This page is taken, with light edits, from Climate Change: Global Temperature, a NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) web page dated March 15, 2021, composed by NOAA staffers Rebecca Lindsey and LuAnn Dahlman. It is notable for its fine scholarship and may be useful for pushing back against denials that Earth’s temperatures have been rising relentlessly and at an accelerated pace. We’ve posted it in Politics, on account of the politicized nature of climate change discourse.

Given the size and tremendous heat capacity of the global oceans, it takes a massive amount of heat energy to raise Earth’s average yearly surface temperature even a small amount. The 2-degree increase in global average surface temperature that has occurred since the pre-industrial era (1880-1900) might seem small, but it means a significant increase in accumulated heat. That extra heat is driving regional and seasonal temperature extremes, reducing snow cover and sea ice, intensifying heavy rainfall, and changing habitat ranges for plants and animals—expanding some and shrinking others.

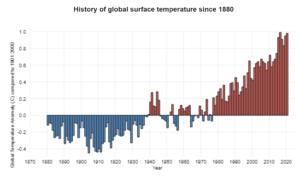

Graph shows avg annual global temps since 1880 compared to long-term avg (1901-2000). Zero line represents long-term avg temp for the whole planet; blue and red bars show differences above or below avg for each year. For interactive version, go to NOAA source doc.

Conditions in 2020

According to the 2020 Global Climate Report from NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, every month of 2020 except December was in the top four warmest on record for that month. (In December, the presence of a moderately strong La Niña event cooled the tropical Pacific Ocean and dampened the global average warmth. The month turned out as “only” the eighth warmest December on record.)

Despite La Niña, 2020 ranked as the second-warmest year in the 141-year record for the combined land and ocean surface, and land areas were hottest on record. Many parts of Europe and Asia were record warm, including most of France and northern Portugal and Spain, most of the Scandinavian Peninsula, Russia, and southeastern China. An even larger portion of the globe was much warmer than average, including most of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. The heat reached all the way to the Antarctic, where the station at Esperanza Base, at the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, appeared to set a new all-time record high temperature of 65.1 degrees Fahrenheit (18.4 degrees Celsius) on February 6, 2020.

Change over time

Though warming has not been uniform across the planet, the upward trend in the globally averaged temperature shows that more areas are warming than cooling. According to NOAA’s 2020 Annual Climate Report the combined land and ocean temperature has increased at an average rate of 0.13 degrees Fahrenheit ( 0.08 degrees Celsius) per decade since 1880; however, the average rate of increase since 1981 (0.18°C / 0.32°F) has been more than twice that rate.

The 10 warmest years on record have all occurred since 2005, and 7 of the 10 have occurred just since 2014. Looking back to 1988, a pattern emerges: except for 2011, as each new year is added to the historical record, it becomes one of the top 10 warmest on record at that time, but it is ultimately replaced as the “top ten” window shifts forward in time.

Models project that by 2020, global surface temperature will be more than 0.5°C (0.9°F) warmer than the 1986-2005 average, regardless of which carbon dioxide emissions pathway the world follows. This similarity in temperatures regardless of total emissions is a short-term phenomenon: it reflects the tremendous inertia of Earth’s vast oceans. The high heat capacity of water means that ocean temperature doesn’t react instantly to the increased heat being trapped by greenhouse gases. By 2030, however, the heating imbalance caused by greenhouse gases begins to overcome the oceans’ thermal inertia, and projected temperature pathways begin to diverge, with unchecked carbon dioxide emissions likely leading to several additional degrees of warming by the end of the century.

About surface temperature

The concept of an average temperature for the entire globe may seem odd. After all, at this very moment, the highest and lowest temperatures on Earth are likely more than 100°F (55°C) apart. Temperatures vary from night to day and between seasonal extremes in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. This means that some parts of Earth are quite cold while other parts are downright hot. To speak of the “average” temperature, then, may seem like nonsense. However, the concept of a global average temperature is convenient for detecting and tracking changes in Earth’s energy budget—how much sunlight Earth absorbs minus how much it radiates to space as heat—over time.

To calculate a global average temperature, scientists begin with temperature measurements taken at locations around the globe. Because their goal is to track changes in temperature, measurements are converted from absolute temperature readings to temperature anomalies—the difference between the observed temperature and the long-term average temperature for each location and date. Multiple independent research groups across the world perform their own analysis of the surface temperature data, and they all show a similar upward trend.

Temperature records from NOAA, NASA, and the University of East Anglia all show an increase from the start of the 20th-century through 2019. The year 2019 counted among the top three warmest years on record. Background image from NOAA DISCOVR/EPIC. Graph by NOAA Climate.gov based on data from the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society’s State of the Climate 2019.

Across inaccessible areas that have few measurements, scientists use surrounding temperatures and other information to estimate the missing values. Each value is then used to calculate a global temperature average. This process provides a consistent, reliable method for monitoring changes in Earth’s surface temperature over time. Read more about how the global surface temperature record is built in our Climate Data Primer.

References

Sánchez-Lugo, A., Berrisford, P., Morice, C., and Argüez, A. (2018). Temperature [in State of the Climate in 2018]. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 99(8), S11–S12.

NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, State of the Climate: Global Climate Report for Annual 2020, online January 2021, retrieved on March 15, 2021 from https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/sotc/global/202013.

IPCC, 2013: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group 1 to the 5th Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Stocker, T.F., D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex and P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.