If you believe that the best policy for cutting U.S. carbon emissions — and the easiest political sell — is “cap-and-dividend,” you’re loving a NY Times op-ed keyed to a bill being introduced today by Rep. Chris Van Hollen (D-MD).

Van Hollen’s Healthy Climate and Family Security Act of 2014 would (i) create a permit system covering CO2 emissions for all fossil fuels extracted or brought into the U.S., (ii) auction off permits equaling U.S. emissions in 2005, (iii) ratchet down the number of permits by 80% by 2050, and (iv) distribute all of the proceeds “to the American people as equal dividends for every woman, man and child,” according to the op-ed, entitled The Carbon Dividend.

CTC finds that a 100% carbon-dividend will improve finances for 65% of U.S. households, not for 80%.

A bill structured like that is fairly ambitious, and it’s good to see it submitted to Congress alongside the McDermott Managed Carbon Price Act of 2014 introduced two months ago on May 28. (Our write-up of the McDermott bill is here.) And the Times op-ed, by U-Mass economics professor James Boyce, is written with unusual grace and persuasiveness, especially at the start:

From the scorched earth of climate debates a bold idea is rising — one that just might succeed in breaking the nation’s current political impasse on reducing carbon emissions. That’s because it would bring tangible gains for American families here and now.

A major obstacle to climate policy in the United States has been the perception that the government is telling us how to live today in the name of those who will live tomorrow. Present-day pain for future gain is never an easy sell. And many Americans have a deep aversion to anything that smells like bigger government.

What if we could find a way to put more money in the pockets of families and less carbon in the atmosphere without expanding government? If the combination sounds too good to be true, read on.

That’s terrific writing, and smartly keyed to the compelling theme that climate policy need not be sacrificial or a greased path to so-called big government.

But the op-ed raises a handful of cautionary flags worth attending to:

First, why debut the cap with enough permits to cover 2005-level emissions? U.S. CO2 emissions are now (2013) 9 percent less than in 2005. (See CTC’s carbon-tax spreadsheet model [Excel download], Summary tab, Cell Q121.) Auctioning 10 percent more permits than would have been needed last year would virtually guarantee anemic permit prices that won’t spark carbon-reducing investment and won’t deliver the kinds of dividends the public will be counting on. (Addendum: The bill is now available (pdf) on Rep. Van Hollen’s Web site, and on p. 6 specifies that year-2016 permits will be 10% less than 2005 emissions, largely vitiating this concern.)

Second, the op-ed is silent as to how the Van Hollen bill will handle permit trading. This question goes to the paradox at the heart of cap-based systems: without trading, the market signals will be cordoned into a thousand separate sectors, without the fluidity needed to engender the lowest-cost array of carbon-reducing investments and behaviors; but trading invites the magicians of high finance to game the system with complex derivatives that will destabilize and hide the price of permits, impeding the intended long-term investments in renewables and efficiency.

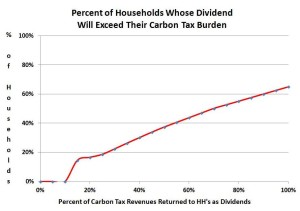

Third — and this is an issue with the op-ed rather than the bill per se — Prof. Boyce’s promise that “more than 80 percent of American households would come out ahead financially” may not withstand close scrutiny. As skewed as U.S. wealth, spending and energy consumption are toward the upper echelons, it’s unlikely that so much fossil fuel use is purchased by the top quintile that the dividend checks going to everyone in the bottom four quintiles will exceed their passed-through higher carbon costs. (My best estimate, shown graphically here, is that around 65% of households will come out ahead financially under a 100%-dividend system with either a carbon cap or tax.)

Fourth, the op-ed took this gratuitous swipe at a carbon tax:

Unlike a carbon tax, which brings in more revenue for the government, Mr. Van Hollen’s bill is, in effect, a tax cut.

Ouch. That one sentence undercuts work by carbon-tax advocates to educate policymakers and the public that a carbon tax, like a cap, can be revenue-neutral via either “tax swaps” that phase out existing federal taxes like payroll taxes as the carbon tax revenue is phased in, or the same dividend approach embodied in the Van Hollen bill. Any tax, including one on carbon pollution, need not be a revenue-raiser for bigger government (or even for deficit reduction). Indeed, the choice of pricing mechanism (permits or fees) and the choice of revenue treatment (dividend, tax swap, or revenue-raiser) are independent of each other.

To spell it out: A tax or fee can have (or not have) a dividend as easily as can a cap. And the magnitude of the dividend will be a good deal more predictable and steady under a fee-and-dividend system than with cap-and-dividend, thus guaranteeing a stronger version of the compact with American households that Boyce rightly touts (“The tighter the cap, the bigger the dividend. Voters not only would want to keep the policy in place for the duration of the clean energy transition, they would want to strengthen it.”)

Finally, there’s a larger question as to the political salience of cap-based federal climate legislation. The Van Hollen bill seems curiously stuck in 2009-2010, when the Big Green groups were pushing furiously for cap-and-trade in the form of the Waxman-Markey bill. With the lords of Wall Street no longer valorized, and with the opacity of cap-based systems now seen as a drawback instead of an asset, many carbon-pricing advocates have moved on. Sentiment is coalescing around a carbon tax, especially the fee-and-dividend approach supported by the fast-growing Citizens Climate Lobby and embodied in the McDermott bill noted earlier.

Sage says

It’s just stupid to have a cap. Good simple carbon tax is what we need. Let’s not mince words. Let’s not make this more complicated than it must be. The simple carbon tax works best. It needs to be revenue-neutral, and the revenue needs to either be distributed as a flat dividend, or else as a cut to the payroll and self-employment taxes or some other seriously progressive tax cuts. Cutting the taxes on work will stimulate job creation, or rather reduce the existing drag that the government imposes on job creation. We need that badly, and we need to lower emissions. It’s a win/win except for the fossil fuel companies, who deserve to lose because they’ve been profiting at our expense for far too long.

Kara Kockelman says

This conversation (especially the part about how some income groups may benefit) reminds me of our very separate work & findings, when playing with Americans’ expenditure (CEX) data, and trying to anticipate the effects of a cap (at the household level, per household member) versus carbon taxes. Related to this, I have long worried that taxes embedded in prices are too nuanced for most Americans to respond to, though I realize that per-head caps are trickier to administer. (Note: We have to have fuel economy standards because car buyers are too myopic to value gas savings appropriately, for example.) Rebates (as captured in our paper) creates rebound effects (with more money to spend, on energy-consuming activities), but there are few good ways around that. Please see http://www.ce.utexas.edu/prof/kockelman/public_html/TRB10Cap&Tax.pdf for more information. It is a very imperfect study, but the best we could do, given the complexity of the issue, and nature of the data sets available (and our own cognitive limitations, of course!). It relates tightly to these discussions, and I hope top investigators can move this kind of work forward for the world.

Chris says

Sage makes exactly the argument I would for a revenue-neutral fee or tax. I oppose any cap-and-dividend scheme unless there is a compelling argument for the political advantage of a cap over a fee. Frankly, I suspect the only credible argument for a cap is that it would make environmental purists happier because they fundamentally distrust economic arguments and want a hard cap. However, environmental purists are likely to go along with a fee if it ever got started — they only need to hear Charles point about the cap being set higher than needed to force conservation to see that any fee is a net win whereas some caps are useless or can become useless as the underlying economics change — witness the collapse of the carbon price is Europe.

Dan Galpern says

Beyond the potential for trading mischief, I am also concerned with the lack of a floor-price. One could even design a cap and dividend with a rising floor so as to gain at least a measure of price certainty. The risk of tinkering and opaque trading would, perforce, still not be eliminated.

JK says

Maybe a whole generation of thinkers has been so immersed in environmental regulations that they cannot think straight anymore. Charlie is generous to give this one clap. It’s dumb. It’s much less efficient and flexible than a carbon tax and will cost far more to administrer. Less government? How many regulators and lawyers will it take to ensure that the auction of these credits will work properly? Is this all about avoiding the word “tax.” Can we come up with a better word then instead of being stuck with far inferior way of reducing carbon emissions? How about we sell carbon revenue anticipation bonds and bribe the public into supporting the Carbon Neutral Plan.

Alan Lubow says

Jenkins says it elegantly. On the other hand, cap and trade will create “an infinite and unpredictable variety of innovations ” by which the financial wizards will satisfy their profit and greed needs irrespective of carbon release into the atmosphere. Keep it simple and clean…

RJH says

To the average voter, a “cap” is just as good as a ‘tax’ — or even better, because automatically the word ‘cap’ frames the solution as “being someone else’s worry and expense” and not mine (not true of course). There are multiple reasons why a cap is inferior to a fee and rebate, but one is enforcement & associated costs. A cap needs CO2 measurement & compliance – all difficult. A fee on the other hand only requires collection – which is something governments already do well. British Columbia has already proven that a revenue-neutral carbon tax is both possible and economically beneficial.

Harley Wright says

Here is a comparison I used for Australia, comparing cap and trade (emissions trading scheme, viz ETS) with a carbon tax. Note, this mentions a ‘Direct Action’ plan. This is a dodgy proposal with negligible credibility. Don’t waste your time trying to work it out.

The table has not copied well. I can send you this in an email if you would like.

For a good review of potential measures you could look at the “Garnaut Climate Change Review[s]” of 2008 and 2011. Garnaut is an eminent economist and provides an excellent report on the options.

Note too, his support for Contraction and Convergence which is a fair means to deal with the issue internationally. Yes, it will cost money for high carbon countries like USA, Canada and Australia – but it provides fair payment to low-carbon countries. This payment [for their excess carbon entitlements] avoids the arbitrary provision of funds being argued under the COP/UNFCCC to support developing countries.

The table below suggests seven specific objectives as an adjunct to our current legal objects.

There are numbered comments below the table for each specific objective. In the Table I assess and score how three different carbon abatement measures achieve these objectives. The three measures are

a. an ETS

b. a carbon tax and

c. abatement subsidies

Scores range from 1 to 5 – see comments below table.

Score

Key objectives for carbon abatement policy ETS C tax Abatement Subsidies

1. Restrain emissions to a national cap 4 3 1

2. Able to change Carbon cap/target 5 4 1

3. Provide future Carbon costs 5 5 ?

4. Keep costs low – Australia

– International 5

5 4

5 2

2

5. Able to link with international carbon markets 5 1? 1

6. Meets polluter pays/ user pays principle 5 5 1

7. Supports developing countries 5 2 1

Scores: 1 Inadequate 2 Weak 3 Fair 4 Good 5 Excellent

Comments on ‘key objectives’ [by number]

1 Most emissions (~80%) can be efficiently ‘covered’ by an ETS or C tax. Complementary measures are needed for those emissions not covered by an ETS/C tax and are commonly less reliable.

2 Direct Action targets a 5% reduction (only) by 2020, which is inadequate and which many experts say is unlikely to be met by DA/ERF because of limited funding.

3 Future Australian carbon prices might be indicated roughly from the publication of contract details for approved projects under the ERF. But these have a maximum lifetime of five years. The carbon prices indicated will be of low reliability or value. The five-year limit on providing payments for imputed reductions is too low. It does not assist with investment planning for new assets with long lifetimes. The ERF lacks a carbon market. Conversely, an ETS or carbon tax enables emitters to buy forward-dated emissions permits as insurance to cover possible future price changes for their emissions. This is a strong benefit to prudent investment as the future abatement targets may vary. Industry (and the public generally) will be seriously disadvantaged without consistent future carbon pricing signals, which are needed for sound investment and process changes.

4 The ERF is wholly based on ‘additionality’, which is a poor method because it involves an imputed emissions baseline, is costly to manage and results in contestability and poor credibility. Anyone familiar with measurements based on additionality will know that there are many unavoidable assumptions and the resultant values have low credibility. This was covered earlier (page 9). Additionality, as a core element in the ERF, is one of its greatest flaws. With an ETS or carbon tax, this unreliable, cumbersome and second-best measure is unnecessary. An ETS or carbon tax requires a measure of direct emissions, most of which are readily measured, reported and verified under the existing National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Scheme (NGERS).

5 Linking with international markets allows Australia to access carbon emission units that could be less costly. This enables least-cost abatement on a global scale, and in Australia. As with any overseas trade, it affects our balance of payments.

6 The DA/ERF subsidises approved carbon abatement projects paid for with everyone’s taxes12. Consumers do not see the costs of embedded emissions. This is bizarre, particularly from a party that normally eschews subsidies. The operating Clean Energy Act is a sound carbon abatement system incorporating the ‘polluter pays’ and ‘user pays’ principles – which internalise environmental externalities to avoid market distortions. These principles are enthusiastically endorsed and embraced in modern economies. It is extraordinary that the Coalition Government would replace this simple, functioning and well principled scheme with a public subsidy to polluters that removes carbon prices in final consumption that would otherwise have the effect of encouraging price-rational carbon abatement.

7 With a carbon tax, there is no natural linkage to assist developing countries but this could be done separately using some of the government revenue from the carbon tax.

Direct Action with the ERF is clearly inferior to either the ETS or carbon tax in this appraisal.

Thomas Sterner says

Nice article Charlie. In my opinion both taxes and cap and trade can work well. Each has its specific advantages and disadvantages that are truly quite complex. The main problem is that years and even decades are going by without the US having either. The best policy therefore becomes the one that could get through Congress. I think Van Hollens Cap and Dividend would be great if it did pass. The mystery for me is why countries – in this case the USA – does these policies unilaterally. The big win would come if, in international negotiations each country agreed to do something like this (either through a tax or a cap).

Harold Erdman says

I agree with CTC that a carbon tax – or carbon dividend – is much better than any cap and trade mechanism, no matter what is done with the money. I also believe that cap-and-dividend is better than nothing, and if that’s the only thing Congress can pass, so be it.

However, I am extremely upset about Prof. Boyce saying “unlike a carbon tax, which brings in more revenue for the government, Mr. Van Hollen’s bill is, in effect, a tax cut.” This is not just gratuitous, it is completely false. No matter the mechanism for putting the price on carbon (either cap-and-trade or tax), all the money can be returned to the public and called a tax cut. I don’t mind honest intellectual differences as to which pricing mechanism is better. However, to use untruths to support one’s pricing mechanism over another does not help anyone. I’m sorry to say it just adds fuel to the scorched earth debate that Prof. Boyce decries.

James Boyce says

Thanks, Charles, for the kind word and thoughtful observations. I want to respond and also try to clear up a few points in other comments on your post.

You are, of course, right that it’s possible to have a revenue-neutral carbon tax. A tax (aka fee)-and-dividend is the first cousin to cap-and-dividend, and this could be a very good policy, too. I should have said “unlike a carbon tax that brings in more revenue” so as not to exclude the possibility for a carbon tax that doesn’t do so by virtue of dividends and/or tax shifts.

I prefer a cap (with 100% auction, hence no giveaways, no trading and no role for market manipulation), on the grounds that fixing the quantity of permits and letting their price vary is preferable to fixing the price and letting their quantity vary. But the last thing I want to do is perpetuate, let alone exacerbate, discord between cap-and-dividend and fee-and-dividend proponents – folks who I firmly believe should be allies.

I also agree with your preference, in the case of cap-and-dividend, for inclusion of a floor price for permits. In fact, the combination of a cap and a floor price would neatly synthesize a carbon cap and a carbon tax, with the floor price being the tax and the cap (and associated auctions) coming into play if/when the tax fails to bring emissions within the targeted ceiling. Carbon cap proponents often worry that a tax would be set too low to secure adequate reductions in the quantity of emissions; carbon tax proponents often worry that a cap would be set too loosely to secure adequate increases in the prices of fossil fuels. Combining a quantity cap with a price floor would address both these concerns. As legislative interest in climate policy revives, perhaps there will be scope for some combination of the ideas advanced in the McDermott and Van Hollen bills.

What is most important, in my view, is a shared commitment to dividends as the major (if not exclusive) use of revenue from carbon pricing. Dividends translate into practical policy the ethical principle voiced in the opening clauses of Rep. Van Hollen’s bill: “The atmosphere is a common resource that belongs equally to all.” I believe that most Americans – and even, if pressed, most American politicians – would agree that the air belongs “equally to all.” The revenue from payments for use this scarce resource should go directly to the people, not to the government, not to fossil fuel corporations.

Moreover, dividends will protect the majority of American households, including the middle class, from the adverse effects of carbon prices of their net incomes. With 100% of the revenue returned to the people (as proposed by Reps. McDermott and Van Hollen), a substantial majority will come out ahead in sheer pocketbook terms, even without counting environmental benefits. Dividends, I believe, are the only way to secure durable public support in the face of rising fossil fuel prices that necessarily will come with carbon pricing. We need a policy that will last through the decades of the clean energy transition, regardless of which party controls the legislature or the White House. Much as universal coverage has sustained Social Security and Medicare over the years, universal dividends can sustain effective climate policy.

Some additional points:

With 100% auctions there is no need for permit trading. A more complete name for cap-and-trade is cap-and-giveaway-and-trade. In the Van Hollen bill, as in a carbon tax, there are no permit giveaways. Only fossil fuel firms can buy permits. The “magicians of high finance” are out of the picture.

The reason that more than 80% of households rather than around 65% would benefit financially is that the household sector accounts for only about 2/3 of U.S. carbon consumption. Most of the rest of comes from government. The money that government pays as a result of carbon pricing will go to the people, too. And the Van Hollen bill would make the carbon dividends tax-free.

Why return the money via dividends rather than via tax cuts? Instead of embodying the principle that the atmosphere belongs equally to all, a tax cut would return carbon revenues to the people in proportion to their taxes. This payback would come hidden in the workings of the tax system, rather than in the highly visible (and therefore politically more potent) form of dividends. Moreover, cuts in payroll taxes would not lead to more jobs in an economy beset by chronic unemployment (aka excess labor supply) and idle capital. Supply-side economics assumes that we live in a world in which resources are fully employed, but here in the real world millions of people can’t find jobs, while commercial banks and large nonfinancial corporations sit on massive hoards of excess cash and liquid assets (for numbers, see my colleague Robert Pollin’s excellent book, Back to Full Employment).

Enforcement and administration costs would differ little between a carbon tax and a carbon cap with 100% of permits auctioned. In both cases it will be necessary to enforce the law: a permit must be surrendered for each ton of fossil carbon that enters the economy. In this respect, it doesn’t matter whether the permits are sold at a constant price (set by a tax) or sold at a price that can vary from auction to auction (with the quantity set by a cap). The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative in the northeastern states has been auctioning carbon permits successfully since 2008. It’s not rocket science, and administering a permit auction is not expensive.

Finally, Thomas Sterner is certainly right that unilateral policies adopted by single countries will not suffice to address the global problem of climate change. But a cap (or fee)-and-dividend policy makes good economic and political sense even while we await an international accord: it would bring economic benefits to the majority of households; it would bring cleaner air by curbing emissions of particulates, carbon monoxide and other co-pollutants released by burning fossil fuels; and it would position the country to be a leader in development of the energy efficiency and clean energy technologies of the future.

Peter Barnes says

What many people on this site are missing is that a cap on carbon suppliers, with 100% auctions, no offsets and permit trading among actual fuel suppliers only, is NOT THE SAME as cap-and-trade as embodied in the Waxman-Markey bill and the EU carbon trading system.

An EMISSIONS cap-and-trade system, we all agree, is far too complicated, leaky and costly to enforce. And offsets are a massive evasion sinkhole. But a carbon supply cap is completely different, much simpler and tighter, and it can’t leak. If carbon doesn’t come into the economy, it can’t go out. End of story.

It’s time to stop beating the dead horse of cap-and-trade. The Van Hollen bill is not that. It will actually squeeze carbon out of our economy, with a timetable, physical limits AND a carbon price. That beats a carbon price alone.

I like the idea of auctioning diminishing supply permits with a price floor (but not a ceiling). Could we all agree on that?