The real fossil fuel subsidy is the absence of carbon pricing.

Over the past decade, much climate discourse has latched onto the idea that the global fossil fuel industry is being propped up by “massive fossil fuels subsidies.” The corollary, widely voiced by climate activists and in sympathetic media, is that terminating those subsidies is the climate’s low-hanging fruit. Take away fossil fuel subsidies, the argument goes, and extraction and use of coal, oil and gas will collapse under the weight of high prices and be supplanted by renewable energy.

This belief, though grossly overstated, has legitimate roots in the long and painful experience of fossil fuels’ environmental and social destructiveness. Not just climate chaos is massively “underpriced,” so are “local” air pollution, which kills millions around the world each year; road traffic crash deaths enabled by petrol-fueled cars and trucks (more megadeaths); and fossil fuel extraction that damages Indigenous lands, often irreversibly — a phenomenon documented decades ago by environmental advocates. (See, for example, CTC director Charles Komanoff’s seminal 1994 journal article for the Pace Law School Environmental Review.

The costs of fossil fuel extraction and usage are indeed huge. For the most part, however, those costs aren’t taxpayer-funded giveaways to fossil-fuel producers; they’re “externalities,” or, more properly, “negative externalities” — unpriced damages.

Global fossil fuel subsidies are nowhere near $7 trillion a year. They’re $1.3 trillion. (Read the fine print.)

This confusion effectively went viral in 2015, when the International Monetary Fund began classifying as “subsidies” not just giveaways from taxpayers to fossil fuel producers but also pollution damages from burning those fuels, which are several times as large.

Actually, the IMF’s periodic reports on subsidies, which are meticulous and invaluable, make the distinction fairly clear — but only in the fine print. The reports’ topline statements about “governments’ … $7 trillion subsidies” invite confusion or misrepresentation. Unfortunately, some of the world’s most respected media, including The Guardian newspaper, the New Yorker magazine, and the New York Times, have repeatedly amplified the “massive subsidies” line.

Screenshot from August 2023 IMF post (link: https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2023/08/24/fossil-fuel-subsidies-surged-to-record-7-trillion). Only hyper-meticulous readers would see that “explicit subsidies” are less than 20% of the $7 billion total.

During the Sept. 2023 U.N. General Assembly meeting, for example, the Times‘ report on the secretary general’s climate address included a subhead, “António Guterres told world leaders gathered in New York that their efforts to address the climate crisis had come up ‘abysmally short.’” Here’s the lede:

The world’s top diplomat, António Guterres, the United Nations secretary general, on Tuesday told world leaders their efforts to address the climate crisis had come up “abysmally short” and called on them to do what even climate-ambitious countries have been reluctant to do: stop expanding coal, oil and gas production. “Every continent, every region and every country is feeling the heat, but I’m not sure all leaders are feeling that heat,” he said in his opening remarks to presidents and prime ministers assembled for their annual gathering in the General Assembly. “The fossil fuel age has failed.”

U.N. Chief’s Test: Shaming Without Naming the World’s Climate Delinquents, Sept. 19, 2023

Powerful statement, forceful coverage. Several paragraphs later, however, came this:

Despite [the secretary general’s] exhortations, governments have only increased their fossil fuel subsidies, to a record $7 trillion in 2022. Few nations have concrete plans to move their economies away from fossil fuels, and many depend directly or indirectly on revenues from coal, oil and gas. The human toll of climate change continues to mount. (emphasis added)

From The Guardian, Oct 6, 2021, which calculated $11 million a minute by dividing the International Monetary Fund’s then-current $5.9 trillion annual “subsidies” figure by the number of minutes in a year. Direct taxpayer supports were then just $600 billion of the total. The remaining $5.3 trillion were externality costs.

The link to the story’s $7 trillion figure is to the IMF Aug. 24, 2023 blog, Fossil Fuel Subsidies Surged to Record $7 Trillion, excerpted above. We reprinted the blog’s opening section to make clear the Fund’s blunder in passing off externality costs as subsidies. Only by pushing past the large-font headline and four fine-print paragraphs will readers see a subtle bar graph simplistically titled “Fossil fuel subsidies topped $7 trillion last year.”

The IMF graph’s legend tries to be helpful, distinguishing between “explicit” (dark red, bottom) and “implicit” (light red, top) “subsidies.” Or you can squint down to the caption to find out that “Explicit subsidies [are] undercharging for supply costs [while] Implicit subsidies [are] undercharging for environmental costs and forgone consumption taxes, after accounting for preexisting fuel taxes and carbon pricing.”

Clear now? Alas, it’s easier to gloss over the distinction and, as did the Times, report the whole business as $7 trillion in fossil fuel subsidies.

Similar framing led the Guardian‘s redoubtable environmental editor Damian Carrington down the same primrose path two years earlier, as shown in the screenshot at right above, from an October 2021 story.

The Guardian headline misleadingly cast fossil fuel damages as giveaways to industry. While that’s true in a sense, conflating the two props up the simplistic — and untrue — notion that all that’s needed to undo dependence on fossil fuels is to eliminate government subsidies.

U.S. fossil-fuel subsidies are even smaller, in relative terms

Direct U.S. governmental support of fossil fuel exploration and production was estimated in 2014 by the resolutely anti-Big Oil research group Oil Change International to be only around $22 billion a year.

In 2014 Oil Change Int’l estimated U.S. FF subsidies to be just $22 billion a year.

That figure, while not quite chicken feed, still equates to just a few percent of “end user” expenditures on fossil fuels, which currently (2023) run at around $1 trillion pear year. Accordingly, taking away the $22 billion largesse, though a financial blow to the fossil fuel industry, would trigger only a mild rise in fossil fuel prices — not nearly enough to fundamentally alter the market equations that still favor fossil fuels over renewables in much of the energy sector.

Unfortunately, OCI’s meticulous analysis must have escaped the notice of the New Yorker magazine some years later, which printed this offhand but distorting remark in an Oct. 2021 article about prospects for fusion power:

This year, the U.S. government will spend some six hundred and seventy million dollars on nuclear fusion. That’s a lot of money, but six hundred and fifty billion—the amount the I.M.F. estimates that U.S. taxpayers spent on fossil-fuel subsidies last year—is quite a bit more. (emphasis added)

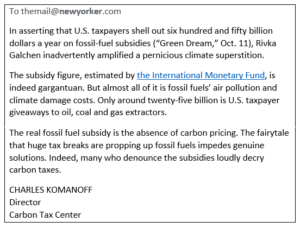

Our letter attempted to correct the New Yorker’s misstatement of U.S. fossil fuel subsidies.

Wrong, as we pointed out in a letter to the editor that didn’t make it into print, shown at right.

Alas, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders has also drunk the subsidies kool-aid. In a speech on the Senate floor in December 2020, Vermont’s Bernie Sanders decried the “hundreds of billions of dollars” in corporate welfare given to fossil fuel companies. (The clip, from Democracy Now! on Dec. 21, starts at around 19:25.)

Bernie Sanders said “corporate welfare” but he probably meant subsidies. The real fossil fuel subsidy is the absence of carbon pricing.

A related construct is that the U.S. and other countries massively subsidize the extraction and supply chain for fossil fuels. These subsidies are sometimes said to be why coal, oil and gas still dominate energy supply at the expense of efficiency, wind and solar. According to this view, eliminating these subsidies — which ought to be easier politically than enacting a robust carbon tax — should take center stage in efforts to reform energy pricing and markets.

Unfortunately, branding dirty energy’s pollution damages as a subsidy quickly spread. This, from a New York Times review of new climate-crisis books in April, 2019, was typical:

One prospective technique to scrub carbon from the atmosphere would cost $3 trillion a year, a colossal amount — but significantly less than the current level of subsidies paid out globally for fossil fuel, estimated at $5 trillion.

No, pre-tax subsidies “paid out globally for fossil fuel” at the beginning of the prior decade were only around $330 billion a year, or one-fifteenth of the $5 trillion total, according to the IMF (see p. 17 of the fund’s 2015 Working Paper). The rest was externality costs: climate harms, pollution harms, and other damages from underpriced automobile use; the antidotes to which, of course, are carbon taxes, other pollution taxes and road pricing.

Subsidizing clean energy will cut carbon, but not as much as a robust carbon tax.

Many believe that devoting tax revenues to support, commercialize and bring down the price of clean energy will enable the U.S. and other societies to transition quickly from fossil fuels. “No carbon tax needed,” according to this scenario; wind, solar and energy efficiency will out-compete fossil fuels in energy markets once they’ve been granted appropriate price supports to overcome initial hurdles to commercialization.

This idea has strong elements of truth. But we regard as wishful thinking the idea that subsidizing down the cost of clean energy can do more to push out fossil fuels than raising those fuels’ market prices through carbon taxing.

In broad terms, our view is that human appetites for energy are so boundless that, absent robust prices on carbon emissions, energy demand will outstrip the potential of even optimized and advanced solar and wind power systems. More analytically, in comments submitted to the Senate Finance Committee in 2014, we demonstrated that even a perfectly designed U.S. energy subsidy program — one that dismantled fossil fuel subsidies while buying down the price of renewable power and fuels — couldn’t compare in effectiveness to a carbon tax.

We summarized and linked to those comments in this blog post: CTC Tells Senate Finance Committee: Carbon Tax Beats Clean-Energy Subsidies, Hands Down. (Full report, 22 pages here (pdf).)

A kindred spirit (on subsidies): Matthew Yglesias

In June 2024, the highly visible and iconoclastic blogger Matthew Yglesias posted a broadside, The case of the mystery fossil fuel subsidy, as part of a longer piece, Elite misinformation is an underrated problem. Yglesias’s take mirrors ours: The IMF is subverting its meticulous and valuable analysis with “misleading headlines, which are then picked up and bounced around by mainstream media outlets.”

Yglesias begins by recalling that “Years ago [he saw] lots of stories with headlines like this:”

- “Fossil Fuel Firms Are Subsidized at a Rate of $11 Million Per Minute” — Mother Jones

- “Why Are Taxpayers Propping Up the Fossil Fuel Industry?” — NYT

- “Why Are Governments Still Subsidizing Fossil Fuels?” — Washington Post

- “Explainer: Global fossil fuel subsidies on the rise despite calls for phase-out” — Reuters

(Note that all of Yglesias’s examples are quite recent; the last three are from 2023, and the first, the Mother Jones piece, is from 2021.)

His takeaway at the time was that governments and policymakers could circumvent the political problems of taxing carbon emissions by “just get[ting] global governments to cut their massive subsidies for fossil fuel use first.”

Only later, when Yglesias, like us, looked under the hood of the IMF analyses and saw the fine print, did he deduce that “The vast majority of the ‘subsidies’ are ‘implicit subsidies,’ which include ‘undercharging for environmental costs.’ In other words, they [IMF] are characterizing governments’ failure to impose a carbon tax as a ‘subsidy’ for fossil fuel use.”

“They [IMF] are not lying, exactly,” Yglesias notes. “But it’s hard to understand why the IMF would do this” — undermine their work in misleading headlines — “unless they thought it was a good idea to trick people.”

Interestingly, Yglesias’s post has its own subtle misstep on carbon pricing:

If world governments came together to get each state to locally impose a carbon tax equal to the global social cost of carbon, that would raise approximately $7 trillion in revenue. And that revenue could be used to reduce outstanding public sector debt burdens or reduce broad taxes on consumption and labor. In the aggregate, the world would end up with cleaner air and a more stable climate, and the economic cost of doing this would be minimal, or arguably even negative.

Actually, the primary value of global or even robust national carbon taxes is not to be found in their vast revenue potential, but in the fact that the resulting higher prices for fossil fuels will stimulate shifts to lower-carbon fuels (wind, solar, nuclear) and reductions in energy consumption, period. It seems that even a policy-savvy pundit like Yglesias doesn’t fully appreciate the power of pricing to not just change but transform behavior, investment and culture.