Since the 1970s, energy-efficiency regulations (generally called “standards”) on appliances, vehicles and buildings have helped save large amounts of electricity and fuel in the United States, largely by forcing product design changes that would not have come about from “market forces” alone.

But energy standards by themselves will never achieve the deep cuts in energy usage needed for the clean-energy transition. Standard-setting takes a long time and invariably involves compromises with powerful industries (automobiles, consumer durables) that lead to confusing and wasteful loopholes. Moreover, standards by nature can handle only one product or usage-sector at a time and tend to be static whereas energy use is ever-evolving, especially in dynamic and “disruptive” late capitalism. In addition, standards provide no incentive for users (drivers, households) to change their behavioral patterns to maximize energy savings.

Carbon taxes combined with efficiency standards will achieve far more than standards alone by encouraging manufacturers and builders to proactively maximize energy efficiency while giving consumers ongoing incentives to make cost-effective choices valuing efficiency in shopping, traveling and purchase of homes and other durables.

We made many of these points in a blog post in September 2015, What an Energy-Efficiency Hero Gets Wrong about Carbon Taxes, from September, 2015. It was one of our most popular posts, and we reproduce it directly below. We hope to add content soon about the limits of automobile mpg standards.

— Charles Komanoff, November 2015

What an Energy-Efficiency Hero Gets Wrong about Carbon Taxes (from Sept 2015)

It’s rare that critiques of carbon taxing are as quantitative as the post last month by David Goldstein on the Natural Resource Defense Council’s Searchlight blog.

Goldstein qualifies as a genuine energy-efficiency hero, in my book. He has spearheaded NRDC’s pioneering analyses of appliance engineering, manufacture and marketing since the 1970s and guided the council’s strategic interventions in utility governance and energy standard-setting in California and at the federal level. This in-the-trenches work has slashed power consumption and carbon emissions from refrigerators, air conditioners, light bulbs and building envelopes in all 50 states. Goldstein’s 2002 MacArthur Foundation “genius award” was richly deserved. (The Washington DC-based American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, ACEEE, merits a shout-out as well.)

Befitting his analytical bent, Goldstein’s critique sticks to the high road. No self-fulfilling taunts about carbon taxers’ naivete or the tax’s political infeasibility. His post does drag out a straw man, though, insisting up-front that “carbon emissions fees alone cannot solve the climate problem” — a position held by few carbon tax advocates. (We ourselves “recommend carbon taxes in addition to energy–efficiency standards.”) His criticism sharpens at the end: “In summary, carbon pollution fees, as a stand-alone policy, are incapable of doing much to solve the climate problem.”

Goldstein has certainly thrown down the gauntlet. He has four main arguments, which I’ll treat in order. Some math is involved, but it’s central to the issue.

Argument #1: Carbon Taxes Must Raise U.S. Energy Prices 44-Fold to Meet Our Carbon Targets

Let’s start with an assertion by Goldstein that is startling but accurate — mathematically:

If we wanted energy demand to drop by 85 percent [the minimum required for the U.S. to meet IPCC temperature-rise targets] due to price, the math behind elasticities shows that we would require a price increase of 44 times. This is an impossibility condition. (emphasis added)

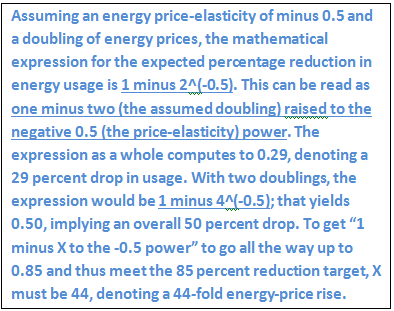

Price-elasticity is how economists denote the extent to which a rise in price causes demand or usage of a good or service to diminish. Assuming, as Goldstein does for argument’s sake (and as we do in modeling carbon taxes), that the price-elasticities of the various forms in which energy is used in the U.S. have an average value of minus 0.5, then a doubling of energy prices, whether effected through a carbon tax or market fluctuations, will cause energy use over time to shrink by 29 percent. (See sidebar for calculations.) With two doublings in price, the shrinkage would be 50 percent.

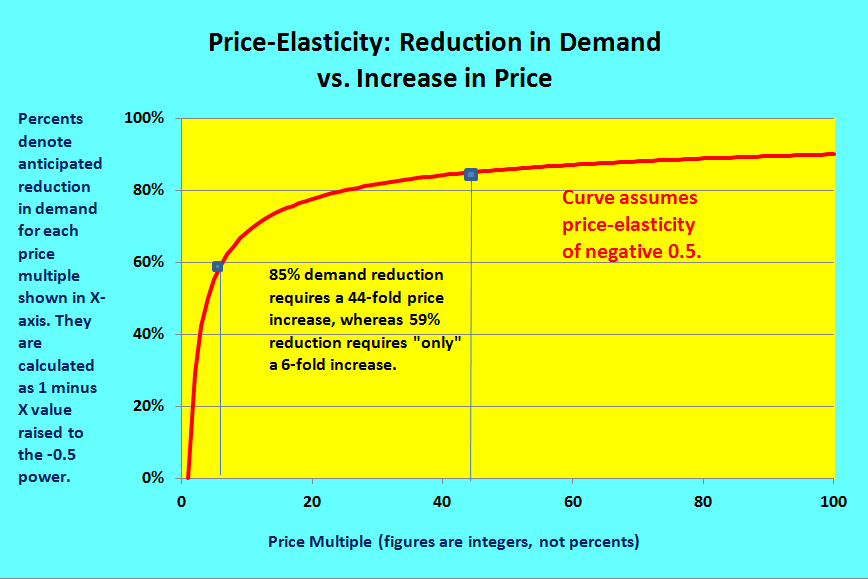

Note that the second doubling in price produces less of a decrease in usage than the first, reflecting the famed Law of Diminishing Returns. Indeed, three doublings, increasing the price 8-fold, would only bring about an overall 65 percent drop in usage. To hit the 85 percent reduction target requires a 44-fold energy-price rise. Goldstein’s math is spot-on.

But not the use to which it is put. While an 85 percent reduction in energy use would indeed cure the United States’ carbon obligations (not to mention protect and conserve air, water and land), it far exceeds what’s required, thanks to the ongoing and parallel reduction in the carbon intensity of energy supply. This decarbonization of supply is prominent in energy and climate discourse, and has been evident in the electricity sector over the past decade. Measured as pounds of CO2 emitted per kWh generated, the emission rate for all electricity generated in the U.S. last year was 16 percent less than the rate in 2005. For that we can thank increased generation from lower-carbon natural gas and zero-carbon wind. (Solar electric generation, though growing very fast, started from a tiny base and wasn’t a notable factor in the decarbonization to date.) Energy efficiency has helped as well by reducing the need to fire up high-carbon coal plants.

A carbon emissions tax, which by its nature favors wind and solar over gas, and gas over coal, will help sustain and accelerate this encouraging supply-side trend. Indeed, the price-sensitivities built into CTC’s spreadsheet model imply that energy supply decarbonization will account for an estimated 53 percent of the overall projected CO2 reductions from any carbon tax. This means that reductions in emissions via demand, i.e., conservation and/or efficiency, that are Goldstein’s stock-in-trade need only accomplish a bit under half (47 percent) of the total task.

The relevant math, then, is this: Thanks to supply decarbonization, the U.S. can limit its reduction in energy usage to 59 percent and still achieve the 85 percent CO2 reduction target. While a roughly 60 percent reduction in energy consumption is still a tall order, it’s far less fantastical than 85 percent. Assuming energy price-elasticities average minus 0.5, that 60 percent reduction in usage could be effected with a “mere” 6-fold rise in energy prices. No 44-fold rise required. (See calculations at end of this post.)

The relevant math, then, is this: Thanks to supply decarbonization, the U.S. can limit its reduction in energy usage to 59 percent and still achieve the 85 percent CO2 reduction target. While a roughly 60 percent reduction in energy consumption is still a tall order, it’s far less fantastical than 85 percent. Assuming energy price-elasticities average minus 0.5, that 60 percent reduction in usage could be effected with a “mere” 6-fold rise in energy prices. No 44-fold rise required. (See calculations at end of this post.)

Argument #2: A Carbon Tax High Enough to Be Effective Would Distort the U.S. Economy

To his credit, Goldstein appears to have anticipated my rebuttal above. He posits a 5-fold increase in energy prices, slightly on the easy side of my 6-fold rise, which he then dismisses on three grounds. Each is problematic, however:

1. “Energy would be pushing a fourth of GDP” (vs. today’s share of ten percent or less), says Goldstein, and, thus, would gobble up too much economic activity. The idea of expensive energy colonizing the economy is definitely a concern in a last-gasp laissez-faire economy in which the costly energy arises through “extreme extraction” of oil from the Arctic, deep waters, and tar sands. But a carbon tax would have the opposite effect, obviating most energy exploration, extraction, conversion, transport and combustion, in accordance with the 60 percent decline in usage posited above. In short, a carbon tax will make our society and economy less energy- and fuel-intensive, not more (while the energy barons, with their wealth clipped, will wield less political power).

2. A 5- or 6-fold increase in energy prices “is not politically possible. Electricity at 50 cents a kilowatt hour?,” Goldstein asks rhetorically. “Gas at $12 a gallon?” Here, Goldstein presumes that a carbon tax would lead to those lofty prices overnight, rather than phasing in over decades. In the latter scenario, the impacts will be softened, yet the price signals guiding long-term investments will be loud and clear. The impacts will be tempered further as the improved efficiency of usage lets businesses and households heat, cool, light and move with fewer units of energy. (Ironically, it was Goldstein and his NRDC colleagues who coined the mantra that what matters is electricity bills and not rates. Note also that CTC is on record criticizing proposed carbon taxes that would start with abrupt energy price rises, on account of the likelihood of economic dislocation.)

3. The carbon tax required to boost energy prices 5- or 6-fold “would be potentially devastating to the poor,” Goldstein argues. Potentially yes, if the wealthy are allowed to siphon off the carbon tax revenues that could buffer U.S. households from the higher energy prices. But the carbon tax designs with the most adherents are those that either use the proceeds to reduce regressive job-killing payroll taxes or distribute them pro rata to households as “fee-and-dividends.” In fact, the need for a socially and economically just distribution of carbon tax revenues only underscores the urgency for environmental progressives to coalesce now behind carbon tax legislation that can safeguard the 90 percent rather than solidifying the advantages held by the top 10 or 1 percent.

Argument #3: Energy Demand is Price-Inelastic, So a Carbon Tax Won’t Affect It

Goldstein next revisits energy price-elasticity in an attempt to show that its actual value lies closer to a barely behavior-influencing (minus) 0.1 than the more robust (minus) 0.5 figure he granted earlier for argument’s sake. But curiously, he builds his case on a commodity that no end-user actually purchases: crude oil. Refineries consume crude, of course, but the businesses and households whose decisions determine aggregate demand consume petroleum products: The fuels whose price-elasticities need to be estimated empirically are gasoline, diesel fuel and jet fuel ― not crude oil.

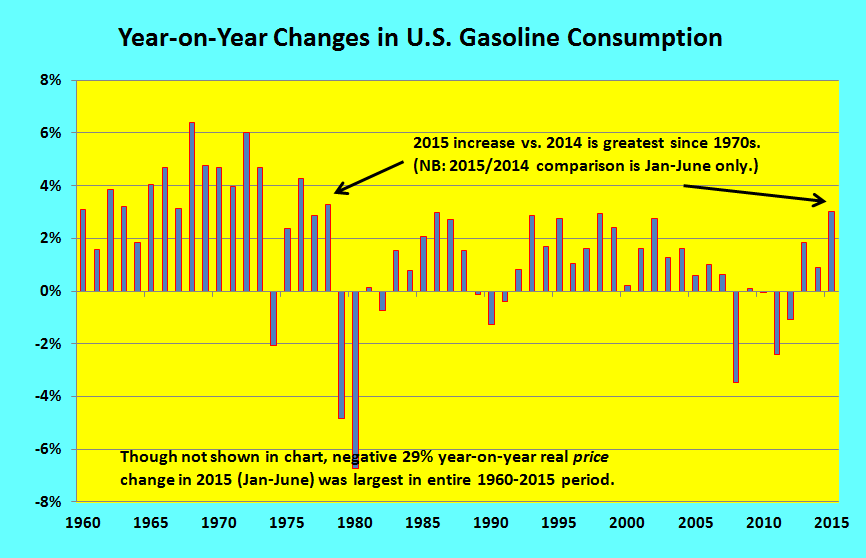

Over the years there’s been no dearth of claims by representatives of Big Green groups that changes in the price of gasoline elicit little change in usage. Most of these claims are either mere assertions or rest on cursory and selective glances at the data. Perhaps this year’s surge in gasoline sales will finally put that notion to rest: U.S. gasoline sales in the first half of 2015 were 3 percent above 2014 sales — the biggest year-on-year increase in gasoline demand since the late 1970s (subject to the caveat that the comparison covers only six months in each year). The driving force behind this surge isn’t economic activity, since GDP for the first half of 2015 grew only at a middling rate of 2.8 percent; the reason is free-falling pump prices. (NB: The original version of this post had first-half 2015 sales growth at 3.3% over 2014; that figure has been changed to 3.0%, with revised data. The assertion that this is the biggest increase since the late seventies remains valid.)

In any event, the way to estimate gasoline’s (or other fuels’) price-elasticity is with multivariate regression analysis. Here’s a summary of the estimation I performed for gasoline for CTC’s carbon-tax spreadsheet:

In any event, the way to estimate gasoline’s (or other fuels’) price-elasticity is with multivariate regression analysis. Here’s a summary of the estimation I performed for gasoline for CTC’s carbon-tax spreadsheet:

Using an approach suggested by retired energy economist Vince Taylor, who earned his PhD at M.I.T. from Nobel laureate Robert Solow in the 1960s, and whose insights animated my 1981 magnum opus on nuclear power cost escalation, I “regressed” the annual percentage changes in U.S. gasoline consumption from 1960 through 2014 on three independent variables: (i) the same year’s percentage change in economic activity (GDP); (ii) the same year’s percentage change in the average real retail price of gasoline; and (iii) the average percentage change in that price over the 10 years prior to the current year. The third variable was intended to reflect lags inherent in Americans’ responses to changing gasoline prices, insofar as automobile purchases and location choices that affect usage tend to change over years rather than weeks or months. The parameters may be referred to as income-elasticity, immediate price-elasticity, and lagged price-elasticity, respectively.

Two “models” best fitted the data, both statistically and conceptually. (All variables were statistically significant.)

- One model yielded an income-elasticity of 0.47; an immediate price-elasticity of (minus) 0.12; and a lagged price-elasticity of (minus) 0.21. The sum of the immediate and lagged price-elasticities was (minus) 0.34.

- The other model added a “dummy” variable to adjust for an arguably atypical six-year period covering 2002-2007. This variable was premised on the unusually high discounts/rebates offered for SUV’s during that period, as well as America’s post-9/11 paranoia and Iraq War-inspired triumphalism that may have contributed further to higher purchases and use of SUV’s. (SUV’s average more gas per mile than sedans, of course.) The regression results were, respectively: +0.46, -0.13, -0.24, and +1.4%, indicating an income-elasticity of 0.46; an immediate price-elasticity of (minus) 0.13; and a lagged price-elasticity of (minus) 0.24. The sum of the immediate and lagged price-elasticities was (minus) 0.37. (We ignored the dummy variable as transitory; its inclusion in the model was to filter out influences that could distort the elasticity estimates. May 2016 addendum: we repeated both regressions with 2015 data added. The only change was a slightly reduced income-elasticity in the three-variable model in the prior bullet, to 0.46, from 0.47.)

- From the two sets of regressions, we rough-averaged the respective price-elasticity sums of (minus) 0.34 and (minus) 0.37. The result, a figure of (minus) 0.35, is the price-elasticity we use in our spreadsheet model to estimate the long-term responsiveness of gasoline demand to a carbon tax.

In the CTC carbon-tax model we specify higher price-elasticities for other energy-use sectors: (minus) 0.5 for diesel fuel, (minus) 0.6 for jet fuel, and (minus) 0.7 for electricity. We premise them on businesses’ greater capacity to respond to higher energy prices than drivers’, and on our gleanings from the extensive literature of price-elasticity.

The takeaway? The price-elasticities of U.S. energy usage, while not necessarily high (all are below one), are not only much greater than what Goldstein suggests; they’re large enough to establish beyond any doubt that taxing carbon emission will indeed reduce energy usage, rather than merely punishing consumers into paying more for the same amount of energy.

Argument #4: The Best Path to Carbon Reductions is Prescriptive Energy Policies

So what is the Goldstein-NRDC solution, if not carbon emissions pricing? Here’s Goldstein’s prescription:

This [pessimistic] analysis does not apply to actually implemented or proposed cap-and-trade plans, such as the one adopted by California pursuant to AB32 or the one proposed in the Waxman-Markey bill, both of which rely primarily on non-price energy policies. The overwhelming bulk of emissions savings come from (1) improved building and equipment efficiency standards, (2) integrated land use and transportation system planning that meets goals for travel reduction, (3) emissions standards on fuels and vehicles, (4) requirements for utilities to purchase and integrate renewable energy sources, (5) regulatory reforms that encourage utilities to rely primarily on energy efficiency, and (6) a host of other policies that are independent of energy prices. Numerals added; otherwise quoted verbatim.

That’s NRDC’s credo in a nutshell, and much of it is admirable — particularly #1, which I touted at the start of this post; also #4, which helped jump-start the U.S. wind-power industry (though perhaps no more than did the federal Production Tax Credit for wind electricity), and #5, an effort in which I participated peripherally as a utility reform advocate at the dawn of the “demand-side management” era several decades ago.

On the other hand, it can be argued that the vaunted CAFE standards (#3) were only able to be legislated in the mid-1970s and ramped up several times since then because of rising gasoline prices — somewhat mooting the standards and demonstrating the power of prices that Goldstein largely discounts. Moreover, Goldstein’s #2 is stunningly squishy (“planning that meets goals for travel reduction”); yes, Goldstein had to shoehorn his description but the fact is that NRDC’s standards-and-regulations approach, which has proven so potent in making appliances more efficient, is powerless to rein in the use of vehicles.

The Crux

And therein lies the fundamental difference between Goldstein’s (NRDC) and my (CTC) respective approaches. Miles-per-gallon rules reduce carbon emissions per vehicle-mile driven, but they do nothing to affect the other half of the formula that equally determines emissions: the number of vehicle-miles driven.

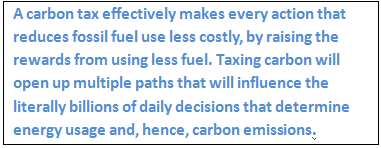

In contrast, a carbon tax effectively makes every action that reduces fossil fuel use less costly, by raising the rewards from using less fuel. Taxing carbon will open up multiple paths that will influence the literally billions of daily decisions that determine energy usage and, hence, carbon emissions.

In driving, a carbon tax will affect whether and how far and often to drive . . . which car to take on a family trip . . . how high an mpg rating to demand in the next lease or purchase . . . and, at the societal level, whether public transit investments “pencil out” and might be prioritized over wider highways, and whether hyper-efficient car designs pencil out in corporate boardrooms and venture-capital spreadsheets.

The same goes for other energy-use sectors. Costlier diesel fuel will not only stiffen legislators’ and regulators’ spines in promulgating truck mpg standards; they’ll incentivize local and regional provision over far-flung shipping of food, raw materials and consumer goods, thus cutting down on freight-miles and resultant emissions. Rising electric rates — at least during the decades until carbon fuels are eliminated — will not only strengthen NRDC’s and ACEEE’s case for ever more-efficient appliances; their price pressures will help restrain the size and number of appliances sold and also motivate consumers to use them more efficiently.

Costlier electricity and natural gas will likewise discourage developers from building, and families from insisting upon, gargantuan homes whose outsize volumes must be heated and cooled. Not to mention that a carbon tax provides an antidote to the oft-postulated “rebound effect” by which increased energy efficiency, by reducing the implicit price of energy services, can engender greater energy usage and inadvertently cancel some of the intended savings from those efficiencies. A carbon tax acts as a direct brake on that implicit price reduction and, thus, on the rebound effect.

The point is clear: No other policy can match a carbon tax’s reach, or its simplicity. As we wrote last year in comments we submitted to the Senate Finance Committee concerning energy subsidies and pricing:

The U.S. energy system is so diverse, our economic system so decentralized, and our species so varied and innovating that no subsidies regime, no matter how enlightened, and no system of rules and regulations, no matter how well-intentioned, can elicit the billions of carbon-reducing decisions and behaviors that a swift full-scale transition from carbon fuels requires. At the same time, nearly all of those decisions and behaviors share a common, crucial element: they are affected, and even shaped, by the relative prices of available or emerging energy sources, systems and choices. Yet those decisions cannot bend fully toward decarbonizing our economic system until the underlying prices reflect more of the climate damage that carbon fuels impose on our environment and society.

Carbon Taxing Going Forward

Two carbon tax bills now before Congress — submitted by Reps. Jim McDermott (D-WA) and John Larson (D-CT) — ramp up the tax level steadily and predictably to reach triple digits (i.e., $100 per ton of CO2) a decade on. Our modeling suggests that either bill, by the end of its tenth year, will have reduced total U.S. carbon emissions from fossil fuel burning by more than 30 percent, vis-à-vis 2005 emissions — with the reductions rising as the tax level continues ramping up. As noted, a little more than half of the reductions will come about by sustaining and accelerating the ongoing decarbonization of the U.S. fuel mix, not just in electricity but by motivating increased electrification of sectors like driving that are now dominated by hydrocarbon fuels. The remainder will result from energy efficiency and conservation, i.e., reduced usage per unit of economic activity.

Such a carbon tax has myriad other advantages, including the ease with which it can be replicated globally, that no other approach can match. One unsung advantage is that taxing carbon harmonizes with other measures for reducing energy consumption and carbon emissions. My or other individuals’ energy-savings don’t undermine the tax’s effect on other economic actors ― whereas under cap-and-trade, autonomous energy-saving actions lower the price of the emission permits and thus attenuate the price signal. Likewise, a carbon tax reinforces the economic effectiveness of the appliance and vehicle and building efficiency standards so ably championed by David Goldstein and NRDC, just as those standards play an essential role in overcoming the market failures that are hard to counteract with price signals alone.

It’s 26 years and counting since my first carbon tax op-ed, and almost 9 years since I co-founded the Carbon Tax Center. We at CTC have long since abandoned the hope that NRDC or the other big green giant, the Environmental Defense Fund, would lead the charge for a U.S. carbon tax. We’re okay with that, but we ask our environmental colleagues to refrain from devising and attacking straw-man versions of carbon taxes.

We’ve never said that “carbon emissions fees alone can . . . solve the climate problem.” Rather, we believe that the climate problem can’t be solved without them.

Calculations for 9th paragraph in post: If decarbonization of supply is to account for 53% of the CO2 reduction, and reduction in usage for the other 47%, then K, the percentage change in usage needed to reduce CO2 by 85%, is calculated by the equation: K x K x .47/.53 = 0.15. That is solved by K = 0.41, which equates to a 59% reduction in usage. To effect such a reduction, assuming price-elasticity of -0.5, the factor increase in energy prices, M, is given by the equation: M^(-0.5) = 0.41. The solution is M = 5.95, denoting a 6-fold price rise.