Why do Copenhageners ride bicycles? The key reason, says Yale economist and best-selling author (“Irrational Exuberance”) Robert J. Shiller, is that Danes are idealists who resolved, after the oil crisis of the 1970s, “to make a personal commitment to ride bicycles rather than drive, out of moral principle, even if that was inconvenient for them.”

“The sight of so many others riding bikes motivated the city’s inhabitants and appears to have improved the moral atmosphere enough,” Shiller wrote in yesterday’s New York Times, that the share of working inhabitants of Copenhagen who bike has reached 50 percent.

In much the same way, Shiller argues, “asking people to volunteer to save our climate by taking many small, individual actions” may be a more effective way to bring down carbon emissions than trying to enact overarching national or global policies such as carbon emission caps or taxes.

Goodness. Rarely do smart people so badly mangle both the historical record and basic economics. I say “people” because Shiller attributes his column’s main points to a new book, “Climate Shock: The Economic Consequences of a Hotter Planet” by Gernot Wagner of the Environmental Defense Fund and Martin L. Weitzman, a Harvard economist. And I say “smart” because the three stand at the top of their profession. Shiller won the Economics Nobel in 2013, Weitzman is a leading light in the economics of climate change, and Wagner is highly regarded young economist.

But mangle they have (I haven’t seen the Wagner-Weitzman book but assume that Shiller represents it fairly).

Let’s start with the history, which is fairly well known to anyone versed in cycling advocacy, as I’ve been since the 1980s, when I spearheaded the revival of New York City’s bike-advocacy group Transportation Alternatives (as recounted here.) Copenhagen’s 40-year bicycle upsurge, and indeed much of the uptake of cycling across Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands, came about not through mass idealism but from deliberate public policies to help cities avoid the damages of pervasive automobile use while reducing oil dependence.

If idealism played a part at the outset it was a social idealism that instructed government to undertake integrated policies ― stiff gas taxes and car ownership fees; generously funded public transit; elimination of free curbside parking; provision of safe and abundant bicycle routes ― that enabled Copenhageners to do what they evidently desired all along: to use bikes safely and naturally.

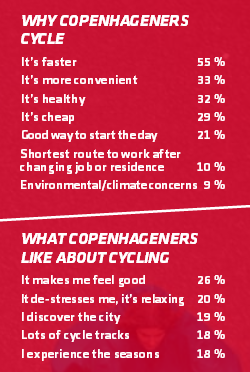

The telltale is in the graphic. Only one in eleven Copenhageners who cycle have environment and climate in mind. The majority do it because it’s faster than other ways to travel, and around a third of cyclists say they ride because it’s healthy, inexpensive and convenient ― belying Shiller’s meme of Danes idealistically choosing bikes despite their inconvenience vis-à-vis cars. (more…)