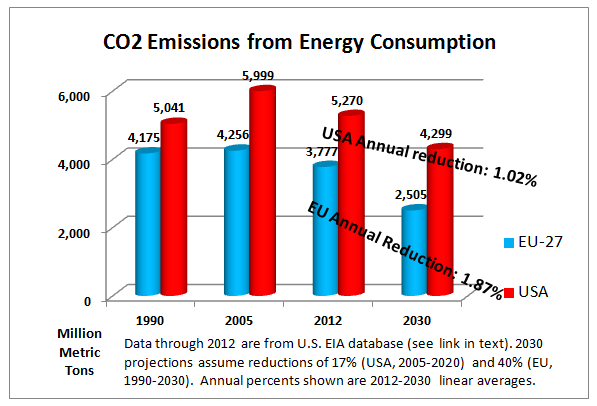

The European Union announced last week its intention to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases by 40% from 1990 levels by 2030. Meanwhile, the U.S. goal remains a 17% emissions cut from 2005 levels, by 2020.

Two different percentages over two different time periods. How do the EU and U.S. trajectories compare? Is the EU’s use of a 1990 baseline cheapening its goal, as some have suggested?

No, it turns out. As the graphic shows, the 27 countries making up the European Union generated slightly less CO2 in the EU’s baseline year of 1990 than in the 2005 baseline chosen by United States authorities. More importantly, after running a few numbers, we can safely report that the EU emissions objective embodies nearly twice as high a reduction rate to 2030 from 2012 (the most recent year with comparable data) as the US target: an average annual decline in emissions of 1.87% for the EU, vs. 1.02% for the United States. (more…)

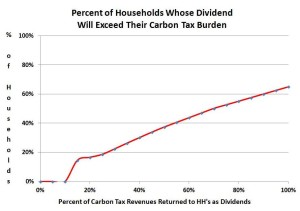

![A revenue-neutral carbon tax, in which all tax revenue would be returned to the public as a rebate check ["dividend"], receives 56% support. The largest gains in support [relative to opinion on a carbon tax w/o revenue mention] come from Republicans.](https://www.carbontax.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Franklin-C-Note-_-reviewme23-_-flickr-_-downloaded-22-July-2014-300x125.jpg)