Carbon Dividends (“Green Checks”)

Another approach for handling carbon-tax revenues, one that is clearly income-progressive and appealingly straightforward, is to return the revenues equally to all U.S. residents. This so-called “dividend” would be a national version of the Alaska Permanent Fund, which since the 1970s has annually sent all state residents identical checks drawn from earnings on investments made with the state’s North Slope oil royalties. (For a federal carbon tax, the “dividend” checks should be provided quarterly or monthly to keep households ahead of the budget treadmill.)

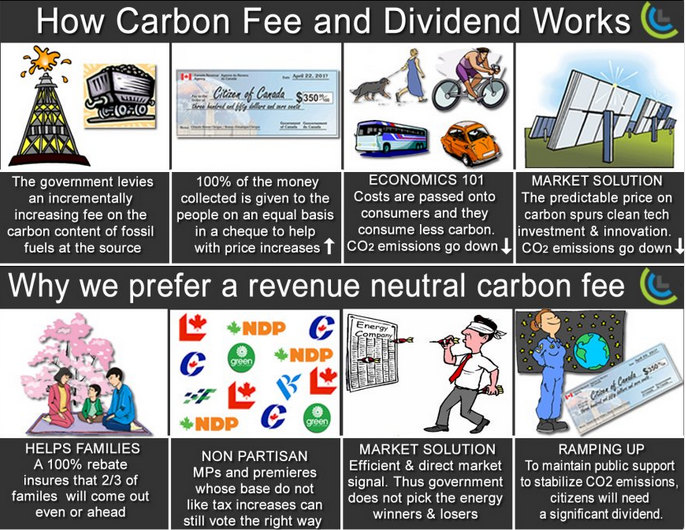

The dividend approach was so attractive and elegant that the nation’s (and perhaps the world’s) most energetic and active advocacy organization for carbon taxes has organized around it. That’s the Citizens’ Climate Lobby, which calls its approach carbon fee-and-dividend.

Fee-and-dividend explained, Canadian style. Hat tip to @scottsantens.

Nevertheless, it seems fair to say (and important to acknowledge) that by 2018, the second year of the Trump administration, fee-and-dividend has run out of political room. Not a single “sitting” (i.e., still in office) Republican member of Congress has publicly endorsed fee-and-dividend, even as a concept, let alone an actual bill. Yet the premise of fee-and-dividend has always been bipartisanship, since Democrats, with their preference for activist government, would accept a revenue-neutral carbon tax such as fee-and-dividend only if it delivered Republican votes.

For a decade, we wrote glowingly about fee and dividend — most recently in 2017 articles in The Nation and the Washington Spectator. We also praised the Climate Leadership Council’s “carbon dividend” proposal and advocacy in those two pieces and in numerous blogs (here, here, and here, inter alia). But as we wrote in June 2018, we believe that the time for carbon dividend proposals has probably passed. We wrote:

The [political] center to which Baker-Shultz (CLC) and fee-and-dividend (CCL) were designed to appeal barely exists. It’s not just that no sitting Republican has endorsed Baker-Shultz or indeed fee-and-dividend in any form. It’s also that the Democratic majority that will be needed to pass a carbon tax bill appears unlikely to rally around a revenue-neutral carbon tax, whether it’s organized as fee-and-dividend or some form of tax swap.

Economic Progressivity of Fee-and-Dividend

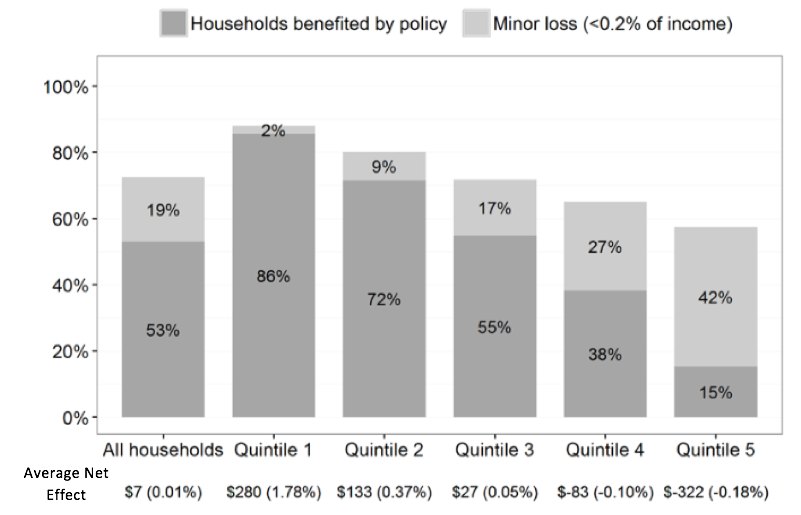

In 2016 CCL released a detailed paper examining how a carbon fee-and-dividend would impact U.S. households. The study took into account geographic variations in electricity sources and gasoline use and drew on a database of carbon intensity of expenditures for 5.8 million households to analyze the net effect of returning revenue to households on a modified per capita basis. Here are the major results:

- 53% of households (and 58% of individuals) would receive more in dividend payments than they would spend due to higher fossil fuel prices.

- Another 19% of households would incur only a slight loss, defined as a net loss no larger than one-fifth of one percent of pre-tax income.

- Nearly 90% of households below the poverty line would benefit an average of $311, an increase of roughly 2.8% of pre-tax income.

- In contrast, the net loss for the top quintile of households would average $-322 or only -0.18% of pre-tax income.

Notably, these findings support a dividend plan’s ability to transform a carbon tax into a progressive policy that neutralizes the burden that lower-income households would otherwise face, directly and indirectly, due to higher fuel prices. CTC advocates a progressive distributional outcome for both pragmatic and ethical reasons: pragmatically, because a carbon tax will require broad, sustained, public and political support; and ethically, because it’s not tenable to solve the climate crisis on the backs of those who can least afford it.

A Caveat — CBO’s “haircut”

The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office routinely “scores” members’ bills for their prospective impact on tax revenues. To streamline its analyses, CBO long ago settled the so-called “CBO haircut” by which it assumes that one-quarter of indirectly raised revenues would need to be allocated from the tax proceeds in question in order to make up for reduced tax revenues collected from conventional sources such as personal or corporate income taxes. But modeling of carbon tax proposals consistently finds that when revenue is strategically returned by reducing other taxes that tend to slow down economic activity, the net negative impacts are much lower than CBO’s 25% assumption and in some cases may be eliminated altogether. While returning revenue as “dividends” (which economists call “lump-sum rebates”) offers less potential to reduce economic drag than tax shifts, CBO’s assumption still seems like an over-estimate.

In any event, rigid application of the 25% CBO haircut could, on paper at least — and, likely, in Congressional deliberations — limit the carbon tax revenue perceived to be available for “dividends” to 75%. Yet even with this reduced fraction of revenue, returning carbon tax revenue via a direct dividend represents a simple and income-progressive means to make carbon taxes distributionally fair; though with the haircut, the share of households reaping a net benefit via an equal 75% dividend would be lower than the 58% of individuals mentioned above.

Related CTC blog posts:

- The Carbon Tax Revenue Menu (6/10/11).

- Should Carbon Pricing Advocates Support the Cap-and-Dividend Bill? (12/2/10).

- Scientist James Hansen Proposes “People’s Climate Stewardship Act”: A Simple Carbon Fee with Revenue Returned to Americans (4/25/10).

- Progressive Democrats Say: “Cut Out Wall Street — Price Carbon Directly and Recycle Revenue to Households.” (10/20/09).

- Back to Plan A: The Revenue-Neutral Carbon Tax (7/6/09).

Related news reports and opinion pieces:

- Alaska’s Permanent Dividend Fund — A policy ripe for export (Bangor Daily News, 6/20/2011).

- James Hansen Rails Against Cap-and-Trade in Open Letter, Advocates Fee-and-Dividend to Reduce Carbon Emissions (The Guardian, 1/12/2010).

- Cap and Fade (James Hansen, NYT op-ed, 12/6/2009).

- How CBO budget scoring devalues efficiency (Dave Roberts, Grist 10/15/2009).