We kick off this page with a Carbon Tax Center tweet of a June 2022 New York Times Business story, Fossil-Fuel Shares Lead the Stock Market. How Awkward.

Unstated but implied in this devastating @nytimesbusiness story: campaigns to divest institutions (banks, universities, foundations, pension funds) from FF's use up activist time & energy, for nada. Better to fight SUVs, sprawl, NIMBYs, anti-carbon-taxers. https://t.co/Tg1xlGQH1c

— Carbon Tax Center (@carbontaxcenter) June 5, 2022

Awkward indeed. The soaring prices of oil company stocks in the first half of 2022 should lay to rest, once and for all, hopes that the decade-long campaign to pressure fiduciary institutions to purge their holdings of fossil-fuel companies will depress these companies’ shares and lead them away from investing in coal, oil and gas supplies — either out of principle or because of poor returns.

Since climate activist Bill McKibben launched the divestment movement in a 2012 Rolling Stone article, Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math, campaigns have targeted universities, municipalities, pension funds and foundations. Some have responded. By late 2021, institutions pledging to divest their fossil-fuel holdings included private universities like Harvard (my alma mater) and Georgetown; state universities like U-Michigan and U-California; pension funds serving New York City, New York State and Quebec; Ireland’s sovereign wealth fund; large Protestant and Catholic institutions; and the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations, the former built on wealth derived from gasoline-powered automobiles, the latter directly from petroleum.

That list is excerpted from This Movement Is Taking Money Away From Fossil Fuels, and It’s Working, an October 2021 New York Times op-ed by Bill McKibben, the activist writer who started the climate advocacy organization 350.org and helped spark the divestment movement.

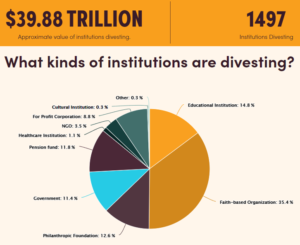

“Endowments, portfolios and pension funds worth just shy of $40 trillion have now committed to full or partial abstinence from coal, gas and oil stocks,” McKibben wrote in the Times. “For comparison’s sake, that’s larger than the gross domestic product of the United States and China combined.”

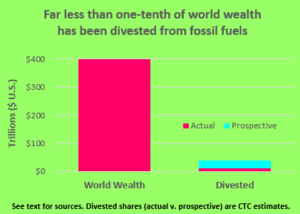

From divestmentdatabase.org, accessed Nov 1, 2021. The active form of the verb “are divesting” makes clear that much of the divestment is only promised.

Even with McKibben’s caveat that much of the $40 trillion is only partial and/or committed, the comparison is inapt. The already or to-be divested funds represent wealth, whereas American and Chinese GDP are annually recurring flows. The appropriate comparison, of course, would be to world wealth, a figure in excess of $400 trillion, according to Boston Consulting Group, which in 2020 estimated the world’s financial assets at $250 trillion in 2020. Real property assets probably amounted to an additional $150 trillion or more.

To be sure, these metrics of wealth ignore the immense value of natural ecosystems that underpin economic activity, which means they also overlook nature’s degradation from humankind’s rampant consumption. Nevertheless, McKibben’s $40 trillion divestment estimate and the Boston Group’s $400 trillion wealth figure come from the same methodologies, making them fit for comparison. The optimistic takeaway, then, is that a tenth of world wealth is or may soon be divested from fossil fuels.

What has the climate gained from this purported divestment? Not much. As we wrote in 2015,

Divestment by socially responsible investors, universities and even governments won’t starve capital flows to fossil fuel corporations anytime soon. That’s because in a global market, every share of stock we activists dutifully unload will be snatched up in milliseconds by some trader who can bank on humanity’s continued dependence on fossil fuels to continue generating profits.

Most of the announced divestment is prospective. For example, the commitment by France’s La Banque Postale is due in 2030.

In other words, no matter how far divestment campaigns manage to reach into J.P. Morgan Chase or Citicorp, a world insistent on using fossil fuels will still be able to draw on a vast array of wealth holders to finance their resupply. McKibben admitted as much in his op-ed, noting that “private equity funds have invested at least $1.1 trillion into the energy sector since 2010, overwhelmingly in fossil fuels.” (He graciously linked to an earlier Oct. 2021 Times story, Private Equity Funds, Sensing Profit in Tumult, Are Propping Up Oil.)

In a further burst of candor, McKibben pretty much conceded that rather than cutting off Big Carbon’s access to capital, the real objectives of the decade-long divestment campaign have been to build the climate movement and also erode the social and political standing of the fossil fuel industry:

Since most people don’t have oil wells or coal mines in their backyards, divestment is a way to let a lot of people in on the climate fight, because they have a link to a pension fund, mutual fund, endowment or other pot of money. When we began the divestment campaign, our immediate goal was, as we put it, to “take away the social license” of Big Oil.

CTC has always granted divestment’s “movement-building” feature. And there’s something to be said for eroding the social standing of fossil-fuel extractors and purveyors. But that project has a painfully long time horizon. And what happens when all those bright-eyed divestment activists discover that their success in moving their college or municipal pension fund out of fossil fuels hasn’t translated into any apparent change in the material world of energy production and consumption? And when they awaken to the knowledge that even “cancelled” Exxon executives and pipeline welders aren’t pariahs in the oil fields and board rooms.

So long as we’re using fossil fuels to get around and to keep our homes warm and toasty, there’ll be an oil sector to get it done. Stripped of its movement-building, divestment is a fruitless diversion from the hard work of actually destroying demand for fossil fuels.