British Columbia, Canada’s third-most populous province, began taxing carbon dioxide and other greenhouse-gas emissions from combustion of fossil fuels nearly seven and a half years ago, pursuant to the province’s Carbon Tax Act. The province-wide tax commenced on July 1, 2008 at a level of $10 (Canadian) per metric ton (“tonne”) of CO2 and increased by $5 per tonne in each of the next four years, reaching its current level, $30/tonne, in July 2012.

The point of the tax is to reduce emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. It is therefore surprising that very little detailed quantitative analysis of the tax’s efficacy in reducing emissions has appeared to date. Answers haven’t been readily available to fundamental questions such as: Have British Columbia emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas actually fallen? If they have, by how much? How have the reductions in BC emissions stacked up against the rest of Canada, which does not tax carbon emissions (save for modest taxes in Alberta and Quebec)? How does the recent trajectory of British Columbia emissions compare to that prior to the onset of the tax? Which sectors have shown the biggest, or the smallest, declines?

The Carbon Tax Center searched for answers to these questions during 2015. Not finding definitive data, we set out to develop our own. The result is a new report, British Columbia’s Carbon Tax: By the Numbers, which available here. A spreadsheet with supporting data is available here.

BC’s carbon tax is both the most comprehensive and transparent carbon tax in the Western Hemisphere, if not the world. A recent assessment by two leading environmental economists stated that “British Columbia has given the world perhaps the closest example of an economist’s textbook prescription for the use of a carbon tax to reduce [greenhouse gas] emissions.”

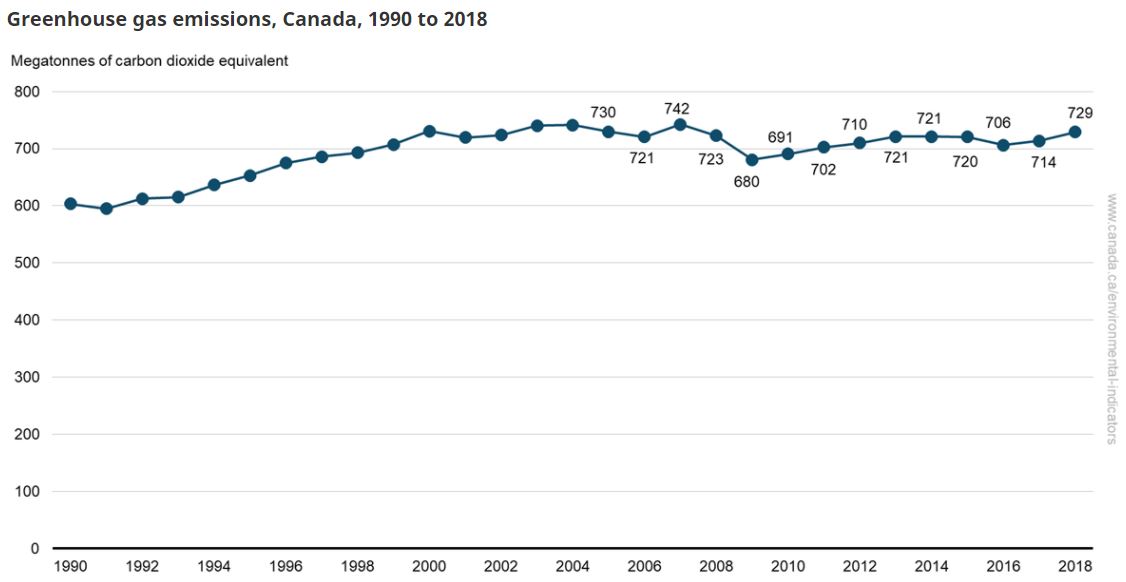

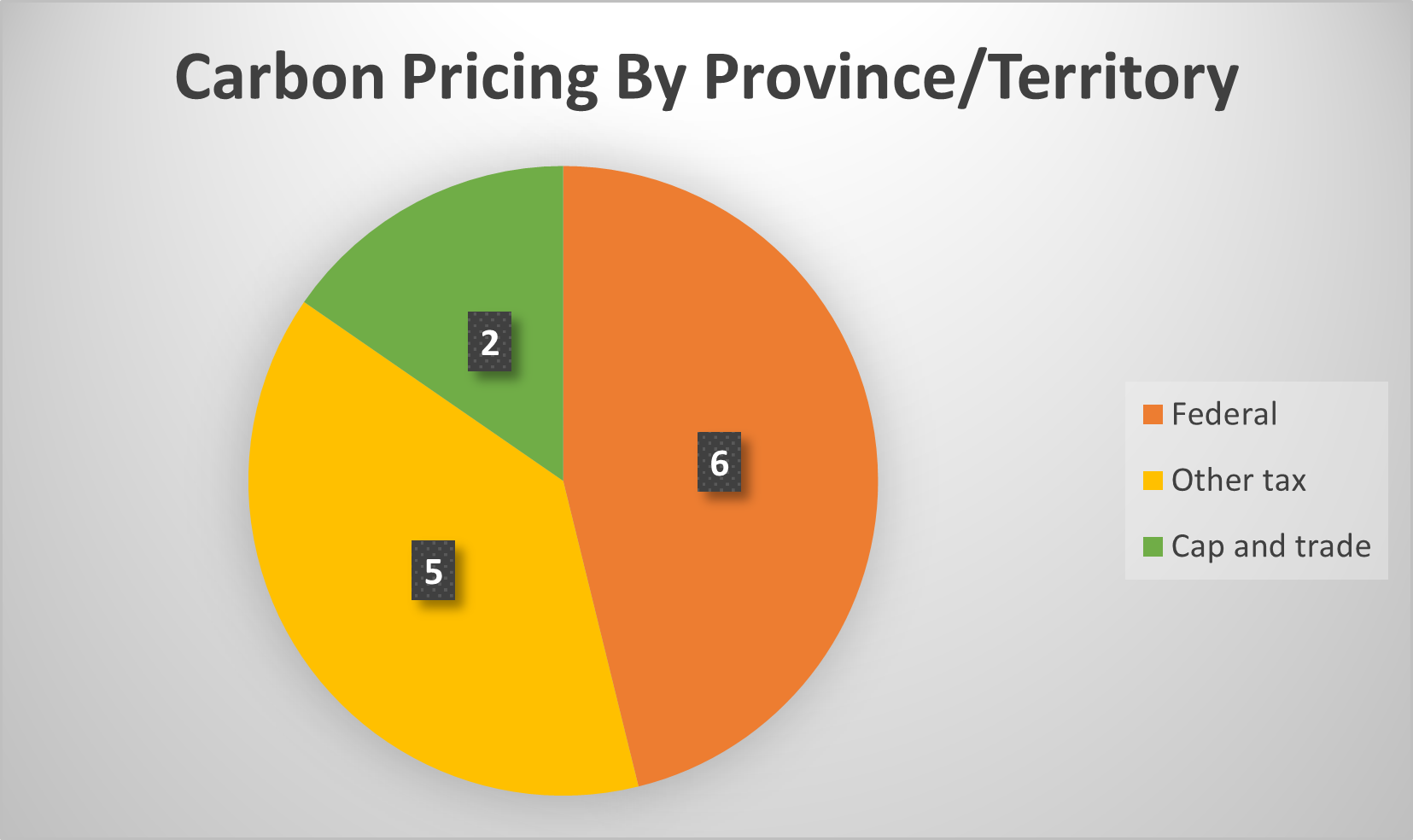

Moreover, the BC tax is gaining adherents. On the eve of the Paris climate summit, in November 2015, Alberta Premier Rachel Notley committed to a similar carbon tax. Alberta’s tax will begin in 2017 at $20 per metric ton and rise in 2018 to $30, matching the current level in British Columbia. Although Canada’s two most populous provinces, Ontario and Quebec, are moving toward carbon cap-and-trade systems, the new Trudeau administration in Ottawa could choose to fashion a national carbon tax from British Columbia’s, with the possibility of higher tax levels to evoke larger emission reductions.

Executive Summary and Key Findings

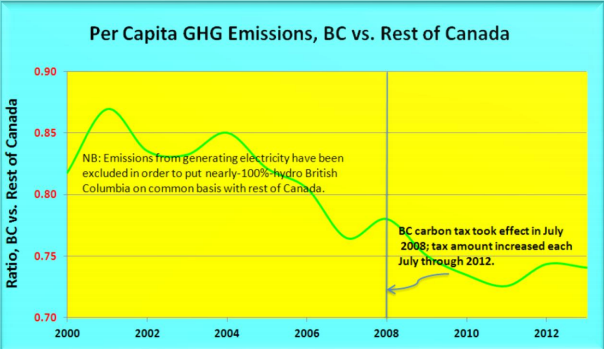

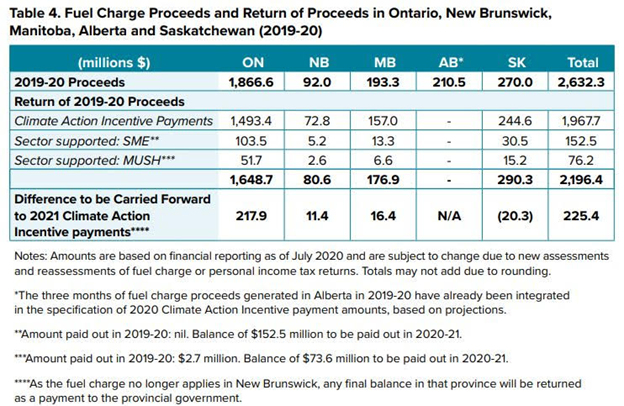

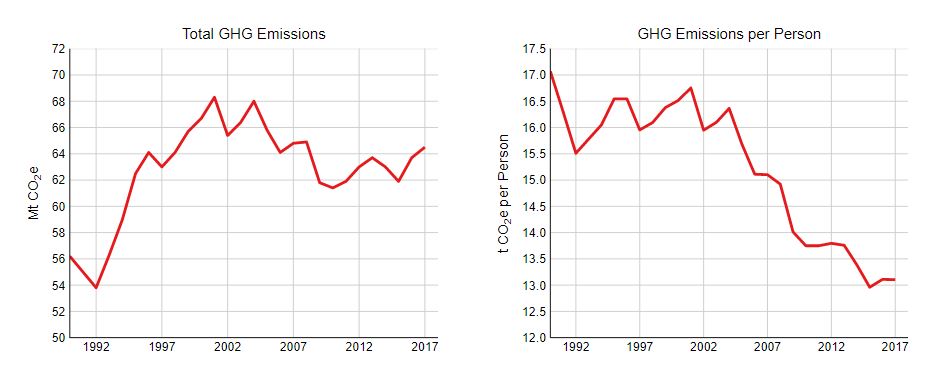

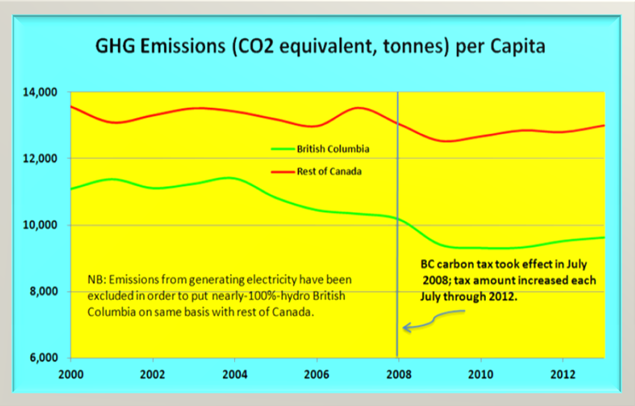

British Columbia introduced a carbon tax in 2008. Since then, per capita emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases covered by the tax have declined, continuing a downward trend that began in 2004. Averaged across the period with the tax (2008 through 2013; no data are available for 2014), province-wide per capita emissions from fossil fuel combustion covered by the tax were nearly 13 percent below the average in the pre-tax period under examination (2000-2007).

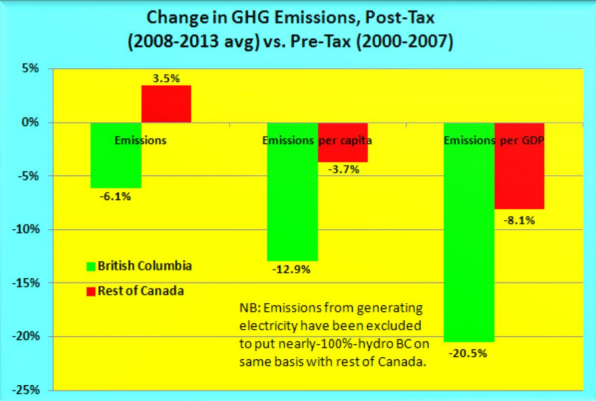

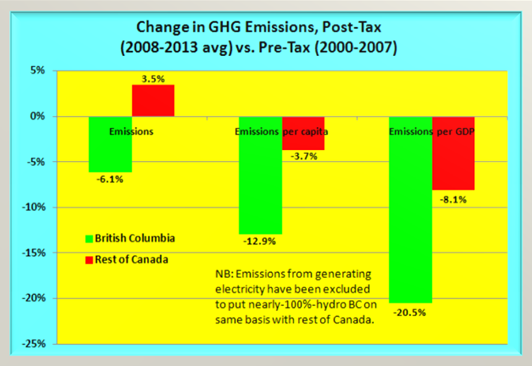

The 12.9% decrease in British Columbia’s per capita emissions in 2008-2013 compared to 2000-2007 was three-and-a-half times as pronounced as the 3.7% per capita decline for the rest of Canada. This suggests that the carbon tax caused emissions in the province to be appreciably less than they would have been, without the carbon tax.

To allow comparability, the above figures are per capita. They also exclude emissions from electricity production ― a minor emissions category for British Columbia, which draws most of its electricity from abundant (and zero-carbon) hydro-electricity, but a major emissions source for much of Canada. On a total emissions basis (not per capita), British Columbia emissions of CO2 and other GHGs covered by the carbon tax but excluding the electricity sector averaged 6.1% less in 2008-2013 than in 2000-2007. (The reduction was 6.7% when electricity emissions are counted.) The 6.1% contraction is roughly what would be expected from a small carbon tax such as British Columbia’s. (See sidebar on page 5.)

The carbon tax does not appear to have impeded overall economic activity in British Columbia. Although GDP in British Columbia grew more slowly during 2008-2013, the period with the carbon tax, than in 2000-2007, the same was true for the rest of Canada. From 2008 to 2013, GDP growth in British Columbia slightly outpaced growth in the rest of the country, with a compound annual average of 1.55% per year in British Columbia, vs. 1.48% outside of the province.

GHG emissions increased in British Columbia in 2012 and again in 2013, not just in absolute terms but also per capita. This suggests that the carbon tax needs to resume its annual increments (the last increase was in 2012; its bite has since been eroded by inflation) if emissions are to begin again their downward track.

Click here to read the full report.