U.S. progressive activists have turned away from carbon pricing. Some are opposed, some are indifferent but few, it seems, vocally support carbon taxing or other ways to price carbon emissions.

To be sure, we have no data tracking left-progressives’ attitudes toward pursuing carbon taxes as part of a climate policy agenda. Still, it’s safe to say that support for carbon taxes by prominent progressive-identifying leaders and organizations is far less common today than it was early on in Barack Obama’s presidency, when a Democratic carbon cap-and-trade bill passed the House but failed in the Senate.

A case in point is Are We Entering a New Political Era?, a May 31, 2021 New Yorker magazine profile of the insurgent group Justice Democrats who were reported to be “reshaping the Democratic Party by giving moderates an unignorable reason to guard their left flank.” The article plumbed the politics of the climate crisis and the Green New Deal without once mentioning carbon taxing — a clear sign that the idea of pricing carbon emissions has fallen off progressives’ political map.

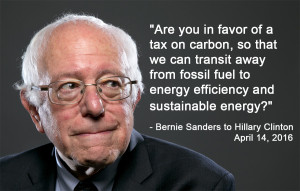

Bernie Sanders’ unabashed support for carbon taxing in his 2016 campaign has little resonance in today’s left.

(Curiously, the article mischaracterized Bernie Sanders’ 2016 climate plan as relying on “tax cuts and other market-based incentives.” Sanders’ climate platform actually centered on an aggressive carbon tax, not tax cuts, and we don’t recall his ever characterizing carbon taxing as market-based — a label we consider shallow and reductionist.)

Here, after a quick look back at the watershed 2016 carbon tax referendum in Washington state, we assess political progressives’ stances toward carbon pricing during the Biden presidency. This page can be viewed as a companion to our Carbon Pricing and Environmental Justice page.

We say “stances” (plural) because there’s a range of views on carbon pricing among political progressives. Still, mirroring changing currents among environmental justice advocates, politically active left-progressives in recent years have distanced themselves from carbon tax advocacy. Considering the U.S. right wing’s descent into near-monolithic climate denialism (summarized on our Conservatives page), the antipathy to carbon pricing on the left is helping to relegate full-throated support for pricing carbon emissions to an ever-narrowing political center.

The divisive 2016 battle over Washington state’s carbon tax referendum

The 2016 referendum to enact a carbon tax in Washington state was a political watershed for carbon pricing. Bypassing a coalition of environmental-justice advocates and other progressives, the bipartisan group Carbon Washington placed a revenue-neutral carbon tax on the ballot. Initiative-732 would have levied a statewide $20 per ton carbon emissions fee. Rather than investing in low-carbon infrastructure and frontline communities, the proceeds would have been applied to cutting the state sales tax, the nation’s highest, by a percentage point — a move intended to shield lower- and middle-income households from the financial burden of higher fuel prices from the carbon tax.

Progressive heavyweights Mary Kay Henry, Naomi Klein and Van Jones slammed Washington state’s 2016 carbon tax initiative. Criticisms of carbon taxing from the left have only intensified since.

The statewide coalition of progressives objected not only to this “revenue-neutral” form of carbon taxing but also to having their slower, consensus-building methodology trampled by upstarts aiming to touch off a nationwide prairie fire of state carbon taxes leading to a national carbon price. Progressive-identifying state organizations, augmented by prominent national figures like Service Employees International Union chief Mary Kay Henry, media darling Van Jones, and globe-trotting author Naomi Klein, lined up against the measure while most environmental groups remained neutral. I-732 lost resoundingly, and since then the divide in the climate ranks between carbon tax acolytes and left-leaning forces has only deepened. (The story is recounted on our page, Washington’s 2016 carbon-tax defeat.)

Ten reasons progressives have soured on carbon pricing

The schism over Washington’s I-732 didn’t emerge in a vacuum. Skepticism about carbon pricing — and pricing mechanisms generally — has long been present among people who lean progressive. We’ve collected and summarized ten reasons (they’re numbered for later reference):

- Sympathy for the idea that carbon pricing commodifies the natural world and demeans humans’ right to a safe environment and climate.

- The belief that pricing carbon emissions lets the affluent buy their way out of pollution regulations intended to protect vulnerable populations as well as the larger environment.

- Suspicion that carbon pricing is a quintessential neoliberal policy, and thus a handmaiden to austerity policies that elevate private enterprise and well-being above public governance.

- The oil industry’s ostensible support, which some regard as a badge of dishonor or Trojan Horse, or both.

- A preference for taxing billionaires’ and multimillionaires’ wealth rather than for broadly based carbon taxes that ensnare poor people as well as rich.

- Disdain for “market-oriented” measures as ploys to gain support from Republican voters and legislators.

- Belief that energy use is essential down to the last drop, which would make pricing mechanisms punitive rather than curative.

- Skepticism of the idea — a tenet of economics — that prices are a powerful determinant of human behaviors and choices.

- A preference for “carrots,” i.e., subsidies that lower sticker prices of alternatives to fossil fuels, versus the “stick” of making fossil fuels cost more.

- The conviction that society must be remade from the ground up through expansive public investment rather than through more diffuse programs with a top-down appearance.

These objections were always lurking. Nevertheless, in the past most progressives were willing to swallow them in the interest of gaining climate progress through eliminating fossil fuels’ artificial price advantage over efficiency and renewables. That changed with the 2016 Washington state schism, the rising opposition to carbon pricing by environmental advocates of color, and the sense of siege that settled in among progressives after the election of Trump — a cataclysm that appeared to require more fundamental responses than merely “tinkering with prices.”

These objections were always lurking. Nevertheless, in the past most progressives were willing to swallow them in the interest of gaining climate progress through eliminating fossil fuels’ artificial price advantage over efficiency and renewables. That changed with the 2016 Washington state schism, the rising opposition to carbon pricing by environmental advocates of color, and the sense of siege that settled in among progressives after the election of Trump — a cataclysm that appeared to require more fundamental responses than merely “tinkering with prices.”

In some ways, the changed mood comes down to the incongruity of seemingly politically-neutral calls to price carbon alongside the progressive mantra that “another world is possible.” Not many peoples’ idea of utopia includes triple-digit carbon taxes. (Though it’s also true that utopia doesn’t go well with a broken climate.)

Rebuttals

To carbon-tax proponents, all ten concerns are rebuttable:

- Better to commodify nature than leave it prey to ever-greater assault by failing to exact a price for damaging it.

- Similarly, making the affluent pay to pollute is preferable to letting them keep polluting for free.

- Rather than being a detriment, carbon pricing’s ostensible neutrality makes it a perfect complement — administratively as well as politically — to progressives’ desired regulations, standards and investments.

- Exxon and BP’s occasional professions of support for token carbon taxes are an obvious feint to advocates’ pushes for “robust” (triple-digit) carbon tax levels and should be treated as such.

- Nothing precludes taxing billionaires and also taxing carbon emissions; that’s CTC’s preferred policy suite, in fact, as noted here and here.

- Unlike cap-and-trade programs that entail markets in emission permits, carbon taxes are not “market mechanisms” — a canard that should be retired.

- Changing energy usage overnight can be difficult, even sacrificial; but over the longer time frames that matter for climate, energy use is surprisingly elastic (fuller discussion here).

- Prices influence the vast majority of the billions of short- and long-term daily decisions that collectively determine usage levels of fossil fuels and, hence, carbon emissions.

- Raising prices of “bads” reduces their use considerably more than does lowering the prices of the multitude of possible alternatives. (See CTC’s 2014 congressional testimony quantifying the longer reach of carbon taxes vis-a-vis subsidies for low-carbon fuels and technologies: pdf.)

- As noted in #3, carbon taxing is perfectly compatible with public investment and community participation; if it helps, think of carbon taxes as a tailwind to everything we want.

Admittedly, rejoinders don’t assuage the aversion to carbon pricing — even “pure” carbon taxing, untainted by offsets or other carve-outs — felt by most vocal progressives. To some on the left, carbon pricing presents as a piecemeal, reductionist, soulless approach that fails today’s “intersectional” moment. It’s not that pricing carbon won’t cut emissions (though we suspect that most progressives don’t fully grasp its reach — see points 7 and 8), but that, for many progressives, carbon pricing feels desiccated, dated and inadequate to the demand that everything wrong in the world be confronted at once.

Critiques of carbon pricing from a Spring, 2021 podcast about it

The Pricing Nature podcast gave voice to several prominent progressive climate activists in a May, 2021 episode, Carbon Pricing Hits a Brick Wall on the Left. We’ve tagged these excerpts from the podcast’s Substack page with our bullet points they match with:

Keya Chatterjee (then-executive director, US Climate Action Network): There’s simply a philosophical opposition —particularly in many indigenous cultures — there’s a philosophical opposition to the idea that you can give money to pollute. You can give money and continue to do something wrong as long as you pay to do that thing. (Reasons #1 & #2)

Michael Méndez (assistant professor, U-C Irvine): Initially, maybe 10 or 15 years ago, a majority of California environmental justice groups were advocating for carbon pricing. While it’s still a market-based solution or a neoliberal solution, it more closely aligned to their goals of having more stringent reductions in polluting facilities near the communities that they were living in. Over the time that evolution has changed a little and environmental justice groups have grown and have more influence in state legislatures and city halls, and to some extent at the federal government, where they’re advocating against all types of market-based mechanisms or neoliberal solutions. (#3, #6)

Keya Chatterjee, David Roberts and Michael Méndez aired their concerns about carbon pricing on a “Pricing Nature” podcast.

What’s striking about those statements is their abstract quality. Philosophical opposition . . . market-based mechanisms . . . neoliberal solutions. Nothing about whether and how fast carbon taxes might actually cut carbon emissions, reduce co-pollutant emissions in fenceline communities, and make poor and working-class families better off financially.

Keya Chatterjee: We have massive income inequality in this country. We have massive racial injustice. We have a huge wealth gap between black and white people in this country, a massive wealth gap. There is nothing that we should be doing that puts any additional burden on people who have less. It should be quite the opposite. If we need to pay to deal with the climate crisis, that money should come from the people who created the climate crisis, the polluters. If we need more money, it can come from a wealth tax. (#5, #7)

David Roberts (author of the Volts newsletter): I think they [Green New Deal proponents] realized there just aren’t enough environmentalists to do something this big. Like we’re talking about remaking the entire economy. We’re talking about revolutionizing the entire direction of the world, you know? And that’s not something that the “environmental movement” has the juice to do. If we want to do that, we have to build a coalition. We have to bring everybody together. (#4, #8, #9, #10)

Unacknowledged in Chatterjee’s quotes in the Substack page is that with the right carbon tax, such as Citizens Climate Lobby’s fee-and-dividend, the dividend puts more money back in most poor and working households’ pockets than the fee takes away through costlier fossil fuels. She’s right, of course, about systemic economic inequality and massive wealth gaps — a matter so central to our dysfunctional politics and society that our site has an entire page about it. And as we’ve written repeatedly, as in this 2019 post, A New Synthesis: Carbon Taxing, Wealth Taxing & A Green New Deal, we’re in complete synch with her in wanting wealth taxes to pay for the Green New Deal.

Chatterjee almost certainly is conversant with the various carbon dividend proposals. Could it be that, like some other progressives, she believes in her heart that carbon tax revenues should be spent on carbon-reduction programs (rehabbing leaky houses, boosting public transportation, and so forth) and thus opposes distributing the revenues as dividends to households? Perhaps she lacks conviction that making coal, oil and gas cost more will actually move the needle on decarbonization?

We suspect it’s the latter. For evidence there’s Chatterjee’s phrase, “If we need to pay to deal with the climate crisis,” suggesting that, like many progressive activists, she views carbon taxes only as pay-for’s to finance green infrastructure and overlooks their other dimension: inducing across-the-board changes in behavior and investment.

Then there’s climate-politics commentator David Roberts, contending that the imperative of constructing a big-tent climate movement overrides the potential payoffs from carbon taxes — a thesis he trenchantly articulated in his May 2020 Vox post, At last, a climate policy platform that can unite the left.

Then there’s climate-politics commentator David Roberts, contending that the imperative of constructing a big-tent climate movement overrides the potential payoffs from carbon taxes — a thesis he trenchantly articulated in his May 2020 Vox post, At last, a climate policy platform that can unite the left.

“For the first time in memory,” Roberts wrote then, “there’s a broad alignment forming around a climate policy platform that is both ambitious enough to address the [climate] problem and politically potent enough to unite all the left’s various interest groups.” The platform, which Roberts and others dubbed S-I-J (Standards-Investment-Justice), pointedly omitted carbon pricing:

Carbon pricing — long treated as the sine qua non of serious climate policy — is no longer at the center of these discussions, or even particularly privileged in them. For one thing, there’s the political economy: Raising prices is unpopular, and raising prices enough, fast enough, to hit the 2050 target will be an almost insuperable political challenge. Cap and trade is still in the reputational toilet. Carbon taxes never saw the bipartisan support their backers always promised. The politics of carbon pricing just don’t seem to be going anywhere. (emphasis added)

There, at last, is an objection to carbon pricing that registers. Indeed, we share enough of it to have declared, three months into the Biden administration, that we did not want the president or Congressional Democrats to seek carbon tax legislation at least until after the 2022 midterms, on grounds that it can’t pass until the Democrats have more than paper-thin majorities. We also expressed strong support for the climate provisions of the Biden-Schumer Inflation Reduction Act, even though they embody the diametrically opposite approach from carbon pricing: making clean energy cheap rather than making dirty energy more expensive.

We differ from Roberts, however, in hoping that larger Congressional margins will embolden Biden to push for a carbon tax if and when Democrats have firm control of Congress . As much as we admire Roberts’ perspicacity, we’re not sure he has ever tuned in fully to carbon taxers’ key argument: pricing carbon emissions will go a long way to curtailing and eliminating fossil fuels, while not pricing them almost certainly consigns climate efforts to falling short. We also note the circularity implicit in Roberts’ last sentence excerpted above: since carbon pricing isn’t going anywhere, let’s set it aside, which ensures it won’t go anywhere.

Like Roberts and other progressives, we believe another world is possible, but we also believe carbon pricing is a key to building it.

CTC’s Carbon-Tax Strategy

Following, from mid-2021, was our rough schema for the remainder of 2021 and all of 2022:

- Biden and Congressional Democrats enact uncontroversial wind, solar and electric vehicle incentives and programs as part of an infrastructure package.

- By establishing and showcasing alternatives to fossil fuels, these measures soften opposition to carbon pricing somewhat.

- Along with vehicle and appliance efficiency standards, these initiatives cut carbon emissions, albeit not massively (due to both lead times and the fact that neither renewables nor standards attack fossil fuel use holistically).

- The stubbornness of U.S. carbon emissions increases belief in the necessity of carbon pricing to achieve deep cuts.

- The Biden administration aggressively addresses disparate pollution incidence and other environmental injustices through such initiatives as its proposed $20 billion plan to reconnect predominantly Black neighborhoods severed by highways in mid-20th Century “slum clearance,” winning greater trust among EJ advocates.

- Biden and Congressional Democrats raise taxes on wealthy businesses and households, mollifying progressives and making inroads into Republicans’ “populist” base.

- These and other popular and successful programs enable Congressional Democrats to expand their majorities in the Nov. 2022 midterms.

“That’s a tough needle to thread,” we wrote then, adding that “we believe it’s achievable and can lay the groundwork for enacting a meaningful carbon tax in 2023-2024.”

Conversely, though conditions can always change, right now we don’t see other paths to the kind of robust carbon pricing that can slash U.S. emissions and establish a template for concerted global climate action.