A clean electricity boom is the main reason U.S. carbon emissions fell between 2005 and 2019. We’ve calculated the CO2 not emitted because electricity usage has flattened instead of growing with economic output. The upshot: “clean electricity” (power savings + renewables) is replacing more coal and pushing out more CO2 than is fracked gas — and without the climate-damaging methane emissions released in fracking.

In late 2016, CTC announced what we called “the good news” of the U.S. electric power sector’s rapid decarbonization. Our December 2016 blog post and its accompanying report quantified the power sector’s 25 percent reduction in carbon emissions from 2005 to 2016 and clarified what accounted for it.

That report, “The Good News: A Clean Electricity Boom Is Why the Clean Power Plan Is Way Ahead of Schedule,” showed that while substitution of fracked gas for dirtier coal contributed to reducing emissions, a greater role was played by clean electricity: an upsurge in electricity production from renewables (wind turbines and solar photovoltaic cells), and electricity savings that caused electricity usage to flatten even as economic output increased.

Now, in an updated version of that report, we extend those findings with new data through 2019, and the results are impressive and satisfying.

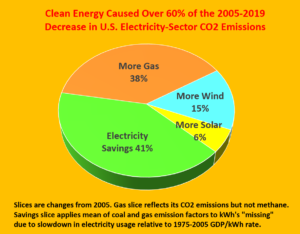

We find that in 2019 U.S. electricity sector emissions of carbon dioxide were 33 percent below 2005 levels, thus surpassing, eleven years ahead of schedule, the Obama Administration’s Clean Power Plan goal of a 32 percent cut in electricity-generation carbon emissions from 2005 to 2030. We estimate that 62 percent of the electricity sector’s carbon reduction since 2005 has been due to clean electricity, with the other 38 percent due to substitution for coal by natural gas.

This finding depends critically on the fact that from 2005 to 2019, total U.S. generation of electricity rose by a mere 2.4 percent — equivalent to an annual average growth rate of just 0.17 percent — even as the U.S. economy, measured imperfectly yet officially by Gross Domestic Product, expanded by nearly 28 percent. The majority contribution to electricity decarbonization of clean electricity belies the prevailing narrative crediting fracked gas for the lion’s share of the reduction in coal burning and the resulting lowering of carbon emissions.

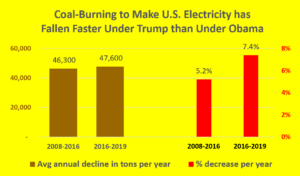

Our new report, “The Good News Trump Couldn’t Kill: The Clean Electricity Boom Is Doing More Than Fracking To Decarbonize America’s Power Sector” (download as pdf), also finds that the burning of coal to make electricity in the U.S. shrank at a faster clip during the Trump administration (2019 vs. 2016) than over the course of the Obama administration (2016 vs. 2008). The respective annual decline rates in tons per year were 47,600 (Trump) and 46,300 (Obama); expressed as percentages, the respective annual decline rates were 7.4 percent per year (Trump) and 5.2 percent (Obama). (The average percentage difference between the Trump and Obama years is greater than the tonnage difference because of the Trump years’ lower baseline level.)

The free fall in use of coal to make electricity has been widely reported. The role of electricity saving has not. This is partly due to the difficulties of quantifying electricity savings and of booking those savings as reductions in uses of particular fuels. (Our solutions are to calculate the savings relative to hypothetical electricity generation if the 1975-2005 relationship between electricity growth and economic growth had continued; and to assign half of the reduced kilowatt-hours to coal and the other half to natural gas.)

The free fall in use of coal to make electricity has been widely reported. The role of electricity saving has not. This is partly due to the difficulties of quantifying electricity savings and of booking those savings as reductions in uses of particular fuels. (Our solutions are to calculate the savings relative to hypothetical electricity generation if the 1975-2005 relationship between electricity growth and economic growth had continued; and to assign half of the reduced kilowatt-hours to coal and the other half to natural gas.)

But the failure to give electricity saving its due runs deeper. The penetration of energy-saving digital technologies in energy management, product design and manufacturing isn’t an eye-catching subject. Neither is the emergence of a business sector that finds, finances and delivers money-saving efficiency improvements in commercial and apartment buildings. Nevertheless, both phenomena are widespread and robust. So are ratepayer-funded energy-efficiency programs mandated by state public utility commissions, often with the insistence (and guidance) of tenacious and knowledgeable environmental groups.

Nevertheless, the flattening of U.S. electric usage and generation from the 7% annual growth rates that prevailed for most of the first three-quarters of the 20th century, down to 2.5% average growth from 1975 to 2005, and to just 0.2% per year annual growth from 2005 to 2019, is a profound development warranting much greater attention. We hope publication of this updated “Good News” report will help spur this notice.