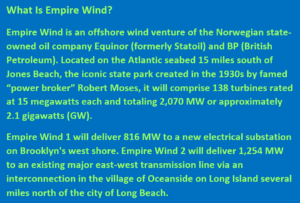

NY Gov. Kathy Hochul last month vetoed a bill that could have expedited a huge wind farm in the Atlantic Ocean off Long Island. Her veto imperils not just the project, called Empire Wind, but New York State’s hopes to decarbonize its electric grid and validate its claim to national climate leadership.

I’ll argue here that a state or federal carbon price — one more substantial than the relative pittance of $15 per ton now being charged for electricity sector emissions under the RGGI compact — could have helped the developers beat back the NIMBYs whose rabble-rousing helped force Hochul’s hand. Let’s review the project and then explain how its difficulties are connected to the absence of robust carbon pricing.

Empire Wind Will Be Large

There will be 138 turbines, identical and gigantic. At 387 feet, each turbine blade will be the length of a football field including the end zones. The distance from water surface to blade tip at full height will be 886 feet, roughly the extent of two celebrated Manhattan towers that a century ago were the world’s tallest buildings: the 792-foot Woolworth Building (#1 from 1913 to 1930) and the 1,046-foot Chrysler Building (1930-1931). An even funner fact, from the developer’s spec sheet, is this: just one complete rotation by one turbine’s three blades will “power a New York home for about 1.5 days.”

There will be 138 turbines, identical and gigantic. At 387 feet, each turbine blade will be the length of a football field including the end zones. The distance from water surface to blade tip at full height will be 886 feet, roughly the extent of two celebrated Manhattan towers that a century ago were the world’s tallest buildings: the 792-foot Woolworth Building (#1 from 1913 to 1930) and the 1,046-foot Chrysler Building (1930-1931). An even funner fact, from the developer’s spec sheet, is this: just one complete rotation by one turbine’s three blades will “power a New York home for about 1.5 days.”

The anticipated annual electrical generation from Empire Wind 1 and 2 combined is 7.25 TWh (or, if it’s easier, 7,250,000,000 kilowatt-hours),assuming a 40% yearly capacity factor. Here are four alternative ways of visualizing the significance of that output:

- Empire Wind’s 7.25 TWh is half again as great (i.e., 1.5x as large) as the entire production by New York State wind turbines in 2022 (that figure was 4.8 TWh);

- 7.25 TWh is 5 to 6 percent as great as all electricity generated from all state sources in 2022 (130.5 TWh);

- 7.25 TWh is one-sixtieth (1/60) as much as all U.S. wind-generated electricity last year (435 TWh), a figure that itself constituted a tenth of U.S. electricity production from all sources;

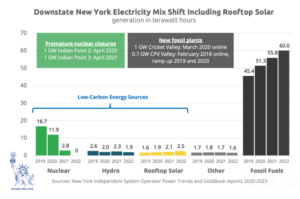

- 7.25 TWh is close to (12 percent less than) the average annual 2010-2019 output of either of the twin Indian Point reactors in suburban Westchester County that until their recent forced retirement were downstate New York’s lone large-scale source of carbon-free electricity. (The entire Indian Point station’s average annual output over its final decade, 2010-2019, was 16.5 TWh.)

Putting aside that last benchmark — which is intended as a reminder of the carbon disaster of shutting Indian Point (and a cautionary tale against shutting its West Coast doppelganger, Diablo Canyon) — Empire Wind looms large in New York state’s goal of attaining a 70 percent carbon-free grid in 2030.

The state’s 2022 carbon-free electricity share was just 48 to 49 percent, down from 60 percent in 2019, before Indian Point’s closure commenced. If Empire Wind’s output were available today, the statewide share would stand at 54 percent, indicating that this single (albeit two-part) project can close a quarter of the gap from the current clean percentage to the 2030 target.

Hochul and the NIMBYs

Along with infusing the grid with billions of clean kilowatt-hours, building and servicing Empire Wind 1 and 2 is expected to create 1,300 permanent onshore jobs — 300 to manufacture turbine components at the Port of Albany, and 1,000 in operation and maintenance at the South Brooklyn Marine Terminal, according to Equinor, the developer. These numbers, along with the clean electricity, ought to be catnip for any Democratic politician.

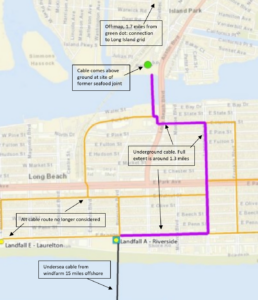

Why, then, did Hochul on Oct. 20 veto a bill that could have cleared the path for the Empire Wind 2 power cable to run under Long Beach and connect to the electric grid in Oceanside?

There’s no shortage of possible rationales. Long Island flipped from shaky blue to all red a year ago, as Democrats lost all four Congressional races and a number of state legislative seats while Hochul herself was outvoted there in her unnervingly close re-election. She may be seeking to preserve political capital for a possible renewed push to undo exclusionary zoning that that keeps housing in Nassau and Suffolk counties unaffordable for newcomers or those without generational wealth. Moreover, Empire Wind itself has faced financial headwinds due to supposed supply chain bottlenecks and spiraling financing costs, with the latter due in no small part to the regulatory delays.

Whatever the reasons, Hochul went all NIMBY-friendly. Her veto message faulted Equinor for running roughshod over Long Beach residents (see pull quote at left) rather than calling out the obstructionists for teeing up a replay of 2012’s Superstorm Sandy that devastated the very communities that now are clamoring for the wind project to go away.

In her message, the governor ignored the tinfoil-hat essence of most anti-wind opposition, which one observer, a former New York City chief climate policy advisor, characterized as combining “propaganda from the fossil fuel industry, rumor mongering in local communities, and basic nimbyism.” As NY Focus helpfully reported in Long Island Politicians Claim Victory for Hochul Wind Power Veto, objections to the Empire Wind farm and cables run the gamut from shopworn (ocean views sullied by turbines 15 miles offshore) to debunked (health-harming electromagnetic radiation from the power cables) to chronologically impaired (“We’ve had a huge number of [dead] whales that are showing up on our beaches,” a state senator fretted, yet not even a single offshore wind turbine has begun operating on the Atlantic Coast).

Entire cable route through Long Beach is underground. Yet NIMBYs are holding hostage a not-quite-in-their-backyard project that would more than double NY wind power production. Incidentally, I was born and grew up in a house on Washington Blvd, just a few blocks past the left edge of the map. Equinor map adapted by CTC.

Hochul and her staff seem unaware that there is no placating NIMBYs, whether their sights are trained on giant offshore wind projects or small-bore items like transit-friendly higher-rise housing or bike lanes. To the naysayers, any palpable change in their way of life is either Armageddon in itself or a pathway to purgatory. The only way to deal with them is to give pro-development, pro-change forces the strength to vanquish the NIMBYs outright — which is where carbon pricing comes in.

Would You Like $240 Million in (Annual) Carbon Benefits With Your Order?

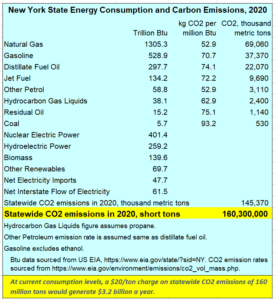

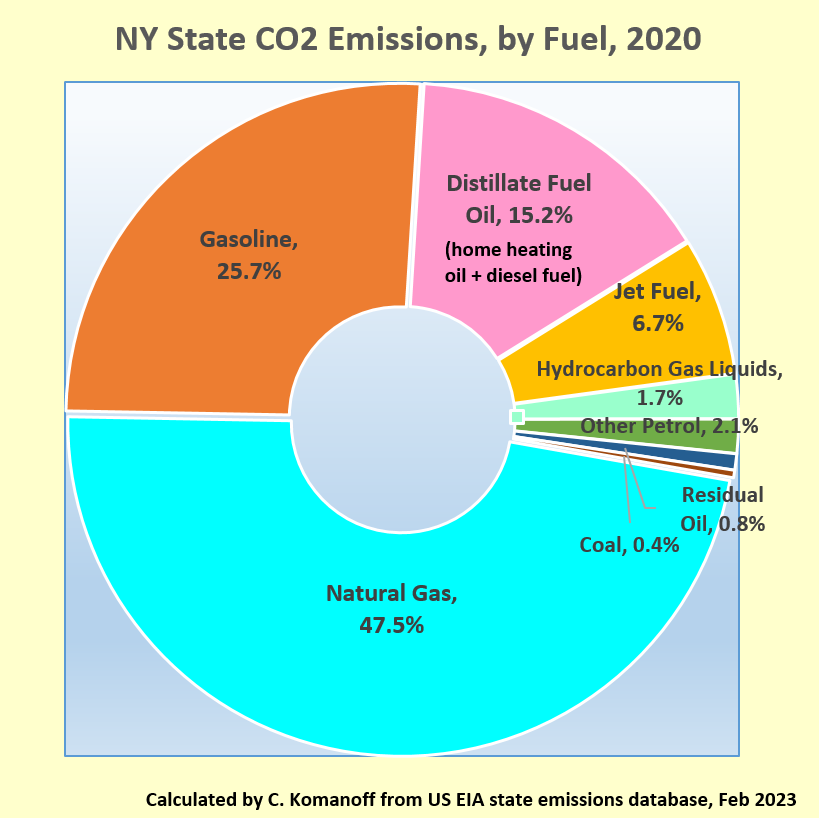

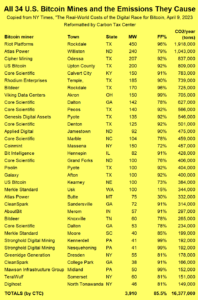

Offshore wind’s chief virtue — in some respects, its true raison d’être — is its ability to take the place of dirty, fossil-fuel electricity generation in the grid. This asset is particularly salient in the case of Empire Wind, insofar as the downstate New York grid, with only modest interconnections to greener grids upstate or elsewhere, obtains more than 90 percent of its annual electricity by burning methane (“natural”) gas.

As a result, nearly every kilowatt-hour from Empire Wind will directly displace a kWh from burning fracked gas. And though the 90% share will decline when the new Champlain-Hudson Power Express transmission line enters service, perhaps in 2026, nearly all of the “incremental,” hour-by-hour power production actually avoided by generation from Empire Wind will still be gas-fired when the project’s two parts come on line in 2028 and 2029.

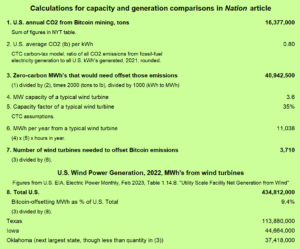

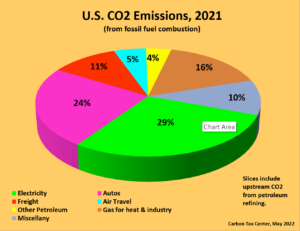

Now picture a federal or state carbon tax — or “price” if you prefer. Set it at $100 per metric ton (“tonne”) of CO2, which is both a round number and the level the Carbon Tax Center has been advocating since our inception, to be reached after a ramp-up taking half-a-dozen years. Now apply the carbon tax to the CO2 emitted from one kWh generated by burning gas. You’ll find that the carbon tax associated with each such kilowatt-hour is 3.9 cents.

Calculations: 659 x 10^6 tonnes (CO2 emissions from 2022 U.S. gas-fired electricity) divided by 1.689 x 10^12 kWh (U.S. electricity generated with gas in 2022) multiplied by 10^4 ¢ charged per tonne yields 3.90¢/kWh.

Let’s bring that figure down to earth: With a $100/ton (okay, tonne) carbon tax, each gas-fired kWh in competition with Empire’s offshore wind would cost 3.9 cents more to generate than at present. (To keep the discussion simple, I’ve refrained from counting an additional tax on methane.) We trim that to 3.3¢/kWh because the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) already charges a carbon price on fuels used to generate electricity in New York and neighboring states; in the most recent (September) quarterly auction, that price reached $13.85 per short ton, equivalent to $15.25 per metric ton, which we deduct from our aspirational $100/tonne carbon price to avoid double-counting, reducing it by just over 15 percent.

The hypothetical 3.3¢/kWh additional carbon charge for gas-generated electricity (stemming from the $100 carbon price) multiplied by Empire Wind’s 7.25 TWh annual output yields $240 million per year. Those dollars represent a first estimate of the additional annual revenue Equinor could have sought in its 2018 and 2020 bids responding to NYSERDA’s solicitations to prospective developers of offshore wind projects. (See text box further below.) With a robust NY carbon price, in other words, Equinor’s Empire Wind venture would enjoy a far higher profit margin.

Offshore Wind’s Missing Carbon Price

Imagine what Equinor might have done with $240 million a year in additional Empire Wind revenue. It could have banked, say, half that amount to offset the price escalation and higher interest costs that this year lowered its prospective profit margins and compelled it to appeal to NY State to grant a higher price for its production. (Incidentally, the NY Public Service Commission’s Oct. 12 order denying Equinor’s petition seeking renegotiation of its power contract with NYSERDA provides a good capsule summary of NY state offshore wind activity; it can be found via this link; search for Cases 15-E-0302 and 18-E-0071.)

The other $120 million, or a good chunk of it, could have been used — and might still be — to provide economic benefits to Long Beach and other communities that consider themselves “affected” by Empire Wind’s turbines or cables.

Empire Wind website paragraph about Taxes makes no mention of payments — voluntary or mandatory — to Long Beach and other communities.

As a thought-experiment, consider that $120 million distributed equally to Long Beach’s 11,700 households (assuming the city’s 35k population resides 3 per household) could provide recurring yearly dividends of around $10,000 per household, once the electricity began to flow. Perhaps more practical would be to set aside $75 million as a one-time payment to retire the so-called Haberman Judgment holding Long Beach financially responsible for blocking a proposed real-estate venture near the boardwalk and ocean beach several decades ago (see City of Long Beach 2023-2024 adopted budget, pages ii-iii).

Of course there are any number of other “improvements” that Long Beach, Island Park and Oceanside might elect to be funded by Equinor “payments in lieu of taxes.” I was surprised that Empire Wind’s online materials do not mention any such payments.

The idea is not to “win over” the NIMBYs — I consider that a fool’s errand — but to neutralize and politically overpower them by appealing to the larger community’s enlightened self-interest. Not so much the members of the Long Beach city council — who apparently (and astoundingly) went from 5-0 in favor of permitting the cable route to 0-5 between spring and fall of 2023 — but the citizenry that holds sway over them.

This isn’t my first time linking carbon pricing to big, hence potentially intrusive, green-energy projects. I struck that note in 2006, in Whither Wind, a long-form piece on wind and other green power for Orion magazine:

[I]if carbon fuels were taxed for their damage to the climate, wind power’s profit margins would widen, and surrounding communities could extract bigger tax revenues from wind farms. Then some of that bread upon the waters would indeed come back — in the form of a new high school, or land acquired for a nature preserve.

The urgency now is far greater. Today, as I was wrapping this post, the New York Times reported that the Danish offshore wind company Orsted canceled an equally large (2248 megawatts) wind farm, Ocean Wind 1 and 2, it was developing off New Jersey’s Atlantic coast. Orsted cited the same combination of faltering economics and local opposition (which of course weakens the economics further through delays) now besetting Equinor and Empire Wind. Note too that even though Empire Wind 1’s interconnection to the grid, also under the seabed but through Brooklyn, is not (now) threatened, the economics will almost certainly kill Part 1 if Empire Wind 2 through Long Beach goes down.

The urgency now is far greater. Today, as I was wrapping this post, the New York Times reported that the Danish offshore wind company Orsted canceled an equally large (2248 megawatts) wind farm, Ocean Wind 1 and 2, it was developing off New Jersey’s Atlantic coast. Orsted cited the same combination of faltering economics and local opposition (which of course weakens the economics further through delays) now besetting Equinor and Empire Wind. Note too that even though Empire Wind 1’s interconnection to the grid, also under the seabed but through Brooklyn, is not (now) threatened, the economics will almost certainly kill Part 1 if Empire Wind 2 through Long Beach goes down.

Long-time CTC followers will recall my standing frustration over wind and solar entrepreneurs’ lack of interest in pushing carbon pricing. Efficiency gains, cost reductions and the magical appeal of green power would carry them over any and every threshold, they imagined. Will today’s NJ offshore wind defeat and the one looming in NY be enough to convince clean-power developers that they need a carbon tax every bit as much as the climate does?

This post, written by renowned eco-journalist Christopher Ketcham and commissioned by and

This post, written by renowned eco-journalist Christopher Ketcham and commissioned by and

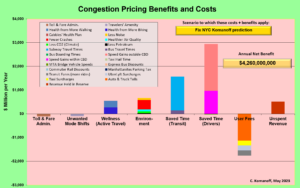

That huge sigh of relief from New York City mass transit advocates last weekend was for the state budget handshake to tack more than a billion additional dollars a year onto a key MTA funding stream, the Payroll Mobility Tax. According to both my calculations and

That huge sigh of relief from New York City mass transit advocates last weekend was for the state budget handshake to tack more than a billion additional dollars a year onto a key MTA funding stream, the Payroll Mobility Tax. According to both my calculations and  Dedicating a third of those proceeds to the MTA would add a billion dollars to the authority’s annual revenue. Other slices of the revenue could cure deficits at smaller transit systems around the state.

Dedicating a third of those proceeds to the MTA would add a billion dollars to the authority’s annual revenue. Other slices of the revenue could cure deficits at smaller transit systems around the state. RGGI currently charges electricity producers around $14 for each ton of CO2 their generators emit. This levy is generating

RGGI currently charges electricity producers around $14 for each ton of CO2 their generators emit. This levy is generating

But it would not be extinguished. That’s where the climate movement comes in.

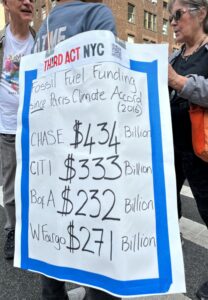

But it would not be extinguished. That’s where the climate movement comes in. The bank protests seem even less focused. Conoco doesn’t need financing from JPMorgan Chase or Wells Fargo to

The bank protests seem even less focused. Conoco doesn’t need financing from JPMorgan Chase or Wells Fargo to

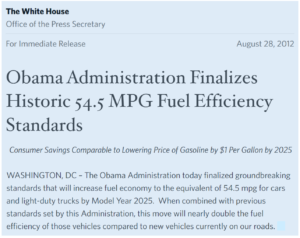

The supposed impossibility of reducing the use of gasoline by raising its price has been part and parcel of Big Green’s attachment to mpg standards — despite the fact that mileage reg’s do nothing to reduce driving and its vast negative consequences: not just traffic congestion but also poor health (sedentary living, car crashes, noise) and general unaffordability (car loan costs, upkeep expenses, costlier housing due to cars’ consuming urban and suburban land).

The supposed impossibility of reducing the use of gasoline by raising its price has been part and parcel of Big Green’s attachment to mpg standards — despite the fact that mileage reg’s do nothing to reduce driving and its vast negative consequences: not just traffic congestion but also poor health (sedentary living, car crashes, noise) and general unaffordability (car loan costs, upkeep expenses, costlier housing due to cars’ consuming urban and suburban land).