The essence of carbon taxes is to make fossil fuels more expensive. That will motivate electricity providers to decarbonize their fuel mix and incentivize businesses and households to become more energy-efficient. However, it will also add financial stress, particularly for lower-income families and coal-dependent areas, unless some of the revenues are directed to those groups and places.

It bears repeating that carbon taxes, to be fully effective, must rise quickly and high — to the point that they will raise large sums of revenue. But generating new government dollars isn’t their primary purpose; indeed, distributing revenues from carbon taxes as “carbon dividends” or using them to cut onerous taxes like payroll taxes in revenue-neutral “tax shifts or swaps,” has been built into many carbon tax proposals.

Rather, the intent of robustly taxing carbon emissions is to cut those emissions by making burning fossil fuels convincingly costlier than conservation, efficiency and renewable energy. Rather than needing more tax revenue to cut CO2 emissions, we need to shift more of the total tax burden onto dirty energy, without harming low- and middle-income families.

Different effects of carbon taxes across the income range point toward carbon dividends

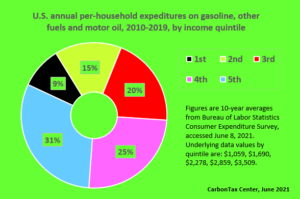

Most middle- and low-income households spend a higher percentage of their income on gasoline, other fuels and electricity than do higher-income households. In 2019, for example, the wealthiest 20% U.S. households spent just 2% of their after-tax income on gasoline; the percentage for the lowest quintile, 8%, was four times as high. Clearly, imposing a gasoline tax or, by implication, a carbon tax, without tax-shifting or dividends will disproportionately burden lower-income families.

Over the past decade, the wealthiest U.S. household quintile has spent 3.3 times as much on gasoline as the poorest.

But expressing energy expenditures in absolute dollar terms is a different and arguably more meaningful measure. Averaged over the 10-year period 2010-2019, the top-echelon quintile spent an average of $3,509 on gasoline, or 3.3 times as much as the $1,059 spent by the poorest 20% of households. Put differently, when all household outlays for gasoline are apportioned among quintiles, the highest-earning quintile accounted for 31% of the total, while the lowest quintile contributed just 9%. (The middle quintile, true to its name, spent exactly 20% of total outlays — see chart.)

What’s true for gasoline applies to energy in general, as the Citizen’s Climate Lobby confirmed in a 2016 report analyzing the short-term financial impact of its fee and dividend idea set at a level of $15 per ton of carbon dioxide. The report painstakingly captures wide geographic variations in the carbon contents of fuels used to generate electricity, among other variables, giving it a finer grain than many previous analyses of carbon tax incidence. It found that households in the top quintile would pay an on average additional $319 per month, directly and indirectly, through higher fossil fuel prices associated with the carbon fee; that’s more than three times the additional $96 per month that households in the lowest quintile would pay. (The middle three quintiles would pay $116, $143, and $183, respectively.)

Although the lowest quintile would bear the greatest burden of the carbon fee as a percentage of household income, it would pay the least in absolute terms. This makes possible a “progressive” outcome through rebates such as CCL’s proposed dividends, or via appropriate tax-shifts. Significantly, the report found that 53% of households (58% of individuals) would receive more through monthly rebates than they would incur from the carbon tax. Even better, the majority of these benefits would be reaped by the most vulnerable, with nearly 90% of households below the poverty line benefiting in net terms from the carbon “fee and dividend” plan. Monthly dividends, in other words, could ensure an equitable and progressive carbon tax.

The bulk of carbon taxes will be paid by families of above-average means

The upward skew in carbon use over the income range comes about because higher-income households don’t just drive more, they also fly more (burning jet fuel), they tend to own bigger (and sometimes multiple) houses to heat and cool, and they buy and use more products that require electricity or industrial fuels to manufacture, deliver and use. This means that the bulk of carbon taxes will be paid, directly or indirectly, by families of above-average means. For the gasoline part of carbon taxes, we estimate that around two-thirds will be paid by above-average-income households (calculated by summing: the first and second quintiles’ shares of gasoline expenditures in the pie chart above, plus half of the middle quintile’s share, yielding a total of 66%; data are from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Expenditure Survey, 2014).

Using carbon tax revenues to cut corporate taxes is problematic

Conservatives who support, or at least are willing to consider, taxing carbon emissions (yes, there are some) fall into two camps on revenue treatment: backing the carbon dividend plan proposed by the Climate Leadership Council (which in turn draws on the fee-and-dividend approach espoused by the Citizens Climate Lobby); or urging that the carbon revenues be applied to reduce the U.S. corporate income tax.

Expert analysis published several years ago by Resources for the Future (which we summarize and link to on our Tax Shifting page) suggested that using carbon tax revenue to reduce corporate income tax rates would benefit middle- and upper-income households but not lower-income families, relatively few of whom own stocks whose share values would rise as corporate tax rates were reduced. Political deals (sometimes dubbed “grand bargains”) to win Republican support for carbon taxes, such as the proposal by Democratic Senators Sheldon Whitehouse (RI) and Brian Schatz (HA) therefore risk alienating labor, low-income advocates and economic-justice activists, many of whom are already tepid at best about carbon tax legislation that doesn’t directly invest considerable carbon revenues in a “just transition.”

Earlier analyses of carbon tax incidence

In 2010, four leading economists released a report detailing the impacts on different income groups of various cap-and-trade carbon pricing proposals. The following is an excerpt from the abstract of Distributional Implications of Alternative U.S. Greenhouse Gas Control Measures by Sebastian Rausch, Gilbert E. Metcalf, John M. Reilly, and Sergey Paltsev, published by the MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Climate Change:

[W]e find that carbon pricing by itself (ignoring the return of carbon revenues through allowance allocations) is proportional to modestly progressive. This striking result … stands in sharp contrast to previous work … The main reason is that lower income households derive a large fraction of income from government transfers and, reflecting the reality that these are generally indexed to inflation, we hold the transfers constant in real terms. As a result this source of income is unaffected by carbon pricing, while wage and capital income is affected.

As the authors suggest, their finding runs counter to conventional economic thinking that consumption taxes (including carbon taxes) are necessarily regressive when revenue treatment is ignored.

Last, a report published by Resources for the Future in October 2013, by Daniel F. Morris and Clayton Munnings, Designing a Fair Carbon Tax, provides a succinct guide to issues of fairness and efficiency in crafting a federal carbon tax.

Inter-Generational Issues

In 2016 the Citizens’ Climate Lobby commissioned a paper analyzing the effects on households of a $15/ton carbon “fee and dividend” plan in which the impacts of higher fossil fuel prices are at least somewhat offset by monthly “dividend” distributions. While the paper’s main thrust was the different impacts on rich, middle-class and poor households (summarized here), it also examined the financial effect by age group.

The CCL paper found that around 2/3 of very young and very old households – ages 18-35 and 80 and above – would experience a net benefit after the monthly dividend payments, compared to 44% of households aged 50-65. These findings reflect the fact that younger and elder households typically have smaller carbon footprints through lower levels of consumption, relative to households in the middle-age groups. Moreover, younger households tend to be relatively larger and thus would receive larger dividends, under the CCL plan.

In a similar vein, economists at the Washington, DC think-tank Resources for the Future considered the generational impacts of a $30/ton carbon tax in a 2013 paper, “Deficit Reduction and Carbon Taxes: Budgetary, Economic, and Distributional Impacts.” Writing at a time when so-called “deficit hawks” still held some sway in public discourse, they concluded that dedicating the carbon tax revenues to deficit reduction would offer particular benefits to the young by reducing tax burdens that might otherwise carry into the distant future.

On the other hand, asking today’s middle-aged and elder Americans to allow carbon tax revenues to be used to shrink the national debt risks compounding the difficulty of passing a carbon tax whose benefits already accrue largely to future generations. If the objective is to assemble a political majority that can pass a robust carbon tax, it may be best to leave deficit reduction off the table in favor of either tax-shifting or revenue return a la fee-and-dividend.

Regional Differences

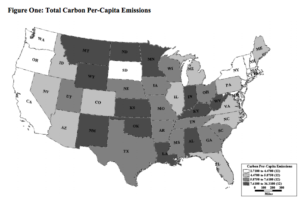

Members of Congress repeatedly voice concern that measures to impose a price on carbon emissions will disproportionately burden energy users in their district or state. “We’re looking for some type of regional equity in whatever they propose,” said Rep. Marcy Kaptur (D-OH) during Energy and Commerce Committee deliberations over the Waxman-Markey climate bill, as reported in the New York Times on May 8, 2009. At a Senate Finance Committee hearing on proposed cap-and-trade legislation, Senator Orrin Hatch (R-UT) complained that a $50/ton CO2 price would increase electric rates by 70% in his state, which relies heavily on coal for electricity.

The root of the issue is variations in regional fuel mix, compounded in some instances by variations in levels of energy use. Electricity rates in the Pacific Northwest, which is generously endowed with hydro-electric power, should scarcely be affected by carbon emissions pricing through either a tax or cap-and-trade system. In contrast, the Plains states, which primarily employ coal for electricity generation, and the Northeastern states, which rely heavily on fuel oil for heating, could face disproportionate impacts. In addition, people in rural areas tend to drive longer distances than city-dwellers, so their transportation costs would be expected to rise more.

Are these regional differences significant? What if any steps should be taken to address them in designing a carbon tax and the accompanying revenue-recycling measures?

A thorough analysis of these questions is “The Incidence of a U.S. Carbon Tax: A Lifetime and Regional Analysis” (January 2008). In this AEI working paper, economists Kevin A. Hassett, Aparna Mathur and Gilbert E. Metcalf estimated the incidence of a carbon tax of $15 per metric ton of CO2 imposed “upstream” on fuel producers and importers. They defined the direct component as the increased cost of gasoline, home heating and electricity. The indirect component is the increased cost of other goods, ranging from air travel to food purchases, resulting from the higher cost of fuel used in their provision. The two components are of similar magnitude, but the indirect component doesn’t vary much across the U.S., reflecting our national market for consumer products.

Hassett et al. chose the household as the unit of consumption and considered the lifetime incidence of the tax. Taking both direct and indirect impacts into account, Hassett et al. calculated that in 2003 the largest variation between regions was less than 0.37% of household income. (This was less than the maximum regional differences in the two other years chosen for the analysis — 0.42% in 1987, and 0.89% in 1997.) They concluded:

Carbon taxes are… thought to have uneven regional effects. We … find that the regional variation is at best modest. By 2003 variation across regions is sufficiently small that one could argue that a carbon tax is distributionally neutral across regions.

The U.S. Census Bureau reports that the median U.S. household income in 2006 was $48,201. Thus, the 0.37% difference represents a difference of just $178 per year between typical households in the most affected and the least affected regions. The average interregional difference is much less.

Nevertheless, aggregated over millions of households this difference could be significant, especially if, as we and some others urge, a carbon tax (or cap-and-trade system) quickly attains and surpasses the relatively modest carbon emissions price level assumed in the Hassett analysis.

More recently, in “The Incidence of U.S. Climate Policy: Alternative Uses of Revenues from a Cap-and-Trade Auction” (Resources for the Future, April 2009), Dallas Burtraw, Richard Sweeney, and Margaret Walls examined income and distributional effects (across eleven regions) of an emissions cap with auctioned permits that resulted in a price of $20/ton CO2. (The regional incidence of a carbon tax would mirror that created by pricing carbon emissions using a cap.) They considered distributional effects on an annual basis which tends to magnify disparate impacts between income groups (and may also magnify regional differences) in contrast to Hassett et al.’s lifetime incidence analysis which tends to minimize them.

Burtraw et al. found that “putting a price on CO2 emissions can distribute costs unevenly across income groups and regions, and that revenue allocation decisions can either temper or exacerbate these distributional effects.” They found that, compared to revenue recycling via reduced payroll tax rates, a direct “dividend” approach would result in slightly larger net regional differences, especially in the lowest income groups. Yet even those differences would amount to no more than 2% of total annual income, assuming the $20/ton CO2 price.

Disparate impacts on households across regions can be compounded by regional differences in impacts on energy-intensive industries and their workers. For example, while energy consumers in coal-mining states might be affected only slightly more than those in other states, workers who mine, process or transport coal would face far larger impacts as a carbon tax (or cap) shifted employment and investment from coal to low-carbon alternatives. The flip side, of course, is that the same carbon tax or cap would benefit workers in areas with abundant renewable resources. A state like Montana, with both coal and wind resources, might be a net employment gainer under a carbon tax as construction and operation of wind generation facilities increased; but its coal workers would still need transition assistance.

Policy Options

Prof. Metcalf suggests a way to mitigate distributional disparities: adjust the amounts of revenue recycled according to the average regional carbon tax burden. For instance, if households in the Pacific Northwest would indeed pay less in carbon taxes than the national average, individuals or households in that region would receive proportionately lesser payroll tax reductions or direct distributions of revenue. Households in the Plains states might receive a correspondingly greater share of the recycled revenue. In this way, a revenue-neutral carbon tax could be regional-neutral as well.

To address disparate impacts on energy-intensive industries, Congressman Larson’s proposal designates 1/12 total of initial carbon tax revenues to assist affected workers and industries. (This “transition assistance” would be phased out over a decade.) A different approach in cap-and-trade legislation introduced by Reps. Inslee and Doyle — granting free allowances to “energy-intensive, trade-exposed” industries — would appear to mute the very price signal that such industries require to reduce emissions.

Other regional and affected-industry adjustments — hopefully temporary — could be made under either a carbon tax or cap-and-trade. We believe that under an explicit carbon tax they would be far simpler, more transparent and less likely to undermine carbon reduction incentives.

A Contrasting Analysis

In May 2009, economists Michael Cragg (UCLA) and Matthew E. Kahn (The Brattle Group) published a fascinating analysis correlating county-level CO2 emissions with the political beliefs and climate-policy voting records of Members of Congresss. Their paper, Carbon Geography: The Political Economy of Congressional Support for Legislation Intended to Mitigate Greenhouse Gas Production, finds that:

[C]conservative, poor areas have higher per-capita carbon emissions than liberal, richer areas. Representatives from such areas are shown to have much lower probabilities of voting in favor of anti-carbon legislation. In the 111th Congress, the Energy and Commerce Committee consists of members who represent high carbon districts. These geographical facts suggest that the Obama Administration and the [Energy & Commerce] Committee will face distributional challenges in building a majority voting coalition in favor of internalizing the carbon externality.

The Cragg-Kahn analysis appears to have been prescient, with the Waxman-Markey bill laden with free allowances, “clean coal” RD&D funds, and other emoluments that won just enough support from Democrats representing high-carbon districts to win the bill’s passage in June 2009. However, unlike the AIF and RFF papers discussed above, the Cragg-Kahn paper is not an “incidence” analysis. This is because its unit of analysis (statistically, the “dependent variable”) was carbon emissions rather than carbon consumption.

Thus, the analysis assigned 100% of carbon emissions from power plants to the counties and districts where the plants are located, rather than allocating them to end-use customers — the households, offices and facilities that purchase the electricity and will pay the carbon tax or emission permit fees as they are passed through the supply chain. It therefore could not depict precisely how carbon emissions pricing will add differently to expenditures in one county or state versus another. Nevertheless, we commend the Cragg-Kahn paper as a provocative piece of political economy, along with John Kemp’s Reuters column, Carbon Geography of the United States, that brought the paper to our attention.

Another Thoughtful Analysis

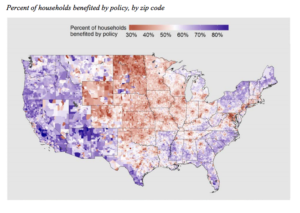

A Nov. 3, 2009 post on The New Republic’s Vine blog, Cap and Trade Costs: Place Matters, featured a map that grouped U.S. metropolitan areas into quintiles according to the per-household cost impact of proposed cap-and-trade bills. The authors noted:

The household costs of cap-and-trade compliance … depend quite a bit on what metro you live in. Ranging above and below the average $160 cost to a household nationally in 2020, the average metro figures range from a high of $277 per household in Lexington, KY to a low of just $96 in Los Angeles. Low costs are registered all across the West’s metros and in Northeastern metros like New York, Boston, and Rochester. Much higher costs will be borne by households in metros all across the upper South and Ohio Valley—places like Cincinnati, and Indianapolis, and Nashville. So once again, as we keep saying: Place matters.

The map, credited to the Brookings Institution, is worth studying. Also worth pondering is the authors’ conclusion:

[R]egions that want to do well for their citizens might want to manage growth a little better, provide transportation options, and think about cleaning up their energy sourcing.