February 8, 2017, 9:30 a.m. • For Immediate Release

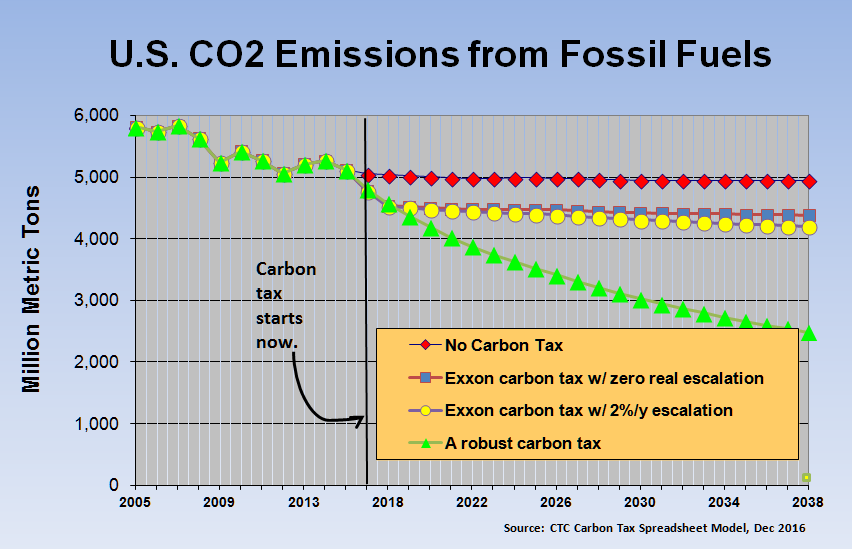

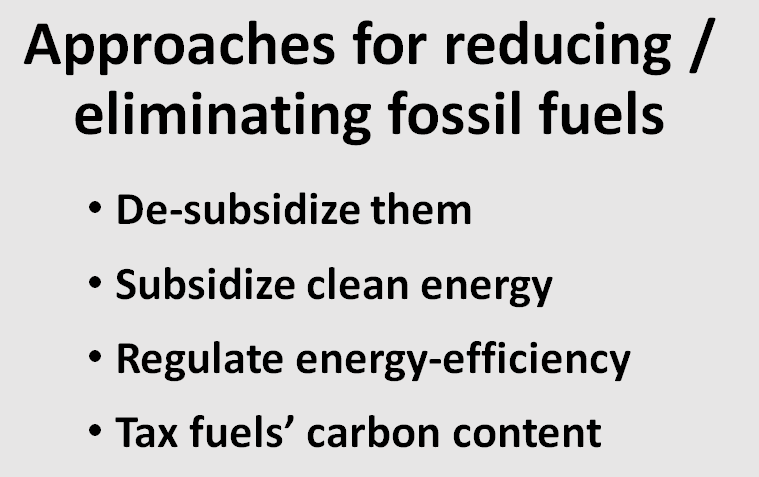

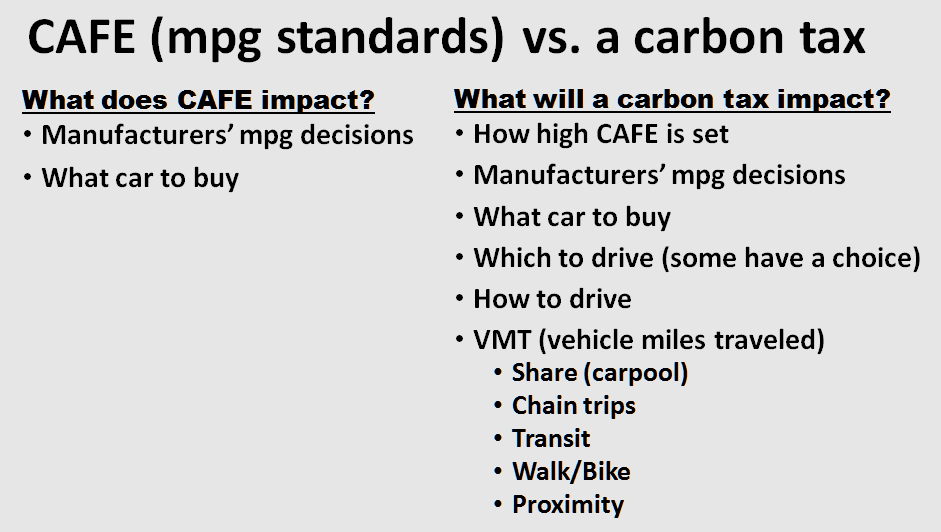

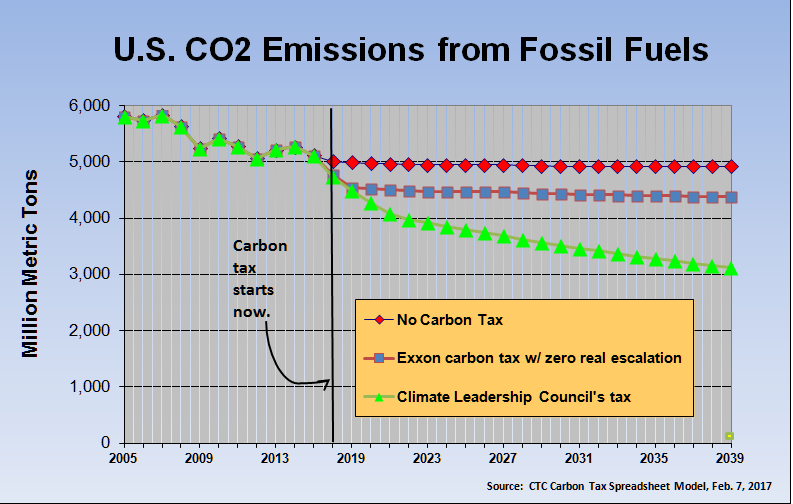

The Carbon Tax Center voiced strong support this morning for a proposal by the Climate Leadership Council to enact a comprehensive nationwide carbon tax starting at $40 per ton of carbon dioxide and rising over time.

The Council is scheduled to release its proposal, “The Conservative Case for Carbon Dividends,” at the National Press Club this morning, Wednesday, Feb. 8, at 9:30 a.m.

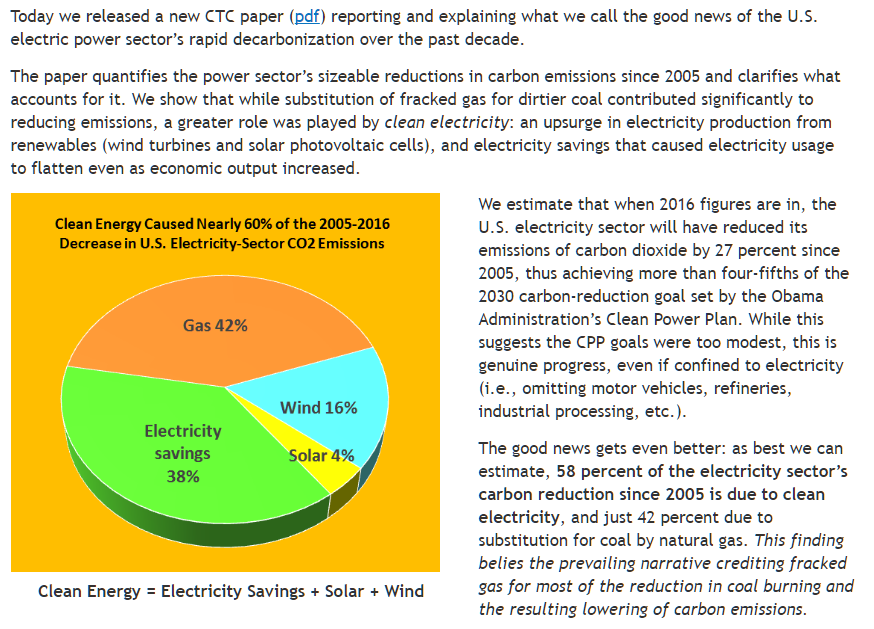

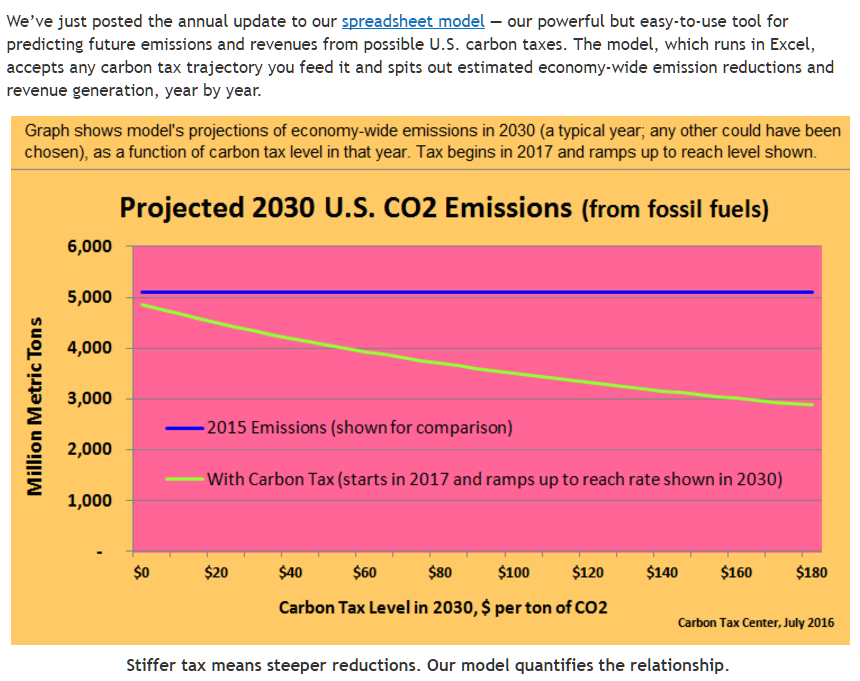

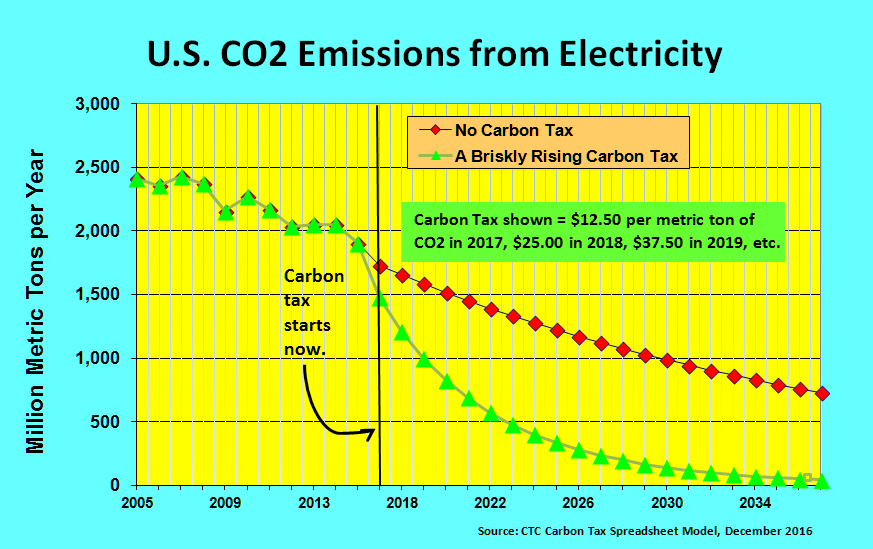

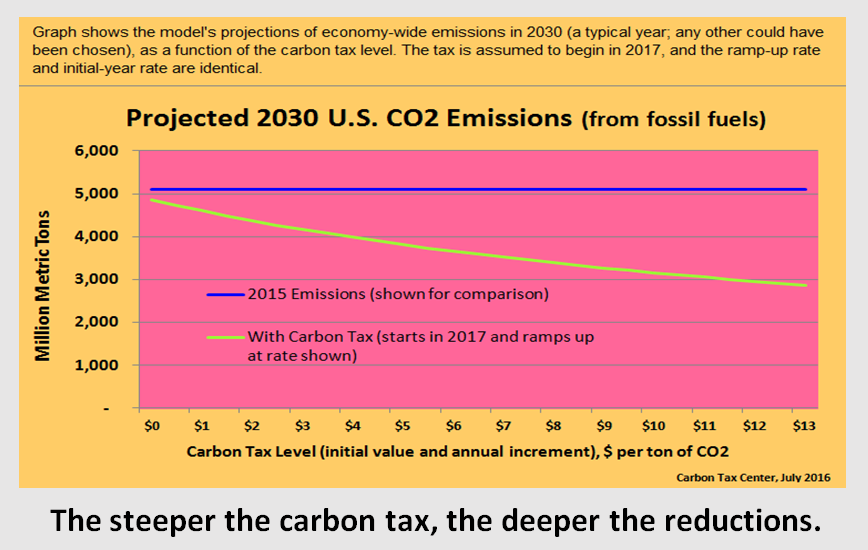

Modeling by the Carbon Tax Center suggests that a $40/ton carbon tax starting in 2018 and rising by $5/ton each year would, by 2030, reduce U.S. emissions by 2.3 billion metric tons from 2005 level.

A $40 per ton tax on carbon pollution starting in 2018 and rising thereafter by $5 per ton each year would, by 2030, reduce annual U.S. CO2 emissions from levels in 2005 (a common baseline year) by an estimated 2.3 billion metric tons, a 40 percent reduction.

Alternatively, measured against a moving “business as usual” trajectory with no national carbon price, the 2030 reductions would be 1.4 billion metric tons a year, or nearly 30 percent of unpriced emissions projected for that year.

(The Council’s proposal envisions that “A sensible carbon tax might begin at $40 a ton and increase steadily over time.” We chose $5/ton as a politically palatable annual rate of increase, and modeled such a tax using our carbon tax model.)

“The robust carbon tax proposed by the Climate Leadership Council would vault the U.S. from the middle to the head of the global pack in reducing heat-trapping, climate-damaging emissions,” said Carbon Tax Center director Charles Komanoff. “It would also provide a template for other nations to follow, creating a real possibility of keeping the rise in global temperatures to 2 degrees Centigrade or less,” Komanoff said.

Using CTC’s model, Komanoff calculated that the future emissions reduction rate with the Council’s carbon tax would surpass by 50 percent the actual reduction rate since 2005, “a major achievement,” he said, “given that the past reductions were largely enabled by eliminating much coal-burning – the lowest-hanging fruit in eliminating carbon.”

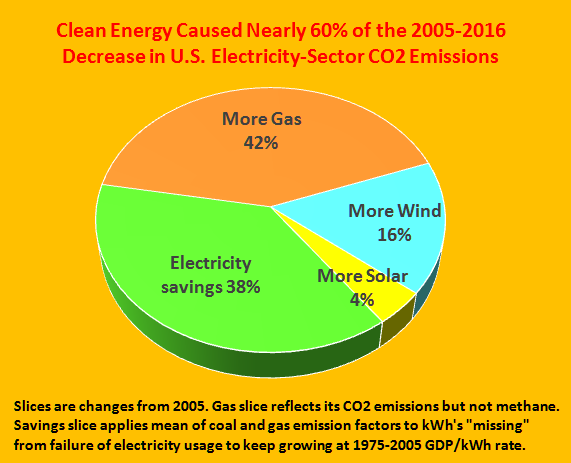

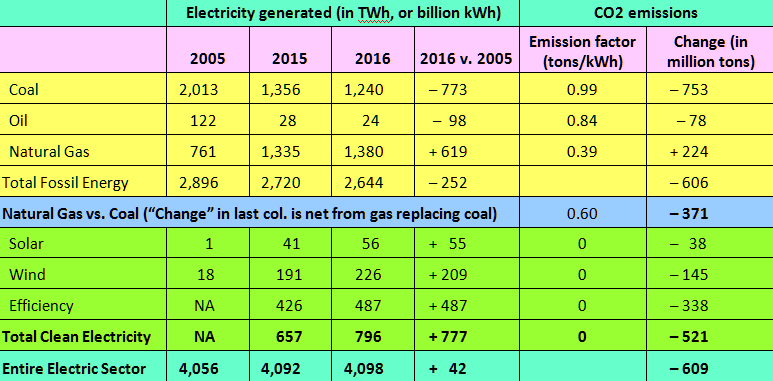

CTC also endorsed the political “swap” in the Council’s proposal to rescind the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan. “The important work of the Clean Power Plan was largely completed anyway,” said Komanoff, pointing out that well over 80 percent of the plan’s targeted reduction in electricity-sector emissions for 2030 had already been achieved by the end of 2016. “The proposed carbon tax is the logical and necessary next step,” he said, “instilling incentives throughout the U.S. economy to replace fossil fuels with clean energy.”

CTC further endorsed the Council’s proposal to “dividend” the carbon tax revenues to U.S. households on a quarterly basis. “We’ve studied ‘fee-and-dividend’ for years, and can vouch that it’s the most equitable, least bureaucratic and least corruptible way to distribute the hundreds of billions of dollars of revenue from a carbon tax, while also generating jobs,” Komanoff said.

Komanoff sounded a cautionary note about the dogged resistance of Congressional Republicans to climate action, but added that the Council’s proposal hits all the right marks for a business-friendly, small-government climate policy. “Republicans looking for a way out of their denialist, obstructionist stance on climate have been handed a lifeline,” he said. “Their children and grandchildren are counting on them.”

# # # # # # # #

About CTC: Since 2007, the Carbon Tax Center has stood at the front lines of the struggle for a sustainable climate and a habitable Earth. Our mission: to generate support to enact a transparent and equitable U.S. carbon pollution tax as quickly as possible — one that rises briskly enough to catalyze virtual elimination of U.S. fossil fuel use within several decades and provides a template and impetus for other nations to follow suit.

Erik had a

Erik had a