A striking — and troubling — shift of late in the climate-policy landscape is the pronounced turn against carbon pricing by the environmental- and climate-justice movement — the community of individuals and organizations dedicated to overturning deeply entrenched inequities of disproportionate pollution burdens borne by African-Americans, Latinos, Asians and Pacific Islanders and Native Americans in the United States.

Most in that movement now appear to disdain carbon pricing as a climate policy tool, whether as a straight-up carbon tax or a permit-based cap-and-trade system. This shift is a blow to carbon tax prospects, not least because the broader progressive community increasingly is taking its lead from Black, Brown and Indigenous people who traditionally were excluded from leadership in environmental issues. Growing antipathy by EJ/CJ campaigners is one of the reasons that progressives’ interest in carbon pricing has cooled in recent years. (See in-depth discussion on our complementary page, Progressives and Carbon Pricing.)

This page begins by inquiring into the sources of that antipathy. It then recapitulates two 2020 Carbon Tax Center posts reporting new research crediting carbon pricing for reducing disproportionate dumping of pollutants on disadvantaged communities in California. Environmental Justice, Borne Aloft by Carbon Pricing, was posted in Sept. 2020. A follow-on, Dogmatism on Carbon Pricing Mustn’t Derail Climate Progress, was published in Dec. 2020.

We then summarize another 2020 study that found that the Clean Air Act has sharply reduced environmental inequality between racial groups across the United States, even though its provisions and enforcement did not explicitly target communities of color.

This new research, while heartening, does not yet appear to have prompted reconsideration of carbon pricing or other “universal” environmental and climate policies by environmental justice advocates.

The scene in San Francisco on Sept 10, 2018 as activists with the Climate Justice Alliance demonstrated outside California Gov. Jerry Brown’s Climate Action Summit.

Wellsprings of EJ antipathy to carbon pricing

A decade or so ago, at the start of the 2010s, many EJ/CJ campaigners opposed carbon cap-and-trade programs but were agnostic about carbon taxes. By the end of that decade, most in the movement were aligning against carbon taxing as well. Some did so with increasing stridency, branding any carbon pricing as harmful, even “colonialist” (see photo).

The turn against carbon pricing by many environmental and climate advocates of color has multiple causes and antecedents, including:

- Belief that carbon pricing commodifies both nature and humans’ right to a safe environment and climate.

- Conflation of carbon pricing with predatory capitalism that, over centuries, brought prosperity to whites by stealing the land of Indigenous people and the labor of people of African descent.

- Fear that carbon pricing necessarily entails “offsets” that let polluters buy their way out of reducing local pollution.

- Conviction borne from an early and easily gamed pollution-pricing program — California’s RECLAIM cap-and-trade system to cut nitrogen oxides — that carbon pricing perpetuates pollution “hot spots” in disadvantaged communities.

- A preference for addressing the climate crisis by attacking entrenched power imbalances that skew against communities of color rather than through so-called “race-blind” policies that, at least on their face, appear to ratify those imbalances.

- The mistaken belief that California’s carbon cap-and-trade program is exacerbating long-standing pollution-exposure disparities between disadvantaged communities and whiter, affluent populations.

Further below, we unpack the sixth and final bullet — the deeply held but erroneous conviction that California’s permit-based carbon-pricing system is worsening the disproportionate pollution burden borne by low-income communities of color. It should be said, however, that it is the the cumulative power of the five other conditions that has given this misplaced conviction such great salience in the environmental justice movement — initially in California and now nationwide.

2015-2020: EJ criticism mounts against carbon pricing

We first wrote about environmental justice and carbon pricing in 2016, prompted by a column in Yale 360 by 350.org co-founder and prolific climate activist Bill McKibben. In Why We Need a Carbon Tax, And Why It Won’t Be Enough, McKibben wrote:

Carbon rebates also come with one obvious moral and intellectual flaw: most of the damage from both climate change and air pollution has fallen on poor people, people of color, and Native nations, both in our country and around our world. They need to be treated fairly in any rebate plan. And any such rebates shouldn’t overlook the estimated nearly 12 million undocumented Americans who contribute to the economy — and cause far less than their proportional share of emissions. Environmental justice would mean a truly “fair” system compensated them for that history; it would also require policies to make sure that carbon pricing doesn’t perpetuate toxic “hot spots” in poor communities as companies look for least-cost ways to deal with the new reality. Furthermore, environmental justice demands that carbon prices don’t create a windfall on other of forms of ecological or toxic energy production, such as mass incineration or mega-hydro dams. (emphasis added)

McKibben’s first charge to carbon-pricing proponents, that the necessarily higher prices of fossil fuels not disadvantage poor people and people of color, was one that CTC and other carbon-tax advocates had addressed for years (our Ensuring Equity page, has details). Our response to McKibben, published as Carbon Tax Can Be a Remedy for Toxic Hot Spots, summarized our antidotes to economic regressivity. We then turned to hot spots.

“From time to time,” we noted, “concern is voiced that polluting companies will respond to carbon taxes by curbing carbon pollution elsewhere rather than in frontline communities like blighted urban neighborhoods, Appalachian hollows, or Native peoples’ lands.” To head off those possibilities, we urged “members of frontline communities to assume leadership positions in the carbon tax effort.”

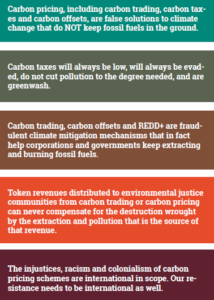

From “Carbon Pricing: A Critical Perspective for Community Resistance.” Link to that report is in text.

Hopes for that partnership soon dwindled, with publication by the Indigenous Environmental Network and the Climate Justice Alliance of “Carbon Pricing: A Critical Perspective for Community Resistance” in November 2017. The manifesto nature of this 60-page report was telegraphed by its boldface message on page 3: “This publication will help communities and organizations articulate crucial points to resist carbon pricing and carbon change.”

The paradigm of resistance to carbon pricing suffused the report’s five “main takeaways” (shown at left). Carbon pricing was deemed a “false solution” that “does not keep fossil fuels in the ground.” Rather than a climate-damage antidote or preventive, carbon pricing was, at best, merely “remedial.” Better to “fight fossil fuel subsidies” and “build power,” the report stated, than succumb to polluters’ carbon-pricing “greenwash.”

Then and now, CTC has no argument with the call for frontline and disadvantaged communities to build power. But build power toward what? If ending fossil fuel subsidies is part of the solution, it needs to be said that “fossil fuel subsidies” as commonly defined — taxpayer-funded payouts or tax breaks such as the oil-depletion allowance — are dwarfed in the United States and most other industrial countries by the climate and health damages from extracting and burning fossil fuels. Which means that the real fossil fuel subsidy, as we point out on our Subsidies Reform page, is the absence of carbon pricing.

Anti-pricing rhetoric also suffuses the April 2021 edition of climatefalsesolution.org’s “Hoodwinked in the Hothouse” guidebook for “Resist[ing] False Solutions to Climate Change.”

The following September (2018) saw the “Solidarity to Solutions” action in San Francisco depicted in the earlier photograph. We reached out to one of the participants, just as we had, a year earlier, to one of the prime movers of the IEN/CJA manifesto. In both cases, our entreaties for dialogue were rebuffed. Tellingly, one party informed us, “We do not have the capacity for engaging deeply with individuals that are not rooted in an organization with accountability to a base of people — there may be other organizations who have that capacity, but we do not.”

An incomplete analysis of cap-and-trade hardens EJ opposition in California

Concurrently, in California, a research project examining the incidence of pollution from California’s carbon cap-and-trade law, AB 32, was adding to environmental justice campaigners’ antipathy to carbon pricing.

That project, by a team of academics led by Prof. Lara Cushing, published its findings in a 2018 paper in the journal PLOS Medicine Carbon trading, co-pollutants, and environmental equity: Evidence from California’s cap-and-trade program (2011–2015). However, the team’s preliminary findings had begun circulating as early as 2016, helping turn opinion against the cap-and-trade program in the EJ community and its allies.

The Cushing team concluded that, following implementation of the cap-and-trade program, a majority (52 percent) of California “regulated facilities” — the state’s roughly 300 largest “stationary” sources of carbon dioxide emissions — increased rather than curbed their emissions of greenhouse gases. Moreover, the increases in carbon co-pollutants such as particular matter and nitrogen oxides were disproportionately concentrated in communities with “higher proportions of people of color and poor, less educated, and linguistically isolated residents,” according to the PLOS paper.

These conclusions left an indelible imprint on discourse about carbon pricing and environmental justice. Yet they rested on shaky ground. The Cushing analysis had no control group, leading it to mistake the cap-and-trade program as the cause of rising emissions in disadvantaged communities when emissions actually increased across all of California as economic activity rebounded from the 2008-09 recession. It also assumed that smokestack emissions deposited within a few miles, ignoring wind patterns and tall smokestacks that sometimes dispersed pollutants far from frontline communities. Last, the analysis flattened the data into binary, “up or down” results, which inadvertently suppressed the tendency of bigger polluters to cut back the most as the cap-and-trade incentives kicked in.

2020: A pair of UCSB economists improve on, and reverse, that analysis

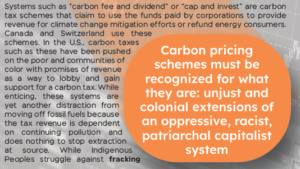

Figure from Hernandez-Cortes & Meng NBER paper showing simulated particle trajectories from a polluting facility in Los Angeles in 2016.

After reading elements of the work by Cushing et al., two economists at U-C Santa Barbara — PhD candidate Danae Hernandez-Cortes and Associate Prof. Kyle C. Meng — embarked on an ambitious research methodology that would improve on the Cushing work in three respects.

First, Hernandez-Cortes and Meng established a control group of 440 lesser California emitters that were not regulated by the cap-and-trade program; this “difference-in-difference research design” weeded out macroeconomic and other factors to discern the cap-and-trade program’s specific effects on emissions from the 306 larger, “covered” facilities.

Second, Hernandez-Cortes and Meng deployed an atmospheric transport model to track where the carbon co-pollutants actually deposit after they have been emitted.

Third, rather than assigning equal weight to the 300-plus facilities, the UCSB economists based their calculations on each facility’s emission quantity.

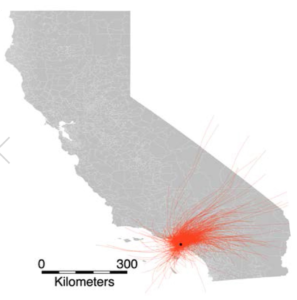

Hernandez-Cortes and Meng wrote up their work in a paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research, Do Environmental Market Cause Environmental Injustice? Evidence from California’s Carbon Market, first posted in May 2020 and revised in Feb. 2021. We’ve summarized their key findings in the table below.

The yellow columns display ground-level concentrations of particulate and gaseous carbon co-pollutants from California’s 306 largest carbon emitters in 2008. Perhaps even more striking than the “deltas” (numerical differences) between pollution concentrations in environmental justice vs. other communities are the ratios: pollution levels in the EJ communities in 2008 were three to four times as high as in other areas.

All data are from Hernandez-Cortes & Meng NBER working paper cited in text, except that CTC calculated Ratio column from first two columns. Those columns are from NBER paper Table S3 and indicate exposure levels due to cap-and-trade regulated facilities estimated across 722 (EJ) and 990 (Other) zip codes. Remaining figures were calculated from pre- and post-cap/trade slopes shown in NBER paper Table 1. Differences in last column from calculations with prior two columns are due to rounding.

It’s apparent from the green column that by 2012 each pollutant’s “EJ gap” — the excess pollution deposited on disadvantaged communities relative to other California locales — had worsened even from its shocking 2008 base. Thereafter, however, coinciding with the onset of the cap-and-trade program, the gap narrowed significantly, as shown in the final two columns.

Consider the Hernandez-Cortes – Meng findings in the third row of the table for PM2.5. That’s the fine particulate matter that lodges deep in the lungs and is implicated in illness and death from heart and lung diseases and strokes and is considered the most deadly air pollutant associated with industrial processes that emit climate-damaging carbon dioxide. Beginning in 2013, the EJ gap for fine particulates contracted, falling to 2.7 µg/m3 in 2017 (the last year for which pollution data was available). That was 30 percent less than the 2012 gap of 3.8, and less than the baseline figure of 3.0 µg/m3 as well.

The state’s cap-and-trade program had a similarly beneficial impact on oxides of nitrogen, or NOx, which is the key constituent (along with volatile organic compounds) of the photochemical smog that since the late 1950s has infamously blanketed skies and seared eyes and lungs across much of California, with disadvantaged communities bearing more of the impact. As shown in the table’s top row, from 2012 to 2017 the EJ gap for NOx shrank to 4.8 µg/m3, a level 21 percent below the 2012 figure. Similarly, the environmental justice gap shrank during the same five years by 24 percent for sulfur oxides and 30 percent for larger particulate matter, known as PM10.

EJ antipathy to carbon pricing strikes down the top candidate to head the EPA

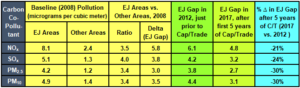

From Dec. 2, 2020 letter opposing prospective nomination of CARB’s Mary Nichols to head USEPA. Link in text goes to full letter with list of signatories.

Neither the Hernandez-Cortes – Meng paper, which was posted in May 2020, nor our write-up of it in September drew much commentary. Neither piece broke into the mainstream press or even climate-journalism sites such as Inside Climate News or ClimateWire. The Hernandez-Cortes – Meng paper received two mentions in the green press, in October and November (our Dec. 2020 “Dogmatism” post has details); both were cursory and largely dismissive, owing either to the writers’ inexperience or their reticence to question environmental justice dogma.

That reticence would soon prove consequential. On Dec. 2, less than a month after Joe Biden’s victory over Donald Trump, 70 environmental justice and allied groups sent a strongly worded letter to the Biden-Harris transition team opposing the prospective nomination of Mary Nichols, long-time environmental attorney and regulator and chair of the California Air Resources Board, to head the US Environmental Protection Administration.

A principal charge in the letter, and the one singled out by the New York Times and in other media accounts, was the claim, based on the Cushing analysis, that the carbon cap-and-trade program overseen and administered by Nichols and CARB “perpetrated environmental racism [by] increas[ing] pollution hotspots for communities of color in California.”

A NY Times editorial called EJ criticisms of California’s cap-and-trade program “largely specious,” but only when the Nichols nomination was safely in the rear-view mirror.

Though the claim lacked merit — Hernandez-Cortes and Meng had reached the opposite conclusion in their work, after correcting critical weak spots in the Cushing analysis — it stirred up opposition that the new administration could not attempt to counter without incurring significant political costs, as the New York Times noted in an editorial, excerpted at left, that appeared on Dec. 28 — after selection of North Carolina environmental quality secretary Michael Regan to be EPA Administrator.

(The Wall Street Journal waited an additional three months before noting in a March 24, 2021 column that “A coalition of environmental groups [had] accused [CARB head Mary Nichols] her of ‘pushing market-based approaches to the climate crisis at the expense of the health and well-being of California’s communities of color.’ But empirical evidence suggests otherwise. California’s carbon market actually narrowed disparities in exposure to particulates, nitrogen oxides and sulfur oxides, according to a study by economists Danae Hernandez-Cortes and Kyle Meng of the University of California, Santa Barbara.” Our Dec. 2020 post, Dogmatism on Carbon Pricing Mustn’t Derail Climate Progress, has a detailed discussion of how opposition to Nichols was stoked by misinterpretation of the California cap-and-trade program.)

A separate analysis finds that the Clean Air Act’s “universal” policy approach has benefited EJ communities nationwide

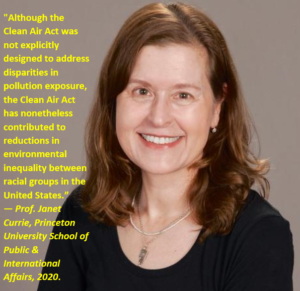

In Jan. 2020, Princeton Prof. Janet Currie and two other academics published a paper, What Caused Racial Disparities in Particulate Exposure to Fall? New Evidence from the Clean Air Act and Satellite-Based Measures of Air Quality.

The paper takes as its premise the statistically demonstrated (and heartening) finding, stated in the abstract, that “Racial differences in exposure to ambient air pollution have declined significantly in the United States over the past 20 years.”

Applying what it calls “newly available, spatially continuous high resolution measures of ambient particulate pollution,” the Currie paper makes three revelatory findings about declining levels of fine particulates (PM2.5) in the United States from 2000 to 2015:

-

- Areas with larger black populations experienced greater declines in PM2.5 exposure.

- The black-white gap in mean pollution exposure to PM2.5 has decreased from 1.5µg/m3 (micrograms per cubic meter) in 2000 to only 0.5µg/m3 in 2015 — a two-thirds reduction.

- Over 60 percent of this “convergence” (reduction) in the black-white pollution gap is attributable to regulatory measures related to and required by the Clean Air Act.

The Currie paper concludes:

These findings suggest that the Clean Air Act has likely played a significant role in reducing the black-white gaps in exposure to air pollution, because the legislation systematically targeted the dirtiest areas for cleanup, and African Americans were disproportionately likely to live in areas with dirty air. Hence, although the Clean Air Act was not explicitly designed to address disparities in pollution exposure, the Clean Air Act has nonetheless contributed to reductions in environmental inequality between racial groups in the United States. (emphasis added)

Though written as “universal” rather than targeted policy, the Clean Air Act has greatly reduced racial disparities in pollution impacts, according to a recent paper.

The bolded passage signifies the enduring value of the “universalist” approach to pollution reduction embodied in the Clean Air Act and other foundational environmental legislation, circa 1970. Rather than prioritize one set of communities over another, the Clean Air Act was designed to mitigate environmental pollution and its effects on everyone, everywhere. And if communities of color were the furthest from those standards (which of course they were, overwhelmingly, on average), then the mandated improvements in those communities would have to be disproportionately large.

That is, although “early” environmental legislation, which was driven and to a great extent written by the environmental movement of that era (the late 1960s and early 1970s), was not framed in terms of differential pollution impacts between rich and poor or Black and white, it nonetheless has had the effect of reducing those differentials.

The Currie paper won’t be the last word on pollution differentials. It doesn’t address the pollution gap between white or Black populations and Hispanic/Asian/Native populations. Rapidly rising Hispanic and Asian-American populations, both nationwide and in California, e.g., in the heavily polluted and largely Hispanic San Joaquin Valley, make this an urgent research priority.

Nevertheless, the Currie paper is valuable in its own right and for the light it casts on another universal policy: carbon pricing. Provided that carbon pricing programs aren’t saddled with “offsets” or other invitations to game the system, they almost certainly bend toward reducing both absolute pollution levels and race-based pollution gaps — a point argued at length in our late-2020 posts (Sept. 2020 and Dec. 2020) already discussed here.

Further confirmation of the shrinking clean-air gap between Black and white Americans

A Sept 2021 Atlantic article, Why Americans Die So Much, reports newer research reinforcing Currie’s finding of disproportionately positive benefits to Black and other non-white Americans from U.S. “universal” environmental policies. Author Clive Thompson summarizes a new National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, Inequality In Mortality Between Black And White Americans By Age, Place, And Cause, And In Comparison To Europe, 1990-2018, written by a team led by Northwestern University professor Hannes Schwandt. Amid the bad news of falling U.S. life expectancy, the NBER paper includes what Thompson calls “a surprising success story in U.S. longevity”: a near-halving of the Black-white life-expectancy gap from 1990 to 2018, prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Thompson writes:

In the three decades before COVID-19, average life spans for Black Americans surged, in rich and poor areas and across all ages. As a result, the Black-white life-expectancy gap decreased by almost half, from seven years to 3.6 years. [One reason was] reductions in air pollution. “Black Americans have been more likely than white Americans to live in more-polluted areas,” Schwandt said. But air pollution has declined more than 70 percent since the 1970s, according to the EPA, and most of that decline happened during the 30-year period of this mortality research.