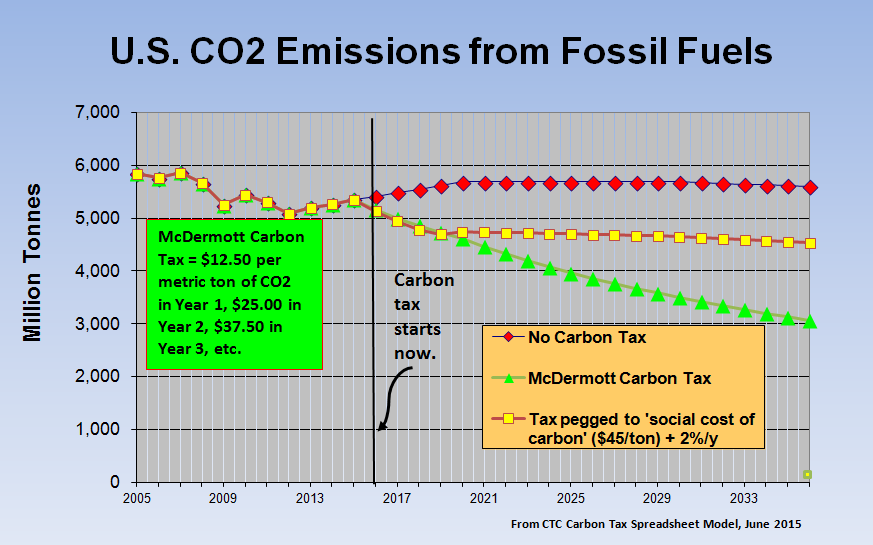

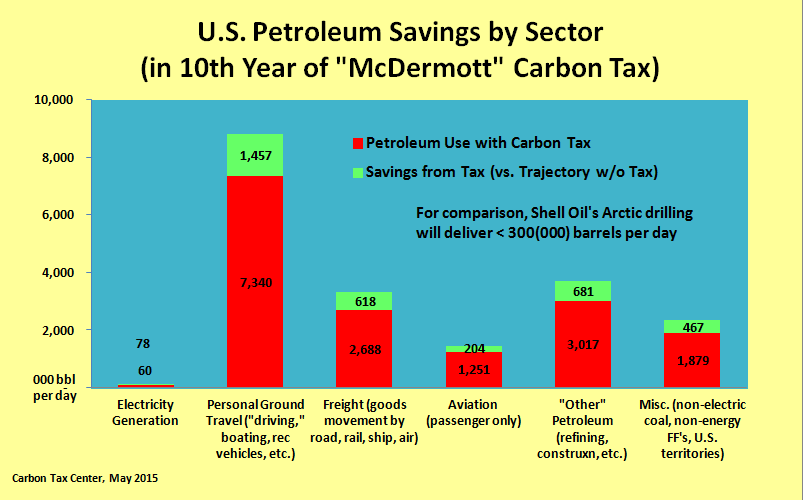

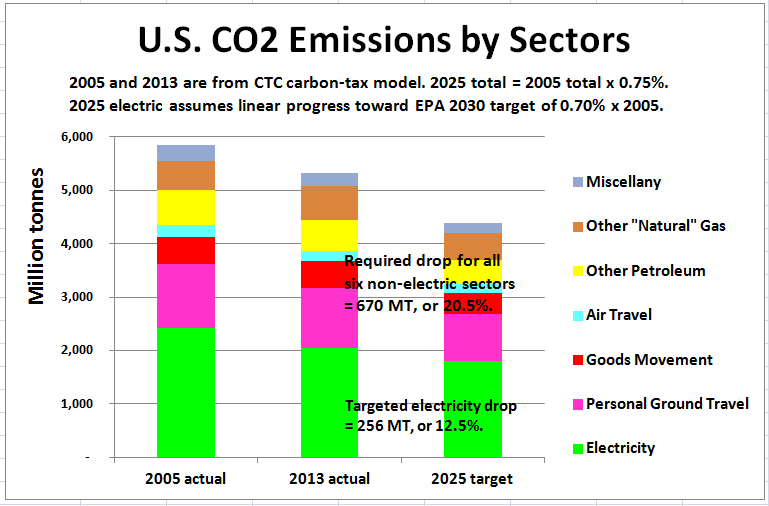

The reason is simple: a clean fuels standard only attacks emissions from the supply side of one sector, albeit an important one, transportation. In contrast, a carbon tax works across the entire economy, influencing every carbon-related decision about both supply and demand in every sector ― manufacturing, heating, electricity, etc. This means that, while a clean fuels standard only affects the carbon content of liquid fuels, a carbon tax also incentivizes less fuel usage, period. This transforms economies, cutting pollution and congestion through a vast array of actions encompassing urban density, freight logistics, walking, cycling, transit, and more mindful decision making.

In short, the difference in emissions between a carbon tax and a clean fuels standard is the difference between a society that takes current levels of automobile dependence as a given, and one that seeks to support a myriad of ways to transition to something different.

In short, the difference in emissions between a carbon tax and a clean fuels standard is the difference between a society that takes current levels of automobile dependence as a given, and one that seeks to support a myriad of ways to transition to something different.

2. Clean fuels standards are more expensive

The Oregon Environmental Council writes:

The Clean Fuels Program costs the state virtually nothing. The burden of responsibility for reducing pollution is placed on the oil industry.

This conspicuously ignores how the oil industry passes down its costs of compliance to consumers in the form of higher prices. The Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) has said gas prices will rise between 4 and 19 cents per gallon. An industry lobby group, the Western States Petroleum Association, is garnering support to repeal clean fuels by highlighting this not-so-hidden price increase.

Consumers aren’t stupid, they generally realize more regulations mean higher prices. A carbon tax raises fossil fuel prices too, of course ― that’s the point; but the revenue it generates can be disbursed to consumers as income or sales tax cuts, or via a straight-up “dividend” check, as Oregon Climate has proposed. [Read more…]