While the world is abuzz with the news that a fusion laboratory in California recently generated more energy than the reaction consumed, a different breakthrough in Europe may portend bigger, faster progress on carbon emissions and climate: European national governments and the European Parliament have reached an agreement to tax imported goods and materials based on the carbon dioxide emitted in making them.

The levies will initially apply to imports of iron and steel, cement, aluminium, fertilizers, hydrogen and electricity, according to Euractiv, the Brussels-based pan-European news site specializing in EU matters, which also reported that the mechanism “will mirror the EU’s own domestic carbon price.”

That price — the price of emissions allowances traded on the European Union’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) — on Dec. 1 was 85 euros per metric ton, equivalent to around $91 per metric ton, or nearly $83 per short (U.S.) ton, a far higher price than the starting levies embodied in most U.S. carbon tax proposals. If “mirrors” means “duplicates,” imports from non-carbon-taxing countries may soon face steep charges indeed.

English translation: For the climate, as Europeans, we are constantly taking action. The European Union today adopted a carbon border tax. Our requirement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions will thus apply to the products we import. We are going forward!

With the agreement, which caps more than a year of negotiations, the European Union is poised to “insert climate-change regulation for the first time into the rules of global trade,” the Wall Street Journal noted. Pascal Canfin, chair of the European Parliament’s Environment Committee, was even more emphatic, telling the New York Times that “We are putting carbon and climate at the heart of trade.”

The Journal added that “The plan, known as the carbon border adjustment mechanism, would be the world’s first tax on the carbon content of imported goods.”

CBAM could become a breakthrough

What could make the EU agreement a climate breakthrough is the tantalizing possibility that carbon border adjustment mechanisms (CBAMs) may compel the United States, China and other major emitters to finally enact national carbon taxes or equivalent carbon-pricing mechanisms.

The initial step in this scenario, which the Journal says “the EU is expected to adopt in the coming weeks as part of a sweeping package of legislation [to] step up the bloc’s efforts to limit global warming,” is to tax imports of key industrial commodities like steel, aluminum and cement to the extent that the carbon intensity of their manufacture exceeds EU averages. Exporters then have two ways to avert the trade tax. They can cut down on the carbon emitted to produce their product. Or the country in which they produced it can tax carbon emissions to the same level as the EU’s carbon price.

The climate wins either way. The first way directly cuts emissions in the industrial sectors covered by the tax. The second cuts emissions indirectly, but far more broadly, via the carbon tax’s economy-wide incentives that steer all energy supply and demand away from fossil fuels by making the market prices for coal, oil and gas reflect at least some of their climate damage.

The announcement from Europe follows by less than a week the Biden administration’s transmission to the EU of a proposal suggesting “creation of an international consortium that would promote trade in metals produced with less carbon emissions, while imposing tariffs on steel and aluminum from China and elsewhere,” according to the New York Times.

While the Biden proposal is merely a “concept paper” and is being kept under wraps, the Office of the United States Trade Representative, which drafted it, has at least given it a name — the Global Arrangement on Sustainable Steel and Aluminum. The Times story called it “the first concrete look at a new type of trade arrangement that the Biden administration views as a cornerstone of its approach to trade policy … one [that] would wield the power of American and European markets to try to bolster domestic industries in a way that also mitigated climate change.”

The trade concept paper appears to embody the principles underlying the Clean Competition Act (S. 4355) introduced in June by U.S. Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI), perhaps Congress’s most indefatigable climate hawk, to tax both domestic and foreign manufacturers of steel, aluminum, cement and other industrial commodities to the extent that the carbon intensity of their manufacture exceeds U.S. averages.

(A July post here by CTC contributor Mike Aucott, A Novel Way to Price Industrial Carbon Emissions?,” has terrific details on how CBAMs would look from a U.S. perspective, and includes a link to a comprehensive report by the Climate Leadership Council on the relative carbon advantage of U.S. industry compared to Russia, China and the authoritarian petro-states. In a similar vein is a September report from Resources for the Future that compiles carbon emission intensities of both domestic and foreign producers for 39 industrial sectors.)

As for nuclear fusion …

National Ignition Facility, seen from above. Its huge scale is indicated by three helmeted workers near foreground. Photo courtesy of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, National Ignition Facility & Photon Science.

We’re thrilled that on Dec. 5, the National Ignition Facility in Livermore, CA achieved an historic first in efforts to harness nuclear fusion, when their laser-driven fusion device, in a brief (100 trillionths of a second) burst, achieved “positive net energy” by generating a flow of neutrons carrying 3 megajoules of energy, exceeding by almost 50 percent the 2.05 megajoules the lasers consumed in the process, as New York Times science correspondent Kenneth Chang reported yesterday.

That’s terrific news for science and, maybe someday, human prosperity and global sustainability. It’s been a long time coming.

We’ve been reading, and dreaming, about the wonders of fusion power — seemingly low and short-lived radioactivity, impossibility of runaway reactions or meltdowns, abundant resource base (deuterium and tritium in seawater), and of course carbon-free — since the 1960s.

But for almost as long, we’ve been mindful of the dauntingly high hurdles that nuclear fusion must clear to ever operate on a commercial, global scale. As climate activist and author Bill McKibben usefully pointed out this week, “producing [the Livermore Lab] reaction required one of the largest lasers in the world.” Not only that, “the reaction creates neutrons that can destroy the very equipment required to produce it” through chronic embrittlement.

Amplifying those concerns, Arthur Turrell, deputy director for research and economics at the U.K.’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) Data Science Campus, and author of The Star Builders: Nuclear Fusion and the Race to Power the Planet, reminded listeners on the Brian Lehrer Show yesterday that for the Livermore Lab breakthrough to lead to the advent of commercial, global-scale electricity, it must be miniaturized and also made modular and scalable.

Perhaps this can happen someday, with enough time, money and commitment. But the march to that point will be measured not in years but in many — multiple — decades.

Consider that a quarter-century elapsed from the first sustained fission chain reaction at the University of Chicago, in 1942, to New Year’s Day 1968, when the first non-prototype nuclear power plants in the United States, Connecticut Yankee and San Onofre 1 (around 500 megawatts each), achieved commercial operation. And harnessing nuclear fission was a far simpler task than achieving breakeven with nuclear fusion, judging by the multiple order-of-magnitude scale differences between Enrico Fermi’s fission team — which operated in a confined space beneath the college football stadium! — and the enormous National Ignition Facility shown in the photograph.

Clearly, it would be folly to ease up on the multiple, synergistic programs to move the U.S. and the rest of the world off of fossil fuels, including implementing the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 and progressing with carbon pricing. As Stephen Sondheim’s mythical, murderous barber Sweeney Todd pronounced, in a somewhat different context: The work waits!

They had to move quickly before military police, tasked with securing the airport, saw what was happening. The rebels targeted 13 private jets parked or preparing for takeoff, at least two belonging to NetJets, the Berkshire Hathaway subsidiary that bills itself as the world’s largest jet company and sells fractional ownership shares in private business jets.

They had to move quickly before military police, tasked with securing the airport, saw what was happening. The rebels targeted 13 private jets parked or preparing for takeoff, at least two belonging to NetJets, the Berkshire Hathaway subsidiary that bills itself as the world’s largest jet company and sells fractional ownership shares in private business jets. The justification is unarguable. Large personal fortunes feed carbon consumption and make a mockery of programs to curb it. As well, the surplus wealth of the superrich is probably the lone source of capital that can finance the worldwide uptake of greener energy and also pay for adaptation where it’s most critical.

The justification is unarguable. Large personal fortunes feed carbon consumption and make a mockery of programs to curb it. As well, the surplus wealth of the superrich is probably the lone source of capital that can finance the worldwide uptake of greener energy and also pay for adaptation where it’s most critical. “What the Schiphol people needed to do is destroy the airplanes on the tarmac and then destroy the airplane manufacturers,” said an ecosaboteur named Stephen McRae, an acquaintance of one of the authors, who recently completed a six-year prison sentence for industrial sabotage. Although he no longer participates in such criminal acts of destruction, he has a point. The planes grounded on November 5 are already back in the air. That doesn’t diminish the value of what the Schiphol rebels did, however. Actions that disrupt carbon comfort without violence or hardship are morale-building, the material from which more actions and eventually mass movements are made.

“What the Schiphol people needed to do is destroy the airplanes on the tarmac and then destroy the airplane manufacturers,” said an ecosaboteur named Stephen McRae, an acquaintance of one of the authors, who recently completed a six-year prison sentence for industrial sabotage. Although he no longer participates in such criminal acts of destruction, he has a point. The planes grounded on November 5 are already back in the air. That doesn’t diminish the value of what the Schiphol rebels did, however. Actions that disrupt carbon comfort without violence or hardship are morale-building, the material from which more actions and eventually mass movements are made.

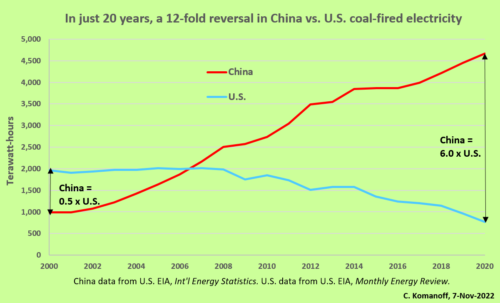

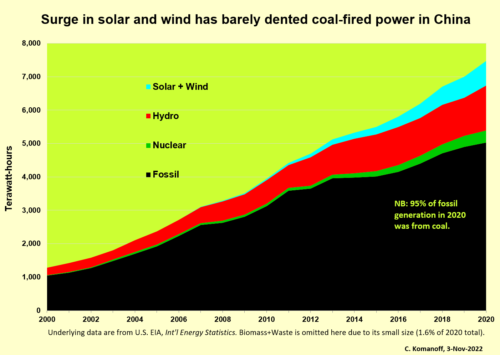

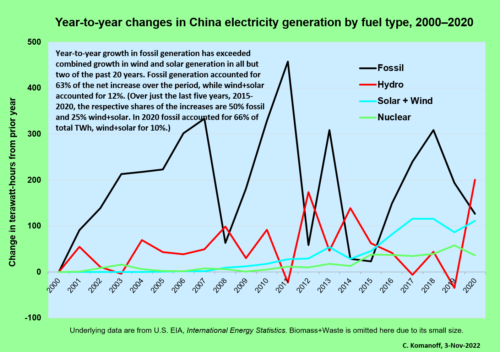

Those two years coincided with a flowering of climate optimism, with the U.S. and China reaching a bilateral agreement to curb emissions — ostensibly dissolving the “alliance of denial” by which both countries used each other’s inaction as a pretext to forego action on climate — and setting the stage for the 2015 Paris climate accord. Beginning in 2016, however, China’s fossil-fuel electricity generation (again, overwhelmingly coal-fired) recovered most of its prior increase pace. Year-to-year growth in fossil output has averaged 200 annual terawatt-hours since then.

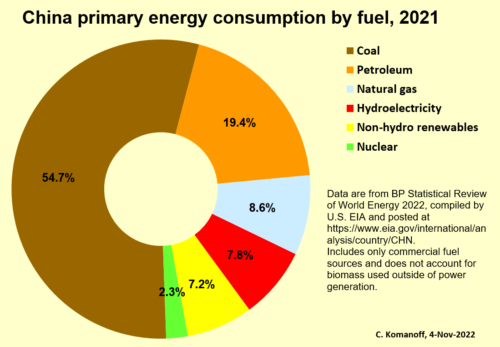

Those two years coincided with a flowering of climate optimism, with the U.S. and China reaching a bilateral agreement to curb emissions — ostensibly dissolving the “alliance of denial” by which both countries used each other’s inaction as a pretext to forego action on climate — and setting the stage for the 2015 Paris climate accord. Beginning in 2016, however, China’s fossil-fuel electricity generation (again, overwhelmingly coal-fired) recovered most of its prior increase pace. Year-to-year growth in fossil output has averaged 200 annual terawatt-hours since then. But in China, no single energy application rivals the burning of coal to produce electricity. It accounts for around one-third of the country’s primary energy consumption — a figure we computed by multiplying coal’s 55 percent share of 2021 China primary energy (see donut chart) and electricity’s estimated 60 percent share of the country’s total coal consumption (per the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s

But in China, no single energy application rivals the burning of coal to produce electricity. It accounts for around one-third of the country’s primary energy consumption — a figure we computed by multiplying coal’s 55 percent share of 2021 China primary energy (see donut chart) and electricity’s estimated 60 percent share of the country’s total coal consumption (per the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s

The Inflation Reduction Act likewise marks a turning point, at least for the time being, on long-running, world-damaging U.S. climate helplessness. True,

The Inflation Reduction Act likewise marks a turning point, at least for the time being, on long-running, world-damaging U.S. climate helplessness. True,

Even a fully intact Biden plan would have fallen short of its goals. Nevertheless, its scope and reach would have far surpassed any climate program by any major nation. Build Back Better’s carbon reductions and climate benefits would have been numerically substantial and would also have triggered parallel policies in other countries.

Even a fully intact Biden plan would have fallen short of its goals. Nevertheless, its scope and reach would have far surpassed any climate program by any major nation. Build Back Better’s carbon reductions and climate benefits would have been numerically substantial and would also have triggered parallel policies in other countries. During the run-up to that vote we published

During the run-up to that vote we published  D. Like Andreas Malm, we believe that direct action in defense of climate and earth needs to come to the fore, as we proposed in two posts last summer inspired by Malm’s book: Christopher Ketcham’s essay,

D. Like Andreas Malm, we believe that direct action in defense of climate and earth needs to come to the fore, as we proposed in two posts last summer inspired by Malm’s book: Christopher Ketcham’s essay,

No federal legislation with a price on carbon has advanced to a floor vote since the “Waxman-Markey”

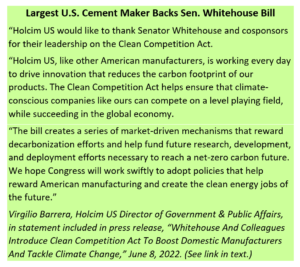

No federal legislation with a price on carbon has advanced to a floor vote since the “Waxman-Markey”  Whitehouse sees his bill as a way to use U.S. trade policy to drive climate action. He also views its potential to boost U.S. industrial competitiveness as a way to attract bipartisan support. Holcim U.S., whose parent company, Lafarge Holcim, is America’s largest cement manufacturer,

Whitehouse sees his bill as a way to use U.S. trade policy to drive climate action. He also views its potential to boost U.S. industrial competitiveness as a way to attract bipartisan support. Holcim U.S., whose parent company, Lafarge Holcim, is America’s largest cement manufacturer,

Promising developments like

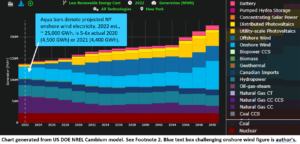

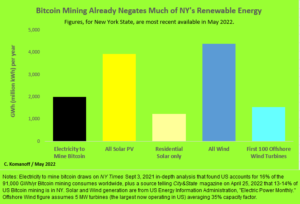

Promising developments like  While New Yorkers are accustomed to thinking of our state as resource-poor, crypto miners are now exploiting half-a-dozen hydro power sites and formerly boarded-up fossil-fuel plants in northern and western New York. One industry source

While New Yorkers are accustomed to thinking of our state as resource-poor, crypto miners are now exploiting half-a-dozen hydro power sites and formerly boarded-up fossil-fuel plants in northern and western New York. One industry source  This isn’t to hold out carbon taxing as a one-bullet crypto killer — we need many bullets for that, the bigger the better — but to illustrate its broad potential to stop frivolous (and in this case imbecilic) new uses of electricity before they can gain a foothold.

This isn’t to hold out carbon taxing as a one-bullet crypto killer — we need many bullets for that, the bigger the better — but to illustrate its broad potential to stop frivolous (and in this case imbecilic) new uses of electricity before they can gain a foothold.

Amen. The failures propping up US carbon emissions are multiple. Not just Senator Joe Manchin, who torpedoed President Biden’s Build Back Better clean-energy legislation. Not just the Senate Republicans, any one of whom could have cast the critical 50th vote. And not just Big Carbon, whose

Amen. The failures propping up US carbon emissions are multiple. Not just Senator Joe Manchin, who torpedoed President Biden’s Build Back Better clean-energy legislation. Not just the Senate Republicans, any one of whom could have cast the critical 50th vote. And not just Big Carbon, whose