Ontario Greens Advocate B.C.-style Carbon Tax (Canoe)

Search Results for: british columbia

The carbon tax is working nicely

British Columbia’s Carbon Tax is Working Nicely (Sydney Morning Herald)

BC Carbon Tax Goes Up

British Columbia Carbon Tax Ticks Up, Remains Popular (Global BC)

The Carbon Tax Revenue Menu

Getting the politics to align for a carbon tax requires the right blend of honey and vinegar. For years, advocates’ and opponents’ attention alike has focused on the vinegar – the tax part. Lately, though, we’ve noticed growing interest about how to best spread the honey — the potentially huge revenues a carbon tax would generate. Here’s a primer on the options: what they are, how they would work, their merits and drawbacks, and who’s pushing them hardest.

Setting the initial tax rate at $15/T CO2 and increasing it by that amount each year (reflecting the maximum carbon tax rate and ramp-up of Rep. Larson’s bill) we estimate that the Treasury would take in approximately $80 billion in revenue in the first year. (This calculation uses the Carbon Tax Center’s spreadsheet model.) This amount would rise each year, though at slightly less than a linear rate as carbon reductions kicked in, reaching around $600 billion by the tenth year.

The allure of carbon tax revenue also offers a growing incentive for other nations to match a U.S. carbon tax in order to avoid WTO-sanctioned border tax adjustments, capturing the revenue themselves. Indeed, Brookings economist Adele Morris calls a carbon tax a “two-fer” because along with a growing revenue stream would come substantial CO2 emissions reductions. For the U.S., based on historic price-elasticities, CTC’s model projects a 30% reduction in climate-damaging CO2 emissions by the tenth year, compared to 2005 levels.

Six hundred billion (again, that’s the projected take in the tenth year from an ambitious carbon tax) is a lot of revenue, equivalent to around a quarter of federal tax receipts. As Ian Parry and Roberton Williams recently explained in “Moving U.S. Climate Policy Forward: Are Carbon Taxes the Only Good Alternative?” (Resources for the Future), the efficiency advantages of a carbon tax depend on using the revenue wisely. Not surprisingly, there are loads of claimants. Here’s a guide to the most prominent ones, sequenced more or less from the political left to right:

a) “Dividend.” Climate scientist James Hansen contends that to support a steadily-rising CO2 price, the public needs to see the money — every month. He calls his proposal “fee & dividend.” Senators Cantwell (D-WA) and Collins (R-ME) introduced the “CLEAR” bill which uses “price discovery” via a cap to set its carbon tax which would begin at a price between $7 and $21/T CO2, increasing 5.5% each year. CLEAR would return 75% of revenue via direct “dividends” and dedicate the remaining 25% to a fund for transition assistance and reduction of non-CO2 emissions. Rep. Chris Van Hollen (D-MD) also introduced a cap & dividend bill in the Ways & Means Committee. It relies on a cap to set the CO2 price indirectly, aiming for 85% reductions (over 2005 levels) by 2050. Because of its similar emissions trajectory, we’d expect Van Hollen’s bill to generate similar revenue to Rep. Larson’s bill: roughly $80 billion in the first year, rising to about $600 billion within a decade. Both the CLEAR bill and the Van Hollen bill bear the intellectual and organizing stamp of social entrepreneur Peter Barnes, who founded “Cap & Dividend,” and Peter’s allies including the Chesapeake Climate Action Network.

b) Payroll tax rebate. Rep. John Larson’s “America’s Energy Security Trust Fund Act” pairs a carbon tax with rebates of payroll taxes on earnings. As articulated by Tufts University economist Gilbert Metcalf (now serving at the Treasury Department’s energy office), Larson’s proposal has the appeal of broad fairness. It would distribute revenue very evenly across both income and regions. Because Rep. Larson’s approach rebates payroll taxes via a credit on federal income taxes — it would rebate the payroll tax on the first $3600 of income in the first year, with that threshold and rising over time — it avoids tangling with the Social Security Trust fund.

Economist and former Undersecretary of Commerce Rob Shapiro supports the approach of a payroll tax rebate, arguing that cutting payroll taxes could spur job growth. Social entrepreneur Bill Drayton, founder of “Get America Working,” is also a strong advocate of using carbon revenue to cut payroll taxes in order to stimulate employment while reducing emissions. Al Gore captured the idea with the phrase, “tax what we burn, not what we earn.” Former Rep. Bob Inglis (R-SC) introduced the “raise wages, cut carbon” bill co-sponsored by Rep. Jeff Flake (R-Az). Conservative economists Greg Mankiw and Douglas Holtz-Eakin, both of whom have advised Republican presidents and candidates, have also supported shifting tax burdens from payrolls to carbon emitters. And the Progressive Democrats of America endorsed the Larson bill.

c) Deficit reduction. Brookings economists including Ted Gayer and Adele Morris have been pointing out the potential for climate policy to reduce deficits. While deficit reduction isn’t revenue return in the immediate sense that Dr. Hansen suggests, Morris points out that deficit reduction will benefit future taxpayers by paying down at least part of the nation’s debt, rather than letting it continue accumulating interest. In this way, she suggests, the impulse to help future generations via foresighted climate policy would have a natural fiscal correlative of reducing future tax burdens.

Supporters of applying carbon tax revenues to deficit reduction include MIT’s Michael Greenstone (chair of the Brookings Hamilton Project on climate and energy policy) and Alice Rivlin, founding director of the Congressional Budget Office, who co-chaired the Bipartisan Policy Institute’s alternative to the Obama deficit commission. Prof. Metcalf proposed a carbon tax to the commission, with revenue return as “transition assistance” in the early years, shifting to deficit reduction in later years. As Irwin Stelzer of the conservative Hudson Institute recently pointed out, when the options to close budget gaps sift down to unpopular alternatives such as a value added tax (regressive and annoying, as EU residents will attest) or curbing home mortgage deductions, a carbon tax may emerge with greater appeal. While Keynesians argue that the present weak economy militates against any net increase in taxes, a phased-in allocation of carbon tax revenues to deficit reduction such as Prof. Metcalf proposes may circumvent that objection.

d) Income tax cuts. Greg Mankiw has suggested cutting income taxes as an alternative to payroll tax cuts to return carbon tax revenues; those Form 1040’s could include a carbon rebate drawn from those revenues for every taxpayer. Revenue could be returned via a lump sum credit (which would be income-progressive) or by reducing income tax rates (arguably more stimulative of income-earning activity).

e) Corporate income tax (CIT) rate cut. At a recent AEI event “Whither the Carbon Tax,” AEI economist Kevin Hassett argued for a carbon tax paired with a reduction in the corporate income tax rate. The Wyden-Coates tax reform bill proposes to reduce top CIT rates and make up the revenue by closing numerous exemptions, indicating interest on the Hill. Adherents of CIT rate cuts point to IMF studies saying that U.S. CIT rates are among the world’s highest, asserting that these taxes are especially stifling of business activity and employment. Hassett and his AEI collegue Aparna Mathur argue that CIT’s are passed through as higher prices for consumers and passed back to the factors of production: labor (in the form of reduced wages) and capital (in the form of reduced corporate earnings). They estimate that using carbon tax revenue to cut the effective CIT rate would result in return of about 40% of revenue to wage-earners, which they assert would give the CIT to carbon tax shift a net progressive effect. Their conclusion may be a stretch, given that real wages have remained stagnant or fallen for decades while corporate profits are rising briskly, but a CIT cut has strong salience for conservatives and business leaders.

f) The sampler platter. The options listed above can be mixed and matched. In fact, British Columbia’s carbon tax (which started at $10/t CO2 in 2008 and rises $5/t each year — it notches up to $25 per metric ton on July 1) launched with a distribution of a $100 direct “dividend” to each taxpayer even before the carbon tax was levied, and is now returning revenue via cuts in payroll, income and corporate tax rates. Former BC Premier Gordon Campbell was re-elected to a third term in 2009 after enacting the carbon tax with this mix of revenue return measures, perhaps indicating that a diverse approach to revenue return can have broad and sustained appeal.

Each of the revenue options has important economic and political advantages as well as disadvantages. At the June 1 AEI event, Kevin Hassett decried Senator Cantwell’s direct “dividend” as “terrible policy” because it foregoes the efficiency advantage of using carbon tax revenue to reduce or possibly eliminate other taxes that dampen economic activity. In 2007 Hassett and his AEI colleague Ken Green published an essay aguing for a carbon tax shift as a “no regrets” policy for conservatives, because its tax reform benefits would make it worthwhile even without climate benefits. They pointed to the work of Stanford’s Lawrence Goulder who concludes that the benefit of reducing other distortionary taxes can be large enough to offset some or all of the dampening effect of adding a carbon tax, a phenomenon known as a “double dividend.”

Still, the potential political attractiveness of direct distribution of revenue can hardly be overstated. Dr. Hansen is no politician and doesn’t claim to be an economist, but he sticks to the “dividend” or “green check” while noting that because of its clear and briskly rising price, Rep. Larson’s approach is nevertheless the best climate option on the table. Rep. Van Hollen, outgoing chair of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, certainly knows a thing or two about politics, and Senator Cantwell very effectively made the case for her “cap & dividend” approach last month at Brookings. But even she seems to be looking at other items on the revenue return menu. For the first time, she suggested appropriating some carbon revenue for deficit reduction, confirming that as high summer arrives in Washington, fiscal matters remain the topic for this Congress.

Photo: Flickr.

CANADA NEEDS TO BE LESS HYPOCRITICAL ABOUT ITS ROLE IN CLIMATE CHANGE

Canada Flouts Kyoto; British Columbia’s Carbon Tax Points To A Better Way (Calgary Beacon)

Should Carbon Pricing Advocates Support the Cap-and-Dividend Bill?

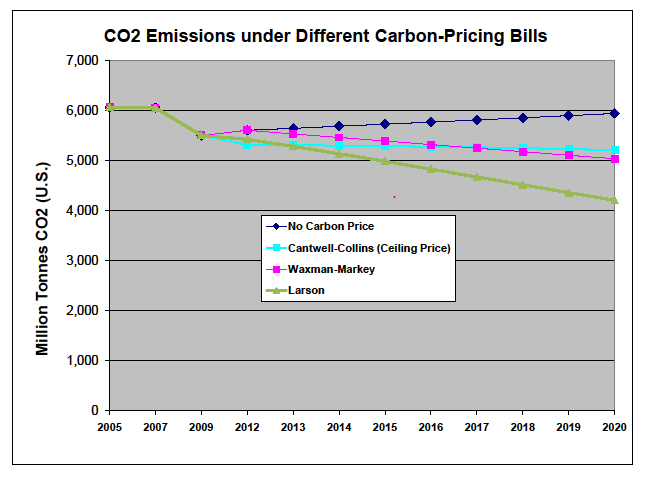

Last month’s Pricing Carbon Conference at Wesleyan U. featured a debate over three competing approaches for pricing carbon emissions, each of which is embodied in bills introduced in the 111th Congress:

- Cap-and-trade with offsets (essentially the Waxman-Markey bill);

- Cap-and-dividend (essentially the Cantwell-Collins bill); and

- A stepwise shift from payroll taxes to carbon taxes (essentially the Larson bill).

The Conference also offered a workshop comparing two ways to return revenues raised by a carbon tax or by selling carbon emission permits:

- a regular “dividend” or “green check” sent to all U.S. households; vs.

- a series of periodic reductions in payroll taxes.

Cap-and-Dividend proponent Peter Barnes, flanked by NRDC's Dan Lashof (left) and Carbon Tax Center's Charles Komanoff (right), at the Wesleyan Pricing Carbon conference.

As hoped, the Conference has sparked a flurry of substantive and strategic discussions. For example, cap-and-dividend advocate Peter Barnes is imploring us to align the Carbon Tax Center with the CLEAR cap-and-dividend bill introduced in December 2009 by Senators Cantwell (D-WA) and Collins (R-ME).

The CLEAR bill is backed by a coalition of largely grassroots organizations, who view it as a way to achieve a guaranteed reduction in emissions without the political compromises and anti-consumer aspect of cap-and-trade with offsets. We hold Peter and his coalition partners in high regard. Their cap-and-dividend concept is certainly a quantum improvement over the cap/trade/offset model that some of the mainstream environmental groups rode to defeat (again) in 2009-2010. Yet both the concept and the particulars of the CLEAR bill fall far short of what we at CTC believe is required in carbon-pricing legislation.

In this post, we contrast the CLEAR bill with the approach taken by Rep. Larson (D-CT) and 12 co-sponsors in their carbon tax bill, America’s Energy Security Trust Fund Act, which Mr. Larson pledged at Wesleyan to re-introduce in the new Congress that convenes in January.

The CLEAR Bill at a Glance

Like all cap-based bills, the CLEAR bill relies on a declining “cap” in the number of carbon emission permits to be auctioned to emitters. In CLEAR’s case, the promised decline (relative to 2005 emissions) would be 20% in 2020, 30% in 2025, and so forth, finally reaching an 83% drop by 2050. CLEAR would return 75% of the revenues from the permit auctions to all U.S. residents, with each getting an identical amount. The remaining 25% of revenue would be placed in a “Clean Energy Reinvestment Trust Fund” (CERT) for appropriation by Congress, ostensibly to “green energy” investments, mitigation, adaptation and transition assistance.

As a brake on price volatility, and to provide a modicum of price predictability, CLEAR sets a floor and ceiling on the prices of the carbon emission permits: the floor is set at $7 per ton of CO2 rising at 6.5% annually plus the rate of general inflation, with the ceiling at $21/ton, rising at 5.5% plus inflation. The floor is intended to protect investments in low-carbon measures by ensuring that fossil fuel prices include at least a minimum charge for their carbon emissions, while the ceiling is intended to shield consumers from too-rapid price rises. When the ceiling is hit, a “safety valve” in the CLEAR bill triggers auctions of additional permits at the ceiling price; the revenue from these supplemental permits is added to the CERT fund.

CLEAR’s Biggest Problem: Its Cap Hides a Much-Too-Low Price

The Carbon Tax Center has modeled the price levels needed to achieve particular emissions reductions. Our conclusion, using historical energy price-elasticity data, is stark: the CLEAR bill’s emissions reductions targets cannot be achieved within the bill’s low price ceiling. When we conveyed this finding at a meeting with Sen. Cantwell’s staff in early 2010, the response was even more stark: “We don’t intend to use (CO2) prices to reduce emissions.” — a statement that appears to deny the fundamental role of prices in driving changes in behavior.

The apparent disconnect between CLEAR’s emission targets and its price ceiling means that the ceiling price would be hit frequently, perhaps even continuously. This in turn would open the safety valve and cause the auctioning of supplemental emission permits, whose revenue would fund CERT. In effect, then, as the cap tightened, CLEAR would function like a low carbon tax (with the level set at the safety valve auction price), an increasing share of whose revenues would flow to the CERT fund. The initial promise of returning 75% of revenue would recede as the cap tightened and an increasing share of revenue went to the CERT fund. In this respect, CLEAR might even come to resemble the “Breakthrough” proposal for a low carbon tax to fund RD&D, albeit with less specificity about which technologies Congress might choose to subsidize and less clarity about the expected CO2 prices.

The apparent disconnect between CLEAR’s emission targets and its price ceiling means that the ceiling price would be hit frequently, perhaps even continuously. This in turn would open the safety valve and cause the auctioning of supplemental emission permits, whose revenue would fund CERT. In effect, then, as the cap tightened, CLEAR would function like a low carbon tax (with the level set at the safety valve auction price), an increasing share of whose revenues would flow to the CERT fund. The initial promise of returning 75% of revenue would recede as the cap tightened and an increasing share of revenue went to the CERT fund. In this respect, CLEAR might even come to resemble the “Breakthrough” proposal for a low carbon tax to fund RD&D, albeit with less specificity about which technologies Congress might choose to subsidize and less clarity about the expected CO2 prices.

The CERT Fund—Big Dogs Eat First, But Can They Reduce Emissions?

Needless to say, the same interests that wrote themselves free allowances under the Waxman bill would use their political muscle to divide up the CLEAR bill’s CERT fund. Thus, no one should be surprised if “clean coal,” ethanol and other “incumbent” energy interests garnered a lion’s share of the CERT fund’s supposed “clean energy investments.”

Nevertheless, CLEAR proponents appear to assume that the CERT fund would achieve near-miraculous reductions in carbon emissions. Our modeling indicates that because CLEAR’s price level is held so low, the bill would have to rely on the CERT fund to achieve more than half of its mandated 2009-2020 emissions reductions. Indeed, with its low (5.5%) annual increase rate, CLEAR’s $21 ceiling price would rise to only about $35 in a decade; that’s less than a third of the 2020 price in the Larson bill. No wonder Larson is projected to reduce emissions by 30% by harnessing the power of real price signals, whereas the CLEAR bill would have to rely on unspecified (and likely pork-laden) energy “investment” simply to achieve a reduction of 20%.

The Vast Costs of Hiding the Price

The main (political) appeal of a cap seems to be to hide the price. Yet hiding the price from investors and households guarantees that caps will be far less effective than direct pricing mechanisms at inducing investment in low-carbon energy and efficiency. The Brattle Group, a well-respected economics consultancy, studied the price volatility in the European Union’s Emissions Trading Scheme and concluded, first, that the noisy, hidden price signal there delayed investment in alternative energy by a decade; and, second, that the cap-derived CO2 price would have to rise roughly twice as high to get the same emissions reductions as an explicit tax.

Moreover, as we saw in the acrimonious and puerile debate over the Waxman bill, “hide the price” leaves everybody with an Internet link free to speculate on the cost of the legislation, with estimates ranging from astronomical (by those opposing action) to microscopic (by those claiming that “cost controls” such as offsets would avoid the need for significant CO2 prices). The result of “hide the price” in 2009-10 was a confused public and a stymied Congress. There’s no reason to expect a clearer discussion if cap systems continue to be the preferred way to price carbon emissions.

Hiding the price under a cap also complicates international harmonization. As we described in a post here in March 2009, and “Report from Copenhagen: Forget carbon targets, just set a price” an explicit carbon tax with border tax adjustments can be an effective incentive for other nations to enact their own carbon taxes to garner the tax revenue that their carbon-taxing trading partners will otherwise collect on imports at the border.

CLEAR’s Flimsy Wall Around Wall Street

The CLEAR bill seeks to avoid inducing speculative secondary markets by fiat: prohibiting entities that buy or sell emission permits from buying and selling carbon derivatives. It also would require CFTC, FERC and FTC to promulgate regulations on CO2 emissions trading. But as the Congressional Budget Office, Robert Shapiro and other economists have concluded: because of the energy industry’s need for insurance against wild price swings, the use of hedging instruments is unavoidable in the large and volatile CO2 markets that are inherent when setting a price indirectly using a cap. It appears inevitable that a secondary market would emerge overseas, if not illicitly onshore.

CLEAR’s Big Contribution: Revenue Return

The CLEAR bill did perform a great service by bringing revenue return via “dividends” into public discussion, at a time when Waxman-Markey proposed what amounted to a 40-year earmark of carbon revenues. (W-M would have allocated 85% of allowances, overwhelmingly to “incumbent” energy interests – effectively, a hidden, volatile and regressive tax.) CLEAR would at least start with 75% revenue return, although as discussed, that fraction would diminish as the cap tightened and the price ceiling was hit. Nevertheless, revenue return via a “dividend” or “green check” offers transparency and accountability that could help build political support for carbon emissions pricing.

On the other hand, returning revenue via reduced taxes on workers, as Rep. Larson proposes, would also avoid regressivity while offering the additional advantage of employment stimulus. This kind of tax-shifting seems to be a key ingredient in the continued political and economic success of the carbon tax in British Columbia and its effectiveness has been widely recognized here, too. Cutting payroll taxes has been praised by the Congressional Budget Office as one of the most cost-effective ways to reduce unemployment. The bipartisan “Hire Now” Act, co-sponsored by Senators Hatch and Schumer, effective in March 2010, eliminated the first six months of payroll taxes on employers that hire the unemployed.

While pro rata “dividends” offer appealing transparency and simplicity, the potential for a “job-creating carbon tax” to cut payroll taxes while de-carbonizing our economy seems no less attractive, particularly with officially-measured unemployment persisting above 10%. Though we conclude that CLEAR bill is too flawed to serve as effective carbon pricing legislation, it did at least jump-start the much-needed debate about revenue return. For that, Senators Cantwell and Collins and CLEAR’s supporters deserve high praise.

Photo: Wesleyan University

New Converts to Carbon Tax: Welcome Aboard, Now Start Rowing

(Note: NYT DotEarth blogger Andy Revkin linked to this post today in a piece that has more from Bill Gates on carbon pricing. Click here. – C.K., Sept 2.)

Last week, Bill Gates. This week, Bjorn Lomborg. With the world’s #1 software magnate and the man whom the Guardian labeled “the world’s most high-profile climate change skeptic” both endorsing a carbon tax, is the tide of influential opinion on climate policy and carbon pricing turning?

Yes and no.

Let’s look at Lomborg first. The Danish policy analyst built a lucrative career lambasting climate-change advocates as scaremongers who would consign millions to early death by devoting resources to decarbonizing the world economy rather than fighting killer diseases like malaria. But in a new book to be published next month, the self-styled “skeptical environmentalist” reportedly will call global warming “one of the chief concerns facing the world today” and “a challenge humanity must confront.” According to the Guardian, Lomborg will urge investing tens of billions of dollars a year to tackle climate change, with the funds to be raised through a carbon tax.

In somewhat overheated prose, the Guardian called Lomborg’s new-found resolve to combat global warming “an apparent U-turn that will give a huge boost to the embattled environmental lobby.”

Gates, on the other hand, has long worried about climate change. But in an interview in Technology Review last week, he added a new wrinkle: criticism of cap-and-trade:

TR: [A]lmost everyone agrees that there needs to be a price on carbon–whether a Pigovian tax or a cap-and-trade system. Without a price, there’s going be very little incentive to do the kinds of research, or create the kinds of technologies, or build out the kind of infrastructure, that we need.

Gates: No, that’s not right. It’s ideal to have a carbon tax, not just a price on carbon, which is this fuzzy term that includes cap-and-trade.

TR: Well, ideally, you’d do a Pigovian tax —

Gates: No, not a Pigovian tax. A Pigovian tax is where you pay for the damage. Here, you’re not paying for the damage — you can’t pay for the damage. You’re using the tax to create a mode shift to a different form of energy generation.

TR: That sounds very rational, pragmatically feasible, and humane. It also sounds politically unlikely.

Gates: Which is more likely: a [hidden] carbon tax [Gates’ way of describing cap-and-trade] with all sorts of markets and options and uncertainties about prices, and traders in the middle, and confusion about who initially gets the most advantage? Or a regulatory thing that says you mark every coal plant in the country with when it has to be retired, and a 2 percent tax to fund the R&D so that utilities know they can buy a plant that’s emitting hardly any CO2?

Gates’ disparagement of cap-and-trade is striking. But neither his 2% carbon tax nor Lomborg’s, which appears to resemble Gates’ in magnitude and function ─ funding energy R&D ─ is going to end the reign of fossil fuels in the foreseeable future.

The notion of an R&D solution is alluring. Who doesn’t want there to be global warming antidotes lurking in garages and labs, waiting for funding to unlock them? But it’s a chimera. Even with unlimited research funding, no technological breakthroughs can dislodge carbon-based fuels from dominion over the world’s energy economy. Fossil fuels’ energy density is too great, and their positional advantages of infrastructure and institutions too powerful.

Yes, subsidies can help push renewables past the “hump” in the S-curve to where scale economies can kick in and take a few bites out of the fossil fuel pie. But as New Republic blogger Brad Plumer pointed out recently, “Government subsidies just don’t pack the same punch as a market price on carbon pollution.” When a commodity or activity causes harm, the surest way to reduce it isn’t to subsidize a thousand and one alternatives but to directly discourage the thing by internalizing the cost of the harm into its price.

Ironically, Barack Obama appeared to grasp this during his run for the presidency. In a February 2008 interview with the San Antonio Express he enthused over the idea of a carbon tax:

Q. Have you considered … taxing emerging energy forms, for example, say a penny per kilowatt hour on wind energy?

A. Well, that’s clean energy, and we want to drive down the cost of that, not raise it. We need to give them subsidies so they can start developing that. What we ought to tax is dirty energy, like coal and, to a lesser extent, natural gas. (emphasis added)

How big a carbon tax is needed? A lot more than 2%. Raising electricity prices by 2%, if that’s what Gates envisions, would reduce electricity usage by an estimated 1.4% over the long run. Assuming, as modeling at the Carbon Tax Center suggests (xls), that fuel substitution (gas and nuclear for coal, wind and solar for gas, etc.) contributes roughly two units of carbon reduction for each unit gained from demand destruction, the total impact of the Gates tax on carbon emissions from the electricity sector would be just 4-5%. Since other sectors are less price-elastic, the average economy-wide reduction would be even less, probably just a few percent.

Contrast this with the bill introduced by Rep. John Larson (America’s Energy Security Trust Fund Act of 2009, H.R. 1337), which has a first-year carbon tax of $15 per ton of CO2 increasing steadily and predictably at $10-$15/ton each year, that would cut (xls) U.S. carbon emissions by approximately 30% by 2020, or an order of magnitude more than Gates-Lomborg carbon taxes. And Larson would return the vast bulk of carbon revenues to workers’ paychecks while setting aside a fund for the sort of clean energy R&D that Gates and Lomborg espouse.

Why the 10-fold difference in impact? A large carbon tax like Rep. Larson’s would create profound incentives: on the demand side to use less energy (via billions of decisions at household and social levels), and on the supply side to shift fuels and power to low- and zero-carbon sources (via thousands of decisions by entrepreneurs, utilities and energy companies). A mere 2% carbon tax, even one with revenues allocated to R&D, would not.

In his Technololgy Review interview, Gates at least coupled his carbon tax with a notion of ordering utilities to shut down CO2-intensive plants at such and such a time:

And then you just take all the carbon-emitting plants, you look at their lifetime, and you say on a certain date this one has to be shut down, and when a new one is put in place, it has to be low-CO2-emitting.

But how this would come to pass in the absence of price signals and corrections justifying it financially is, to be charitable, unclear.

Both Gates and Lomborg deserve plaudits for their disavowals: of cap-and-trade by Gates, of climate-change denialism by Lomborg; and for embracing the idea of a carbon tax. They now need to see the next light: to have the necessary impact, a carbon tax can start modestly but must keep rising predictably. Fortunately, we have the example of British Columbia to show that an upward-trending carbon tax of the needed size can be politically popular if the revenue is returned to the public.

(Some) Carbon Tax Advocates Are Serious

CTC rep James Handley’s comment on columnist Eric Pooley’s recent piece “Exxon Works Up New Recipe for Frying the Planet” (Bloomberg) sparked this illuminating, constructive exchange.

Dear Mr. Pooley,

Thanks for your article. Climate crisis deniers are indeed doing great harm. Are they really changing tactics from bogus science to bogus economics or just using both? I was with you until I read this:

“A tax wouldn’t guarantee any carbon reductions, let alone bring about the steep cuts needed to stave off the worst climate changes.”

If you’re suggesting that a cap would “guarantee” emissions reductions in some way that a tax would not, I must disagree.

Consider economist Alan Viard’s Aug. 4 testimony to the Senate Finance Committee:

If the market price of allowances under cap and trade is $20 per ton, every firm has an incentive to take any step that can reduce emissions at a cost of less than $20 per ton, but no incentive to take any step that reduces emissions at greater cost… precisely the incentive that each firm would face if it were subject to a carbon tax of $20 per ton or if it were subject to a cap-and-trade program (with the same $20 allowance price) in which all allowances were auctioned.

… The difference, of course, is that the carbon tax or the auction would raise government revenue equal to the aggregate value of the allowances. If the allowances are freely allocated, then that value instead accrues to firms. Cap and trade with free allocation is equivalent to a carbon tax with transfer payments to firms.” [Emphasis added.]

I work with the Carbon Tax Center because, along with most  economists who’ve considered the question, I’m convinced that a clear, transparent, gradually-increasing price on carbon pollution is essential to spur energy conservation as well as development and implementation of alternatives to fossil fuels. A carbon tax, with revenue recycled directly to households to build political support and mitigate the economic impacts of what portends to be a decades-long trek to a low carbon economy, offers a real “game changer” to move broadly enough to substantially mitigate climate catastrophe.

economists who’ve considered the question, I’m convinced that a clear, transparent, gradually-increasing price on carbon pollution is essential to spur energy conservation as well as development and implementation of alternatives to fossil fuels. A carbon tax, with revenue recycled directly to households to build political support and mitigate the economic impacts of what portends to be a decades-long trek to a low carbon economy, offers a real “game changer” to move broadly enough to substantially mitigate climate catastrophe.

British Columbia has shown that a revenue-neutral carbon tax can be implemented in a few months and gain public support. And it’s far more effective than trading in carbon allowances, especially with offsets. Price volatility has prevented the EU’s cap-and-trade from spurring investment in alternative energy and conservation. See e.g., EU Cap-and-Trade System Provides Cautionary Tale (Roll Call).

The enemy of my enemy isn’t necessarily my friend. Climate crisis deniers’ opposition to cap-and-trade doesn’t make it a good idea. And the “endorsement” of a carbon tax by (former?) deniers can obscure the fact that a growing environmental and social justice coalition is advocating a carbon tax with revenue-recycled to households. Please don’t help the “deniers” poison the water for the most effective, transparent climate policy.

– James Handley, Carbon Tax Center

———-

James,

Thank you for your very thoughtful note. A full treatment of the cap v. tax debate was beyond the scope of the column, but I didn’t mean to suggest that a well -designed tax would be unworkable, rather that any tax Exxon would support is likely to be ineffective.

My basic concern here is political rather than economic– that the carbon tax will siphon enough support to derail cap and trade, but not enough to pass, and we will be left with nothing. I tend to agree with Al Gore when he points out that the nations that have been most effective in reducing emissions have both a cap-and-trade program and a carbon tax in place; ultimately we are likely to need both as well, but that’s a ways off. In the meantime, as Gore has said, “a cap-and-trade system is also essential and actually offers a better prospect for a global agreement, in part because it is difficult to imagine a harmonized global CO2 tax.” The fact is, cap and trade is the only climate program that has a chance of passing now. There’s a big game going on inside the stadium, but the carbon tax proponents are outside in the parking lot, dreaming about next year.

I don’t think cap and trade is (as many tax proponents have argued) a faintly disreputable cousin to the tax which no one would welcome if the tax itself were passable now. I think the cap has real advantages, which I’ll get to. I understand the longing for a simpler approach to the problem but have my suspicions about the simplicity argument; a tax bill would have to respond to the same legitimate regional and sector cost issues that complicated Waxman-Markey, so a bill that could pass would not be simple. How for instance would the straight per capita tax rebate or payroll offset I often see proposed deal with the higher cost burden in coal-dependent states? Staffers on the Hill tell me that adjusting the tax every few years would require a new Act of Congress every few years — it’s hard enough to get this done once.

The free allowance formula devised by EEI and incorporated in Waxman-Markey, by taking into account carbon intensity, isn’t perfect but does a good job of responding to the regional disparity issue. And since the bill requires LDCs [local (electric) distribution companies] to pass on the value of all allowances to their ratepayers, it would prevent the LDCs from enjoying windfalls. Alan Viard’s testimony ignores this requirement when it claims that the value of free allowances accrues to firms. That’s not how the bill works—it’s one of many misconceptions about Waxman-Markey. Overall I’m impressed with the way Waxman et al. learned from the mistakes in the EU ETS. Over-allocation and lack of baseline data were the biggest drivers of volatility there, and this program would avoid those. Nor would utilities be able to charge opportunity costs to their ratepayers, as EU generators did. Giving the transitional allowances to LDCs instead of generators solves other problems as well. It sends a clean price signal to the generators while cushioning ratepayers.

As for the ‘guarantee,’ of course there is no magic wand. But the cap is more than a price signal. We do have the technology to monitor and verify reductions, and I want to see that framework put in place as soon as possible. Finally, no one seems to talk about the penalties for busting the cap, which under Waxman-Markey amount to 2x the allowance price plus a replacement allowance, or three times to compliance incentive — under your $20/ton comparison, the compliance incentive for the cap is actually $60 per allowance, vs. $20 for the tax, plus the strong market signal driven by the knowledge that the cap is ratcheting down over time. The aggressive 2030 reduction target in Waxman-Markey — 42% below 2005 levels —has not received the attention it deserves. It would transform the energy investment decisions of American businesses.

Thanks again for your email and for your work at the Carbon Tax Center. I really would welcome either a tax or a cap. But at the risk of turning your words against you, let me suggest, as someone who has been watching this debate unfold, that it is the carbon tax advocates who have at times been poisoning the water against the cap. Probably both sides have been guilty of this, but it’s too bad that the climate action community is divided at the very moment unity is so badly needed.

– Eric Pooley

———-

Eric,

Thanks for your reply. I think we’re in strong agreement on most points. I want to respond to three:

1) You wrote: “My basic concern here is political rather than economic– that the carbon tax will siphon enough support to derail cap and trade, but not enough to pass, and we will be left with nothing…”

Fortunately, it’s not ACESA or nothing. Although, given that ACESA’s attempted domestic emissions reductions are so modest, and that its cap-and-trade system would entrench Wall Street traders and purveyors of offsets and set the stage for another financial crisis, I’d probably opt for nothing.

If ACESA fails to pass, EPA can continue to develop a regulatory system under the Clean Air Act, which the Center for Biological Diversity has concluded could be quite comprehensive (and might include a cap-and-trade system). This is likely to be better than ACESA in several key ways. For instance, I gleaned from EPA’s Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking last year that its rule would not include offsets. (Can you imagine EPA trying to justify the up to 1.5 billion tons of international offsets — essentially, transfer payments — that make a mockery of the notion of a “hard cap” in ACESA?) Furthermore, ACESA as passed by the full House would eviscerate EPA’s proposal to account for indirect impacts of biofuels (e.g., forest clearing to grow corn for ethanol).

Because the Clean Air Act covers stationary sources, mobile sources and the content of fuels, the scope of an EPA GHG reduction program can be very broad. President Obama’s representatives could go to Copenhagen with an EPA draft rule in hand, pointing out that the U.S. is in the process of regulating (or “capping”) more of its GHG sources than any other industrialized nation. That’s far from the most effective policy (a revenue-neutral carbon tax) but it’s also a long way from “nothing.”

2) You quote Al Gore “…a cap-and-trade system is also essential and actually offers a better prospect for a global agreement, in part because it is difficult to imagine a harmonized global CO2 tax.”

Gore’s got it backwards. As the Congressional Budget’s report, “Policy Options for Reduction of CO2 Emissions,” explains, if nations choose different carbon tax rates (or fail to enact them) WTO authorizes border adjustments to equalize tax rates on imported products to the same levels applied to similar domestically-produced products. In effect, the U.S. would collect the carbon tax on imports from any country that didn’t enact its own, providing a powerful incentive for our trading partners to follow our lead.

In contrast, under cap-and-trade, harmonization would require determining the implicit carbon price in a system where carbon prices are hidden and fluctuating. The CBO observed, “Linking cap-and-trade programs would… entail additional challenges beyond those associated with harmonizing a tax on CO2.” The report noted, for example, that linked cap-and-trade programs tend to create perverse incentives for countries to choose less stringent caps so they could become net suppliers of low-cost allowances.

Moreover, as Elaine Kamarck of Harvard’s Kennedy School has pointed out, almost every nation has a tax collection mechanism that could be used to administer a carbon tax, but few (if any) have the means to enact and enforce a complex cap-and-trade system. If we’re going for a global carbon reduction system, it’s a carbon tax.

3) You wrote: “…a tax bill would have to respond to the same legitimate regional and sector cost issues that complicated Waxman-Markey, so a bill that could pass would not be simple… adjusting the tax every few years would require a new Act of Congress every few years — it’s hard enough to get this done once.”

The complexity (and length) of Waxman-Markey seems to have much more to do with preserving (and even expanding) the coal industry than with addressing regional disparities in household income caused by carbon pricing, which, in fact, are relatively small. (See our summary: Regional Disparities.)

Economist Dallas Burtraw (Resources for the Future) studied the regional “incidence” of carbon pricing and concluded that regional differences are dwarfed by very large disparities across the income spectrum. CTC’s proposed carbon tax shift would more than compensate for the inherent regressivity of a carbon tax by distributing revenue progressively either through a payroll tax cut (as proposed in legislation introduced by Rep. John Larson) or a direct, equal distribution. Waxman-Markey only attempts to compensate the lowest income group, leaving middle income households to shoulder the burden of carbon pricing. (Burtraw and others have also shown that ACESA’s free allowances to LDCs would mostly benefit commercial, not residential electricity users.)

We recognize that some regional adjustment might also be needed; but that’s a relatively simple proposition under a carbon tax and could be done administratively, without the need for legislation. Rep. Larson’s bill provides for automatic increases in the carbon tax level to ensure that the trajectory of emissions reductions is in line with the scientific consensus.

Thanks again,

James

———-

James,

I think you’re kidding yourself about the EPA’s ability to impose cap-and-trade under CAA. Someone who knows a lot more about politics than either of us, former White House Chief of Staff John Podesta, has said it would be difficult for EPA to do so without Congressional assistance. Protracted litigation would see to it that years went by before such a system came into force. And there is no chance that an administration promise of such rulemaking – which any subsequent administration could undo – could form the basis of a treaty.

Dallas Burtraw is a fine economist, but the many Senators and members of Congress I have been talking to all summer simply do not agree with him. Regional and sectoral disparities are the single biggest obstacle to climate action, and lawmakers do not believe that the “simple carbon tax” solves them. That’s why Rep. Mike Doyle of Pennsylvania backed Waxman-Markey instead of John Larson’s carbon tax. It’s one of the reasons Waxman-Markey passed the House and Larson’s bill didn’t make it to markup. If the politics were reversed and a carbon tax had a shot at passing, I would expect cap-and-traders to get behind the carbon tax and push hard. But right now, it is the cap that has a real chance of passage, and it could be years before the next opportunity presents itself. Please don’t let your strong shoulders go to waste.

– Eric

———-

Eric,

Regional and income disparities arise under either a carbon tax or cap-and-trade (in fact, Burtraw considered it the same problem), but it’s easier to mitigate these regional and income disparities under a transparent carbon tax by directly distributing the revenues to households.

Rep. Larson and the other members of the Ways and Means Committee, which held a series of very illuminating hearings last spring about the very serious volatility and gaming with cap-and-trade, didn’t get a shot at climate legislation because the House leadership didn’t permit amendments – they didn’t want any discussion of alternatives to cap-and-trade.

I agree with economist Robert Shapiro (Clinton undersecretary of Commerce and U.S. Climate Task Force co-chair) who said at our July 13 Senate briefing that ACESA deserves to be defeated. He fears that, as in the E.U., cap-and-trade would fail to reduce emissions and would delay needed reductions by a decade or more. I cannot support a hidden, volatile and regressive carbon tax (set and collected by Wall Street) whose main advantages seem to be that it hides the price and is called “cap-and-trade”. I believe an explicit, predictable and progressive carbon tax with revenue recycled to households is essential. British Columbia’s experience shows that a revenue-neutral carbon tax is politically feasible. But, to return to my original point, first we need to get beyond magical thinking about “caps”.

– James

photo: Flickr / random dude

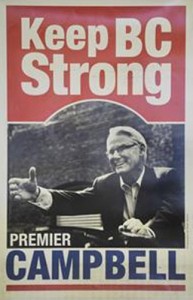

BC Voters Stand By Carbon Tax

Climate campaigners across North America awoke this morning and smelled the coffee: a resounding electoral victory in British Columbia.

Voters in Canada’s third-largest province yesterday returned to power, for a third four-year term, BC premier Gordon Campbell and his Liberal Party, who last July instituted the Western Hemisphere’s first major carbon tax.

We’ll let AFP news service report for us (emphases added):

British Columbia re-elects Liberals (May 13)

VANCOUVER, Canada (AFP) — Voters in Canada’s westernmost province kept a controversial carbon tax by re-electing the provincial government and rejected a landmark referendum for proportional representation.

As the British Columbia elections agency reported more than 60 percent of votes had been counted, the pro-business Liberals held a strong lead, with nearly 46 percent of votes compared to slightly more than 42 percent for the left-wing opposition New Democratic Party.

Two hours after the polls closed, New Democratic leader Carole James conceded defeat…

The Liberals and New Democrats, the province’s two main parties, had sparred during the campaign over issues including the economy, homelessness and several local scandals. But the environment — and especially the carbon tax — became the key election issue.

The tax, the first straight carbon tax in North America, was introduced by the government of British Columbia Premier Gordon Campbell in 2007 [ed. note: 2008] to help fight climate change. The tax is revenue neutral — the collected tax money is paid once a year to provincial residents.

The New Democrats, led by Carol James, fiercely opposed the carbon tax, arguing that it especially hurt rural residents. But the party’s opposition to the tax cost them the support of almost all environmental organizations, which sided with Campbell solely on the issue, while the nonpartisan Conservation Council launched a campaign telling voters to choose “anybody but James.”

The Green Party, which garnered slightly more than eight percent of total votes in early results, supported the carbon tax. But Green Party leader Jane Sterk was defeated in her home riding on Vancouver Island.

The election win gave Campbell a third term — a rare occurrence in the province — with his party holding a majority of British Columbia’s 85 legislature seats.

While elections are not referenda, the AFP report makes clear that the carbon tax stood front and center in the BC voting. After scanning hundreds of articles on the two-month campaign (and being interviewed for a handful, as well as appearing on Vancouver radio), our reading is that voters rewarded the Liberals for sticking to principle and standing up to the NDP’s withering attacks, as much as for the substance of the carbon tax itself.

The BC carbon tax took effect on July 1, 2008 at a rate of $10 (Canadian) per metric ton of carbon dioxide. Converting currencies and metrics, it equates to a very modest $7.80 per ton of CO2. However, the tax is to rise each year through 2012 by half the original amount, reaching the U.S. equivalent of around $11.75/ton this July 1 and, in 2012, around $23.50.

A U.S. carbon tax at that level would raise petrol prices by approximately 23 cents a gallon and national-average electricity prices by around 1.7 cents a kilowatt-hour. (Virtually all power generation in British Columbia is hydro-electric, so the carbon tax effectively exempts electricity.)

The BC tax is revenue-neutral, with revenues returned to taxpayers through personal income and business income tax cuts. The Feb. 19, 2008 BC Budget and Fiscal Plan spells out the tax’s rationale, impacts and mechanics, and is essential reading for any carbon tax advocate seeking to master communication tools for making a carbon tax palatable to the public.

In an e-mail to the Carbon Tax Center yesterday, American climatologist and climate campaigner James Hansen said, “The important thing is to get on the right policy track at the beginning — the policy must attack the fundamental problem, that dirty fossil fuels are the cheapest energy because they are not made to pay their costs to society.” Yes, carbon taxes must eventually reach high levels, but what matters now is that one major jurisdiction has gotten on the right policy track.

U.S. climate campaigners, mired in cap-and-trade murk, could learn from yesterdays’ election. At the very least, we owe a big debt of gratitude to BC Premier Gordon Campbell and his Liberal Party for political courage, and likewise to the voters of British Columbia for rewarding that bravery in the voting booth.

Photo: Flickr / Skagit IMS

Imagine: A Harmonized, Global CO2 Tax

“For more than 20 years, I have supported a CO2 tax, offset by an equal reduction in taxes elsewhere. However, a cap-and-trade system is also essential and actually offers a better prospect for a global agreement, in part because it is difficult to imagine a harmonized global CO2 tax. Moreover, I have long recognized that our political system has special difficulty in considering a CO2 tax even if it is revenue neutral.” — Al Gore, quoted in New York Times, House Bill for a Carbon Tax to Cut Emissions Faces a Steep Climb, March 7.

Let’s examine Mr. Gore’s points:

Harmonization: Mr. Gore has raised a crucial concern: Any carbon-reduction policies the U.S. enacts must quickly go global. Acting alone or counter to other nations’ efforts will not suffice.

In their seminal report last February, “Policy Options for Reduction of CO2 Emissions,” Peter Orszag (now Budget Director) and Terry Dinan of the Congressional Budget Office meticulously compared cap-and-trade with carbon tax options. They concluded that a carbon tax would reduce emissions five times more efficiently, primarily because of price volatility under a fixed cap.

In their seminal report last February, “Policy Options for Reduction of CO2 Emissions,” Peter Orszag (now Budget Director) and Terry Dinan of the Congressional Budget Office meticulously compared cap-and-trade with carbon tax options. They concluded that a carbon tax would reduce emissions five times more efficiently, primarily because of price volatility under a fixed cap.

CBO had no difficulty “imagining a harmonized global carbon tax.” Chapter 3 of the Orszag-Dinan report, “International Consistency Considerations,” describes straightforward ways to harmonize carbon taxes. If nations choose different carbon tax rates, border tax adjustments permitted under World Trade Organization rules authorize higher-taxing nations to enact tariffs to equalize tax rates on imported products to the same levels applied to similar domestically-produced products.

Indeed, Rep. John Larson’s new carbon tax bill employs precisely this strategy. In effect, the U.S. would collect and retain the revenue generated by equalizing carbon taxes on products imported from countries that haven’t enacted their own or whose carbon tax rate is lower than ours. That will provide a powerful incentive for our trading partners to follow our lead.

In contrast, under cap-and-trade, harmonization would require determining the implicit carbon price in a system where carbon prices are hidden and fluctuating. The CBO report observed, “Linking cap-and-trade programs would… entail additional challenges beyond those associated with harmonizing a tax on CO2.” The report noted, for example, that linked cap-and-trade programs could create perverse incentives for countries to choose less stringent caps so they could become net suppliers of low-cost allowances.

Or, the report continued, if a country that did not allow borrowing future allowances linked with a country that did, firms in both countries would have access to borrowed allowances. CBO concluded that “[O]ther flexible design features — such as banking, offsets, and a safety valve — would be available to all firms in a linked system should any one country allow its firms to comply in those ways.”

In short, national cap-and-trade systems would be nearly impossible to harmonize globally because different countries are likely to enact cap-and-trade systems with differing features that when linked would tend to defeat or de-stabilize each other. On the other hand, harmonization of domestic carbon taxes using border adjustments is a familiar and straightforward process for international trade and tax law experts under WTO.

Political Feasiblity: Gore also lamented that “our political system has special difficulty considering a carbon tax even if it is revenue neutral.” He has a point. After decades of anti-tax propaganda from the likes of Grover Norquist, Congress is understandably inclined to hide carbon pricing under a name like “cap-and-trade.” But when that first cap-and-trade price spike hits a public that was sold cap-and-trade as the un-tax, won’t its superficial naming advantage evaporate like morning dew? Will “cap-and-trade” still sound better than “revenue-neutral carbon tax” when we’re stuck with a slow, complex, costly and ineffective system?

Moreover, unlike cap-and-trade, a national carbon tax is showing signs of bipartisan support. One reason is that a carbon tax dispenses with the protracted drafting and wrangling inherent in cap-and-trade. British Columbia implemented its carbon tax in five months.

Cap-and-trade is “also essential”: Perhaps to newly-unemployed derivatives traders. But not for the rest of us. The Larson bill assures specific emissions reductions (as surely as with any other system) without the inherent problems of trading carbon derivatives. The bill automatically bumps up the carbon tax rate if emissions stray from an EPA-certified path to cut emissions by 80% from 2005 levels in 2050.

Yes, we can imagine, and yes, we must enact, a harmonized global carbon tax system. Al Gore and Jim Hansen persistently warn us: curbing the menace of uncontrolled climate change requires aggressive world-wide incentives to usher in efficiency and renewables. Price transparency and incentives for other nations to enact carbon taxes are crucial.

Rep. Larson has defied the naysayers; he has put the “t” word back on the table. Not a moment too soon.

Photo: Flickr / pbo31

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- Next Page »