- Environmental Taxation and the Double Dividend (Lawrence Goulder, Stanford, 1994). Seminal articulation of the dual benefits of replacing taxes on income and work with taxes to discourage pollution.

- When Can Carbon Abatement Policies Increase Welfare? The Fundamental Role of Distorted Factor Markets (Ian Parry, Roberton Williams & Lawrence Goulder, Resources for the Future, 1998). General equilibrium modeling demonstrates economic efficiency benefits of pollution taxes with revenue “recycling” to reduce marginal rates of pre-existing distortionary taxes.

- Clean Energy And Jobs: A comprehensive approach to climate change and energy policy (James P. Barrett & J. Andrew Hoerner, Economic Policy Institute, 2002).

- A Proposal for a U.S. Carbon Tax Swap (Gilbert Metcalf, Brookings, 2007).

- Caps vs. Taxes (Kevin Hassett, Steven Hayward, Ken Green, AEI, 2007).

- U.S. Federal Climate Policy and Competitiveness Concerns: The Limits and Options of International Trade Law, Joost Pauwelyn, Duke U., 2007). WTO rules permit “border tax adjustments” (import tariffs) to harmonize domestic carbon taxation. [Updated, March 2012.]

- Smart Taxes: An Open Invitation to Join the Pigou Club (Greg Mankiw, Harvard, 2008).

- Policy Options for Reducing CO2 Emissions (Congressional Budget Office, 2008). “[T]he net benefits (benefits minus costs) of a [carbon] tax could be roughly five times greater than the net benefits of an inflexible cap.”

- CO2 Price Volatility: Consequences and Cures (Brattle Group, January 2009).

-

On Modeling and Interpreting the Economics of Catastrophic Climate Change (Martin Weitzman, Harvard, 2009).

- Addressing Climate Change Without Impairing the US Economy (Robert Shapiro, US Climate Task Force, 2008).

- On The Merits of A Carbon Tax (Ted Gayer, Brookings, Testimony to Senate Env’t & Nat’l Res. Committee, 2009).

- The Design of a Carbon Tax (Gilbert Metcalf & David Weisbach, Harvard Envt’l Law Rev, 2009).

- Carbon taxation – a forgotten climate policy tool? (Global Utmaning [Sweden], 2009)

-

Carbon Tax and Greenhouse Gas Control: Options for Congress, (Jonathan Ramseur & Larry Parker, Congressional Research Service, 2009). Options for design and implementation of U.S. carbon tax to match emissions reductions from Lieberman-Warner (cap & trade) bill without price volatility, speculation and offsets.

- How Climate Policy Could Address Fiscal Shortfalls (Adele Morris & Ted Gayer, Brookings, 2010).

- A Balanced Plan to Stabilize Public Debt and Promote Economic Growth (William Galston, Brookings & Maya MacGuineas, Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, 2010). Recommendations include a broad-based carbon tax with proceeds to reduce payroll taxes and for deficit reduction.

-

Carbon pricing in Washington (Yoram Bauman, Sightline Institute, 2010). Quantitative economic and climate policy “blueprint” for Carbon Washington revenue-neutral carbon tax proposal.

- Moving U.S. Climate Policy Forward: Are Carbon Taxes the Only Good Alternative? (Ian Parry & Roberton Williams, Resources for the Future, 2011).

- Revising the Social Cost of Carbon, (Frank Ackerman & Elizabeth Stanton, E3 Network, 2011).

- Carbon Taxes, An Opportunity for Conservatives (Irwin Stelzer, Hudson Institute, 2011).

- Fiscal Solutions: A Balanced Plan for Fiscal Stability and Economic Growth, Peterson Foundation & American Enterprise Institute, 2011). As part of comprehensive reform, recommends replacing ethanol subsidies and greenhouse gas regulations with a $26/tonne CO2 (and CO2-eq) tax, rising 5.6% annually. (p 25.)

- The Potential Role of a Carbon Tax in U.S. Fiscal Reform (Brookings, 2012)

- Offsetting a Carbon Tax’s Costs on Low-Income Households (CBO, 2012)

- Considering a U.S. Carbon Tax: Frequently Asked Questions (Resources for the Future, 2012)

- Carbon Tax Revenue and the Budget Deficit: A Win-Win-Win Solution? (MIT, August 2012)

- It’s Time for a Carbon Tax (Elizabeth Kolbert, The New Yorker, Dec. 10, 2012)

- Fiscal Policy to Mitigate Climate Change (IMF, 2012)

- The Many Benefits of A Carbon Tax (Adele Morris, Brookings, 2013)

-

Carbon Taxes and Corporate Tax Reform (Donald Marron & Eric Toder, Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, 2013)

- Reaffirming the Case for a Briskly Rising Carbon Tax (James Handley, Carbon Tax Center, June 2013)

-

Changing Climate for Carbon Taxes: Who’s Afraid of the WTO? (Jennifer Hillman, German Marshall Fund, Climate Advisors, American Action Forum, July 2013).

- Can Negotiating a Uniform Carbon Price Help to Internalize the Global Warming Externality? (Martin Weitzman, Harvard Project on Climate Agreements, January 2014).

- Design of Economic Instruments for Reducing U.S. Carbon Emissions, (Carbon Tax Center, submitted to Senate Finance Committee, January 2014).

- Tax Policy Issues in Designing a Carbon Tax (Donald B. Marron and Eric J. Toder, Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, May 2014).

-

A Carbon Tax in Broader U.S. Fiscal Reform: Design and Distributional Issues, Adele Morris (Brookings) and Aparna Mathur (American Enterprise Institute), C2ES, May 2014.

-

Temperature impacts on economic growth warrant stringent mitigation policy, Frances C. Moore, Delavane B. Diaz (Nature Climate Change, January 2015). When climate change is allowed to affect economic growth in the DICE Integrated Assessment Model, its estimate of the Social Cost of Carbon may exceed $220/T CO2.

- How to Adopt a Winning Carbon Price — Top Ten Takeaways from Interviews with the Architects of British Columbia’s Carbon Tax (Clean Energy Canada, 2015).

-

Putting a Price on Carbon: A Handbook for U.S. Policymakers, Kevin Kennedy, Michael Obeiter, Noah Kaufman (World Resources Institute, April 2015).

-

Energy Subsidy Reform, Lessons and Implications (International Monetary Fund, May 2015).

-

Taxing Carbon: What, Why, and How, by Donald Marron, Eric Toder, and Lydia Austin, (Tax Policy Center, June 2015).

-

Global Carbon Pricing: We Will If You Will (September 2015). E-book compilation of eight papers by David J. C. MacKay, Richard Cooper, Joseph Stiglitz, William Nordhaus, Martin L. Weitzman, Christian Gollier & Jean Tirole, Stéphane Dion & Éloi Laurent, Peter Cramton, Axel Ockenfels & Steven Stoft. The authors, from a variety of viewpoints and disciplines, conclude that negotiating an explicit global price on carbon pollution would help unlock global climate negotiations by aligning national self-interest with the global goal of rapidly reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

-

After Paris: Fiscal, Macroeconomic, and Financial Implications of Climate Change (IMF discussion draft, January 2016).

Search Results for: ken green

The Carbon Tax Revenue Menu

Getting the politics to align for a carbon tax requires the right blend of honey and vinegar. For years, advocates’ and opponents’ attention alike has focused on the vinegar – the tax part. Lately, though, we’ve noticed growing interest about how to best spread the honey — the potentially huge revenues a carbon tax would generate. Here’s a primer on the options: what they are, how they would work, their merits and drawbacks, and who’s pushing them hardest.

Setting the initial tax rate at $15/T CO2 and increasing it by that amount each year (reflecting the maximum carbon tax rate and ramp-up of Rep. Larson’s bill) we estimate that the Treasury would take in approximately $80 billion in revenue in the first year. (This calculation uses the Carbon Tax Center’s spreadsheet model.) This amount would rise each year, though at slightly less than a linear rate as carbon reductions kicked in, reaching around $600 billion by the tenth year.

The allure of carbon tax revenue also offers a growing incentive for other nations to match a U.S. carbon tax in order to avoid WTO-sanctioned border tax adjustments, capturing the revenue themselves. Indeed, Brookings economist Adele Morris calls a carbon tax a “two-fer” because along with a growing revenue stream would come substantial CO2 emissions reductions. For the U.S., based on historic price-elasticities, CTC’s model projects a 30% reduction in climate-damaging CO2 emissions by the tenth year, compared to 2005 levels.

Six hundred billion (again, that’s the projected take in the tenth year from an ambitious carbon tax) is a lot of revenue, equivalent to around a quarter of federal tax receipts. As Ian Parry and Roberton Williams recently explained in “Moving U.S. Climate Policy Forward: Are Carbon Taxes the Only Good Alternative?” (Resources for the Future), the efficiency advantages of a carbon tax depend on using the revenue wisely. Not surprisingly, there are loads of claimants. Here’s a guide to the most prominent ones, sequenced more or less from the political left to right:

a) “Dividend.” Climate scientist James Hansen contends that to support a steadily-rising CO2 price, the public needs to see the money — every month. He calls his proposal “fee & dividend.” Senators Cantwell (D-WA) and Collins (R-ME) introduced the “CLEAR” bill which uses “price discovery” via a cap to set its carbon tax which would begin at a price between $7 and $21/T CO2, increasing 5.5% each year. CLEAR would return 75% of revenue via direct “dividends” and dedicate the remaining 25% to a fund for transition assistance and reduction of non-CO2 emissions. Rep. Chris Van Hollen (D-MD) also introduced a cap & dividend bill in the Ways & Means Committee. It relies on a cap to set the CO2 price indirectly, aiming for 85% reductions (over 2005 levels) by 2050. Because of its similar emissions trajectory, we’d expect Van Hollen’s bill to generate similar revenue to Rep. Larson’s bill: roughly $80 billion in the first year, rising to about $600 billion within a decade. Both the CLEAR bill and the Van Hollen bill bear the intellectual and organizing stamp of social entrepreneur Peter Barnes, who founded “Cap & Dividend,” and Peter’s allies including the Chesapeake Climate Action Network.

b) Payroll tax rebate. Rep. John Larson’s “America’s Energy Security Trust Fund Act” pairs a carbon tax with rebates of payroll taxes on earnings. As articulated by Tufts University economist Gilbert Metcalf (now serving at the Treasury Department’s energy office), Larson’s proposal has the appeal of broad fairness. It would distribute revenue very evenly across both income and regions. Because Rep. Larson’s approach rebates payroll taxes via a credit on federal income taxes — it would rebate the payroll tax on the first $3600 of income in the first year, with that threshold and rising over time — it avoids tangling with the Social Security Trust fund.

Economist and former Undersecretary of Commerce Rob Shapiro supports the approach of a payroll tax rebate, arguing that cutting payroll taxes could spur job growth. Social entrepreneur Bill Drayton, founder of “Get America Working,” is also a strong advocate of using carbon revenue to cut payroll taxes in order to stimulate employment while reducing emissions. Al Gore captured the idea with the phrase, “tax what we burn, not what we earn.” Former Rep. Bob Inglis (R-SC) introduced the “raise wages, cut carbon” bill co-sponsored by Rep. Jeff Flake (R-Az). Conservative economists Greg Mankiw and Douglas Holtz-Eakin, both of whom have advised Republican presidents and candidates, have also supported shifting tax burdens from payrolls to carbon emitters. And the Progressive Democrats of America endorsed the Larson bill.

c) Deficit reduction. Brookings economists including Ted Gayer and Adele Morris have been pointing out the potential for climate policy to reduce deficits. While deficit reduction isn’t revenue return in the immediate sense that Dr. Hansen suggests, Morris points out that deficit reduction will benefit future taxpayers by paying down at least part of the nation’s debt, rather than letting it continue accumulating interest. In this way, she suggests, the impulse to help future generations via foresighted climate policy would have a natural fiscal correlative of reducing future tax burdens.

Supporters of applying carbon tax revenues to deficit reduction include MIT’s Michael Greenstone (chair of the Brookings Hamilton Project on climate and energy policy) and Alice Rivlin, founding director of the Congressional Budget Office, who co-chaired the Bipartisan Policy Institute’s alternative to the Obama deficit commission. Prof. Metcalf proposed a carbon tax to the commission, with revenue return as “transition assistance” in the early years, shifting to deficit reduction in later years. As Irwin Stelzer of the conservative Hudson Institute recently pointed out, when the options to close budget gaps sift down to unpopular alternatives such as a value added tax (regressive and annoying, as EU residents will attest) or curbing home mortgage deductions, a carbon tax may emerge with greater appeal. While Keynesians argue that the present weak economy militates against any net increase in taxes, a phased-in allocation of carbon tax revenues to deficit reduction such as Prof. Metcalf proposes may circumvent that objection.

d) Income tax cuts. Greg Mankiw has suggested cutting income taxes as an alternative to payroll tax cuts to return carbon tax revenues; those Form 1040’s could include a carbon rebate drawn from those revenues for every taxpayer. Revenue could be returned via a lump sum credit (which would be income-progressive) or by reducing income tax rates (arguably more stimulative of income-earning activity).

e) Corporate income tax (CIT) rate cut. At a recent AEI event “Whither the Carbon Tax,” AEI economist Kevin Hassett argued for a carbon tax paired with a reduction in the corporate income tax rate. The Wyden-Coates tax reform bill proposes to reduce top CIT rates and make up the revenue by closing numerous exemptions, indicating interest on the Hill. Adherents of CIT rate cuts point to IMF studies saying that U.S. CIT rates are among the world’s highest, asserting that these taxes are especially stifling of business activity and employment. Hassett and his AEI collegue Aparna Mathur argue that CIT’s are passed through as higher prices for consumers and passed back to the factors of production: labor (in the form of reduced wages) and capital (in the form of reduced corporate earnings). They estimate that using carbon tax revenue to cut the effective CIT rate would result in return of about 40% of revenue to wage-earners, which they assert would give the CIT to carbon tax shift a net progressive effect. Their conclusion may be a stretch, given that real wages have remained stagnant or fallen for decades while corporate profits are rising briskly, but a CIT cut has strong salience for conservatives and business leaders.

f) The sampler platter. The options listed above can be mixed and matched. In fact, British Columbia’s carbon tax (which started at $10/t CO2 in 2008 and rises $5/t each year — it notches up to $25 per metric ton on July 1) launched with a distribution of a $100 direct “dividend” to each taxpayer even before the carbon tax was levied, and is now returning revenue via cuts in payroll, income and corporate tax rates. Former BC Premier Gordon Campbell was re-elected to a third term in 2009 after enacting the carbon tax with this mix of revenue return measures, perhaps indicating that a diverse approach to revenue return can have broad and sustained appeal.

Each of the revenue options has important economic and political advantages as well as disadvantages. At the June 1 AEI event, Kevin Hassett decried Senator Cantwell’s direct “dividend” as “terrible policy” because it foregoes the efficiency advantage of using carbon tax revenue to reduce or possibly eliminate other taxes that dampen economic activity. In 2007 Hassett and his AEI colleague Ken Green published an essay aguing for a carbon tax shift as a “no regrets” policy for conservatives, because its tax reform benefits would make it worthwhile even without climate benefits. They pointed to the work of Stanford’s Lawrence Goulder who concludes that the benefit of reducing other distortionary taxes can be large enough to offset some or all of the dampening effect of adding a carbon tax, a phenomenon known as a “double dividend.”

Still, the potential political attractiveness of direct distribution of revenue can hardly be overstated. Dr. Hansen is no politician and doesn’t claim to be an economist, but he sticks to the “dividend” or “green check” while noting that because of its clear and briskly rising price, Rep. Larson’s approach is nevertheless the best climate option on the table. Rep. Van Hollen, outgoing chair of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, certainly knows a thing or two about politics, and Senator Cantwell very effectively made the case for her “cap & dividend” approach last month at Brookings. But even she seems to be looking at other items on the revenue return menu. For the first time, she suggested appropriating some carbon revenue for deficit reduction, confirming that as high summer arrives in Washington, fiscal matters remain the topic for this Congress.

Photo: Flickr.

Memo to Sen. Kerry: Climate Science Includes Economics

U.S. climate activists are gleeful at Sen. John Kerry’s demolition of a sometime climate skeptic at a Senate Finance Committee hearing on Tuesday, and justly so. Ken Green, a resident scholar for the corporate-financed American Enterprise Institute, won the respect of carbon tax advocates two years ago, when he co-authored an AEI report that powerfully made the case for a revenue-neutral carbon tax over a cap-and-trade system. But as an invited witness on Climate Change Legislation: Considerations for Future Jobs, Green attempted to argue that Earth’s ecosystems and human civilization could safely accommodate a global temperature rise of 2 degrees Celsius, though he admitted that any larger temperature rises would be dangerous. Kerry skillfully “outed” Green as an amateur in climatology who had published no peer-reviewed studies and could point to none to support his climate blandishments.

The interchange, summarized in a 6½-minute video assembled by Joe Romm at Climate Progress, showcases Sen. Kerry’s skill as a cross-examiner and reveals just how flimsy and muddled the case questioning the climate crisis really is. Lost in the euphoria, however, is evidence of the Senator’s own confusion — not on the need to act to avert climate catastrophe, but on the workings of competing means of pricing carbon emissions.

In an earlier part of this week’s hearing, Sen. Kerry repeated a point he made in an August 4 Finance Committee hearing on Climate Change Legislation: Allowance and Revenue Distribution: a carbon tax wouldn’t reduce emissions, Kerry claimed, because polluters would “just pay the tax,” whereas a cap would force them into making the desired reductions.

In an earlier part of this week’s hearing, Sen. Kerry repeated a point he made in an August 4 Finance Committee hearing on Climate Change Legislation: Allowance and Revenue Distribution: a carbon tax wouldn’t reduce emissions, Kerry claimed, because polluters would “just pay the tax,” whereas a cap would force them into making the desired reductions.

Of course, as anyone versed in climate economics knows, and as the economist-witnesses explained in August, a carbon price of, say, $20/ton would produce the same emissions reductions whether the price was set by traders in a carbon market or directly via a fee on fossil fuel producers. Under a cap with a $20/ton permit price, emitters would have no greater (and no less) incentive to reduce emissions than they would under a $20/ton tax. Reductions that can be made for up to $20 per ton will be made in either system because they will yield the same savings — as permits that wouldn’t need to be purchased under a cap, or as taxes that wouldn’t have to be paid under a tax. Similarly, reductions costing more than the set price won’t be made because it will be cheaper to “just buy the permits” (to adapt Sen. Kerry’s phrase), or “just pay the tax.”

Under either system, then, emitters retain the flexibility to make reductions when those reductions are cheaper than the carbon price and to pay the allowance cost or tax if that turns out to be cheaper. That flexibility about where, when and how to make reductions is why either a carbon cap or tax is more efficient than source-specific regulations which would force emissions reductions at times and places where they’re more expensive and would miss some reductions that were cheaper.

In the August hearing, Sen. Kerry questioned whether American businesses and households would actually respond to higher fuel and energy prices. In doing so, Sen. Kerry overlooked the vast body of evidence quantifying price-elasticity in virtually every sector of the U.S. economy. He also had evidently forgotten what happened during the summer of 2008 when gasoline hit $4/gallon: traffic congestion eased, carpools, buses and trains filled up, and SUV sales tumbled. And that was only the short-term effect of a price spike; a long-term, predictable carbon emissions price increase would allow sound business planning and create incentives for long-term investment in energy efficiency and low-carbon alternatives.

And that points to a key reason that cap-and-trade is an inferior way to set a price on carbon: the price signal under a cap would be “noisy” due to both volatility and the fact that the price must be “revealed” through the market workings of the cap rather than being stated, explicitly, in the tax code. That noise means that with cap-and-trade it takes a higher price for the economy to “hear it” and respond, even if the general trend is upward.

Sen. Kerry is on solid ground relying on peer-reviewed climate science. But his ongoing misunderstanding of the workings of carbon pricing is almost as shocking as the AEI witness’s misrepresentation this week of climate science. It’s past time for both sides to get it right: The consequences of unmitigated climate change will be grave, whereas clear, simple, predictable carbon pricing is essential to catalyzing the solutions.

Photo: Flickr / The Minnesota Independent

Happy New Year – A New Political Reality for Carbon Taxes

For too long the conventional wisdom has been that while carbon taxes may be superior to cap-and-trade schemes, there is no way that politicians would ever support a new tax, even one that was revenue-neutral. Environmentalists who might otherwise be supporting a carbon tax because it could produce real reductions in greenhouse gas emissions far more rapidly than cap-and-trade have dismissed carbon tax advocacy as naive and have rallied behind cap-and-trade.

Just as conventional wisdom was consistently proven wrong in the 2008 presidential election, it’s also proving wrong about the political infeasibility of a carbon tax. Just look at events over the past two days.

Just as conventional wisdom was consistently proven wrong in the 2008 presidential election, it’s also proving wrong about the political infeasibility of a carbon tax. Just look at events over the past two days.

On Saturday, the lead editorial in the New York Times, The Gas Tax, made a compelling case that the president-elect and Congress should impose a “gas tax or similar levy to keep gas prices up after the economy recovers from recession.”

On Sunday, two prominent Republicans, Congressman Bob Inglis of South Carolina and supply-side economist Arthur Laffer, unequivocally endorsed a U.S. carbon tax in a New York Times op-ed, An Emissions Plan Conservatives Could Warm To, that concisely summarized the politics of climate change and the rationale for a carbon tax from a conservative perspective:

Conservatives don’t support tax increases that are veiled as “cap and trade” schemes for pollution permits. But offer us a tax swap, and we could become the new administration’s best allies on climate change.

The Inglis/Laffer summary of why the Liberman-Warner cap-and-trade bill failed is short and to the point:

A climate-change bill withered in Congress this summer because families don’t need an enormous, and hidden, tax increase. If the bill’s authors had instead proposed a simple carbon tax coupled with an equal, offsetting reduction in income taxes or payroll taxes, a dynamic new energy security policy could have taken root.

Inglis/Laffer cogently present the economic basis for a carbon tax:

We need to impose a tax on the thing we want less of (carbon dioxide) and reduce taxes on the things we want more of (income and jobs). A carbon tax would attach the national security and environmental costs to carbon-based fuels like oil, causing the market to recognize the price of these negative externalities.

They recognize that “the costs of reducing carbon emissions are not trivial” and the concomitant need for revenue-neutrality in carbon pricing:

It is essential, therefore, that any taxes on carbon emissions be accompanied by equal, pro-growth tax cuts. A carbon tax that isn’t accompanied by a reduction in other taxes is a nonstarter. Fiscal conservatives would gladly trade a carbon tax for a reduction in payroll or income taxes, but we can’t go along with an overall tax increase.

Inglis/Laffer directly address concerns that putting a price on carbon (whether through a carbon tax or cap-and-trade) would put Americans at a competitive disadvantage:

If China and India join the United States in attaching a price to carbon, their goods should come into this country without a carbon adjustment. But if they do not, every item they place on our shelves should be subject to the same carbon tax that we would place on our domestically produced goods, again offset by a revenue-neutral tax cut.

If World Trade Organization rules entitle members to an unwarranted exemption from such a carbon tax, then we should change them. Outliers should not be allowed to frustrate the decision-making of the countries that are trying to prevent the security and environmental train wrecks of this century.

Although other conservatives including George W. Bush speechwriter David Frum and the American Enterprise Institute’s Ken Green have made similar arguments, Inglis and Laffer are the two most prominent Republicans to publicly articulate such a clear pro-carbon tax position.

The same day as the Inglis/Laffer op-ed, conservative pundit Charles Krauthammer published his own strong endorsement of a gas tax. Though his Weekly Standard article, The Net-Zero Gas Tax – A Once-in-a-Generation Chance, begins by describing Americans’ “deep and understandable aversion to gasoline taxes,” Krauthammer quickly presents what he refers to as the “blindingly obvious” energy independence and other benefits of an increase in the federal gas tax, and proposes what he calls:

Something radically new. A net-zero gas tax. Not a freestanding gas tax but a swap that couples the tax with an equal payroll tax reduction. A two-part solution that yields the government no net increase in revenue and, more importantly — that is why this proposal is different from others — immediately renders the average gasoline consumer financially whole.

Krauthammer envisions the simultaneous enactment of a carbon tax and an offsetting reduction of payroll taxes, with the payroll tax reduction kicking in a week before the gas tax takes effect. He notes as a “nice detail” the fact that the payroll deduction would be “mildly progressive” and follows with a constructive analysis of some of the nitty-gritty details of implementing his net-zero gas tax.

Finally, Times columnist Thomas Friedman weighed in with yet another strong call for a gasoline and/or carbon tax in Win, Win, Win, Win, Win. Echoing the previous day’s Times editorial, Friedman states what should be obvious:

It makes no sense for Congress to pump $13.4 billion into bailing out Detroit — and demand that the auto companies use this cash to make more fuel-efficient cars — and then do nothing to shape consumer behavior with a gas tax so more Americans will want to buy those cars. As long as gas is cheap, people will go out and buy used S.U.V.’s and Hummers. (emphasis in original)

Friedman follows with a geopolitical argument very similar to that made by Inglis, Laffer and Krauthammer:

A gas tax reduces gasoline demand and keeps dollars in America, dries up funding for terrorists and reduces the clout of Iran and Russia at a time when Obama will be looking for greater leverage against petro-dictatorships. It reduces our current account deficit, which strengthens the dollar. It reduces U.S. carbon emissions driving climate change, which means more global respect for America. And it increases the incentives for U.S. innovation on clean cars and clean-tech.

The weekend explosion of support for carbon and/or gas taxing followed by just three weeks a similar confluence, also described here, in which Thomas Friedman called for a carbon tax, the Wall Street Journal stated its clear preference for a carbon tax over cap-and-trade and Ralph Nader and Toby Heaps made a compelling case for pricing carbon emissions via a tax rather than a trading scheme in a Wall Street Journal op-ed.

This convergence of opinion from Left and Right signals an extraordinary opportunity to obtain bipartisan support for a revenue-neutral carbon tax. As Congressman Inglis and Mr. Laffer conclude:

As president, Barack Obama, by working with conservatives as well as the members of his own party, can at once clean the air, create jobs and improve the national security of the United States — a triple play for the next American century.

Will the environmental community unite to actually help pass climate change legislation? That remains to be seen as environmental groups continue to be split between carbon tax and cap-and-trade camps. I’ve worked closely with some of the groups supporting cap-and-trade, have tremendous respect for them and know they understand how important it is to put a price on carbon and to make very large reductions in greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible. I know that some cap-and-trade supporters are genuinely convinced that a carbon tax is simply not possible politically. Will that change as bipartisan support grows for a revenue-neutral carbon tax?

It’s time to recognize that 2008’s conventional wisdom is wrong. If we join together in a bipartisan alliance, Congress can adopt and implement a carbon tax in 2009.

Photo: Valerio Schiavoni / Flickr.

NRDC Evolves from Cap-and-Trade to “Cap-and-Invest.” Keep going…

A special report for the Carbon Tax Center by James F. Handley

For almost four decades, the powerhouse Natural Resources Defense Council has stood as the green movement’s stronghold for regulation-based eco-solutions. It has fought for, and won, energy-efficiency standards for appliances, cars and buildings; renewable-energy quotas for electricity supply; and parts–per-million regulations on chemicals in water, air and food have been NRDC’s stock-in-trade. But not price-based mechanisms like gasoline taxes, congestion tolls and carbon emissions pricing.

It was striking, therefore, to read NRDC finance advisor Andy Stevenson come out swinging for carbon emissions pricing. In Why Putting a Price on Carbon is Fast Becoming an Economic Necessity, posted this week on NRDC’s Web site, Stevenson warns that tightening

credit markets threaten to strangle investment in alternative energy. His solution — “cap and invest”:

The cap forms a limit on the amount of CO2 that can be emitted in a given year. This declining limit is then broken up into permits… auctioned off to emitting entities, creating a… revenue stream of roughly $150 billion a year over several decades that can be used to help collateralize the loans needed to put America back to work and move us in the right direction…. [O]ver a trillion dollars in the early years of a "cap and invest" program… to help finance innovative energy solutions for our economy… giving the banks confidence to once again finance longer-term investments at reasonable interest rates. Investments that will pay dividends both in terms of their economics under a carbon cap, as well as for their ability to help reduce our greenhouse gas emissions profile.

Once sufficient capital has been deployed to jump-start emerging energy technologies, this program would then be transformed from a "cap and invest" program into a "cap and dividend" program that would rebate energy revenues back to the American people.

We like that last piece, “dividend… to the people.” Why not start there?

Stevenson’s article suggests that NRDC is moving up the ladder from Boxer-Lieberman-style cap-and-trade towards "the gold standard" of a revenue-neutral carbon tax. Could the Council be following the progression laid out in the Congressional Budget Office’s “Caps vs. Taxes”

Stevenson’s article suggests that NRDC is moving up the ladder from Boxer-Lieberman-style cap-and-trade towards "the gold standard" of a revenue-neutral carbon tax. Could the Council be following the progression laid out in the Congressional Budget Office’s “Caps vs. Taxes”

report, of steps to make cap-and-trade more effective (and more like a carbon tax)?

-

100% auction (drop all permit giveaways)

-

safety valves and price floors to dampen volatility

-

recycle revenue via dividend or tax-shift

-

regulate (or eliminate) traders.

NRDC’s proposed cap-and-trade includes 100% auction and a loose safety valve. With Stevenson’s call for eventual revenue recycling, the group is at least contemplating the first three of these steps.

Yet the NRDC-Stevenson "evolutionary" approach of moving to cap-and-dividend only after a long incubation in cap-and-invest is riddled with problems. For one thing, once traders and polluters owned permits they’d be invested in the system. They’d have to be bought out to take the next step up the ladder toward the "gold standard" of a straight carbon

tax. Moreover, "green energy" subsidies are addictive, even if (or especially when) they don’t reduce emissions. Subsidies for corn-based ethanol — which Sen. McCain denounced in the Sept. 26 presidential debate

—– are a case in point.

Furthermore, a dividend or tax shift seem essential to counteract the income impacts of any carbon pricing scheme, whether tax or cap. Without revenue distribution, carbon emissions pricing is a regressive tax. Yet under either a cap or a tax, carbon prices will have to rise substantially to meet the emission reduction targets NASA’s Jim Hansen and most other climate scientists warn are essential to prevent catastrophic climate instability. The current financial meltdown cries out for a dividend or a tax shift over a regressive tax increase, since consumers are already being bled dry.

But the case against cap-and-invest would be strong even in flush times. Our government is lousy at choosing technology winners, particularly this early in the technology race. Remember synfuels? Lieberman-Warner was loaded with subsidies for similar money holes like nukes, ethanol, and “clean coal.” Carbon auction or tax revenue diverted to "green energy" programs, even well-crafted ones, is unlikely to drive conservation and innovation nearly as well as the steeper price increase on fossil fuels that could be politically and economically sustained if a broadly distributed dividend or tax shift were coupled with a tax (or cap) on carbon fuel producers. That’s because we know our homes and businesses better

than the government. With the right price signals, we’ll be in a far better position than government-mediated program officers to make decisions about how to reduce our use of fossil fuels.

NRDC’s thinking is evolving. But cap-and-invest is still a regressive policy that won’t do much good up-front. And down the line, as the cap tightens and fossil fuel prices soar, it will become wildly unpopular. Stevenson is right to suggest revenue recycling to offset that pain, but why wait? Why not skip “cap-and-invest” and go straight for “tax-and-dividend.” Economists

ranging from Ken Green on the right, Bill Nordhaus in the center and Robert Shapiro on the left are all saying “go for the gold” – a revenue-neutral carbon tax. Keep climbing, NRDC!

Photo: Flickr / Charlie Brewer.

Carbon Revenue Recycling is Focus of Capitol Hill Briefing

Reported for the Carbon Tax Center by James F. Handley

[Ed. note — two days after the Capitol Hill briefing, on Thurs. Sept. 18, the House Ways and Means Committee heard testimony on optimal pricing of carbon emissions, including a forceful presentation from carbon tax advocate New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg; watch this space for CTC’s report.]

At least one Washington politician dares to say “tax” out loud — a carbon tax, no less.

Representative John Larson (D-Conn.) headlined a Capitol Hill panel discussion Tuesday and came out swinging for a revenue-neutral carbon tax. Larson, a member of the Democratic House leadership and the tax-writing Ways and Means Committee, called carbon taxing the most effective way to curb greenhouse gas emissions. Addressing a briefing organized by Clean Air – Cool Planet and the Energy and Environment Study Institute, the five-term Congressman invoked his constituents at Auggie & Ray’s Diner in East Hartford: “They know climate protection comes with a price tag — they want transparency up-front so they know what to expect and can plan ahead. And they want a fair, level playing field.”

Both a carbon tax or the auctioning of permits under a carbon cap-and-trade system would generate huge streams of revenue which would come under the jurisdiction of Ways and Means. The Committee has scheduled a hearing tomorrow, Sept. 18, on revenue recycling, and Larson will be on hand, presumably putting the spotlight on the American Energy Security Trust Fund Act he introduced in August 2007.

Speaking to an overflowing House banquet room, Larson, shown at right, called a carbon tax “simple, efficient, straightforward and effective” and said it will be a boon to the economy if the revenue is recycled to reduce or eliminate distortionary taxes. Following Larson, a politically diverse panel of economists — Robert Repetto, Robert Shapiro, Terry Dinan, and Ken Green — discussed ways to maximize the “double dividend” — benefits to climate and to the economy from recycling revenue from either a carbon tax or the auction proceeds of cap-and-trade.

Speaking to an overflowing House banquet room, Larson, shown at right, called a carbon tax “simple, efficient, straightforward and effective” and said it will be a boon to the economy if the revenue is recycled to reduce or eliminate distortionary taxes. Following Larson, a politically diverse panel of economists — Robert Repetto, Robert Shapiro, Terry Dinan, and Ken Green — discussed ways to maximize the “double dividend” — benefits to climate and to the economy from recycling revenue from either a carbon tax or the auction proceeds of cap-and-trade.

Several noted the most egregious flaws of the defeated Lieberman cap-and-trade bill: it would have given away emission permits and auction revenues, mainly to fossil fuel industries, rather than recycling auction revenues downstream to consumers. Panelists noted that energy firms pass their costs downstream to consumers — who will need assistance. Only Repetto, of the UN Foundation, preferred cap-and-trade over a carbon tax, but with either, he wants a tax-shift — auctioning all permits and dedicating revenues to reduce other taxes.

Shapiro, a former Undersecretary of Commerce, warned of the costs and instability from price volatility under cap-and-trade, citing the U.S. acid rain program whose permit prices slosh around as much as 80% and the similarly volatile EU climate program which has achieved zero net greenhouse gas reductions. The morning after a disastrously volatile day on Wall Street, Shapiro called volatility the enemy of rational planning and efficient economic decision-making. Shapiro advocates recycling 90% of carbon tax revenue with the remaining 10% dedicated to R&D on low-carbon alternatives.

Dinan, author of a series of weighty CBO studies on climate policy documenting the advantages of a carbon tax, suggested ways to move cap-and-trade closer in efficiency to a carbon tax, for example by adding safety valves to limit price volatility. She underscored the efficiency advantages of applying revenues to reduce distortionary taxes such as payroll taxes, vs. distributing revenues equally with pro rata dividends. But Dinan and the new RFF study caution that unlike a straight dividend approach, tax-shifting out of payroll taxes would be acutely regressive, mainly because many low-income people, including elderly and the unemployed, don’t pay payroll taxes and thus wouldn’t benefit from payroll tax reductions. In contrast, dividends would go to everyone, equally, thus benefiting a clear majority of less-well-off individuals and households.

Ken Green, AEI resident economist and scientist who has written extensively about the “double dividend” from reducing distortionary taxes with carbon revenues, is rare among conservatives for supporting strong medicine to combat climate change. Because our entire society and every activity in it is built around energy consumption, changing energy prices will have profound effects, he noted, some of which must be offset. Green warned that politicizing climate change legislation or otherwise attempting to favor some constituents over others will “torpedo” the serious effort that is needed. Cap-and-trade hides the truth that we must use prices to change consumption patterns, said Green, and it will breed cynicism and undermine public support for climate protection. The public needs to understand that although fossil fuel prices will rise, they will be “made whole” as a group.

During Q&A an audience member noted the consensus for a carbon tax but asked panelists how a tax would provide the certainty that is often touted as the chief advantage of cap-and-trade. Shapiro suggested that carbon tax levels may need to be adjusted periodically to assure that emissions targets are being met. Green contended that powerful incentives for cheating and market manipulation will render cap-and-trade’s emissions certainty largely illusory. He called cap-and-trade a government-mandated constraint on supply, likening it to OPEC’s mission to limit oil supply to support prices. Just as in OPEC, cap-and-trade will bring irresistible temptation to cheat by selling outside the system and will eventually destroy public confidence, Green said.

Photo courtesy of Clean Air – Cool Planet

5 years on, the Indian Point disaster is its shutdown

Indian Point nuclear power plant, on the east shore of the Hudson River, in northwest Westchester County, north of New York City. Units 2 and 3, shown in photo, were permanently shut at midnight on April 30, 2020 and April 30, 2021, respectively. A smaller, prototype reactor, Unit 1, operated from 1962 to 1974. Photo: Eric Harvey for the Peekskill Herald, published Sept 24, 2024.

Once upon a time, hearing “disaster” and “Indian Point” in the same sentence probably meant that the nuke plant had just spilled radiation into the Hudson. Or maybe a whistle-blower was postulating a credible meltdown scenario that could trigger a lengthy shutdown, ensuring the plant’s capacity average wouldn’t surpass 50% — the generating equivalent of a ballplayer batting .200.

But that was last-century. Now nukes are climate-friendly, thanks to atomic fission’s sidestepping fossil fuels’ heat-trapping carbon emissions. Not only that, at century’s end Indian Point vanquished its on-line reliability problems. Starting in 2001, it racked up year after year of chart-topping generating performance right up to the plant’s forced demise that commenced five years ago tonight.

From a climate standpoint, the true Indian Point disaster is the plant’s closure and dismantlement. Both reactors are now kaput, their reactor cores chopped up. Unsurprisingly, the effort to decarbonize the state power grid — New York’s lowest-hanging climate fruit — is in reverse. Emissions are mounting, and in New York City and other downstate areas formerly supplied by Indian Point, electricity is getting costlier and less dependable.

From a climate standpoint, the true Indian Point disaster is the plant’s closure and dismantlement. Both reactors are now kaput, their reactor cores chopped up. Unsurprisingly, the effort to decarbonize the state power grid — New York’s lowest-hanging climate fruit — is in reverse. Emissions are mounting, and in New York City and other downstate areas formerly supplied by Indian Point, electricity is getting costlier and less dependable.

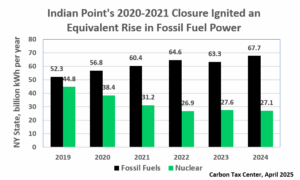

Turning off Indian Point has devastated electricity decarbonization in NY State

Rarely are opposing trends as clear as the two in the chart directly below. In the five years from 2019, just before Indian Point’s closure began, the amount of electricity made by burning fossil fuels in New York State grew in tandem with the drop in nuclear generation caused by Indian Point’s absence.

Over that 5-year term, as electricity generated statewide with nuclear power fell by 17.7 TWh, electricity generated with fossil fuels (essentially fracked methane gas) rose by 15.4 TWh a year. (A TWh, or terawatt-hour (TWh), equals a billion kWh’s.)

Chart by writer, from NYISO data extracted by Isuru Seneviratne. More details in paragraph directly below.

The loss of generation from Indian Point — 16 to 17 TWh a year, based on the 2001-2019 average — was supposed to be made up with “renewables.” Shutdown proponents, led by the advocacy group Riverkeeper, practically guaranteed it. A press release that the group issued as the hours counted down on April 30, 2020 was titled Indian Point 2 shuts down; NY’s renewable energy transition, for example. (Connoisseurs of the legendary “Dewey Defeats Truman” headline should flock to that Riverkeeper web page.) Yet increases in renewables can barely be detected in 2019-2024 statewide generation changes.

Over those five years, electricity produced statewide from wind, solar and burning forest products did grow by a healthy 70 percent. But because the starting base was small, the increase in absolute terms was a modest 6.2 TWh. Hydro-electricity, moreover, fell by 2.3 TWh, cutting the net 2019-2024 boost from renewables to a measly 3.9 terawatt-hours. Virtually the entire slack from shutting Indian Point had to be taken up by increased burning of fossil fuels — not because of gas greedheads but because no other power source was available. (The various 2019-2024 generation changes meticulously compiled by the NY Independent System Operator have been distilled into a comprehensive chart created by Isuru Seneviratne, who monitors state electricity data for the advocacy group Nuclear NY.)

Renewables won’t soon make up Indian Point’s lost output

Renewable-power sources being developed for NY State can be placed in three groups.

- 1,200 megawatts (MW) of new hydroelectric power being brought to NY State from Quebec via a new 339-mile long transmission line known as the Champlain Hudson Power Express (CHPE).

- Wind farms in the Atlantic Ocean off Long Island, beginning with the 2,070-MW Empire Wind 1 and 2 arrays south of Long Beach (my hometown).

- New utility-scale on-shore wind and solar in various stages of permitting and construction, comprising nearly 50 ventures totaling around 7,000 MW.

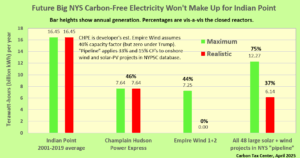

Empire Wind generation is zeroed out in “realistic” scenario due to Trump’s fear and loathing of offshore wind. Realistic scenario for solar and (onshore) wind in project pipeline assumes one-half of maximum generation.

The raw megawatt figures above may appear imposing, but less so when we account for three crucial factors:

(i) Only CHPE can provide reasonably consistent electricity, with a capacity factor between 70% and 75%; the wind and solar farms are weather- and astronomically-limited to much lower annual outputs: I posit 40% (offshore wind), 33% (onshore wind) and 15% (solar).

(ii) Offshore wind is almost certainly dead in the water (sorry!), due to the U.S. president’s implacable hatred (rooted in his belief that a nearby wind-power venture would threaten the profitability of one of his Scotland golf courses). [See addendum at end of this post.]

(iii) Not all projects in the state renewables “pipeline” will prevail through permitting obstacles, local opposition and financing problems.

The bar chart at right adjusts for these factors by presenting the prospective the three categories of new carbon-free electricity alongside Indian Point in annual terawatt-hours. The green bars sum to 27 TWh, indicating total new carbon-free generation nearly two-thirds greater than that lost when the nuke plant was taken away. The more-realistic red bar sum, 13.8 TWh, is only around half of the maximum, and is less (by 14%) than Indian Point’s lost contribution.

Let’s also face that having new renewables make up for the generation lost by closing Indian Point is a pathetically low bar. New wind and solar were supposed to contribute mightily to stopping climate change by pushing fossil fuels out of the grid . . . which they cannot do at present if their output must stand in for the carbon-free output that Indian Point was prevented from providing after 2020.

Lessons learned?

The outlook for decarbonizing the NY State power grid is grim, even if there’s a post-Trump world in which the U.S. government doesn’t throttle offshore wind as it has tried (unsuccessfully, thank goodness) to scuttle New York’s congestion pricing program. As the last bar chart shows, even bringing Empire Wind to fruition won’t make up half of Indian Point’s lost carbon-free output.

And this post hasn’t touched on the closure’s prospective toll on downstate electricity rates and reliability. Nor has it treated the possibility that deteriorating U.S.-Canada relations will put a crimp in (or surcharges on) hydro-electricity from CHPE whose expected commencement next year is the only bright spot on the horizon, so far as large projects are concerned. (Rooftop solar has gained a solid foothold in New York State, which ranks third in the U.S. in the number of homes with solar panels, according to Solar Insure. Yet making up for Indian Point’s lost carbon-free output would require roughly one million new solar homes in the state — a 5-fold addition to the 200,000 existing solar homes in the state at the end of 2024.)

Here are three lessons learned from the premature closure of Indian Point:

Lesson #1. A robust carbon tax might have saved Indian Point. Based on its average 2001-2019 electricity output, a tax of $100 per ton of emitted CO2 would have conferred an annual carbon-avoidance value of three-quarters of a billion dollars on the Indian Point plant. (Calculation: 16.5 TWh/year x 10^9 kWh/TWh x 0.9 lb of CO2/kWh (per EIA, reduced slightly from that source’s 0.96 lb average to weed out peaker plants) x 1/2000 tons per lb x $100/ton.) A monetary bounty of that magnitude would have made it more difficult for Riverkeeper and then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo to engineer Indian Point’s closure. (During the decade preceding closure, the actual price under the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) to emit a ton of CO2 averaged 20 times less: around $5/ton.)

Lesson #2. Self-appointed environmental-interest groups should not be the primary arbiter of the public interest in climate-critical matters. “Climate was not at the table when Indian Point’s fate was being sealed,” I wrote in May 2020, weeks after Indian Point began to be shut down. Riverkeeper was at the table, of course, supported by several other prominent environmental organizations whose institutional biases led them, in my view, to overestimate the real-world availability of wind and solar electricity, undervalue Indian Point’s carbon-free benefit, and over-emphasize the risks of the nuclear plant’s continued operation. The result was that the “climate consequences of shutting Indian Point [were] brushed aside,” as suggested in the subhead to my 2020 post.

Lesson #3: New Yorkers must consider adding more nuclear power capacity to the state grid. I’m starting to re-evaluate the proposition that New York State can achieve a zero-emissions electric grid without adding considerable nuclear power capacity. This widely held viewpoint (“article of faith” might be a more apt term) was critiqued in late 2023 by PhD physicist and policy analyst Leonard Rodberg, whose analytical acumen and probity I’ve admired since the 1970s, when we were colleagues in the safe energy movement, as it was then called. Len’s detailed analysis concluded that approximately 29 GW of new nuclear capacity — the equivalent of 15 Indian Point plants — will be required in addition to large amounts of offshore wind as well as solar and other “distributed” power — to reliably and affordably decarbonize the state grid by 2040 while satisfying load growth from electrifying much of the space heating and vehicular transportation now provided by combusting fossil fuels.

Addendum

Heatmap and other news outlets reported on May 20 that the U.S. Interior Department lifted its April 16 stop-work order indefinitely halting construction of the 810-MW Empire Wind 1 in the Atlantic Ocean south of Nassau County, NY. This hopeful development is tempered, however, not just by the Trump administration’s notorious fickleness but by the fact that if and when completed the 810-MW wind farm will offset only a sixth of the carbon benefit that was destroyed by Gov. Andrew Cuomo and Riverkeeper’s closure of Indian Point. See graph.

A Lesson for NYC Congestion Pricing Came Last Week from Washington State

This post is adaped from my essay yesterday on Streetsblog USA, A Lesson for NYC’s Congestion Pricing Came Last Week from Washington State. It was posted on the eve of NY Gov. Kathy Hochul’s announcement today that she has ended her June “pause” and authorized New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority to begin implementing a scaled-down but still-robust version of the original plan, beginning at midnight January 5, 2025.

The Streetsblog post was intended to steel Hochul’s courage and, as we congestion pricing advocates have demanded since June, to prod her to “flip the switch” on the Manhattan toll scheme that was set to go into effect on June 30. It was actually written last weekend with the hope of placing it in the New York Times, but they could not fulfill our request for rapid publication. No matter, the governor’s turnaround was already in the works.

The post takes a few liberties with actual events in Washington, eliding the differences between the straight-up carbon tax measure that voters rejected in 2016 and the cap-and-trade measure that also failed at the ballot in 2018, and the state’s Climate Commitment Act that was enacted into law in 2021 and backed by voters last week. This was in service of the larger point: that the conception of what is fair changes when an effective policy has been given time to work, and that if a policy is wise, politicians should stay the course, confident that public support will emerge.

We’ll have more to say in the coming weeks about the pending rollout of New York’s congestion pricing plan, arguably the first-ever large-scale application of externality pricing in the U.S.

— C.K., Nov. 14.

The first time Donald Trump was elected president, in 2016, Washington State residents also voted down an initiative that would have created the country’s first statewide carbon tax.

The second time Trump won the presidency, last week, Washington residents flipped their 2016 stance on carbon pricing, voting to preserve the comprehensive carbon pricing program that their legislature ended up enacting. And therein lies a message for New York Gov. Kathy Hochul, who paused New York City’s Central Business District toll plan on June 5, just as it was about to go into effect after years of debate.

The message: If the policy is wise, stay the course. The facts on the ground will soon change, generating the political support to validate your policy and prepare you for the next policy battle.

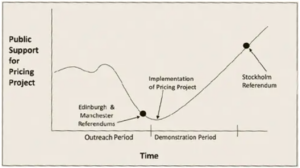

The famous chart of why politicians should stay the course when a policy is good, but unpopular.

Congestion pricing proponents have always known the odds. Taxes are unpopular, check. Driving is a birthright and change is hard, check. We were aware congestion pricing in London and Stockholm had only 40 percent favorability before adoption. But both cities’ experience showed that once traffic visibly lessened and transit improvements got underway, opinion flipped. Roughly 60 percent of residents now support the tolls.

The 2016 vote against Washington carbon pricing was a landslide: 59.3 percent no to 40.7 percent yes. The 2024 vote to keep the state’s carbon pricing law was a landslide in the opposite direction: 62 percent to keep it and 38 to repeal it. Hmm, looks like that 60-40 rule has legs!

A brief look at the law that Washington State voted to keep last week will demonstrate how it’s cut from the same cloth as New York’s congestion pricing.

Washington’s innovative Climate Commitment Act requires fossil fuel companies to buy permits keyed to the carbon content of their fuels. That includes oil refineries, which pass on the costs of the permits to motorists and homeowners as higher prices for gasoline and heating fuels.

The intent is to motivate industry and consumers to curb their carbon dependence, much like congestion pricing in New York would impel motorists to drive less often into gridlocked Manhattan. Sales of the emission permits in Washington are already helping finance electrification and renewable-energy substitutes for fossil fuels, just as New York’s congestion revenues would have bankrolled $15 billion in better transit.

And just as it has been in New York, the road to this decision wasn’t easy. Washington’s climate law took root after voters twice rejected ballot referendums for statewide pricing of carbon emissions by margins of around 60 to 40. (A 2018 initiative failed as well, 56.6 percent to 43.3percent.) But after Democrats won control of the legislature in 2020, Gov. Jay Inslee, a Democrat and unabashed climate champion, pushed through the Climate Commitment Act, much as New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo in 2019 won legislation directing the regional transit authority to institute a congestion pricing system.

This year, however, fossil fuel backers in Washington collected enough signatures to place Initiative 2117on the Nov. 5 ballot. A “yes” vote would have repealed the legislation and discarded the emission permits — perhaps slowing energy price increases but stalling the state’s shift toward clean power.

Well, the returns are in, and supporters of the emissions permit scheme won big.

True, what was on the ballot in Washington last week — making gasoline and other fossil fuels more costly to elevate lower-emission substitutes from smaller cars to electric cars and, best of all, less driving — isn’t the same as congestion pricing. But it’s a close cousin. What stands out is that a policy rejected by nearly 60 percent of voters in 2016 and again in 2018, won with around 60 percent in 2024. Attitudes can shift when facts warrant.

True, what was on the ballot in Washington last week — making gasoline and other fossil fuels more costly to elevate lower-emission substitutes from smaller cars to electric cars and, best of all, less driving — isn’t the same as congestion pricing. But it’s a close cousin. What stands out is that a policy rejected by nearly 60 percent of voters in 2016 and again in 2018, won with around 60 percent in 2024. Attitudes can shift when facts warrant.

What enabled the turnaround? A resolute governor stayed the course, allowing the “default” to recalibrate from cheap gas to clean power and letting the public warm to this novel policy for cutting carbon pollution. Once it did, 20 percent of voters came aboard, just like they did in London and Stockholm.

New York hasn’t been as fortunate yet. This spring, our executive gazed at the pending $15 peak congestion toll and rather than seeing less gridlock and a transformed transit system, saw a political abyss. Advocates and even her own staff tried to brace her for this “valley of political death” between congestion pricing’s initiation and its eventual acceptance. The warnings did no good. On June 5, she placed the tolls on “indefinite pause.”

There is talk that the governor will soon un-pause the tolls now that the suburban House races she feared would be swept up in a congestion pricing backlash are decided. But Gov. Hochul must move with urgency. The incoming president has made his distaste for the tolls abundantly clear. His return to power is less than 10 weeks away, with at least four of those weeks likely gobbled up by red tape. The plan’s logic that Hochul herself once articulated so well remains intact: better commutes and healthier, safer streets.

Hochul must act fast and trust the message from Washington State: with strong leadership, good policy and good politics can be one and the same.

Another venue ripe for cost internalization: NYC food delivery

This post was published earlier today by the New York livable-streets site Streetsblog, under the headline Reining in Deliverista Distances is the Key to Safety. I’ve cross-posted it here because the proposal it conveys — a per-mile charge on app-based food deliveries — is an easily understandable illustration of the principle of “cost internalization” embodied by carbon taxing. Other recent illustrations are Strawberry Yields Forever, which reported on a grower-backed tax on groundwater in California’s Pajaro Valley; A Tantalizing New Front in Externality Pricing, about a proposed tax on helicopter noise; and periodic posts on the twists and turns in the long campaign to implement congestion pricing in New York City (here and here).

The text here duplicates the expositon in Streetsblog but near the end adds a paragraph contesting the widespread presumption that externality pricing necessarily injures marginalized groups (environmental justice communities, in the case of carbon pricing; food-delivery riders, in the case of the mileage charge outlined here).

— C.K., Nov 5, 2024.

Food deliveries in New York are spanning ever-longer distances. Before food apps, and before motorized bikes, deliveries came from nearby — from the local pizza parlor or neighborhood joint. Now deliveristas can be seen traversing the East River bridges or blasting up the Hudson River Greenway and the Central Park drives. When I ask a delivery rider at a red light how far he’s going, it’s often much more than a mile.

I’ll say it out loud: All that DMT — Deliverista Miles Traveled — has become a drag on other city cycling. It’s made the streets more chaotic and is stressing our bicycle lanes. Routine cycling maneuvers like sliding over in the bike lane or turning now require constant signaling and checking to avoid getting clocked from behind.

Photo: Josh Katz. Photo montage: Streetsblog.

Cars and trucks remain the greater danger, of course. But I find lumbering vehicles easier to anticipate and navigate around than darting mopeds or e-bikes. No, I’m not giving up cycling, but I’ve lost count of how many acquaintances have. The need for vigilance and the fear of being taken down in a crash became too great.

What the Comptroller Missed

City Comptroller Brad Lander last week issued a report, Strategic Plan for Street Safety in the Era of Micromobility, aimed at safeguarding workers and minimizing dangers to the public from the food-delivery industry.

As Streetsblog reported, Lander wants the city to exert authority over app companies like DoorDash and Uber Eats that process 90 percent or more of food deliveries in the five boroughs.

His suite of reforms is a start, especially jawboning officials to throttle the import and use of non-UL e-bike batteries like the ones that have sparked scores of serious fires.

But it misfires in pinning its street-safety aspirations on an empowered workforce and a semblance of enforcement by NYPD. The first can only go so far. The second appears to be a pipe dream. Lander also failed to include the lowest-hanging fruit for food-delivery safety: reining in deliverista miles traveled.

Reduce ‘Deliverista Miles Traveled’

Picture 40 percent of citywide food-delivery e-bike and moped miles eliminated. This would greatly enhance everyone’s safety, not just by directly cutting the sheer amount of fast and sometimes startling two-wheeling but also by dialing down street chaos and helping other cycling regain a footing in bike lanes and general traffic.

So how would that be accomplished? Mathematically, by shaving a mile from current deliveries covering a mile or more

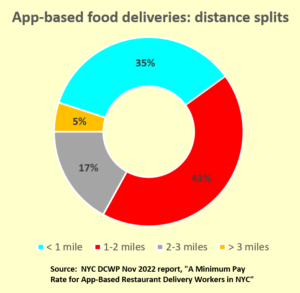

According to a 2022 report from the Department of Consumer and Worker Protection, nearly two-thirds of the city’s app-based food-deliveries exceed one mile. (And nearly one-quarter of all deliveries extend for two miles or more.) Trimming a mile from those deliveries would reduce average delivery distances to 0.85 miles from the current 1.50 — a 43-percent reduction that I round down to 40 percent.

Nearly two-thirds of app-based food deliveries in New York City cover more than one mile, according to city data.

How can we make this shrinkage come about? By taxing app-based food deliveries for each mile beyond an initial free mile — as I outlined over a year-and-a-half ago in the Streetsblog piece, “Want Safe Batteries? Stop Pretending Food Delivery is Free.” The dollar-per-extra-mile fee would be doubled in Manhattan south of 60th Street, where food choices are abundant and foot traffic and road congestion are heaviest. The charges would be paid to the city by the app companies, who would tack it on the bill — creating an incentive for customers to order from eateries closer to home.

I can’t say conclusively that my dollar charge will bring about the envisioned 40-percent mileage reduction. I can confidently predict traffic reduction from congestion pricing because there is so much data about car trips, but food-delivery mileage charging is uncharted territory. The dollar charge for deliveries over a mile might have to be higher, or perhaps could be lower, but we’ll only know if the city conducts surveys or a simulation with randomly selected families spending down pre-filled accounts.

What I can say with confidence is that the delivery mileage charge would generate a ton of revenue — perhaps not my earlier estimated $100 million a year, but close to it. This pot could pay to swap out unsafe batteries and establish deliverista hubs. Some of these endeavors are already under way, happily, and the Comptroller’s plan would move things along, though on the taxpayer’s dime.

(Don’t) Walk on the Demand Side

The omission of a delivery-mileage charge from Lander’s report is a huge missed opportunity, but it wasn’t surprising. New York City’s leading cycling advocacy group, Transportation Alternatives, has yet to mention the idea in its policy papers. Perhaps in striving for solidarity with deliveristas, TA has short-shrifted the concerns of non-commercial cyclists — as Michele Herman, lead author of TA’s classic Bicycle Blueprint (PDF), argued this year in the Village Sun.

Lander’s omission also mirrors the tendency in environmentalist circles to turn a blind eye to the consumption aspect of so many policy questions. Climate protesters picket at banks that they say enable drilling and pipelines, but not at the gas stations at which motorists dutifully fill Big Oil’s coffers or at showrooms pimping the machines that actually combust the petrol. Similarly, the decade-long project to divest pension funds and universities from fossil fuels didn’t cut carbon extraction and burning one iota. It did, however, divert “YIMBY” activism that is vital to New York and other inherently low-carbon cities.

Climate may seem gargantuan vis-a-vis food delivery, but the parallels are powerful. Both spheres treat “demand” as inviolate. Just as suburban households are allowed McMansions and fleets of SUVs, we city dwellers are unquestioned on our right to order meals and treats anytime from anywhere.

Externality pricing is sidelined in both spheres as well. Just as carbon taxes would crush demand for coal, oil and gas, a dinner-delivery mileage charge would help rebalance ordering from faraway to nearby, adding a measure of predictability and orderliness — hence, safety — to city streets, far more than policing could ever do. Yet internalizing even a sliver of an activity’s harms into its price is out of bounds in contemporary discourse. Congestion pricing, whose supposedly “too high” $15 toll would have only offset one-sixth of a car trip’s congestion causation cost, got shelved lest drivers flip out.

And let’s not overlook the diktat granting veto power to potentially afflicted outgroups. In carbon pricing, those are primarily environmental justice communities deemed threatened by carbon emissions charging, even though economic mitigations are readily available and EJ communities suffer the greatest damage from extreme heat, flooding and other climate-wrought disasters.

Delivery-mileage pricing would directly affect the city’s 65,000 deliveristas, of course, but perhaps not adversely. Diminishing deliverista miles traveled wouldn’t equally diminish their employment and wages, since total deliveries would be largely unchanged. What would almost certainly fall is the terrible annual toll of a dozen or more fatal on-the-job crashes.

No sector of labor (or business) in New York City should be held sacrosanct. All should be governed for the greater good. Food delivery regulation should advance social safety without infringing on worker power. A mileage fee on food deliveries can serve workers as well as the society of which they’re a part. What are we waiting for?

What Are EVs Good For?

This essay also appeared today in Streetsblog USA. The version here adds a table and line graph and a few explanatory words.

U.S. electric vehicles are only slightly less harmful to the environment and society than conventional gasoline cars, according to a new in-depth analysis by researchers at Duke, Stanford, U-C Berkeley and the University of Chicago.

This surprising finding — a mere 10 percent difference between electric and gasoline vehicles’ lifetime externality costs — emerges from a detailed “working paper” that the team of researchers posted earlier this month to the prestigious National Bureau of Economic Research.

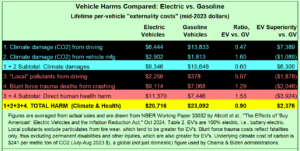

The paper, The Effects of ‘Buy American’: Electric Vehicles and the Inflation Reduction Act, includes the first attempt in a decade or more to monetize and aggregate automobiles’ primary direct harms: climate damage from manufacture as well as driving, along with crash deaths and non-climate pollution. EVs perform worse than GVs (gasoline vehicles) on three of these scores, according to the paper. Only on climate-damaging carbon emissions from driving do electrics triumph decisively over gasoline cars.

The paper, The Effects of ‘Buy American’: Electric Vehicles and the Inflation Reduction Act, includes the first attempt in a decade or more to monetize and aggregate automobiles’ primary direct harms: climate damage from manufacture as well as driving, along with crash deaths and non-climate pollution. EVs perform worse than GVs (gasoline vehicles) on three of these scores, according to the paper. Only on climate-damaging carbon emissions from driving do electrics triumph decisively over gasoline cars.

What’s keeping EVs from slam-dunk superiority over GVs? In a word, batteries. The batteries required to keep an electric vehicle moving make car manufacture far more energy-intensive for EVs than GVs, while their increment to vehicle weight — half-a-ton for a small EV, a ton or more for a standard large — renders EVs deadlier in crashes.

None of this comes as news to regular Streetsblog readers or aficionados of “car bloat” arch-foe journalist David Zipper. The new wrinkle in the NBER paper is its extensive monetization of harms. The paper suggests that the combination of EVs’ excess manufacturing energy and extra weight-caused fatalities undoes a third to a half of electric vehicles’ societal benefit from their lesser carbon emissions from driving. (See graph above.)

There’s more. Putting aside CO2 and climate, the NBER paper rates electric cars as worse polluters than gasoline cars when electrics’ associated smokestack emissions are properly counted. Yes, you read that right: the paper finds that particulate and gaseous emissions resulting from EV battery recharging are more harmful to health and the environment than gasoline cars’ tailpipe emissions — contrary to widespread faith in electric cars as an urban pollution solution.

Incremental vs. Average Emissions

Making sense of that finding starts with grasping that emission controls and cleaner gasoline — mandated by federal regulations that the auto and oil industry fought every step of the way — have slashed pollution from conventional autos compared to their 20th century precursors. I remarked on this enormous if underappreciated change in my tribute on Streetsblog to Brian Ketcham, the protean automotive engineer who died in August.

Data in table were used to derive bar chart, above.

Moreover, most U.S. power grids remain majority-carbon, notwithstanding wind and solar power’s rapid expansion. This means that plugging in an EV for recharging rarely summons additional power from non-carbon-based renewables or nuclear plants, since these are already running at their maximum capability. Rather, EV recharging anywhere in the 50 states tends to trigger increased output by gas- or coal-fired generators, especially the latter, which these days function as many grids’ swing generation.

The NBER authors’ pollution accounting meticulously (and correctly) assign those power plants’ incremental carbon and particulate emissions to the EVs. (Use of grid averages — the “default” in popular EV-climate discourse — isn’t just lazy, it greenwashes electric vehicles by crediting them with carbon-free electrons that should be allocated to pre-existing electricity usages.)

Despite my comfort with “incremental” rather than “average” pollution accounting — the approach I practiced in my long-ago career analyzing the U.S. power sector — I was still taken aback by the NBER researchers’ finding that EVs’ smokestack particulates and gases outweigh gasoline vehicles’ tailpipe harms by 6-to-1. But even dropping these “local damages” from the comparison, the other three harm categories combined give EVs only a 20 percent win vis-a-vis GVs. While that advantage ain’t beanbag, it’s a far cry from the prevailing conception of EVs as “green.”

It’s also a stark reminder of automobile dependence’s social unsustainability. Like it or not, the fact is that electric vehicles, though endlessly touted as benign, impose immense harms. And the NBER cost figures exclude the tens of thousands of permanently disabling car injuries each year (they only include fatalities), the health and ecosystem damage from the heavier EVs’ extra tire wear, and car culture’s budget-busting, soul-breaking impacts on Americans.

Also bear this in mind: The climate costs in the graph at the top of this post were calculated with a fairly aggressive “social cost of carbon” of close to $250. While the true cost of each metric ton of CO2 emitted today is probably higher — think of Hurricanes Helene and Milton, and the coming fallout from skyrocketing or unavailable home insurance, for starters — no country in the world actually prices (i.e., taxes) its carbon emissions at even half that rate. Using cost figures in the NBER paper, I’ve calculated that at any social cost of carbon below $150, the average EV is more harmful societally than the average gas vehicle.

That EVs improve only modestly on GVs under reasonably broad social accounting is sobering. Yes, their climate benefit is substantial, around 1.7 to 1 (throwing in manufacturing CO2 with driving CO2). But that ratio is miles away from a clean sweep. And with NIMBYs, NEPA and other obstacles to a truly green grid, it’s not going to rise very much for a while.

That EVs improve only modestly on GVs under reasonably broad social accounting is sobering. Yes, their climate benefit is substantial, around 1.7 to 1 (throwing in manufacturing CO2 with driving CO2). But that ratio is miles away from a clean sweep. And with NIMBYs, NEPA and other obstacles to a truly green grid, it’s not going to rise very much for a while.

A caveat: cataloguing and estimating automobile externalities, while a feature of the NBER paper, wasn’t its focus, which was to evaluate the generous subsidies to EVs (and their batteries) in the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. The paper itself is technical and laced with jargon and I may not have grasped every nuance.

That said, here are the NBER paper’s key bottom lines on car harms, as I understand them:

- Based on current U.S. electric grids, and including vehicle manufacture along with driving, EVs are 40 percent less climate-polluting on average than gasoline vehicles (GVs).

- Adding in the costs of car crash deaths to the above climate (carbon) pollution costs, EVs in the U.S. are 19 percent less societally harmful than GVs, on average.

- Also adding “local” tailpipe and smokestack pollutants to the calculation in #2, EVs are only 10 percent less societally harmful than GVs.

- Finding #3 rests on figures in the NBER paper indicating that smokestack pollution from EV charging causes six times as much health and other harms as GV tailpipe pollution — a finding that warrants close vetting. (The NBER authors directed me to their model results but refused my entreaties for a more convincing explanation of that finding.)

- Results 1-3 omit non-fatal crash injuries (an omission favoring EVs), particulates from tire wear (also favoring EVs), geopolitical entanglements from oil dependence (an omission favoring GVs), noise pollution, and other physical and societal maladies from automobile dependence.

- Even with those omissions, the lifetime unpriced costs from both types of vehicles average more than $20,000, a figure that would tack on 40 percent or more to today’s average U.S. $48,000 purchase price of new automobiles.