This page reprints writings about the pandemic that touch on the climate crisis and the future of our species. These selections, by a Notre Dame educator, a Pulitzer-Price winning novelist, a leading editor and public intellectual, a journalist recalling Europe’s WWII descent into barbarism as he battles the coronavirus, an acclaimed author of “speculative fiction,” and an attorney specializing in energy projects, are evocative, wide-ranging and affirming. The set closes with a long but invigorating post on the eve of Pres. Biden’s inauguration by a leading climate journalist who declares, “The war on climate denial has been won. And that’s not the only good news.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I’ve Said Goodbye to ‘Normal.’ You Should, Too. by Roy Scranton

Don’t Give Up On America, by Marilynne Robinson

There are no good choices, by Ezra Klein

Fighting the Virus in Trump’s Plague: My body is a stranger. It is out there battling the enemy within.

By Roger Cohen

The Coronavirus Is Rewriting Our Imaginations, by Kim Stanley Robinson

From Climate to Covid, and Back Again, by Andrew Ratzkin

After Alarmism, by David Wallace-Wells

See also Can This Pandemic Spur Climate Action?, by Charles Komanoff & Christopher Ketcham, published on April 4 as a CTC blog post (and on the same day, in The Intercept). And check out Downturn in U.S. driving led 2020 global CO2 decline for an analysis of the countries and sectors that led the way in pushing 2020 world CO2 emissions substantially below 2019 levels.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I’ve Said Goodbye to ‘Normal.’ You Should, Too. by Roy Scranton (Jan. 25)

Climate change is upending the world as we know it, and coping with it demands widespread, radical action.

Scranton, director of the Notre Dame Environmental Humanities Initiative, is author of “We’re Doomed. Now What?” and “Learning to Die in the Anthropocene.”

The other night, I went to pick up takeout at a local Irish pub. It was a gray and rainy evening at the end of a long week, and my partner and I were suffering from Zoom fatigue. We love this pub not just because it has good food, but because it’s a living part of our community. Pre-Covid, they used to have Irish traditional music sessions, and any cold and snowy night you’d be greeted with a burst of cheer, a packed house, friends and families all out for a cozy good time.

Now it’s a ghostly quiet. Social distancing rules mean that even at max capacity, it still only has a tiny fraction of its usual clientele. Standing in that empty pub, haunted by the sense of what we were missing, I felt an ache for “normal” as acute as any homesickness I ever felt — even when I served in the Army in Iraq. I still feel the twinge every time I put on my mask. I want our normal lives back.

But what does normal even mean anymore?

It’s easy to forget that 2020 gave us not just the pandemic, but also the West Coast’s worst fire season, as well as the most active Atlantic hurricane season on record. And, while we were otherwise distracted, 2020 also offered up near-record lows in Arctic sea ice, possible evidence of significant methane release from Arctic permafrost and the Arctic Ocean, huge wildfires in both the Amazon and the Arctic, shattered heat records (2020 rivaled 2016 for the hottest year on record), bleached coral reefs, the collapse of the last fully intact ice shelf in the Canadian Arctic, and increasing odds that the global climate system has passed the point where feedback dynamics take over and the window of possibility for preventing catastrophe closes.

It’s easy to forget that 2020 gave us not just the pandemic, but also the West Coast’s worst fire season, as well as the most active Atlantic hurricane season on record. And, while we were otherwise distracted, 2020 also offered up near-record lows in Arctic sea ice, possible evidence of significant methane release from Arctic permafrost and the Arctic Ocean, huge wildfires in both the Amazon and the Arctic, shattered heat records (2020 rivaled 2016 for the hottest year on record), bleached coral reefs, the collapse of the last fully intact ice shelf in the Canadian Arctic, and increasing odds that the global climate system has passed the point where feedback dynamics take over and the window of possibility for preventing catastrophe closes.

President Biden has recommitted the United States to the Paris Agreement, which is great except that it doesn’t really mean much, since that agreement’s commitments are voluntary. And it might not even matter whether signatories meet their commitments, since their pledges weren’t rigorous enough to keep global warming “well below” two degrees Celsius, or 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit above preindustrial levels to begin with. According to Climate Action Tracker, a collaborative analysis from independent science nonprofits, only Morocco and Gambia have made commitments compatible with the goal of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels, and the commitments made by several major emitters, including China, Russia, Japan and the United States, are “highly insufficient” or “critically insufficient.”

It’s also worth noting that the two degrees Celsius benchmark is somewhat arbitrary and possibly fantastic, since it’s not clear that the earth’s climate would be safe or stable at that temperature. In the words of a widely discussed research summary published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, even if the Paris Agreement targets are met, “we cannot exclude the risk that a cascade of feedbacks could push the Earth System irreversibly onto a ‘Hothouse Earth’ pathway.”

More alarming, recent observed increases in atmospheric methane, a greenhouse gas more than 80 times stronger than carbon dioxide over the short term, are so large that if they continue they could effectively overwhelm the pledged emissions reductions in the Paris Agreement, even if those reductions were actually happening. Which they’re not.

Meanwhile, the earth’s climate seems to be changing faster than expected. Take the intensifying slowdown in the North Atlantic current, a global warming side effect made famous by the film “The Day After Tomorrow.” According to the climatologist Michael Mann, “We are 50 years to 100 years ahead of schedule with the slowdown of this ocean circulation pattern, relative to what the models predict … The more observations we get, the more sophisticated our models become, the more we’re learning that things can happen faster, and with a greater magnitude, than we predicted just years ago.”

In 2019, the Greenland ice sheet briefly reached daily melt rates predicted in what were once considered worst-case scenarios for 2060 to 2080. Recent research indicates that rapidly thawing permafrost may release twice as much carbon dioxide and methane than previously thought, which is pretty bad news, because other recent research shows very cold Arctic permafrost thawing 70 years earlier than expected.

Going back to normal now means returning to a course that will destabilize the conditions for all human life, everywhere on earth. Normal means more fires, more category 5 hurricanes, more flooding, more drought, millions upon millions more migrants fleeing famine and civil war, more crop failures, more storms, more extinctions, more record-breaking heat. Normal means the increasing likelihood of civil unrest and state collapse, of widespread agricultural failure and collapsing fisheries, of millions of people dying from thirst and hunger, of new diseases, old diseases spreading to new places and the havoc of war. Normal could well mean the end of global civilization as we know it.

I remember last March, in the first throes of the pandemic, when normal was upended. Everything shut down. We hoarded toilet paper and pasta. Fear gripped the nation.

I was afraid, too: I was afraid for my mother, who has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. I was afraid for my sister, whose husband works in a prison. I was afraid for my cousin, who’s a nurse. I was afraid for my country, under the leadership of an incompetent and seemingly deranged president.

But along with the fear, I remembered a lesson I’d learned in Iraq. I’d been a soldier in Baghdad in 2003-2004, where I saw what happens when the texture of the everyday is ripped apart. I realized that what we call social life was like a vast and complex game, with imaginary rules we all agreed to follow, fictions we turned into fact through institutions, stories, and daily repetition. Some of the rules were old, deeply ingrained and resilient. Some were so tenuous they’d barely survive a hard wind.

What I saw in Iraq was that every time you shock the system, something breaks. Sometimes those breaks never heal. There’s no way we can undo the damage we did to Iraq or bring back the lives lost to Covid. But sometimes those breaks are openings. Sometimes those breaks are opportunities to do things differently.

In March last year, watching an unknown plague stalk the land, I felt fear, but I also felt hope: the hope that this virus, as horrible as it might be, could also give us the chance to really understand and internalize the fragility and transience of our collective existence. I hoped we might recognize not only that fossil-fuel-driven consumer capitalism was likely to destroy everything we loved, but that we might actually be able to do something about it.

In March last year, watching an unknown plague stalk the land, I felt fear, but I also felt hope: the hope that this virus, as horrible as it might be, could also give us the chance to really understand and internalize the fragility and transience of our collective existence. I hoped we might recognize not only that fossil-fuel-driven consumer capitalism was likely to destroy everything we loved, but that we might actually be able to do something about it.

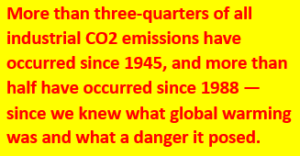

As the pandemic has worn on, the desire to get back to normal has increased, and I worry that the hope for radical positive change has subsided. But we must not let it dissipate. We can’t afford to. Because we won’t see “normal” again in our lifetimes. Our parents and grandparents burned normal up in their American-built cars, with their American lifestyles, their American refrigerators and American dreams. And now China and India are doing it, too, because capitalism is global, and we sold it wherever we could. More than three-quarters of all industrial CO2 emissions have occurred since 1945, and more than half have occurred since 1988 — since we knew what global warming was and what a danger it posed.

Now, as a new administration takes office and we look ahead to life after both Covid and Donald Trump, we need to face the fact that the world we live in is changing into something else, and that coping with the consequences of global warming demands immediate, widespread, radical action.

The next 20 years will be a period of deep uncertainty and tremendous risk, no matter what. We don’t get to choose what challenges we’ll face, but we do get to decide how we face them. The first thing we need to do is let go of the idea that life will ever be normal again — elsewhere, I’ve called this “learning how to die.” Beyond that, we need to stop living through social media and start connecting with the people around us, since those are the people we’ll need to depend on the next time disaster strikes. And disaster will strike, you can be sure of that, so we must begin preparing today for the next shock to the social order, and the next, and the next.

None of this will matter, though, if our preparations don’t include imagining a new way of life beyond this one, after the end of fossil-fueled capitalism: not a new normal, but a new ethos adapted to the chaotic world we’ve created.

Don’t Give Up On America, by Marilynne Robinson (Oct. 9)

This country is not just an idea. It’s a family.

Robinson, a winner of the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, is the author, most recently, of the novel “Jack.”

What does it mean to love a country? I have spent most of my life studying American history and literature because of a deep if sometimes difficult affinity I would call love. Deeper, though, is a feeling like a love of family, a hope that whoever by whatever accident or choice falls under the definition of family will thrive and will experience even a difficult life as a blessing because his or her worth is a fact without conditions.

A family would take practical steps to ease one another through hard times and to preserve the integrity of home as a special refuge. The honor of a family would consist in a very generous acknowledgment of claims on its loyalty and care.

It is often said that America is an idea, stated definitively in early documents left to us by a coterie of men seemingly too compromised to have come up with such glorious language — as we would be, too, if we should happen to achieve anything comparable. Human beings are sacred, therefore equal. We are asked to see one another in the light of a singular inalienable worth that would make a family of us if we let it.

The ethic in these words should be the standard by which we judge ourselves, our social arrangements, our dealings with the vast family of humankind. It will always find us wanting. The idea is a progressive force, constantly and necessarily exposing our failures and showing us new paths forward.

For some time we have been dealing with an active rejection of this idea. As a woman in her late 70s who saw the world before the movements for civil rights and women’s rights, I know how potent the idea of equality can be. There are those who find it threatening, who are so fearful of dealing with people of color, or with women, on equal terms that they fantasize about violence toward them, treating whole categories of their own people as deadly enemies.

They have translated anger and disappointment into rage against people of color, people of other opinions, the elites, the poor, even people whose very existence cannot be proved (so secretive are they!) but who are in sinister cahoots with Democrats and liberals. The policies of the other side may seem rational, practical, familiar, but their true nature is revealed in the fact that someone claims to have seen black-clad passengers on a commercial flight somewhere.

As a liberal, I am loyal to this country in ways that make me a pragmatist. If someone is hungry, feed him. He will be thirsty, so be sure that he has good water to drink. If he is in prison, don’t abuse, abandon or exploit him, or assume that he ought to be there. If these problems afflict whole populations, those with influence or authority should repent and do better, as all the prophets tell them.

As a liberal, I am loyal to this country in ways that make me a pragmatist. If someone is hungry, feed him. He will be thirsty, so be sure that he has good water to drink. If he is in prison, don’t abuse, abandon or exploit him, or assume that he ought to be there. If these problems afflict whole populations, those with influence or authority should repent and do better, as all the prophets tell them.

Over the past few years President Trump has promoted the belief that a large share of the American people are endlessly productive of plots, frauds and hoaxes, that they are not to be heard out in good faith, not to be acknowledged as enjoying the freedoms of the First Amendment.

This is the aspersion, the fraud, the hoax, most corrosive to democracy. Once a significant part of the population takes it to be true that other groups or classes do not participate legitimately in the political life of the country, democracy is in trouble. The public has no way to legitimize authority, which then becomes mere power.

Less than a month before the election, we have come to a place where every aspect of our electoral process is in doubt and at risk, threatened by suspicion and resentment now loose among our people to our great mutual harm. If the one civic exercise that gives legitimacy to our government defaults, we will, if we are honest, have to find a word other than “democracy” to describe whatever we will have become.

Resentment displaces hope and purpose the way carbon monoxide displaces air. This fact has been reflected in the policies of any number of tyrants and demagogues. Resentment is insatiable. It thrives on deprivation, sustaining itself by magnifying grievances it will, by its nature, never resolve.

At present we are told that America is being made great again, but specifics are hard to come by. It is true that, compared with the America of memory, little has been done recently to demonstrate modest foresight, let alone grand vision.

The failures of infrastructure can dim the spirits of people who deal with shabby schools or faulty bridges or who live downstream from a failing dam. Problems like these could be solved if there were the political will to solve them. It would feel good to see the old competence brought to bear again. Of course this would require investments of public money and the use of public money for the benefit of the public.

This is anathema to legislators who actually persuade their constituents that austerity, indiscriminate parsimony, is the highest good, whatever the consequences for public health or economic development. The cost of outright failure, in any specific instance or progressively and cumulatively, seems never to be factored in.

In place of better schools, with all the talent and aspiration education can unleash, it is cheaper to encourage a contempt for knowledge and for the “elites” who deal in it. If the small towns are dying out, encourage a hatred of the cities. In all cases, urge resentment of foreigners and immigrants. See the full force of our government deployed to terrorize a chicken factory.

Resentment is crucial to the drift away from reality that makes meaningful public life so difficult now. An especially pernicious form of suspicion, it thrives by insisting that no positive construction should ever be made of the thinking or the motives of the despised oppressors, that is, of those who are of another mind or another party. Their perfidy infects information in every form except for the shrieks and whispers to be found on the internet and the leggy and glossily profitable Fox News.

There is another source of inflamed unreality: the Trump White House.

There is another source of inflamed unreality: the Trump White House.

Donald Trump, the magister ludi, is a very odd duck. He has spent his long career demonstrating unreliability as a way of life, and he is embraced and trusted passionately by people who trust no one else. One man’s charlatan is the next man’s messiah, and we are witnessing a kind of staged resurrection that will harden both views of him.

He would like us to believe that Covid-19 has no power over him. He has broken its grip on his own person, demonstrating that his insouciant posture toward the pandemic was somehow right and those hundreds of thousands of deaths were a failure of will in the departed, or a lack of what he calls good genes.

How ill was the president to begin with? If he crashes after an apparent recovery, it will be within the range of expectations for the disease. Regardless, he has triggered another irresolvable dispute that will make him the center of attention during the run-up to the election, relieved of any expectation that he will propose policies like, for example, plans for health care or for infrastructure. This would be slippery and shrewd, that is, not improbable.

So we have, in the country’s highest office, a man who is at best an illusionist. He might talk about injecting disinfectant only to keep our minds off the children at the border. In other words, his bizarre ideas and behavior might be calculated to obscure his actual use of the powers of the presidency, which have grown in his hands till they have overwhelmed old concepts of limited government, of a balance of powers.

We do not know whether the president is blundering or scheming, sick or well. We do not know if he is trying, however ineptly, to bring the country through social, economic and political crisis or is using instability to heighten his power. Because he is erratic, we eye him carefully. We try to discern the limits of his excesses and vagaries, we watch his mood.

This is a president who holds grudges against our great cities. Mighty engines of wealth and culture that they are, this bankrupter of casinos wants to impose his will on them. He permits or refuses the public the benefits of institutions and resources that belong to us, converting government into patronage. This is a radical disempowerment of the people, accomplished through incompetence, chicanery and an absolute disrespect for the position he holds.

“Put not your trust in princes,” says the psalmist. “When his breath departs he returns to the earth; on that very day his plans perish.” We would also be wise, on these same grounds, not to despair over a political figure, either. Mr. Trump’s impact on so many areas of life is a product of his idiosyncrasy. We need not imagine that another faux businessman with a peculiar power to charm and repel, a virtual part of the living room furniture of many Americans over many years, will rise in his place. We do not even know what his plans are, of course, and the fact that he has created a cult of personality will inevitably narrow his effect in the longer term.

Leaders perish but the people have a relative immortality. Therefore the first order of business for us as a people is to find our way back to equilibrium. If Joe Biden wins, we will no doubt see in part a restoration of the old order. That order had many flaws and quarrels, but it had also, we now know, a loving deference toward the Constitution and the laws. If we learn anything from this sad passage in our history it should be that rage and contempt are a sort of neutron bomb in the marketplace of ideas, obviating actual competition. This country would do itself a world of good by restoring a sense of the dignity, even the beauty, of individual ethicalism, of self-restraint, of courtesy. These things might help us to like one another, even trust one another, both necessary to a functioning democracy.

Leaders perish but the people have a relative immortality. Therefore the first order of business for us as a people is to find our way back to equilibrium. If Joe Biden wins, we will no doubt see in part a restoration of the old order. That order had many flaws and quarrels, but it had also, we now know, a loving deference toward the Constitution and the laws. If we learn anything from this sad passage in our history it should be that rage and contempt are a sort of neutron bomb in the marketplace of ideas, obviating actual competition. This country would do itself a world of good by restoring a sense of the dignity, even the beauty, of individual ethicalism, of self-restraint, of courtesy. These things might help us to like one another, even trust one another, both necessary to a functioning democracy.

This country was, from the outset, a tremendous leap of faith. We tend not to ponder the brutality of the European world at the time our colonies formed and then fledged, so we have little or no idea of the radicalism not only of stating that “men,” as creatures of God, were equal, but of giving the idea profound political consequences by asserting for them unalienable rights, which were defined and elaborated in the Constitution. Our history to the present day is proof that people find justice hard to reach and to sustain. It is also proof that where justice is defined as equality, a thing never to be assumed, justice enlarges its own definition, pushing its margins in light of a better understanding of what equality should mean.

There is much to be done, more than inevitably limited people can see at a given moment. But the other side of our limitation is the fact that it carries with it a promise that we still might see a new birth of freedom, and another one beyond that. Democracy is the great instrument of human advancement. We have no right to fail it.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

There are no good choices, by Ezra Klein (Sept 14)

In shifting so much responsibility to individual people, America’s government has revealed the limits of individualism.

Klein, a co-founder of Vox, is editor-at-large there. He hosts the weekly podcast The Ezra Klein Show.

Where I live, the sky is choking. Wednesday was the worst. The day was a dark, burnt haze; red as the end of the world. My dogs paced and barked. The animal in me panicked, too. If the sky couldn’t breathe in the light, how were we to breathe in the air? My son is too young to wear a mask, too energetic to trap inside. How could I protect him? We wanted to flee, all of us. But where were we to go? We couldn’t shelter indoors, taking refuge with friends or family, because of the coronavirus. We couldn’t slip into nature because of the fire. There were no good choices.

This is the era of no good choices. Take schooling, for example. Keeping children home robs them of education and socialization. It scars their futures, steals their joys. It makes it impossible for their parents to work, or even to rest. But sending them to school endangers their health, and that of their teachers and their families. The argument is so heated because the choices are all bad, at least by the standards of the lives we used to lead. We battle like there is a good answer, like we will discover one side is right and the other is wrong. But we won’t. There is no answer. Whatever we pick, it will be horrible.

Everything is like that right now. Do you visit your parents, let them see their grandchild? How do you weigh the risk of contagion against the risk of isolation? If they’re sick, does that make visiting them more dangerous, or more necessary? How about your friends? What is the cost to your child of growing up without community, without other hands to take care of them, without other adults they’re allowed to hug, to play with? Do we reopen restaurants? If they do reopen, do we go to them? The risks are terrible, but so is the thought of losing an entire industry, of seeing all those dreams die, all those futures shatter. As the Senate dithers, these decisions are being left to us, and it is tearing us apart.

In America, our ideological conflicts are often understood as the tension between individual freedoms and collective actions. The failure of our pandemic response policy exposes the falseness of that frame. In the absence of effective state action, we, as individuals, find ourselves in prisons of risk, our every movement stalked by disease. We are anything but free; our only liberty is to choose among a menu of awful options. And faced with terrible choices, we are turning on each other, polarizing against one another. YouTube conspiracies and social media shaming are becoming our salves, the way we wrest a modicum of individual control over a crisis that has overwhelmed us as a collective.

“The burden of decision-making and risk in this pandemic has been fully transitioned from the top down to the individual,” says Dr. Julia Marcus, a Harvard epidemiologist. “It started with [responsibility] being transitioned to the states, which then transitioned it to the local school districts — If we’re talking about schools for the moment — and then down to the individual. You can see it in the way that people talk about personal responsibility, and the way that we see so much shaming about individual-level behavior.” (You can hear my whole conversation with Marcus on this podcast.)

But in shifting so much responsibility to individuals, our government has revealed the limits of individualism.

The risk calculation that rules, and ruins, lives

Think of coronavirus risk like an equation. Here’s a rough version of it: The danger of an act = (the transmission risk of the activity) x (the local prevalence of Covid-19) / (by your area’s ability to control a new outbreak).

Individuals can control only a small portion of that equation. People can choose safer activities over riskier ones — though the language of choice too often obscures the reality that many have no economic choice save to work jobs that put them, and their families, in danger. But the local prevalence of Covid-19 and the capacity of authorities to track and squelch outbreaks are collective functions. They rely on competent testing infrastructures, fast contact tracing, universal health insurance, thoughtful reopening policies, strong public health communication, reliable economic support for the displaced, and social trust. Managed well, they lower the background risk, making more activities safe enough to consider, making the decisions individuals face easier. But in America, that public infrastructure has failed most people, in most places. The result is a maddening world of risk that individuals have been left to navigate virtually alone.

Individuals can control only a small portion of that equation. People can choose safer activities over riskier ones — though the language of choice too often obscures the reality that many have no economic choice save to work jobs that put them, and their families, in danger. But the local prevalence of Covid-19 and the capacity of authorities to track and squelch outbreaks are collective functions. They rely on competent testing infrastructures, fast contact tracing, universal health insurance, thoughtful reopening policies, strong public health communication, reliable economic support for the displaced, and social trust. Managed well, they lower the background risk, making more activities safe enough to consider, making the decisions individuals face easier. But in America, that public infrastructure has failed most people, in most places. The result is a maddening world of risk that individuals have been left to navigate virtually alone.

In the absence of an effective public response, we turn our frustrations on each other, as we fail to navigate the impossible choices we’re left with. We shame each other for going to beaches, to protests, to bars, to schools. We’re angry at college kids attending parties and bikers attending rallies and runners who don’t don their masks as they speed by, each exhalation a threat to ourselves and those we love.

“The way that we get control of fear, which is driven by this sense of uncertainty, is we put the locus of control on individuals, because then we can be angry at people,” says Marcus.

Like everyone else, I have my views on which activities should be sanctioned and which should be shunned, but I also have my lapses, my compromises, my trade-offs. We all do. And as the pandemic wears on, those differences sharpen, cutting into even loving bonds. I know families being torn apart, and friendships and relationships fraying over differing views of risk and reward. Politics, too, is tipping into a darker, more dangerous place, with President Trump preemptively undermining the election, with millions out of work and furious at those they see as causing or dismissing their pain.

There are dozens of ways the government could make it easier for individuals to make safe choices, ranging from effective policies to control the spread of the virus to a renewed economic support package that would allow people to protect their health without sacrificing their livelihoods. This is how other countries are responding to the crisis, and it is working. But Trump has refused to put forward — much less follow — a plan to suppress the virus, and congressional Republicans have insisted on withdrawing support from the labor market, in a bid to force workers to return to jobs. In that way, the impossible choices being forced on Americans are a policy decision being made by their elected leaders.

We have been set up to fail

The closest thing the GOP has to an actual policy to suppress the virus was articulated by Vice President Mike Pence at the Republican National Convention. “America is a nation of miracles,” he said. “And I’m proud to report that we are on track to have the world’s first safe, effective coronavirus vaccine by the end of this year.” But even if that’s true — and that remains a big “if” — it does not mean the crisis will end, or that our former lives will resume, in the fall.

“Even if the vaccine were to come this fall, it would take us over a year to get the number of doses needed to vaccinate the population,” says Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota. “A year from now we’ll still be dealing with this situation. So I’m not here thinking about how to get through the next election. I’m thinking about how to get through the next few years.”

Imagine Joe Biden wins in November, and Democrats also take the Senate. What options will be open to them? Would the nation follow a lockdown, if one were needed? Would disappointed Trump voters heed a renewed push on masking, or would that simply feed the arcane phantasmagoria of QAnon? Are we prepared, socially and psychically, for a vaccine that fails, or even just disappoints? Will enough of us even trust a vaccine given the Trump administration’s relentless promotion of untested cures?

Imagine Joe Biden wins in November, and Democrats also take the Senate. What options will be open to them? Would the nation follow a lockdown, if one were needed? Would disappointed Trump voters heed a renewed push on masking, or would that simply feed the arcane phantasmagoria of QAnon? Are we prepared, socially and psychically, for a vaccine that fails, or even just disappoints? Will enough of us even trust a vaccine given the Trump administration’s relentless promotion of untested cures?

We have been set up to fail. Admitting that may, at some level, help us be more compassionate toward each other. We have been left without good choices, and so we are upset at the bad decisions our neighbors, friends, and families are making, even as they are angry at the trade-offs we choose. We are right to be upset. Our reality is enraging and terrifying. But more of our ire should be directed at the government that has left us in these straits.

Governmental failure has paved the way for social fracture. If the US government had succeeded as Canada or Germany’s governments succeeded, it would be easier to trust each other because we would pose less danger to each other. If we could depend more on the state, we could make more reasonable requests of ourselves. In the wreckage of state failure, though, it is nearly impossible for us to thrive.

This is a lesson the coronavirus is, or should be, teaching us, but it applies to far more than this moment. I began this column with the fires that have burnt my region; fires worsened, year after year, by unchecked climate change. There, too, our failures as a polity have left us adrift as individuals — free to flee our homes, but not free to breathe air that doesn’t leave us choking. It is a thin form of liberty, but it is all we will have left if we cannot govern collectively. We all want to be free to make our own choices. But we need government that works well enough so we have good choices to make.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Why the 2020 Election Makes It Hard to Be Optimistic About the Future

If we can’t face up to a pandemic, how can we avoid apocalypse?

By Paul Krugman, for The New York Times, Nov 16, 2020

The 2020 election is over. And the big winners were the coronavirus and, quite possibly, catastrophic climate change.

OK, democracy also won, at least for now. By defeating Donald Trump, Joe Biden pulled us back from the brink of authoritarian rule.

But Trump paid less of a penalty than expected for his deadly failure to deal with Covid-19, and few down-ballot Republicans seem to have paid any penalty at all. As a headline in The Washington Post put it, “With pandemic raging, Republicans say election results validate their approach.”

And their approach, in case you missed it, has been denial and a refusal to take even the most basic, low-cost precautions — like requiring that people wear masks in public.

The 2020 election is over. And the big winners were the coronavirus and, quite possibly, catastrophic climate change.

OK, democracy also won, at least for now. By defeating Donald Trump, Joe Biden pulled us back from the brink of authoritarian rule.

But Trump paid less of a penalty than expected for his deadly failure to deal with Covid-19, and few down-ballot Republicans seem to have paid any penalty at all. As a headline in The Washington Post put it, “With pandemic raging, Republicans say election results validate their approach.”

And their approach, in case you missed it, has been denial and a refusal to take even the most basic, low-cost precautions — like requiring that people wear masks in public.

Deaths from Covid-19 tend to run around three weeks behind new cases; given the exponential growth in cases since the early fall, which hasn’t slowed at all, this means that we may be looking at a daily death toll in the thousands by the end of the year. And remember, many of those who survive Covid-19 nonetheless suffer permanent health damage.

To be fair, the vaccine news has been very good, and it looks likely that we’ll finally bring the pandemic under control sometime next year. But we could suffer hundreds of thousands of American deaths, many of them avoidable, before the vaccine is widely distributed.

Awful as the pandemic outlook is, however, what worries me more is what our failed response says about prospects for dealing with a much bigger issue, one that poses an existential threat to civilization: climate change.

As many people have noted, climate change is an inherently difficult problem to tackle — not economically, but politically.

Right-wingers always claim that taking climate seriously would doom the economy, but the truth is that at this point the economics of climate action look remarkably benign. Spectacular progress in renewable energy technology makes it fairly easy to see how the economy can wean itself from fossil fuels. A recent analysis by the International Monetary Fund suggests that a “green infrastructure push” would, if anything, lead to faster economic growth over the next few decades.

But climate action remains very difficult politically given (a) the power of special interests and (b) the indirect link between costs and benefits.

Consider, for example, the problem posed by methane leaks from fracking wells. Better enforcement to limit these leaks would have huge benefits — but the benefits would be widely distributed across time and space. How do you get people in Texas to accept even a small rise in costs now when the payoff includes, say, a reduced probability of destructive storms a decade from now and half the world away?

This indirectness made many of us pessimistic about the prospects for climate action. But Covid-19 suggests that we weren’t pessimistic enough.

After all, the consequences of irresponsible behavior during a pandemic are vastly more obvious and immediate than the costs of climate inaction. Gather a bunch of unmasked people indoors — say, in the Trump White House — and you’re likely to see a spike in infections just a few weeks later. This spike will take place in your own neighborhood, quite possibly affecting people you know.

Furthermore, it’s a lot easier to discredit Covid deniers than it is to discredit climate-change deniers: All you have to do is point out the many, many times these deniers falsely asserted that the disease was about to go away.

So getting people to act responsibly on the coronavirus should be much easier than getting action on climate change. Yet what we see instead is widespread refusal to acknowledge the risks, accusations that cheap, common-sense rules like wearing masks constitute “tyranny,” and violent threats against public officials.

So what do you think will happen when the Biden administration tries to make climate a priority?

The one mitigating factor about the politics of climate policy I can see is that unlike fighting a pandemic, which is mainly about telling people what they can’t do, it should be possible to frame at least some climate action as carrots rather than sticks: investing in a green future and creating new jobs in the process, rather than simply requiring that people accept new limits and pay higher prices.

This is, by the way, possibly the biggest reason to hope that Democrats win those Georgia runoffs. Climate policy really needs to be sold as part of a package that also includes broader investment in infrastructure and job creation — and that just won’t happen if Mitch McConnell is still able to blockade legislation.

Obviously we need to keep trying to head off a climate apocalypse — and no, that’s not hyperbole. But even though the 2020 election wasn’t about climate, it was to some degree about the pandemic — and the results make it hard to be optimistic about the future.

Fighting the Virus in Trump’s Plague

My body is a stranger. It is out there battling the enemy within.

By Roger Cohen, for The New York Times, Sept 4, 2020

PARIS

A friend of mine opened her closet the other day and felt she was gazing at the clothes of a dead person. They belonged to the world of yesterday. She had no use for them in the age of the coronavirus. It was like looking at her grandmother’s clothes after she died.

Everyone is jolted these days in such ways. I assumed I would not get Covid-19 if I took basic precautions. Now I have Covid-19. My head feels like a cabbage. Aches swirl down my arms and legs. So please, dear reader, grant me a little indulgence this once.

My symptoms began Thursday Aug. 27, a sharp prickling in my throat, from nothing. A cabdriver said, “You are coughing, sir.” I said, I know, I am sorry, I am trying not to cough.

I am in a Paris apartment I have rented for a couple of weeks. On the bookshelves my eyes fell on a copy of Stefan Zweig’s “The World of Yesterday,” written in Brazil before he and his wife, Charlotte Altmann, committed suicide in 1942. A Viennese Jew born into an empire that no longer existed, his books burned in a Europe reduced to barbarism, Zweig wrote: “All the livid steeds of the Apocalypse have stormed through my life.”

A day later my symptoms worsened. I had a fever of 101. Hot flushes, and shivers, alternated. My mind swirled. So, this is it. The plague that stopped the world. I was more curious than afraid. It’s hard to shed the reflexes of a life lived as an observer.

Since the pandemic started, I have wondered, like everybody, how to live. “Stay safe” is no guide to a life worth living. Surrender to fear and it’s over. My most powerful memories and experiences involved risk. When you quit, you’re done. Yet now an invisible enemy demanded prudence.

For more than three months I scarcely moved from my Brooklyn neighborhood. I mourned New York. I tried to get used to the end of conviviality and the way “coronavirus” slips from the tongues of my five grandchildren, aged 2 to 6.

I tried and failed. Still, we have to get on with it, show up. That’s life’s first admonition. I drove to Georgia, did some reporting, and wrote. I came to Europe to look and listen.

Zweig’s book fell open at this: “I have seen the great mass ideologies grow and spread before my eyes — Fascism in Italy, National Socialism in Germany, Bolshevism in Russia, and above all else that pestilence of pestilences, nationalism, which has poisoned the flower of our European culture.”

My president, Donald Trump, is a proud nationalist. He embraces its mythology of violence as he flirts with cataclysm. Jump! he says. How high? says his cabinet. He’s ready to fight his battles down to the last sucker. If he goes down, it will be in flames.

The virus is deadly serious but plays games. A little relief to tempt you into activity — then it smites you with a cudgel. I felt better last weekend until I tried a peach tart. It’s eerie to experience texture without taste. A Coke with ice and lemon was no more than fizz. My body was a stranger. It was out there somewhere, fighting. The fight demanded all its energy. There was nothing left for me.

I stared at the walls. I thought, my world is gone. More than half a life lived in the Cold War, who cares about that any longer, or the values it bequeathed. A phrase of Albert Camus came back to me: “The most incorrigible vice being that of ignorance that fancies it knows everything and therefore claims for itself the right to kill.”

For three hours I lined up for a free coronavirus test. A medic told me the swab in my nostrils would be “disagreeable but not painful.” She then stabbed my brain with what looked like a narrow brochette stick. “That was painful,” I said.

My test result, received two days later, was “positive.” I knew it would be, but still reading the lab result was hard. I am not sure why. Perhaps the certain knowledge that a virus is inside you that could kill you. But then so many things can, and death is life’s one certainty — and we don’t stop the world. We try to make life better. The only way out of this is through.

The plague is back. In fact, as Camus observed, it never goes away. It is waiting to exploit stupidity. Trump wants violence. Do not give it to him. Turn the other cheek. Be stoical. Be the person who stops the tank by standing there.

I am hunkered down. My survival chances are still better than those of an opposition leader in the Russia of Trump’s buddy. My daughter and her husband, both doctors, say I have a moderate case. I think I picked it up in a crowded Paris bar watching a soccer match. Whether soccer or life is more important is an open question to me.

The epigraph to Zweig’s book is a quote from Shakespeare’s “Cymbeline”:

“And meet the time as it seeks us.”

I will still try to do that. We must all fight, in the way my body is fighting now with every ounce of its strength to see off the enemy within, if the orange face of the plague is not to devour us all.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Coronavirus Is Rewriting Our Imaginations, by Kim Stanley Robinson (May 1)

What felt impossible has become thinkable. The spring of 2020 is suggestive of how much, and how quickly, we can change as a civilization.

This penetrating, lyrical article in The New Yorker magazine by celebrated speculative-fiction writer Robinson (Mars Trilogy, New York 2140 and many other works) offers cautious optimism that the new “structure of feeling” sparked by the pandemic might lead humanity to finally address climate change with full force.

The critic Raymond Williams once wrote that every historical period has its own “structure of feeling.” How everything seemed in the nineteen-sixties, the way the Victorians understood one another, the chivalry of the Middle Ages, the world view of Tang-dynasty China: each period, Williams thought, had a distinct way of organizing basic human emotions into an overarching cultural system. Each had its own way of experiencing being alive.

In mid-March, in a prior age, I spent a week rafting down the Grand Canyon. When I left for the trip, the United States was still beginning to grapple with the reality of the coronavirus pandemic. Italy was suffering; the N.B.A. had just suspended its season; Tom Hanks had been reported ill. When I hiked back up, on March 19th, it was into a different world. I’ve spent my life writing science-fiction novels that try to convey some of the strangeness of the future. But I was still shocked by how much had changed, and how quickly.

Schools and borders had closed; the governor of California, like governors elsewhere, had asked residents to begin staying at home. But the change that struck me seemed more abstract and internal. It was a change in the way we were looking at things, and it is still ongoing. The virus is rewriting our imaginations. What felt impossible has become thinkable. We’re getting a different sense of our place in history. We know we’re entering a new world, a new era. We seem to be learning our way into a new structure of feeling.

In many ways, we’ve been overdue for such a shift. In our feelings, we’ve been lagging behind the times in which we live. The Anthropocene, the Great Acceleration, the age of climate change — whatever you want to call it, we’ve been out of synch with the biosphere, wasting our children’s hopes for a normal life, burning our ecological capital as if it were disposable income, wrecking our one and only home in ways that soon will be beyond our descendants’ ability to repair. And yet we’ve been acting as though it were 2000, or 1990 — as though the neoliberal arrangements built back then still made sense. We’ve been paralyzed, living in the world without feeling it.

Now, all of a sudden, we’re acting fast as a civilization. We’re trying, despite many obstacles, to flatten the curve — to avoid mass death. Doing this, we know that we’re living in a moment of historic importance. We realize that what we do now, well or badly, will be remembered later on. This sense of enacting history matters. For some of us, it partly compensates for the disruption of our lives.

Actually, we’ve already been living in a historic moment. For the past few decades, we’ve been called upon to act, and have been acting in a way that will be scrutinized by our descendants. Now we feel it. The shift has to do with the concentration and intensity of what’s happening. September 11th was a single day, and everyone felt the shock of it, but our daily habits didn’t shift, except at airports; the President even urged us to keep shopping. This crisis is different. It’s a biological threat, and it’s global. Everyone has to change together to deal with it. That’s really history.

Actually, we’ve already been living in a historic moment. For the past few decades, we’ve been called upon to act, and have been acting in a way that will be scrutinized by our descendants. Now we feel it. The shift has to do with the concentration and intensity of what’s happening. September 11th was a single day, and everyone felt the shock of it, but our daily habits didn’t shift, except at airports; the President even urged us to keep shopping. This crisis is different. It’s a biological threat, and it’s global. Everyone has to change together to deal with it. That’s really history.

It seems as though science has been mobilized to a dramatic new degree, but that impression is just another way in which we’re lagging behind. There are 7.8 billion people alive on this planet — a stupendous social and technological achievement that’s unnatural and unstable. It’s made possible by science, which has already been saving us. Now, though, when disaster strikes, we grasp the complexity of our civilization — we feel the reality, which is that the whole system is a technical improvisation that science keeps from crashing down.

On a personal level, most of us have accepted that we live in a scientific age. If you feel sick, you go to a doctor, who is really a scientist; that scientist tests you, then sometimes tells you to take a poison so that you can heal — and you take the poison. It’s on a societal level that we’ve been lagging. Today, in theory, everyone knows everything. We know that our accidental alteration of the atmosphere is leading us into a mass-extinction event, and that we need to move fast to dodge it. But we don’t act on what we know. We don’t want to change our habits. This knowing-but-not-acting is part of the old structure of feeling.

Now comes this disease that can kill anyone on the planet. It’s invisible; it spreads because of the way we move and congregate. Instantly, we’ve changed. As a society, we’re watching the statistics, following the recommendations, listening to the scientists. Do we believe in science? Go outside and you’ll see the proof that we do everywhere you look. We’re learning to trust our science as a society. That’s another part of the new structure of feeling.

Possibly, in a few months, we’ll return to some version of the old normal. But this spring won’t be forgotten. When later shocks strike global civilization, we’ll remember how we behaved this time, and how it worked. It’s not that the coronavirus is a dress rehearsal — it’s too deadly for that. But it is the first of many calamities that will likely unfold throughout this century. Now, when they come, we’ll be familiar with how they feel.

What shocks might be coming? Everyone knows everything. Remember when Cape Town almost ran out of water? It’s very likely that there will be more water shortages. And food shortages, electricity outages, devastating storms, droughts, floods. These are easy calls. They’re baked into the situation we’ve already created, in part by ignoring warnings that scientists have been issuing since the nineteen-sixties. Some shocks will be local, others regional, but many will be global, because, as this crisis shows, we are interconnected as a biosphere and a civilization.

What shocks might be coming? Everyone knows everything. Remember when Cape Town almost ran out of water? It’s very likely that there will be more water shortages. And food shortages, electricity outages, devastating storms, droughts, floods. These are easy calls. They’re baked into the situation we’ve already created, in part by ignoring warnings that scientists have been issuing since the nineteen-sixties. Some shocks will be local, others regional, but many will be global, because, as this crisis shows, we are interconnected as a biosphere and a civilization.

Imagine what a food scare would do. Imagine a heat wave hot enough to kill anyone not in an air-conditioned space, then imagine power failures happening during such a heat wave. (The novel I’ve just finished begins with this scenario, so it scares me most of all.) Imagine pandemics deadlier than the coronavirus. These events, and others like them, are easier to imagine now than they were back in January, when they were the stuff of dystopian science fiction. But science fiction is the realism of our time. The sense that we are all now stuck in a science-fiction novel that we’re writing together — that’s another sign of the emerging structure of feeling.

Science-fiction writers don’t know anything more about the future than anyone else. Human history is too unpredictable; from this moment, we could descend into a mass-extinction event or rise into an age of general prosperity. Still, if you read science fiction, you may be a little less surprised by whatever does happen. Often, science fiction traces the ramifications of a single postulated change; readers co-create, judging the writers’ plausibility and ingenuity, interrogating their theories of history. Doing this repeatedly is a kind of training. It can help you feel more oriented in the history we’re making now. This radical spread of possibilities, good to bad, which creates such a profound disorientation; this tentative awareness of the emerging next stage — these are also new feelings in our time.

Memento mori: remember that you must die. Older people are sometimes better at keeping this in mind than younger people. Still, we’re all prone to forgetting death. It never seems quite real until the end, and even then it’s hard to believe. The reality of death is another thing we know about but don’t feel.

So this epidemic brings with it a sense of panic: we’re all going to die, yes, always true, but now perhaps this month! That’s different. Sometimes, when hiking in the Sierra, my friends and I get caught in a lightning storm, and, completely exposed to it, we hurry over the rocky highlands, watching lightning bolts crack out of nowhere and connect nearby, thunder exploding less than a second later. That gets your attention: death, all too possible! But to have that feeling in your ordinary, daily life, at home, stretched out over weeks — that’s too strange to hold on to. You partly get used to it, but not entirely. This mixture of dread and apprehension and normality is the sensation of plague on the loose. It could be part of our new structure of feeling, too.

Just as there are charismatic megafauna, there are charismatic mega-ideas. “Flatten the curve” could be one of them. Immediately, we get it. There’s an infectious, deadly plague that spreads easily, and, although we can’t avoid it entirely, we can try to avoid a big spike in infections, so that hospitals won’t be overwhelmed and fewer people will die. It makes sense, and it’s something all of us can help to do. When we do it — if we do it — it will be a civilizational achievement: a new thing that our scientific, educated, high-tech species is capable of doing. Knowing that we can act in concert when necessary is another thing that will change us.

Just as there are charismatic megafauna, there are charismatic mega-ideas. “Flatten the curve” could be one of them. Immediately, we get it. There’s an infectious, deadly plague that spreads easily, and, although we can’t avoid it entirely, we can try to avoid a big spike in infections, so that hospitals won’t be overwhelmed and fewer people will die. It makes sense, and it’s something all of us can help to do. When we do it — if we do it — it will be a civilizational achievement: a new thing that our scientific, educated, high-tech species is capable of doing. Knowing that we can act in concert when necessary is another thing that will change us.

People who study climate change talk about “the tragedy of the horizon.” The tragedy is that we don’t care enough about those future people, our descendants, who will have to fix, or just survive on, the planet we’re now wrecking. We like to think that they’ll be richer and smarter than we are and so able to handle their own problems in their own time. But we’re creating problems that they’ll be unable to solve. You can’t fix extinctions, or ocean acidification, or melted permafrost, no matter how rich or smart you are. The fact that these problems will occur in the future lets us take a magical view of them. We go on exacerbating them, thinking — not that we think this, but the notion seems to underlie our thinking — that we will be dead before it gets too serious. The tragedy of the horizon is often something we encounter, without knowing it, when we buy and sell. The market is wrong; the prices are too low. Our way of life has environmental costs that aren’t included in what we pay, and those costs will be borne by our descendents. We are operating a multigenerational Ponzi scheme.

And yet: “Flatten the curve.” We’re now confronting a miniature version of the tragedy of the time horizon. We’ve decided to sacrifice over these months so that, in the future, people won’t suffer as much as they would otherwise. In this case, the time horizon is so short that we are the future people. It’s harder to come to grips with the fact that we’re living in a long-term crisis that will not end in our lifetimes. But it’s meaningful to notice that, all together, we are capable of learning to extend our care further along the time horizon. Amid the tragedy and death, this is one source of pleasure. Even though our economic system ignores reality, we can act when we have to. At the very least, we are all freaking out together. To my mind, this new sense of solidarity is one of the few reassuring things to have happened in this century. If we can find it in this crisis, to save ourselves, then maybe we can find it in the big crisis, to save our children and theirs.

And yet: “Flatten the curve.” We’re now confronting a miniature version of the tragedy of the time horizon. We’ve decided to sacrifice over these months so that, in the future, people won’t suffer as much as they would otherwise. In this case, the time horizon is so short that we are the future people. It’s harder to come to grips with the fact that we’re living in a long-term crisis that will not end in our lifetimes. But it’s meaningful to notice that, all together, we are capable of learning to extend our care further along the time horizon. Amid the tragedy and death, this is one source of pleasure. Even though our economic system ignores reality, we can act when we have to. At the very least, we are all freaking out together. To my mind, this new sense of solidarity is one of the few reassuring things to have happened in this century. If we can find it in this crisis, to save ourselves, then maybe we can find it in the big crisis, to save our children and theirs.

Margaret Thatcher said that “there is no such thing as society,” and Ronald Reagan said that “government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.” These stupid slogans marked the turn away from the postwar period of reconstruction and underpin much of the bullshit of the past forty years.

We are individuals first, yes, just as bees are, but we exist in a larger social body. Society is not only real; it’s fundamental. We can’t live without it. And now we’re beginning to understand that this “we” includes many other creatures and societies in our biosphere and even in ourselves. Even as an individual, you are a biome, an ecosystem, much like a forest or a swamp or a coral reef. Your skin holds inside it all kinds of unlikely coöperations, and to survive you depend on any number of interspecies operations going on within you all at once. We are societies made of societies; there are nothing but societies. This is shocking news — it demands a whole new world view. And now, when those of us who are sheltering in place venture out and see everyone in masks, sharing looks with strangers is a different thing. It’s eye to eye, this knowledge that, although we are practicing social distancing as we need to, we want to be social — we not only want to be social, we’ve got to be social, if we are to survive. It’s a new feeling, this alienation and solidarity at once. It’s the reality of the social; it’s seeing the tangible existence of a society of strangers, all of whom depend on one another to survive. It’s as if the reality of citizenship has smacked us in the face.

As for government: it’s government that listens to science and responds by taking action to save us. Stop to ponder what is now obstructing the performance of that government. Who opposes it? Right now we’re hearing two statements being made. One, from the President and his circle: we have to save money even if it costs lives. The other, from the Centers for Disease Control and similar organizations: we have to save lives even if it costs money. Which is more important, money or lives? Money, of course! says capital and its spokespersons. Really? people reply, uncertainly. Seems like that’s maybe going too far? Even if it’s the common wisdom? Or was.

Some people can’t stay isolated and still do their jobs. If their jobs are important enough, they have to expose themselves to the disease. My younger son works in a grocery store and is now one of the front-line workers who keep civilization running.

My son is now my hero: this is a good feeling. I think the same of all the people still working now for the sake of the rest of us. If we all keep thinking this way, the new structure of feeling will be better than the one that’s dominated for the past forty years.

The neoliberal structure of feeling totters. What might a post-capitalist response to this crisis include? Maybe rent and debt relief; unemployment aid for all those laid off; government hiring for contact tracing and the manufacture of necessary health equipment; the world’s militaries used to support health care; the rapid construction of hospitals.

What about afterward, when this crisis recedes and the larger crisis looms? If the project of civilization — including science, economics, politics, and all the rest of it — were to bring all eight billion of us into a long-term balance with Earth’s biosphere, we could do it. By contrast, when the project of civilization is to create profit — which, by definition, goes to only a few — much of what we do is actively harmful to the long-term prospects of our species. Everyone knows everything. Right now pursuing profit as the ultimate goal of all our activities will lead to a mass-extinction event. Humanity might survive, but traumatized, interrupted, angry, ashamed, sad. A science-fiction story too painful to write, too obvious. It would be better to adapt to reality.

Economics is a system for optimizing resources, and, if it were trying to calculate ways to optimize a sustainable civilization in balance with the biosphere, it could be a helpful tool. When it’s used to optimize profit, however, it encourages us to live within a system of destructive falsehoods. We need a new political economy by which to make our calculations. Now, acutely, we feel that need.

It could happen, but it might not. There will be enormous pressure to forget this spring and go back to the old ways of experiencing life. And yet forgetting something this big never works. We’ll remember this even if we pretend not to. History is happening now, and it will have happened. So what will we do with that?

It could happen, but it might not. There will be enormous pressure to forget this spring and go back to the old ways of experiencing life. And yet forgetting something this big never works. We’ll remember this even if we pretend not to. History is happening now, and it will have happened. So what will we do with that?

A structure of feeling is not a free-floating thing. It’s tightly coupled with its corresponding political economy. How we feel is shaped by what we value, and vice versa. Food, water, shelter, clothing, education, health care: maybe now we value these things more, along with the people whose work creates them. To survive the next century, we need to start valuing the planet more, too, since it’s our only home.

It will be hard to make these values durable. Valuing the right things and wanting to keep on valuing them — maybe that’s also part of our new structure of feeling. As is knowing how much work there is to be done. But the spring of 2020 is suggestive of how much, and how quickly, we can change. It’s like a bell ringing to start a race. Off we go — into a new time.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

From Climate to Covid, and Back Again, by Andrew Ratzkin (May 2)

In this op-ed published in the Albany Times-Union as Virus’ collective threat, the author, an energy-sector lawyer who serves on the Westchester County Climate Smart Communities Task Force, draws lessons for climate challenges from the Covid pandemic.

No one’s talking much about climate change lately. We have a lot on our minds.

But climate’s not going away as an issue, even though emissions have temporarily dropped steeply. The climate will not stop warming, and spillover effects will not stop coming, just because we are distracted dealing with coronavirus.

The coronavirus was not caused by climate. Still, there are important things we can learn from the virus, and maybe have already learned, that can make a difference in how we approach climate once we are again able to focus on other things.

The coronavirus’ spread and impact reveal critical shortcomings in our preparedness, and offer important lessons, directly relevant to the climate challenges to come:

Cognitive Dissonance and Magical Thinking. It’s hard to envision and take seriously things that seems distant and intangible. It’s harder still to confront a long-term, collective threat from an inanimate adversary, especially while you’re still comfortable.

Like climate change, a pandemic once seemed to many like something that was “never going to happen” — until it did. Coronavirus awakens us to the possibility that bad things (and worst case scenarios) can actually happen. Long-term things eventually become short-term, immediate things.

Facts Matter, Science Matters. Science can tell us stuff. Science helps us detect and solve actual problems. Self-serving or delusional spin can actually hurt us, even though bravado makes for good TV. Spin — believing it and acting on it — is dangerous.

Expertise Matters. We need to listen to people who have studied problems that are not obvious without study. We don’t have to uncritically accept everything experts tell us. But we should respect them, hear their analyses and warnings, and factor them into our decisions.

Prevention Matters, Preparedness Matters. We hear how expensive it is to control greenhouse gas emissions, to convert our economy so that it is not powered by fossil fuels, to build a climate-resilient infrastructure. Just like we’ve heard how expensive it was to maintain the pandemic unit at the National Security Council. But maybe we have learned that the cost of an exacerbated crisis far exceeds the cost of reckoning with one ahead of time.

Follow-on Effects Happen. The coronavirus caused stocks and the economy to crash. It will cause untold cultural changes. What do we think will happen when climate change really starts to bite? And, unlike coronavirus, climate effects won’t present as a short-term, albeit painful, blip. When climate change hits in a big way — say, the irreversible flooding of a major city — what will be the follow-on effects for the stock market, the economy, mass migration, conflict? Consequences can be as severe, or more so, than the initial cause.

Some Problems Are Global. If coronavirus couldn’t be prevented from reaching our shores, what about changes in the climate? Global problems require global solutions and international cooperation.

Politics Can Change Fast. Look how fast the Trump administration shifted from denying that the coronavirus was anything more than a liberal media hoax to relishing a “wartime” presidency. Look how fast the Republican Senate became a hotbed of Keynesianism.

Maybe, just maybe, the suspicion that, just like coronavirus, climate is not a hoax after all, nor a conspiracy serving a political agenda, will open some minds. Maybe more will listen to calls to redouble our efforts to prevent as much of the impending climate crisis as we can, and to take measures needed to prepare for what we can’t. For now, for the most part, climate change is still out there as something that will happen “one day.” But that day will arrive, when something happens so terrible that everyone will at last know it’s for real. When that day comes, will we be ready?

Of course, the climate crisis won’t actually arrive “one” day. It’s already here, if not quite yet in a form — despite wildfires, dying coral reefs, melting glaciers, changes to planting seasons, more frequent and extreme hurricanes, droughts and deluges — that evokes universal recognition.

The coronavirus will one day be behind us; the warming already baked into the atmosphere will make itself felt for decades and centuries. In that key sense, climate change is very different.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

After Alarmism: The war on climate denial has been won. And that’s not the only good news.

By David Wallace-Wells, reprinted from New York magazine, Jan. 18-31, 2021.

In the American Southwest, birds fell dead from the sky by the tens of thousands, succumbing mid-flight to starvation, emaciated by climate change.

Across the horn of Africa swarmed 200 billion locusts, 25 for every human on earth, darkening the sky in clouds as big as whole cities, descending on cropland and chewing through as much food as tens of millions of people eat in a day, eventually dying in such agglomerating mounds they stopped trains in their tracks — all told, 8,000 times as many locusts as could be expected in the absence of warming.

The fires, you know. Or do you? In California in 2020, twice as much land burned as had ever burned before in any year in the modern history of the state — five of the six biggest fires ever recorded. In Siberia, “zombie fires” smoldered anomalously all through the Arctic winter; in Brazil, a quarter of the Pantanal, the world’s largest wetland, was incinerated; in Australia, flames took the lives of 3 billion animals.

All year, a planet transformed by the burning of carbon discharged what would have once been called portents of apocalypse. The people of that planet, as a whole, didn’t take much notice — distracted by the pandemic and trained, both by the accumulating toll of recent disasters and the ever-rising volume of climate alarm, to see what might once have looked like brutal ruptures in lived reality instead as logical developments in a known pattern. Our time has been so stuffed with disasters that it was hard to see the arrival of perhaps the unlikeliest prophecy of all: that the plague year may have marked, for climate change, a turning point, and for the better.

When trying to share good news about climate, it pays to be cautious, since so many have looked foolish playing Pollyanna. A turning point isn’t an endgame, or a victory, or a cessation of the need to struggle — for speedier decarbonization, for a sturdier future, for climate justice. Already, a future without profound climate suffering has been almost certainly foreclosed by decades of inaction, which means the burden of managing those impacts equitably will be handed down, generation to generation, into an indefinite and contested climate future.

But if the arrival of Joe Biden in the White House feels like something of a fresh start, well, to a degree it is. The world’s most conspicuous climate villain has been deposed, and though Biden was hardly the first choice of environmentalists, his victory signals an effective end to the age of denial and the probable beginning of a new era of climate realism, with fights for progress shaped as much by choices as by first principles.

The change is much bigger than the turnover of American leadership. By the time the Biden presidency finds its footing in a vaccinated world, the bounds of climate possibility will have been remade. Just a half-decade ago, it was widely believed that a “business as usual” emissions path would bring the planet four or five degrees of warming — enough to make large parts of Earth effectively uninhabitable. Now, thanks to the rapid death of coal, the revolution in the price of renewable energy, and a global climate politics forged by a generational awakening, the expectation is for about three degrees. Recent pledges could bring us closer to two. All of these projections sketch a hazardous and unequal future, and all are clouded with uncertainties — about the climate system, about technology, about the dexterity and intensity of human response, about how inequitably the most punishing impacts will be distributed. Yet if each half-degree of warming marks an entirely different level of suffering, we appear to have shaved a few of them off our likeliest end stage in not much time at all.

The next half-degrees will be harder to shave off, and the most crucial increment — getting from two degrees to 1.5 — perhaps impossible, dashing the dream of avoiding what was long described as “catastrophic” change. But for a climate alarmist like me, seeing clearly the state of the planet’s future now requires a conspicuous kind of double vision, in which a guarded optimism seems perhaps as reasonable as panic. Given how long we’ve waited to move, what counts now as a best-case outcome remains grim. It also appears, miraculously, within reach.

In December, a month after Biden was elected promising to return the U.S. to the Paris agreement, the U.N. celebrated five years since the signing of those accords. They were five of the six hottest on record. (The sixth was 2015, the year the agreement was signed.) They were also the years with the highest levels of carbon output in the history of humanity — with emissions equivalent to what was produced by all human and industrial activity from the speciation of Homo sapiens to the start of World War II.

They have also been the five years in which the nations of the world — and cities and regions, individuals and institutions, corporations and central banks — have made the most ambitious pledges of future climate action. Most of them were made in the past 12 months, in the face of the pandemic. Or, perhaps, to some degree, because of it — because the pandemic demanded a full-body jolt to the global political economy, provoking much more aggressive government spending, a much more accommodating perspective on debt, and a much greater openness to large-scale actions and investments of the kind that might plausibly reshape the world. And because decarbonization has come to seem, even to those economists and policy-makers blinded for decades to the moral and humanitarian cases for reform, a rational investment. “When I think about climate change,” Biden is fond of saying, “the word I think of is jobs.”

There are two ways of looking at these seemingly contradictory sets of facts. The first is that the distance between what is being done and what needs to be done is only growing. This is the finding of, among others, the U.N.’s comprehensive “Emissions Gap” report, issued in December, which found that staying below two degrees of warming would require a tripling of stated ambitions. To bring the planet in reach of the 1.5-degree target — favored by activists, most scientists, and really anyone reading their work with open eyes — would require a quintupling. It is also the perspective of Greta Thunberg, who has spent the pandemic year castigating global leaders for paying mere lip service to far-off decarbonization targets and who called the E.U.’s new net-zero emissions law “surrender.”

The second is that all of the relevant curves are bending — too slowly but nevertheless in the right direction. The International Energy Agency, a notoriously conservative forecaster, recently called solar power “the cheapest electricity in history” and projected that India will build 86 percent less new coal power capacity than it thought just one year ago. Today, business as usual no longer means a fivefold increase of coal use this century, as was once expected. It means pretty rapid decarbonization, at least by the standards of history, in which hardly any has ever taken place before.