CTC policy associate Bob Narus wrote last month that Carbon Tax Advocates Should Embrace a Green New Deal. Here is his mirror-image brief for including a robust carbon tax in a Green New Deal.

The Green New Deal isn’t a policy yet. Right now, it’s mostly an aspirational slogan and a set of bullet points, which is fine for the moment. There’s time to work out the policy details. But it’s important that a robust carbon tax become one of those bullet points, because without it no deal, no matter how new and green, can do everything we need to do to prevent global climate change from spinning out of control.

Rally in Victoria, BC, March 2019. Photo courtesy of Anne Hansen.

Whether a carbon tax is part of the Green New Deal depends on whose Green New Deal you mean. The Data for Progress report, A Green New Deal — essentially Document Zero for the Green New Deal movement — doesn’t endorse a carbon tax but does note that “there is new analysis that a carbon tax will not hamper the economy, particularly as revenues are reinvested smartly in communities.”

The Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez/Ed Markey resolution, H.R. 109/S.R. 59, doesn’t mention a carbon tax, or any other potential source of funding for its ambitious goals, but AOC herself has publicly recognized the need for taxes to internalize the externalities of some industries or markets.

The policy details will fall into place over time. In particular, one hopes the many Democratic presidential candidates who have endorsed a “Green New Deal” will say more about what they mean by that — which policies they would include, what they’ll cost, how to pay for it all.

In short, we will have a national conversation about the Green New Deal. To everyone engaged in that conversation, here’s a quick take on why a carbon tax should be part of it:

1. If you believe the IPCC, we have to do everything.

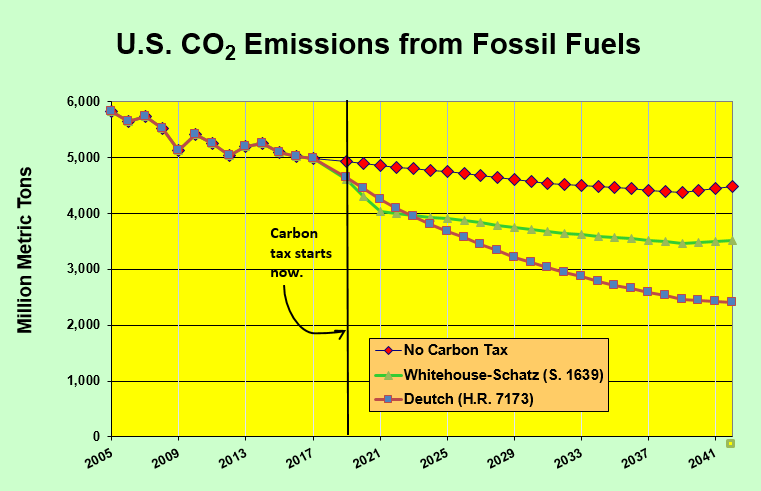

In its most recent report, the IPCC called for roughly halving (from 2010 levels) world carbon dioxide emissions by 2030. Achieving that in the U.S. would require a 5 percent annual decrease in carbon emissions from fossil fuels, which would quadruple the actual rate of decline from the mid-aughts to 2017 (see technical note at end). And right now we’re going in the wrong direction: The Rhodium Group estimates that U.S. CO2 emissions rose 3.4 percent in 2018.

With a challenge like that ahead of us, we can’t afford to take any option off the table. As I argued recently, a carbon tax alone will not do the job. But neither will anything else. We need to throw everything we’ve got at the climate crisis, and that definitely includes the most economically efficient tool.

2. A carbon tax will make everyone a partner in the effort.

Addressing the climate crisis is going to demand a heavy dose of government intervention in the economy. But it will require more than that. A carbon tax will deliver economy-wide impact, giving every business and household incentives to change how they produce things and what things they buy. Getting the job done will take billions of dollars in public investments and millions of smaller decisions in the marketplace. A carbon tax will make more of the latter happen.

3. A carbon tax can affect industries that are hard to regulate.

There’s no question that performance standards and other regulations must be a major part of climate policy. But not everything lends itself to such regulation. As energy analyst Hal Harvey explained to Vox’s David Roberts late last year:

It’s hard to set a performance standard that works for glass, pulp and paper, steel, chemicals, and so forth. So in those realms, setting a price is a nice way to handle it. Then businesses can simply internalize the costs and make better decisions.

4. A carbon tax makes everything else we need to do easier.

Want to subsidize renewables? Higher fossil fuel prices will allow smaller subsidies to close the cost gap between carbon-based and renewable power. The same amount of spending on subsidies will then bring more renewables online.

Want to incentivize clean energy investments, like energy efficiency? Higher fossil fuel prices shorten the payback period on those investments. Again, we’ll be able to reduce the degree of subsidies or other inducements required to get households and businesses to make those investments.

Carbon taxes can even replace some regulatory efforts. Citizens’ Climate Lobby argues that its fee-and-dividend proposal could reduce emissions in the power sector more and faster than President Obama’s Clean Power Plan proposal. That means regulatory efforts could concentrate instead on sectors, like transportation and buildings, that are less responsive to energy pricing signals than power generation.

5. A carbon tax can affect emissions beyond our borders.

It’s not enough to reduce U.S. emissions. The rest of the world must do its part. (Of course, right now the rest of the world is saying that about us.) A carbon tax with a border adjustment can pressure other countries to impose their own robust carbon pricing measures. The border adjustment adds a fee to imports tied to the level of carbon emissions required to make that product. (This is, admittedly, not an easy thing to do. Adele Morris of The Brookings Institution treats the complications in a policy brief.)

The border adjustment would be waived on imports coming from countries with carbon pricing equivalent to ours. Each country would face a choice: Pay the U.S. a border adjustment on your exports, or pay yourself the equivalent amount via a carbon tax. For countries that export to the U.S. market, that shouldn’t be a hard decision.

6. A carbon tax will raise revenue that can be used for other climate mitigation programs.

A Green New Deal will create lots of jobs primarily by spending lots of money — rebuilding the power grid, subsidizing clean energy, retrofitting buildings, redesigning cities to be less automobile-dependent, creating an infrastructure to recharge electric cars, etc. That money comes from somewhere, and a carbon tax is a logical source of funds — especially a robust tax that would, in the out years, bring in hundreds of billions of dollars per year.

This is only half an argument for a carbon tax, however, because there are reasons based in economic justice to use the revenue differently. Any carbon tax will hit low-income households proportionally harder than high-income ones, and some or all of the revenue ought to be used to offset the tax’s regressive effects. Fortunately, there are many progressive funding streams — including taxes aimed at high incomes, wealth, or financial transactions — for raising the revenue to fund a Green New Deal. But if the only politically practical way to pay for a Green New Deal requires some carbon tax revenue, the revenue will be there.

* * *

A carbon tax was never an easy sell on its own, and it won’t be an easy sell as part of a Green New Deal either. David Leonhardt at The New York Times just posted a good history of its difficult political fortunes, and comes down about where we are:

The better bet seems to be an “all of the above” approach: Organize a climate movement around meaningful policies with a reasonable chance of near-term success, but don’t abandon the hope of carbon pricing. Most climate activists, including those skeptical of a carbon tax, agree about this.

Carbon tax advocates should take this call to heart. Even with a Democratic takeover in 2020 — which is no sure thing — the U.S. is some years away from either a Green New Deal or a carbon tax. We should use that time to make sure the ultimate answer is “both.”

Here’s how we calculated our figures in the first numbered paragraph: CTC’s carbon-tax spreadsheet model (downloadable Excel file) puts U.S. CO2 emissions from fossil fuels at 5,409 million metric tons (MMT) in 2010 and 4,992 MMT in 2017. With Rhodium’s 3.4% one-year increase, emissions were 5,162 MMT in 2018. To cut that to 2,704 MMT (half of 2010 emissions) in 2030 requires a 5.2 percent annual drop (calculated by exponentiating 2704/5409 to the 1/12 power – 12 years – which is 0.948). A similar calculation from 2005 emissions of 5,822 MMT to the 2017 figure of 4,992 MMT yields an average annual drop of 1.3% over those 12 years.

These considerations appear to have finally pushed New York’s Mayor Bill de Blasio off the political fence last month to

These considerations appear to have finally pushed New York’s Mayor Bill de Blasio off the political fence last month to

The Green New Deal means many things to many people, but the unifying concept is to position climate change mitigation as a retooling of the U.S. economy, particularly our infrastructure, with massive green investment and millions of green jobs. The closest thing to an official statement of purpose is

The Green New Deal means many things to many people, but the unifying concept is to position climate change mitigation as a retooling of the U.S. economy, particularly our infrastructure, with massive green investment and millions of green jobs. The closest thing to an official statement of purpose is

Indeed, it may have been precisely the failure to consider the broader social equity context that doomed France’s recent fossil fuel surcharge at the hands of the Yellow Vests — many of whom

Indeed, it may have been precisely the failure to consider the broader social equity context that doomed France’s recent fossil fuel surcharge at the hands of the Yellow Vests — many of whom