(Feb. 2020): Oil and Gas May Be a Far Bigger Climate Threat Than We Knew (NYT)

Oil and gas production may be responsible for a far larger share of the soaring levels of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, in the earth’s atmosphere than previously thought, new research has found.

The findings, published in the journal Nature, add urgency to efforts to rein in methane emissions from the fossil fuel industry, which routinely leaks or intentionally releases the gas into air.

“We’ve identified a gigantic discrepancy that shows the industry needs to, at the very least, improve their monitoring,” said Benjamin Hmiel, a researcher at the University of Rochester and the study’s lead author. “If these emissions are truly coming from oil, gas extraction, production use, the industry isn’t even reporting or seeing that right now.”

Full Feb. 19, 2020 story here.

New (March 2022): Methane Leaks in New Mexico Far Exceed Current Estimates, Study Suggests (NYT)

An analysis of aerial data by two researchers at Stanford University found that leaks of methane from oil and gas drilling in the Permian Basin were many times higher than government estimates, suggesting that oil and gas industry operations may be contributing far more to climate change than implied in official estimates.

The largest prior assessment of methane emissions from oil and gas in the United States, published in 2018, reviewed studies covering about 1,000 well sites, a tiny fraction of the more than one million active wells in the country. The new study, which was published Wednesday in the journal Environmental Science & Technology, used aerial data to examine nearly 27,000 sites from above: more than 90 percent of all wells in the New Mexico portion of the Permian Basin, which also extends into Texas.

The researchers also took measurements from each site on multiple occasions to account for the fact that operations, and therefore emissions, vary over time. Methane can be released by wells both on purpose, in a process known as venting, and through unintentional leaks from aging or faulty equipment.

Their syudy calculated methane emissions at 9.4 percent of gross gas production, which dwarfs the Environmental Protection Agency’s 1.4 percent estimate. It also exceeds the methane leakage “break-even point” — the point above which burning natural gas would cause even more damage than burning coal — estimated by Dr. Robert Howarth, a professor of ecology and environmental biology at Cornell University. Howarth, who a decade ago helped sound the alarm about methane emissions from fossil fuel extraction, processing and transport, recently put the threshold at 2.8 or 2.9 percent.

The Standford team found that a small number of wells and pipelines accounted for “the vast majority” of methane leaks, said one of the researchers, Yuanlei Chen, a Ph.D. student in energy resources engineering, adding, “Comprehensive point source surveys find more high-consequence emission events, which drive total emissions.”

If there was good news in the study, it was that a small number of oil and gas sites contributed disproportionately to emissions — suggesting that, if the worst offenders change their practices, it is possible for the industry to operate more cleanly.

Full March 24, 2022 story here.

The remainder of this page was researched and written by Analee Graig, a CTC 2016 summer intern and student at SUNY-Binghamton.

CH4, or methane, is a colorless, odorless gas widely found in nature. Like carbon dioxide, it is a potent greenhouse gas contributing to global warming. Pounds for pound, methane traps far more heat while it is in the atmosphere than does CO2. Over a twenty-year period, a molecule of methane is estimated to be 84 times more powerful a climate-change agent than a molecule of CO2.

Fortunately, molecules of methane dissipate naturally from the atmosphere in around a dozen years, on average, whereas the mean atmospheric residence time of CO2 is far longer, around a century. On a 100-year time scale, then, methane is considered “only” 25 times as potent per pound as CO2 at warming the climate, though its potency looms larger in short time horizons that are sometimes used in climate policy. Nevertheless, because of the far greater volume of CO2 emissions, methane is generally assigned a secondary role in climate analysis and policy.

Methane is produced naturally in anaerobic environments by bacteria that feed on decomposing organic matter. Wetlands are a prominent source of atmospheric methane and are responsible for roughly 25% of total CH4 emissions. The natural digestive processes of ruminant animals such as cows also result in release of methane. While methane occurs naturally in the earth, human activities, such as industrial agriculture practices and natural gas production, are responsible for over 60% of global methane emissions. It is that share that we can and should address through policy.

Methane is produced naturally in anaerobic environments by bacteria that feed on decomposing organic matter. Wetlands are a prominent source of atmospheric methane and are responsible for roughly 25% of total CH4 emissions. The natural digestive processes of ruminant animals such as cows also result in release of methane. While methane occurs naturally in the earth, human activities, such as industrial agriculture practices and natural gas production, are responsible for over 60% of global methane emissions. It is that share that we can and should address through policy.

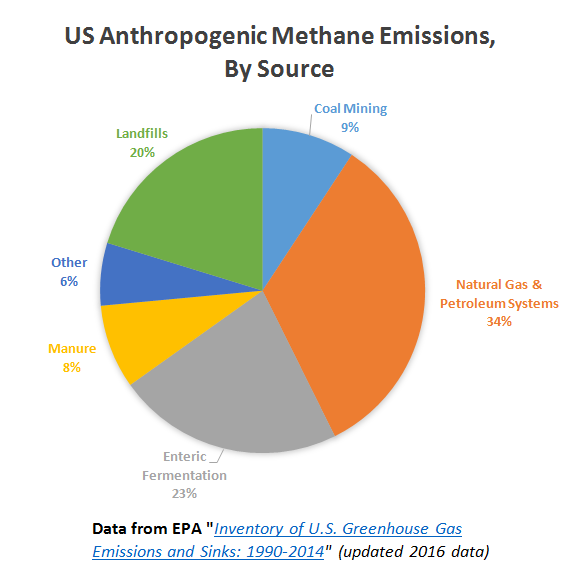

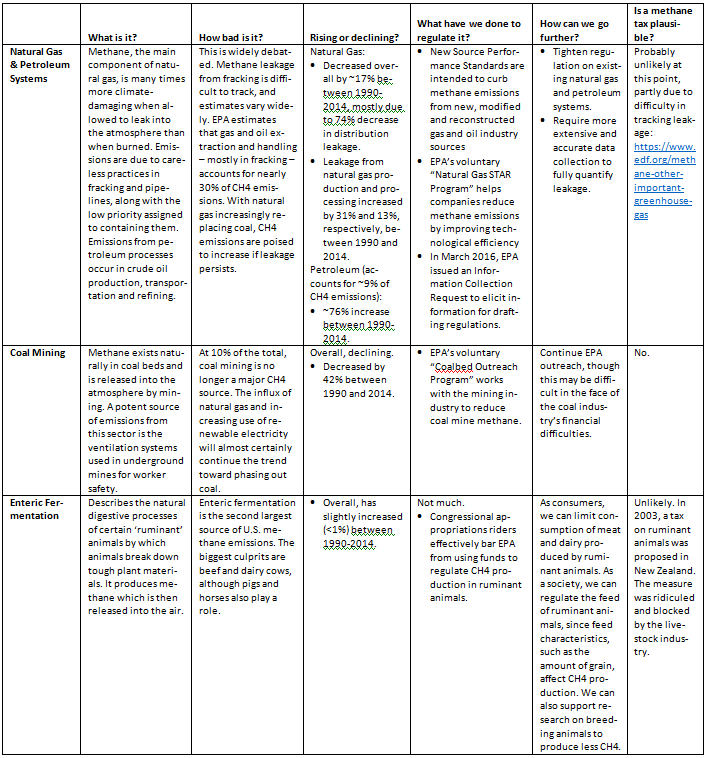

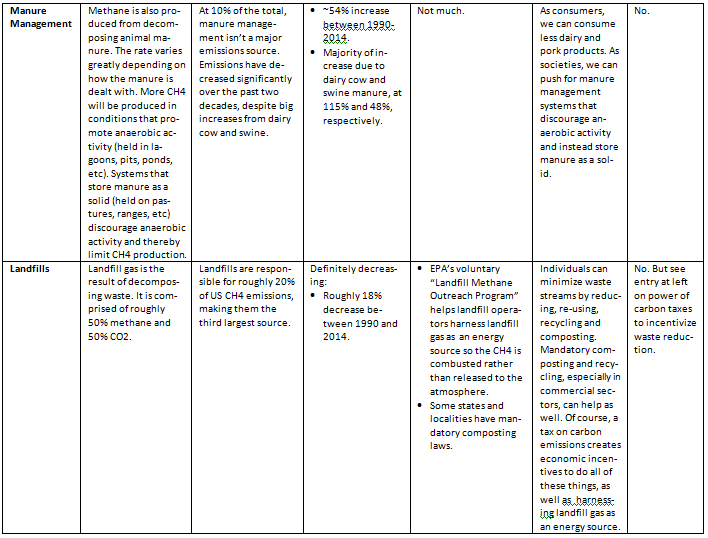

In U.S. EPA’s meticulous accounting of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions, methane accounted for 10.6% of the U.S. total in 2014, a distant second after carbon dioxide’s 80.9%. No single methane source dominates, but the largest category is fossil fuel extraction, which in 2014 accounted for an estimated 43% of methane emissions, with 34% from extracting and transporting natural gas and petroleum, and 9% from coal mining. The next two largest sources are livestock, at 31%, with 23% from enteric fermentation and 8% from manure, and landfills (20%).

Methane’s usefulness as an energy source creates a strong but incomplete incentive to reduce its emission to the atmosphere — incomplete because the climate consequences of methane emissions aren’t reflected in its energy or commercial value. Further, emissions are projected to rise as natural gas takes market share from both coal and oil.

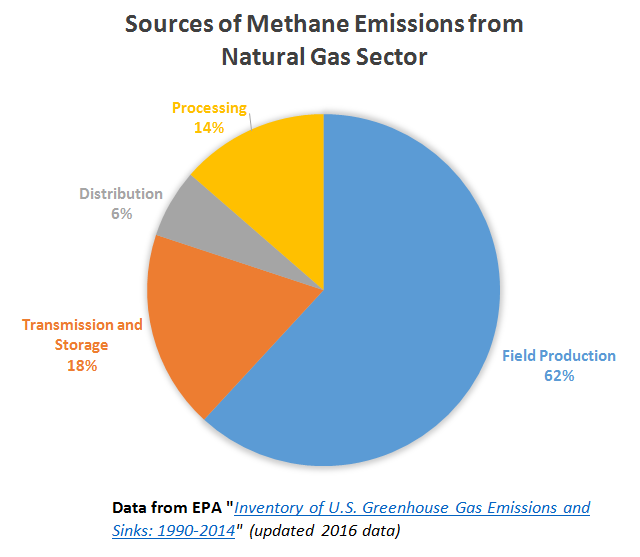

EPA’s efforts to reduce methane reduction have historically focused on voluntary programs, such as the Natural Gas STAR Program and the Landfill Methane Outreach Program, that encourage companies to reduce emissions and therefore save money. However, the success of such programs is widely debated. The National Resources Defense Council has found that most participants in EPA’s Methane Challenge Program, developed in 2016, are natural gas distribution companies, even though the natural gas distribution sector accounted for only 6% of the gas industry’s 2014 emissions.

Recently, EPA’s response’s has shifted to more “command-and-control” regulations as better data collection has revealed the growing seriousness of methane leakage from the oil and gas sector.

Recently, EPA’s response’s has shifted to more “command-and-control” regulations as better data collection has revealed the growing seriousness of methane leakage from the oil and gas sector.

In 2014, as part of its Climate Action Plan, the Obama administration issued a series of ‘white papers’ on methane emissions in the gas and oil sector. These led to proposed EPA regulations, published in May 2016, to limit emissions in gas and oil production.EPA also issued an Information Collection Request (ICR) aimed at collecting detailed data on methane leakage to guide further regs.

However, EPA’s ability to regulate the oil and gas industry is limited, partly because considerable regulatory authority has been delegated to states, and also because petroleum-state members of Congress have been able to pass legislative riders limiting EPA’s ability to act.

The table below summarizes the chief sources of U.S. methane emissions from human activity.

Editor’s Note: For another solid summary of methane chemistry and policy, take a look at Yale Climate Connections’ August 2016 post, Is Natural Gas a Bridge Fuel? It takes a smart look at CO2 vs. CH4 and coal vs. natural gas, as well as fossil fuels vs. renewables.